E201Lectures - Central Web Server 2

advertisement

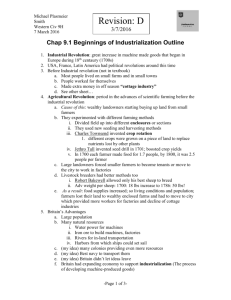

Economics 201 European Economic History Fall 2004 MWF 9-9:50 Castleman 212 R. N. Langlois Richard.Langlois@UConn.edu http://langlois.uconn.edu Office: Room 322 Monteith Office hours: MWF 10:15-12 or by appointment 1 Books and readings. Rondo Cameron and Larry Neal, A Concise Economic History of the World. New York: Oxford, 2003. Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel. New York: Norton, 1997. Douglass C. North, Structure and Change in Economic History. New York: Norton, 1981. Nathan Rosenberg and L. E. Birdzell, Jr., How the West Grew Rich. New York: Basic Books, 1986. Frances and Joseph Gies, Life in a Medieval Village. New York: Harper, 1990. . 2 Course requirements. Midterm 1 30% Midterm 2 30% Final 40% 3 Points to remember. Come to class. Check online syllabus regularly for new links and materials. 4 Central Question: Why Europe? 5 Economic growth. Extensive growth. Total income (Y) increases. Intensive growth. Per capita income (Y/N) increases. Example: India versus Australia. 6 Intensive economic growth. Australia (1998) India GDP US$ 382,335 million* US$ 1,702,712 million* Pop. 18.75 million 975 million Y/N US$ 20,391 US$ 1,746 *1990 international $ 7 Income per capita 1999. United States $30,600 Japan $24,041 Australia $22,448 United Kingdom $20,883 Spain $16,730 Argentina $11,324 Russia $6,339 China $3,291 India $2,149 Tanzania $478 GNP per capita, 1999 international dollars, PPP method. Source: The World Bank. 8 Economic growth. $40,000 $35,000 $30,000 $25,000 $20,000 $15,000 $10,000 $5,000 1999 1989 1979 1969 1959 1949 1939 1929 1919 1909 1899 1889 1879 1869 1859 1849 1839 1829 1819 1809 1799 1789 $0 Growth in U. S. GDP per capita, 1789-2001 (1996 dollars). Source: Johnston and Williamson (2002) 9 What is economic growth? Adam Smith (1723-1790). Author of the Wealth of Nations (1776). Picture courtesy of the Warren J. Samuels Portrait Collection at Duke University. Mercantilists: wealth is an excess of money or real goods. Adam Smith: wealth is not stuff; wealth is productivity. Productivity is total output divided by total input: Y/L. Smith: the ability to command resources with labor time. 10 Declining time-price of food. 3-lb. Fryer: 1919: 3.5 hours. 1997: 27 minutes. 11 Falling death rates. 45 40 35 30 25 US 20 GB 15 10 5 0 1700 1850 1910 1980 Annual deaths per thousand, United States and Great Britain. Source: Fogel (1986), p. 44, Table 9.1. 12 Increasing life expectancy. 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 U. S. life expectancy at birth in the twentieth century (years). Source: National Center for Health Statistics. 2000 13 Decreasing price of computing power. The decreasing cost of computing power (1998 dollars per MFLOPS.) Source: Kurzweil (1999, pp. 320-321). 14 Decreasing price of illumination. 10 1 0.1 0.01 0.001 18 00 18 10 18 20 18 30 18 40 18 50 18 60 18 70 18 80 18 90 19 00 19 10 19 20 19 30 19 40 19 50 19 60 19 70 19 80 19 90 0.0001 Time price of light (hours of work per kilolumen-hour). Source: Nordhaus (1997). 15 Who is wealthier? Louis You Food Light Info tech A/C Entertainment Louis XIV (1638–1715) King of France (1643–1715) Housing Medicine 16 Economic growth. Joseph A. Schumpeter (1883-1950) “[I]t is the cheap cloth, the cheap cotton and rayon fabric, boots, motorcars and so on that are the typical achievements of capitalist production, and not as a rule improvements that would mean much to the rich man. Queen Elizabeth owned silk stockings. The capitalist achievement does not typically consist in providing more silk stockings for queens but in bringing them within the reach of factory girls in return for steadily decreasing amounts of effort.” Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy (1942). 17 Economic growth. 0 1000 1820 1998 Western Europe 450 400 1,232 17,921 Western Offshoots 400 400 1,201 26,146 Japan 400 425 1,201 20,413 Average Group A 443 405 1,130 21,470 Latin America 400 400 665 5,795 Eastern Europe & former USSR 400 400 667 4,354 Asia (excluding Japan) 450 450 575 2,936 Africa 425 416 418 1,368 Average Group B 444 440 573 3,102 World 444 435 667 5,709 Per capita income by region, selected years CE. (1990 International $.) Source: Maddison (2001) 18 World population growth. Year Population (millions) 25000 BCE 1 5000 BCE 5 1 CE 170 1000 CE 265 1400 CE 350 1800 CE 900 1900 CE 1625 2000 CE 6272 Source: Michael Kremer (1993), “Population Growth and Technical Change, One Million B.C. to 1990,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 108:3 (August), pp. 681-716. 19 Is intensive growth even possible? Thomas Robert Malthus (17661834) “It has been said that the great question is now at issue, whether man shall henceforth start forwards with accelerated velocity towards illimitable, and hitherto unconceived improvement; or be condemned to a perpetual oscillation between happiness and misery, and after every effort remain still at an immeasurable distance from the wished-for goal.” Malthus (1798), I.2. 20 Is intensive growth even possible? Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834) Malthusian population doctrine. Population (potentially) grows exponentially but food supply (potentially) grows only linearly. Any surplus above necessities leads to population growth, which reduces real wages back down to subsistence. Diminishing returns. David Ricardo (1772-1823) Image courtesy of the Warren J. Samuels Portrait Collection at Duke University. Because land is a fixed factor, food supply actually grows less than linearly. Rent of land sucks up all returns and brings growth to a halt. 21 What Malthus and Ricardo forgot. Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834) Diminishing returns. Wildly underestimated the potential for productivity growth. Malthusian population doctrine. David Ricardo (1772-1823) Image courtesy of the Warren J. Samuels Portrait Collection at Duke University. Missed the demographic transition. 22 Malthusian responses. Thomas Robert Malthus (1766-1834) When a Malthusian society generates economic surplus. Migration to new land. A Malthusian crisis. Technological, institutional, and organizational change to increase productivity. 