cns examination

advertisement

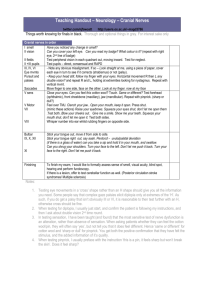

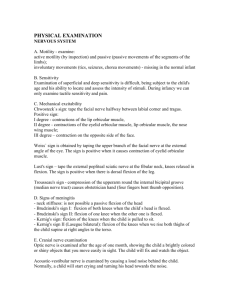

EXAMINATION OF THE NERVOUS SYSTEM Three important questions govern the neurological examination: Is the mental status intact? Are right-sided and left-sided findings in the patient symmetric to each other? If the findings are asymmetric or abnormal, does the causative lesion lie in the central nervous system or the peripheral nervous system? TECHNIQUES | OF EXAMINATION EXAMINATION | OF MENTAL STATUS EXAMINATION | OF CRANIAL NERVES EXAMINATION OF THE SENSORY SYSTEM TECHNIQUES OF EXAMINATION: Following should be examined in a patient during the nervous system examination. Top Mental status: Appearance and behavior, speech and language, mood, thoughts and perceptions, cognition. Cranial Nerves I to XII Motor system: Muscle bulk, tone, and strength; coordination, gait, and stance. Sensory system: Pain, temperature, position, vibration, light, touch discrimination. Deep tendon reflexes and superficial reflexes. EXAMINATION OF MENTAL STATUS: Top Examination of mental status begins with history taking. While taking the patient’s history carefully examine the patient’s level of alertness and orientation, mood, attention and memory. You will also learn about the patient’s insight and judgment, as well as any recurring or unusual thoughts or perceptions. Components of the mental status examination include: Appearance and behavior Speech and language Speech and language Thoughts and perceptions Cognitive function, including memory, attention, information and vocabulary, calculations, and abstract thinking and constructional ability. APPEARANCE AND BEHAVIOR: This aspect can be assessed during the history taking. Doctor must make a note of the aspects like level of consciousness, posture and motor behavior, dress, grooming, and personal hygiene, facial expression, manner, affect, and relationship to persons and things. LEVEL OF CONSCIOUSNESS – First consider the patient's level of consciousness, as this may determine what can be done with the rest of the examination. Observe if the patient is awake and alert. Does the patient seem to understand your questions and respond appropriately and quickly, or is there a tendency to lose track of the topic and fall silent or even fall asleep? Lethargic patients are drowsy but open their eyes and look at you, respond to questions, and then fall asleep. Obtunded patients open their eyes and look at you, but respond slowly and are somewhat confused. Clouding of consciousness may occur as a result of acute diffuse cerebral dysfunction, e.g. in cerebral hypoperfusion, metabolic disease or encephalitis. Focal lesions of the thalamus, especially if medial and bilateral, can also cause delirium, and lesions of the brainstem, reticular activating system cause a markedly impaired conscious level. If a wide-awake patient without severe dementia fails to respond, he or she may have a specific aphasia in the domain of repetition, or hysterical or depressive pseudo-dementia. If the patient doesn’t seem to respond to the questions asked, you can further stimulate his senses by either speaking to the patient by calling out his name in a loud voice or shaking the patient gently as if rousing the patient from sleep. If there is no response to these stimuli, then assess the patient for stupor or coma. Coma is a term, describing a state in which the patient's response to external stimuli or inner needs is grossly impaired. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is used to assign a numerical value to the patient's responses to defined stimuli. It is particularly useful for quantifying changes in conscious level over time. Stupor is described as a state where the patient, although inaccessible, shows some response to painful stimuli. POSTURE AND MOTOR BEHAVIOR – Note body posture and the patient’s ability to relax. Observe the pace, range, and character of movements. Do they seem to be under voluntary control? Are certain parts immobile? Does the patient lie in bed, or prefer to walk about? DRESSING, GROOMING AND PERSONAL HYGIENE – Note the patient’s clothes, hair, nails, teeth, skin, beard, etc. How is the patient groomed? How does the person’s grooming and hygiene be compared with those of people of comparable age, lifestyle, and socioeconomic group? FACIAL EXPRESSION – Observe the face while the patient rests and when the patient is interacting with others. Watch for variations in expression. Are they appropriate? Or is the face relatively immobile throughout? MANNER, AFFECT, AND RELATIONSHIP TO PERSONS AND THINGS – Using your observations of facial expressions, voice and body movements, assess the patient’s affect. Is the affect labile, blunted, or flat? Does it seem inappropriate or extreme at certain points? If it is inappropriate then, how is it so? Note the patient’s openness, approachability, and reactions to others around and to that of the surroundings. Does the patient seem to hear or see things that you do not or seem to be conversing with someone who is not there? SPEECH AND LANGUAGE: Throughout the interview, note the characteristics