23 What causes (intensive) growth? Resources help. Climate, geography. Guns, germs, and steel. Lack of resources helps. Hong Kong versus Argentina. The resource trap. 24 The spread of human populations. 25 The Neolithic era. Pleistocene takeoff (circa 50,000 B.C.E.) Evolution of brain or voice box? Cro-Magnon enter Europe (circa 40,000 B.C.E.) Cave painting (32,000-30,000 B.C.E.) from the Chauvet cave at Vallon-Pont-d'Arc in the Ardèche region of France. 26 Hunter-gatherer society. Dependence on natural foodstuffs: nomadism. Generate surplus with technological change. Common-pool problem. Migration when land abundant. Intergroup warfare when land scarce. Hunter-gatherers maximize population. 27 The first economic revolution. VMPL VMPHG VMPAGR N* Population (labor force) 28 Settled agriculture. Population pressure creates “demand” for settled agriculture. First stage: defending naturally occurring foodstuffs. Women cultivate crops by while men hunt. Climate, geography, resources create “supply” of settled agriculture. 29 Guns, germs, and steel. The major axes of the continents. 30 The advantages of Eurasia. Plant domestication. Large connected belt of Mediterranean climate. Wider availability of domesticable varieties (cereals). Animal domestication. Coevolution of humans and animals. Prevents mass extinctions during huntergatherer era. Evolved immunity to animal-borne diseases. 31 The Fertile Crescent. Sites of food production before 7,000 B.C.E. The geographical distribution of the seven Neolithic founder crops in the Fertile Crescent (yellow) of the Near East. Large map shows the distribution of wild chickpea (red line) in a core area (green line) within the upper reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (present-day southeastern Turkey/northern Syria). Inset maps show the distribution of founder cereal crops — einkorn wheat (cross indicates the putative site of its domestication), emmer wheat, and barley — and founder legumes (lentil, pea, bitter vetch). Blue lines delineate the range of genetic founder stocks for lentil and pea, and red lines the range of emmer wheat, barley, and bitter vetch (no data are available on their genetic founder stocks). Red lines also indicate the distribution of einkorn wheat, lentil, and pea beyond that of their genetic founder stocks. Source: Simcha Lev-Yadun, Avi Gopher, and Shahal Abbo, “The Cradle of Agriculture,” Science 2(288): 1602-1603, June 2000 33 The spread of agriculture to Europe. 34 The Indo-Europeans. Common origins of European and IndoIranian languages (4000-2500 B.C.E). Who were the Indo-Europeans? Theory 1: pastoral nomads. Mobility of domestic horse, wheeled carts. Economic advantages of pastoralism. Capital intensity. The secondary-products economy. Theory 2: masters of settled agriculture. Genetic evidence. Population pressure from settled agriculture. 35 Diffusion of innovation. 1500 2000 2500 WOOL 3000 HORSE 3500 PLOUGH, CART 4000 4500 Reconstruction of Ötzi the ice mummy (c. 3300 BCE), in the South Tyrol Museum of Archeology, Bolzano, Italy. 5000 MILKING? 5500 6000 6500 Years BCE AGRICULTURE 36 Bronze Age Europe. Baltic Germanic Slavic Celtic Italic Greek 37 Early cities and civilizations. Jericho (c. 7,000 BCE) Sumeria and Baylonia (c. 31001600 BCE) Egypt (c. 2705-332 BCE) Mycenaea (c. 2000-1350 BCE) 38 The urban revolution. Irrigated settled agriculture. Economic surplus. Specialization. Bull-headed lyre from the Royal Tombs of Ur. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archeaology and Anthropology. Artisans. Soldiers. Kleptocracy. Bureaucrats. 39 North’s theory of the state. The state (monarch) is a revenuemaximizing natural monopolist in the use of force. The minimum efficient scale of defense. Revenue-maximization and the Laffer curve. 40 Revenue maximization. The Laffer curve Revenue 0% t* 100% Tax rate 41 “Oriental despotism.” High MES of agricultural production. Labor-intensive irrigation projects. Slave or near-slave labor force. Workers “deskilled” and can’t appropriate benefits of innovation. Appropriation of surplus by aristocracy. Lavish monumental construction rather than reinvestment. Specialists focus on luxury goods for aristocracy. Low rate of technological change. Slow economic growth. 42 The Phoenicians and Greeks. 43 The Roman Empire. 44 The Rise of Rome. Agriculture. Irrigation and servile production. But, unlike Egypt, agriculture private: the Villa system. The Pont du Gard aqueduct, near Nîmes, France. Organization and law. Military technology. Discipline and large numbers. 45 Early Roman economic policy. Head of the Emperor Augustus (ruled 27 B.C.E. – 14 C.E.), from the Kelsey Museum, University of Michigan. Importance of trade and commerce. Octavian defeats Antony (31 B.C.E.) The pax romana and the Mediterranean “common market.” 46 The Roman Empire about 117 C. E. 47 International trade in the Roman era. 48 The fall of Rome. External causes. Change in military technology? Learning by “barbarians.” Internal causes. End of expansion eliminates source of revenue. Need to “bribe” political challengers. Bread and circuses. Tax exemptions for nobility. Spiraling fiscal crisis. 49 Roman fiscal crisis. Roman coin bearing the likeness of the Emperor Diocletian (284-305 C.E.) Emperors raise tax rates to meet revenue demands. Tax base erodes as goods and services flee the money economy. Reduced tax base leads to further increases in the tax rate, and so on in a vicious cycle. Tax revenue = tax rate * tax base 50 Monetary Policy. Debasement of the currency (another kind of tax) leads to hyperinflation in the third century. Gresham's Law. (“Bad money drives out good.") 51 Government controls. Diocletian reforms. Strict wage and price controls. In-kind system of taxation and requisition. Constantine (308-337) ties workers to the land. “Demonetizing” the economy. 52 Barbarian invasions. Germanic expansion. Population increase and Huns. Augustulus Augustulus deposed by barbarians in 476. How dark the “Dark Ages”? Evidence of population decline. From roving bandits to sedentary bandits. 53 The feudal system. Change in the MES of military technology. The great stirrup controversy. Feudalism as a “contract.” Exchange of work for defense. Why an in-kind exchange? Serfdom: tying workers to the land. Charlemagne crowned emperor by Pope Leo III (800 C.E.), from Labor shortage and rent distribution. Example: professional sports. Grandes Chroniques de France (14th Century), Bibliothèque Nationale de France. 54 Feudalism as a system of rights. Although full-grown feudalism was largely the result of the breakdown of older government and law, it both inherited law from the past and created it by a rapid growth of custom based on present fact. In one sense it may be defined as an arrangement of society based on contract, expressed or implied. The status of a person depended in every way on his position on the land, and on the other hand land-tenure determined political rights and duties. The acts constituting the feudal contract were called homage and investiture. The tenant or vassal knelt before the lord surrounded by his court (curia), placing his folded hands between those of the lord, and thus became his ‘man’ (homme, whence the word homage). … The lord in turn responded by ‘investiture’, handing to his vassal a banner, a staff, a clod of earth, a charter, or other symbol of the property or office conceded, the fief (feodum or Lehn) as it was termed …. This was the free and honourable tenure characterized by military service, but the peasant, whether serf or free, equally swore a form of fealty and was thus invested with the tenement he held of his lord. The feudal nexus thus created essentially involved reciprocity. — The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History 55 The manorial system. Villein tenancy. Disappearance of slavery. The custom of the manor. Demesne obligation. Three days of week-work on the lord’s land. An input-sharing contract. October, from Les très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c. 1412). The Chantilly Museum, Paris. 56 Early medieval agriculture. Traditional individualistic subsistence agriculture. Shared common “wastes” with little common-pool pressure. “Sedentary pastoralism” takes precedence over cultivation of arable. Eventually: communal control over common-field grazing. 57 Evolution of the manorial system. Population growth leads to nucleation. Peasants leave hamlets and assemble in villages. Arable of hamlets merged to become village arable. June, from Les très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c. 1412). The Chantilly Museum, Paris. 58 Evolution of the manorial system. Population growth leads to increased demand. Labor transferred from pastoralism to cultivation of the arable. “Cerealization” and “destocking.” “Common of shack”: grazing on the fallow arable. Final element: scattering of arable holdings. June, from Les très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c. 1412). The Chantilly Museum, Paris. 59 Crop rotation. Three-course rotation in wide use by ninth century. Spring crop: Oats/barley or peas/beans. Harvested in summer. Autumn sowing of wheat or rye, harvested following summer. A year fallow. Four seasons and seasonal labors. From Bartholomaeus Anglicus (Bartholomew the Englishman), On the Properties of Things. France, Le Mans 15th Century. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Nitrogen fixing by soil bacteria. Manure from pasturing. 60 The open-field system. 61 Representative village. Physical structure. Division into arable and non-arable land. “Waste” for grazing. Arable divided into two or more fields. Hundreds of acres each. Arable subdivided into elongated narrow strips. But waste not subdivided. 62 Representative village. Ownership structure. Villeins, copyholders, and freeholders. Not much practical difference. OFS as a village system, not a manorial system. Commons owned collectively. Not “unowned.” 63 Representative village. Institutional structure. Management of the Commons. Changeover from private to collective rights. Use of commons. Joint expenses. Manor court or village meeting. Set planting and harvesting dates. Prevented overuse of commons. Controlled private exchange of strips. 64 Representative village. Technological structure. Little specialization in production. Except near big cities. Specialized farms didn’t use the OFS. High transportation and transaction costs. Some activities collective. Grazing, plowing, harvesting. Some activities private. Sowing, weeding. 65 The OFS: economic analysis. Fine-tuned adaptation to diversified autarkic production. Pastoralism and crop rotation. Many tasks, with different levels of economies of scale and different costs of monitoring. Manage tasks collectively when economies of scale high and monitoring costs low. Assign private property rights when economies of scale low and monitoring costs high. July, from Les très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c. 1412). The Chantilly Museum, Paris. 66 Scattering. 67 Scattering: early explanations. Size of plow team. Land in proportion to contribution. But scattering observed even when light plow used. Desire for equality. But there were many inequalities among peasants. Partible inheritance. But this applies only to holders in fee simple. Assarting. Creating new arable form the waste. General problem: why does scattering persist? Active markets in strips. 68 Scattering and risk. McCloskey: scattering as a form of insurance. Variability of climate and soil over small areas. Scattering as portfolio diversification in the absence of other assets. 69 Problems with the risk hypothesis. Landlords provide de facto “charity.” Livestock another portfolio asset. Optimal risk sharing through combination of rental, wage, and share-cropping contracts. 70 Scattering and the open-field system. Dahlman: scattering helps preserve OFS. By increasing costs of private enclosure, scattering reduces “hold-up” threats. Scattering protects the system against the individual. Fenoaltea: stands Dahlman on his head. Collective activities (especially harvesting) capacity constrained. Not all parts of all fields can be harvested in some years. Scattering protects the individual against the system. A different sort of risk-diversification argument. 71 The success of the OFS. Year W. Europe All Europe* 1000 12-15 million 15-20 million 1300 45-59 million 60-70 million Population densities highest where the manorial/OFS was most extensive. Northern France, Northern Italy. Population growth in Eastern Europe the result of migration. *All Europe includes Norway, Sweden, most of Eastern Europe, and Christian Spain. 72 Results of population growth. From 11th to 13th century, a frontier movement. Clearing the waste. Colonizing Eastern Europe. The Crusades as a frontier movement. 73 Thirteenth century: looming crisis. Frontier movement ceases, population growth continues. General increase in land rents. Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Harvesters (1565 ) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Increase in relative prices of cereals. Some shift from pasture to cultivation. Diminishing returns and declining real wage. 74 Thirteenth century: response. Refeudalization: return to direct cultivation of the demesne. Feudal obligations transformed into money rents in many places by 11th century. Money rents seen as fixed: origin of the word “farm.” Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Harvesters (1565 ) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York A farmer (fermier) held a right to rents that were fixed or firm (ferme). Why return to feudal obligations? 75 Why refeudalization? Lords dig in their heels. Fixed rents allows peasants to capture the gains from increasing land rents. Return to demesne avoids renegotiation costs. Proto-enclosure. Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Harvesters (1565 ) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York A move toward specialized production? Either way: the failure of institutional transformation. 76 The calamitous fourteenth century. Population of Western Europe, 1200-1550 (millions). 1200 61 1400 45 1250 69 1450 60 1300 73 1500 69 1350 51 1550 78 Albrecht Dürer, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1498). 77 The calamitous fourteenth century. Population of England, 1086-1603 (millions). 1086 1.1 1374 2.25 1348 3.76 1377 2.23 1350 3.13 1400 2.1 1360 2.75 1430 2.1 1369 2.45 1603 3.78 Albrecht Dürer, The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1498). 78 Malthusian crisis. Famine. War. The Black Death. Les Quatres Morts, from the Danse Macabre of the Cemetery of the Innocents, Paris, 15th century. Bubonic plague, 1348-51 Recurred many times through 15th century. Population didn’t stop falling until mid 15th century, and did not recover until 16th century. 79 Economic effects of population decline. S P P’ D D’ Supply and demand for agricultural products in Europe before (D) and after (D’) the plague. Price fluctuations, with general deflation after 1375. Prices of agricultural goods fall relative to manufactured goods. Real wages increase. Rents decline, as does cultivation of marginal lands. 80 Institutional effects of population decline. Transformation of servile obligations into property rights. Competition for peasant labor leads to attractive rental contracts. Rents fixed — renegotiated on death of peasant. Eventually, life leases become hereditary by custom. Inflation reduces value of “quit rent” to nominal sum. Hereditary leases become rights in fee simple. Soil tilled by free tenants and wage workers. Trading rights for revenue. 81 Institutional transformation. Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Harvesters (1565 ) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Like the 13th century, the 16th century was a period of rising population and increasing land rents. But this time Europe responded with an institutional innovation that led to continual increases in productivity. 82 The enclosure movement. Physical enclosure. Legal enclosure. Voluntary enclosure. Parliamentary enclosure. 83 The timing of English enclosure. Period <1550 1500-1599 1600-1699 1700-1799 1800-1914 >1914 Percentage enclosed. 45 2 24 13 11.4 4.6 Percentages approximate. Source: Wordie (1983). 84 Transaction costs of enclosure. Voluntary enclosure. Required unanimity, side-payments. Complex property law geared to protect hereditary estates from profligate descendants. Enclosures with highest net benefits take place first. Parliamentary enclosure. Case-by-case exemption from common law. Majority not unanimity. A form of eminent domain. Not important until mid-18th century. “Hardest” enclosures Parliamentary. 85 The benefits of enclosure. Benefits of specialization and trade. Greater appropriability of innovation. Reduced costs of collective decisionmaking. Enclosure for pasture in Britain reflected Britain’s growing comparative advantage in wool. 86 The benefits of enclosure. Source: McCloskey (1975) Enclosed land rented for twice common-field land. £2.1 million per year gain in productivity, about 1.5% of national income or about 3.5% of agricultural income. Rate of return of 17% per year. An average village 13% more productive. 87 Institutional transformation. Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Harvesters (1565 ) Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Like the 13th century, the 16th century was a period of rising population and increasing land rents. But this time Europe responded with an institutional innovation that led to continual increases in productivity. Why? A more developed market economy. 88 Institutional transformation. Agricultural transformation. The enclosure movement. Commercial transformation. The requickening of trade. The development of cities. Political transformation. The rise of the nation-state. Mercantilism. 89 Rise of the nation-state. Increase in the MES of military technology. Lower communication and coordination costs. Population increase. Change in military technology? Pike and longbow. Gunpowder. The Battle of Crécy (1346). Jean Froissart, Chronicles. Flanders, 15th Century. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. 90 Rise of the nation-state. Increase in the MES of military technology. Increase in the geographic extent of dominions. Overcoming “medieval particularism.” “Shakeout” and fiscal crisis among rulers. The Battle of Crécy (1346). Jean Froissart, Chronicles. Flanders, 15th Century. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Search for new sources of revenue leads to institutional change. 91 Institutions and economic growth. Efficient institutions. Secure property rights. Reduce transaction costs. Positive-sum game. Inefficient institutions. Redistribute wealth rather than create wealth. Monopolies, trade restrictions. Zero-sum (negative-sum) game. 92 Market integration. Tolls and internal customs barriers. Coinage. Weights and measures. Law. Market-enhancing institutions. Rembrandt, detail from The Moneychanger (1627), Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. 93 Tolls and internal customs barriers. Not only tariffs at political boundaries but also internal tolls. Roads and waterways. Markets and towns. Customs barriers every six miles on the best roads. More than 60 tolls on the Rhine by the end of the Middle Ages. In France, still 1600 tolls at the time of the French Revolution (1789). Rembrandt, detail from The Moneychanger (1627), Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. 94 Tolls and internal customs barriers. England: monarch opposed tolls without a quid pro quo of service. Royal permission needed. Inhabitants could demand audit. Gradual disappearance of tolls. Separated foreign from domestic: “customs” vs. “tolls.” National customs system, 12751350. Early power of monarchy. Rembrandt, detail from The Moneychanger (1627), Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. 95 The turnpike system. 1660 through eighteenth century. Best one-fifth of English roads. Privately constructed by “turnpike trusts.” “The benefits of these turnpikes appears now to be so great, and the people in all places begin to be sensible of it, that it is incredible what effects it has already had upon trade in the counties where it is more completely finished.” — Daniel Defoe 96 Coinage. Unification quicker and easier. Theory of money. England: unification under Henry II in 12th century. Depreciation ceases. France: a talent for manipulating coinage. Germany: coinage remains largest obstruction to internal trade. Rembrandt, detail from The Moneychanger (1627), Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. 97 Weights and measures. In Middle Ages, varied not only by locality but also by type of product. Aids cheating, raises transaction costs. England leader in unification, but local weights and measures not abolished until statute of 1835. “... to bring the whole of His Majesty’s kingdom within the same statutes and within the same system of weights and measures, an undertaking very worthy of our great King …” — Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1665) Rembrandt, detail from The Moneychanger (1627), Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. 98 Evolution and unification of law. On the continent, the rediscovery of Roman law. In England, parallel development of Common Law. Battle against royal monopolies. The Law Merchant. Enforcement at the Champagne Fairs. Rembrandt, detail from The Moneychanger (1627), Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. 99 Economic association without kinship. Trading within ethnic networks. Ethnic culture and institutions promote trust, enforce sanctions. The Community Responsibility System. Intergroup trading. Sanctions imposed at group level. The Individual Responsibility System. Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Georg Gisze, a German merchant in London (1532). Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin. As groups grow, difficult to monitor members effectively. Rise of legal institutions of nation-state and law merchant. 100 Other market-promoting innovations. Bills of exchange. Development of banking. Insurance. Separation of marine insurance from financing. Double-entry bookkeeping. Helps detect errors. Separation of business account from family account. 101 Guilds. Medieval guilds. Institutional structure for preserving and diffusing productive knowledge. Institutional structure for coordinating commitments and enforcing contracts. Decline of guilds. Rembrandt, The Syndics of the Clothmaker's Guild (The Staalmeesters) 1662. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. Medieval guilds integrated insurance, safety-net, and other functions. Competition from rural industry. State policy weakens guilds in England and the Netherlands, strengthens them in France. 102 Mercantilism. Association of state power with economic power. Microeconomic. System of economic regulation Macroeconomic. Regulation of international trade and finance. System of economic thought. A sea depot in Amsterdam, 1750. 103 Patents and Monopolies. $ DWL loss represents foregone gains from trade. CS Right to exclude others from competition. Monopoly transfers wealth from consumers to producers (PS) Pm PS DWL Pc MC, AC MR Qm Creation of “artificial” property rights. D Qc Merchants willing to pay monarch up to PS for right to monopoly. Dead-weight efficiency loss (DWL). 104 Patents and Monopolies. Origin of the word patent. Typical Elizabethan monopolies: Saltpeter, gunpowder, salt, paper. In 1603, Elizabeth declares monopolies contrary to common law. In re: playing cards. Pressure from merchants and courts. Statute of monopolies (1625). Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603). Ruled 1558-1603. Attributed to Nicholas Hilliard. The Tate Gallery, London. 105 Trade and monetary policy. Balance of trade. Control of export of bullion. Staple policy. Town as entrepôt. Policy of provision. Tariffs, etc., to retain or attract certain goods. Sumptuary laws. A sea depot in Amsterdam, 1750. 106 Mercantilism as a system of ideas. Balance of trade. Analogy with individual account. From Italian accounting practices. Fallacy of composition. Struggling to understand growth in a zero-sum framework. Adam Smith attacks “the mercantile system.” A sea depot in Amsterdam, 1750. 107 Institutions and economic growth. Why did some countries create efficient institutions? Why did others create inefficient institutions? 108 France. Charles VII takes over a destroyed country after Hundred Years War, 1422. Medieval sources of revenue depleted by war. Creating nation state requires large and growing revenues. Jean Fouquet, portrait of Charles VII of France, c. 1444. The Louvre, Paris. 109 France. Charles effective in restoring order. Estates General must approve levies. Estates anxious to restore order. Special right to levy turns into a permanent right. Excluding nobles and clergy from taxation. Jean Fouquet, portrait of Charles VII of France, c. 1444. The Louvre, Paris. 110 France. Guilds become fiscal agents for the crown. Taxation more effective. Compare JP system in England. Strengthens guilds. Administrative bureaucracy. Jean Fouquet, portrait of Charles VII of France, c. 1444. The Louvre, Paris. 111 Colbertism. Jean-Baptiste Colbert. Finance minister under Louis XIV (1661-83). Colbertisme synonymous with mercantilism. Economic reforms. Efforts to reduce “particularism.” But favored state monopoly and industrial control. Origin of laissez faire. Frustrated by royal need for revenue. Prohibitive tariffs lead to war with the Netherlands. 112 Spain in 1492. Reconquest ends with capture of Granada, last Moorish stronghold. Unification and consolidation of power. Cortes grant taxing power. Taxes increase 20 times between 1470 and 1540. Expulsion of the Jews (and then Moriscos in 1609). Loss of artisanal, commercial, and agricultural skills. Columbus sets sail. Queen Isabella of Spain. Ruled 1479-1504. 113 The Mestas. Sheep guild. Granted Royal privilege in 1273. Transhumance rights in exchange for funds to finance reconquest. Decree of 1501 reserves in perpetuity all land on which sheep have ever grazed. Effect on enclosure. Price controls on cereals. Consulado of Burgos. Transhumance routes in Spain. 114 The Spanish empire. 115 The Spanish empire. Monopoly control. Casa de Contratación. Prohibition of colonial industry. Bullion and Inflation. Looted and mined gold and silver floods Spain and Europe. Prices increase by more than a factor of three in Spain, and a factor of five in Brabant and England. 116 The Spanish empire. 120 100 80 60 40 20 15 01 15 11 15 21 15 31 15 41 15 51 15 61 15 71 15 81 15 91 16 01 16 11 16 21 16 31 16 41 16 51 0 Index of silver imported to Seville, 1501-1660. (1591-1600=100). Source: John H. Munro, “The Monetary Origins of the ‘Price Revolution.’” 117 The decline of Spain. Revenues. Americas less than 20 percent. Netherlands largest source. Costs. Far exceed revenues. Hapsburgs spend on military and wars to expand empire. Effects. Borrowing and bankruptcy. Fiscal spiral. Titian, Charles V Seated (1548). Pinakothek Munich. Confiscation, monopoly, sale of titles. 118 The Netherlands. Passes from Burgundy to the Hapsburgs (1477). Both Burgundians and Hapsburgs encourage growth and trade. Small taxes on many items in exchange for secure property rights. Discourage monopolies, guilds. The goose that lays the golden eggs? The Netherlands in 1543. 119 The Netherlands. Increased exactions lead to successful rebellion (1572-1581). Antwerp sacked; commercial leadership moves to Amsterdam. By 17th century, Dutch become commercial leaders of Europe. Economic diversification. The Dutch East India Company (1602). “The First Modern Economy.” Replica of Henry Hudson’s schooner, the Half Moon. 120 England. Government funded as an extended household. Expenditures exceed revenues from Crown lands. Sale of land to meet shortfall. Elizabeth sells 25 per cent after 1588 war with Spain. James I sells another 25 per cent. Charles I (1625-1641) sells the rest. Parliament controls taxes and customs. King James I (ruled 1603-1625). 121 Stuart England. Stuarts seek revenue outside parliamentary control. New customs impositions. Sale of monopolies. Expansion of peerage. Packing the House of Lords. James: a baronet for £1,095; price later falls to £220. Loans secured under threat. Purveyance. King Charles I (ruled 1625-1641). Charles I seizes £130,000 of bullion stored in the Tower of London (1640). 122 Stuart England. Parliament withholds revenues. Demands respect for traditional property rights. Common Law courts oppose monopolies. Coke invokes Magna Carta. Charles responds with Royal Prerogative. Prerogative courts. Special laws for individuals. Star Chamber. Fires Coke and other judges. Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634). 123 The English Civil War. Coalition builds against the Crown. Marginal incentive to support the king declines as costs of other people’s privileges mount. Execution of Charles I (1649). Unlike continental monarchs, English king has no standing army. 124 The English Republic. Star Chamber Abolished. Restrictions against monopolies enforced. Regular standing parliament. Royal administrative mechanisms abolished. Act of 1660 abolished feudal tenures, effectively making England a fee simple society. Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658). 125 The Restoration. Cromwell unable to find a stable form of government. Son proves a poor successor. Stuarts restored to power (1660). Royal abuses begin again. “Rechartering” the Whigs out of parliament. King Charles II (ruled 1660-1685). James II turns on his own followers (1686-88). 126 The Glorious Revolution. Parliament welcomes invasion by William of Orange and Mary, Protestant daughter of James II. Parliamentary supremacy. Fiscal revolution underpins political revolution. A self-enforcing constitution. William III (ruled 1689-1702. Mary II (ruled 1688-1694). 127 A self-enforcing constitution. Required parliament’s assent for major policy changes. Allowed wealth-holders to veto what wasn’t in their interest. Ways of reneging unilaterally eliminated. Limited Crown sources of funds. Audit expenditures. Prerogative courts abolished. Judicial tenure. John Locke (16321704 ). Published Two Treatises of Government (1690). Self enforcing. Credible threat of dethronement. 128 The fiscal revolution. Parliament agrees to put government on sound financial footing in exchange for veto power. Evidence: lenders now willing to supply funds. After 1688, government has access to unprecedented funds. Tenfold increase, 16881697. William III (ruled 1689-1702. Mary II (ruled 1689-1694). 129 The Industrial Revolution. When? 1780-1830. Was it a “revolution”? No: Cameron. Yes: Landes. 130 The Industrial Revolution. Industrialization vs. economic growth. U. S. wealthier than Britain in 1800, but little industrialization. Growth can come from improvements in traditional activities, e.g., agriculture. Per capita growth not “revolutionary” during industrial revolution. Steady balanced growth. But denominator growing rapidly. Increased output sustains rapid population growth. Did growth in “new” sectors contribute to growth in “old” sectors? 131 The Industrial Revolution. Qualitative transformations. Technological transformations. Energy: animal to water and steam power. Materials: wood to iron and steel. Organizational Transformation. The factory system. James Watt’s steam engine, 1769. 132 Britain in 1700. Population on England and Wales: 5.2 million. Would grow to 9.1 million by 1800. Would almost double again to 17.8 million by 1850. Ogilby’s Britannica (1675) 133 Britain in 1700. English peasant ate better than continental counterpart. Spent lower proportion of income on food. Implies increased demand for manufactured goods. Lower tolls and improved transportation. Canals and turnpikes. More urban. By 1800, 25% in cities larger than 5,000 persons. Compare with 10% in France. Cities centers of commerce. 134 Britain in 1700. Increased extent of the market. Large internal market. Merchant fleet spurs international trade. Relative wealth of peasantry. Focus on standardized, low-cost items. Useful also in trade with Asia, Africa, and Americas. Quantity not quality: search for lower costs. 135 Manufacture in 1700. Local crafts shops. But pressure on urban guilds from rural industry. The putting-out system. Woolens dominate. 70% of English exports in 1700. 50% in 1770. Not localized: spread all over England. Link to labor freed by enclosure. 136 The putting-out system. Merchant clothier. Commissions spinners and weavers. Provides wool. Hires workers for finishing and dyeing. Cottagers. Own tools: handloom, spinning wheels. Division of labor within household. Men weave, women spin. Children and hired labor. Paid on piece-rate basis. May have garden, cows, etc. Also called the “domestic” system. Continue to participate in agriculture. 137 Early textile innovation. John Kay’s flying shuttle (1733). Spinning becomes a bottleneck. Wyatt-Paul spinning frame (1738). Never technologically successful. Difficulty of wool as material. 138 The cotton textile industry. Cotton arrives in Britain from India. Efficient, skill-intensive hand production. Instant popularity of colorful calicoes. Woolens industry clamors for protection. Wall hanging (detail). Painted and dyed cotton. Madras-Pulicat Region c. 1640-50. Act of 1700 forbids import of printed fabrics. Act of 1719 forbids wearing calicoes. British entrepreneurs seize opportunity. Using linen for warp and cotton for weft. Ancient right to produce fustian. 139 The cotton textile industry. Import prohibitions encourage development of indigenous British cotton textile industry. Originally, cotton cloth produced by domestic system, on woolens model. Rise of the “fustian masters.” Tendency of weaving to concentrate. Manchester and Lancashire. Favorable ground for mechanical invention. Cotton more easily mechanized than wool. Trajectory of mass production. 140 Innovation in cotton spinning. Hargreaves’ jenny. Patented 1770. Basically a multi-spindle spinning wheel. Powered by a single human. Arkwright’s water frame. Based on Wyatt-Paul and thus not patentable. Uses two rollers. Designed for non-human power. 141 Innovation in cotton spinning. Hargreaves’ machines smashed by angry spinners. Patent held invalid. Hargreaves flees to Nottingham and dies in 1778. By 1788, 20,000 jennies in England. Completely ousts spinning wheel in Lancashire, which gives up wool for cotton. 142 Innovation in cotton spinning. Sir Richard Arkwright (1732-1792) Itinerant barber and hair merchant. Persuades Nottingham hosiers to back large-scale water-driven factories. Makes strong warp thread, allowing all-cotton cloth. Arkwright dies with a fortune of £500,000. Mather Brown, Portrait of Sir Richard Arkwright (1790). New Britain Museum of American Art. 143 Innovation in cotton spinning. Crompton’s mule (1779) Combined principles of water frame and jenny. Produced thread with fineness of jenny and strength of water frame. A “dominant design”: improved but never superseded until the late nineteenth century. 144 Innovation in cotton spinning. Mule spinning, mid-nineteenth century. 145 Innovation in weaving. Power loom: Edmund Cartwright (1787). Catches on slowly as engineering standards improve. Speed/breakage tradeoff. Technical advantage of 7.5:1 by 1820. Single operative tends more looms rather than increased output per loom. 146 The British textile industry. Date £ (thousands) % total exports 1784-86 766 6.0 1794-96 3,392 15.6 1804-06 15,871 42.3 1814-16 18,742 42.1 1824-26 16,879 47.8 1834-36 22,398 48.5 1844-46 25,835 44.2 1854-56 34,908 34.1 British exports of cotton textiles. Import substitution turns into export powerhouse. Leads British economic growth into 19th century. Surpasses woolen trade as principal export by 1803. More export oriented than woolens. Britain surpasses India in 1790 as largest exporter of calico, not to be overtaken until 1933 (by Japan). 147 Organizational transformation. Crafts production. The putting-out system. The factory system. Jedediah Strutt’s Milford mills. 148 A paradox? The enclosure movement. Move way from collective “team” working of village land. Unbundling of joint-ownership rights. The factory system. Move to collectively organized modes of production. Ownership rights to capital unified in joint-stock company. 149 The factory system. What is a factory? Expensive or indivisible technology. The concentration of workers in a single location. Close monitoring or supervision of work. “Factory discipline.” 150 Monitoring and supervision. The putting-out system. Contractor relationship. Product monitoring. Pecuniary incentives. The factory system. Employee relationship. Process monitoring. “Factory discipline.” 151 The factory system in cotton. 500 450 400 Power loom perfected. 350 300 Factory workers 250 Handloom weavers 200 150 100 50 1861 1856 1851 1846 1841 1836 1831 1826 1821 1816 1811 1806 0 Factory workers and handloom weavers in Britain, 1806-1862 (in thousands). Source: B. R. Mitchell, British Historical Statistics. Cambridge University Press, 1988, p. 376. 168 The factory system in cotton. Early factory workers. Women and children. Oldknow employs men in agriculture. Poorhouses. Need to build dormitories. By 1784, key position in spinning goes to adult males. The multicellular mill. Recreating the cottage contracting system within factories. Master spinner responsible for supervision, hiring. But doesn’t own tools (machines). Majority of child labor employed by masters, not capitalists. 169 The rise and decline of Britain. Aspects of British industrial success. Industrial organization. Industrial districts. International trade. The British Empire. Free trade. The debate over British industrial decline. Did Britain decline? Theories of decline. Culture. Technological trajectories and timing. 170 Industrial organization in Britain. When an industry has thus chosen a locality for itself, it is likely to stay there long: so great are the advantages which people following the same skilled trade get from near neighbourhood to one another. The mysteries of the trade become no mysteries; but are as it were in the air, and children learn many of them unconsciously. Good work is rightly appreciated, inventions and improvements in machinery, in processes and the general organization of the business have their merits promptly discussed: if one man starts a new idea, it is taken up by others and combined with suggestions of their own; and thus it becomes the source of further new ideas. And presently subsidiary trades grow up in the neighbourhood, supplying it with implements and materials, organizing its traffic, and in many ways conducing to the economy of its material. — Marshall, Principles of Economics, IV.x.3. Alfred Marshall, 1842-1924 Industrial districts. External economies. 171 Lancashire. Original advantages. Poverty. Pastoral farming lends itself to small-scale enterprise. Indigenous textile tradition. Woolens under Yorkshire influence and linens under Irish influence. Climate. Cotton “hydroscopic.” An east wind reduces output and quality by 10 per cent. An Industrial Landscape in 1833: Swainson, Birley and Co., near Preston, Lancashire, England. Water and coal. Lack of institutional constraint. Manchester a new town. Grows from 7th largest in 1775 to 3rd largest in 1801. 172 Lancashire. External economies. Transportation. Port of Liverpool develops with Manchester. Canals, turnpikes, and railways. World’s first passenger railway. Later, telegraph and telephone turn Manchester into communications center. Markets. Cotton exchanges create thick market for worldwide imports. Power loom and mule adapted to wide variety of cotton types and quality. Worldwide network of commissioning agents. The Manchester Cotton Exchange. 173 Lancashire. External economies. Vertical specialization. Low barriers to entry. Tens of thousands of establishments. Specialization by type of yarn or cloth. One firm may lease space in several mills and one mill may contain several firms. “Flexible specialization.” Subsidiary industries. An Industrial Landscape in 1833: Swainson, Birley and Co., near Preston, Lancashire, England. Textile machinery industry. Banking and finance. Transportation and communication. 174 Lancashire. International trade. Sales worldwide, but especially to subtropical areas of India, China, Latin America. Percent value of cotton exports 1820 1850 1896 Europe 65.5 34.3 18.9 America 26.1 29.1 18.5 USA 7.2 8.9 3.6 Latin 17.8 18.0 15.0 Levant 2.5 9.2 7.9 Asia 5.2 24.3 43.4 India 18.5 26.6 China 3.6 8.5 1.7 5.3 Africa 0.6 175 The British Empire. Beginnings in Mercantilist trading monopolies. East India Company (1600). Trading companies take on political and military functions. Creating trading institutions and preserving openness of markets. British government takes over functions of trading companies. East India Company nationalized 1773. Monopoly abolished 1813. 176 Britain and Free Trade. Smith’s Wealth of Nations attacks mercantilism. The Corn Laws. Import controls after Napoleonic wars. Ricardo discovers comparative advantage. Anti-Corn-Law League founded in Manchester, 1836. Corn Laws repealed, 1846. Reflects shift of economic power from agriculture to manufacture. David Ricardo (1772-1823). Image courtesy of the Warren J. Samuels Portrait Collection at Duke University. Anglo-French commercial treaty (1860) virtually eliminates tariffs. 177 The decline of Britain. The Crystal Palace, site of the Great Exhibition of 1851, which showcased British technology to the world. Relative or absolute decline? Timing of decline. 178 The decline of Britain. GDP per capita in 1990 dollars. 25000 20000 Germany 15000 UK USA 10000 5000 0 1820 1870 1900 1913 1950 1973 1992 Source: Angus Maddison, Monitoring the World Economy, 1820-1992. OECD, 1995, p. 23-24. 179 The decline of Britain. Britain retains lead in traditional industries. Textiles, textile equipment, shipbuilding, cable. A Bessemer steel converter. Kelham Island Museum, Sheffield, England. Britain cedes lead to US and Germany in new areas. Organic chemicals, electrical products, steel. 180 The decline of Britain: hypotheses. Culture. Sons of nouveau riche capitalists study classics at Oxford and Cambridge. Culture of the gentleman: antitechnology and anti-business. Educational system. Britain relies on on-the-job training. No system of technical education. Costs of empire. Civil service drains off talent. 181 The decline of Britain: hypotheses. Institutional inertia. The “disadvantages” of an economic head start. The ring spinning frame. Technological trajectories. The case of the ring spindle. 182 “Neoclassical” growth theory. Y = f(K, L) Robert Solow (1924-) But: growth in capital and labor don’t account for growth in GDP. The “residual.” 183 “Neoclassical” growth theory. Y = f(K, L; ) Robert Solow (1924-) But: growth in capital and labor don’t account for growth in GDP. The “residual.” 184 “Neoclassical” growth theory. Y = f(K, L; ) Robert Solow (1924-) But: growth in capital and labor don’t account for growth in GDP. The “residual.” Or else K and L have “improved.” Either way: something is missing. Knowledge. 185