of the patient’s speech, with respect to the following: QUANTITY – Is the patient talkative or relatively silent? Are his comments spontaneous or only responsive to direct questions? RATE – Is speech fast or slow? LOUDNESS – Is speech loud or soft? ARTICULATION OF WORDS – Are the words spoken clearly and distinctly? Is there a nasal quality to the speech? FLUENCY – This involves the rate, flow, and melody of speech and the content and use of words. Be alert for abnormalities of spontaneous speech such as: Hesitancies and gaps in the flow and rhythm of words. Disturbed inflections, such as a monotone. Circumlocutions, in which phrases or sentences are substituted for a word the person cannot think of, such as “what you read” for “book”. Paraphasias, in which words are malformed (“I read a cook”), wrong (“I read a back”), or invented (“I write with a dack”). It becomes obvious while talking with the patient, whether or not there is a major communication problem, and whether this is dysphasia (speech language problem), dysarthria (speech articulation problem) or dysphonia (impaired control of air flow). Ask the patient to recite the months of the year. If this simple request is not understood, it is likely there is a major dysphasia or cognitive problem. The large number of long words in the months, with their simple meaning, allows easy detection of a dysarthria or dysphonia. MOOD: Moods include sadness and deep melancholy; contentment, joy, euphoria, and elation; anger and rage; anxiety and worry; and detachment and indifference. Find out about the patient’s usual mood level and how it has varied with life events. The reports of relatives and friends may be of a great value. Ask for the questions like - What has the patient’s mood been like? How intense has it been? Has it been labile or fairly unchanging? How long has it lasted? Is it appropriate to the patient’s circumstances? In case of depression, have there also been episodes of an elevated mood (suggesting a bipolar disorder)? In case of suspected depression, assess its depth and any associated risk of suicide. THOUGHT AND PERCEPTIONS: THOUGHT PROCESSES Assess the aspects like logic, relevance, organization, and coherence of the patient’s thought processes in his words and speech throughout the interview. Listen for patterns of speech that suggest disorders of thought processes. THOUGHT CONTENT You may follow appropriate leads as they occur rather than using preformed lists of specific questions to assess the patient’s thought content. You may need to make more specific inquiries. If so, couch them in tactful and accepting terms. Abnormalities in thought content include compulsions, obsessions, phobias, anxieties, feeling of unreality, feeling of depersonalization, delusions, illusions, hallucinations, etc. COGNITIVE FUNCTIONS: ORIENTATION – You can ask for specific dates and times, the patient’s address and telephone number, the names of family members, or the route taken to the hospital. In either of these ways, determine the patient’s orientation for the following: Time (the time of day, day of the week, month, season, date and year) Place (the patient’s residence, the names of the hospital, city, and state) Person (the patient’s own name, the names of relatives and professional personnel) COGNITIVE FUNCTIONS: MEMORY – Inquiry must be done with regards to remote as well as recent memory. For remote memory, inquire about birthdays, anniversaries, social security number, names of schools attended, jobs held, or past historical events relevant to the patient’s past. For recent memory testing, ask the patient about the day’s weather, today’s appointment time, medications or laboratory tests taken during the day. Ask questions with answers that you can check against other sources so that you will know whether or not the patient is confabulating. Memory deficits often relate to temporal lobe disease and are at times modality specific. Verbal memory is more impaired in dominant temporal disease and visual memory is impaired in non-dominant hemisphere disease. Bilateral mesial temporal lobe damage leads to memory loss, visual agnosia for objects, a tendency to explore objects by putting them in the mouth, indiscriminate sexual behavior, especially to inanimate objects, and a flat affect (Kluver-Bucy syndrome), illustrating the importance of the temporal lobes in memory, language function and emotional behavior. VOCABULARY – Information and vocabulary, when observed clinically, provide a rough estimate of a person’s intelligence. Note the person’s grasp of information, the complexity of the ideas expressed, and the vocabulary used. More directly, you can ask about specific facts. These aspects are relatively unaffected by any but the most severe psychiatric disorders, and may be helpful for distinguishing mentally retarded adults (whose information and vocabulary are limited) from those with mild or moderate dementia (whose information and vocabulary are fairly well preserved). CALCULATING ABILITY – Test the patient’s ability to do arithmetical calculations, starting at the rote level with simple addition and multiplications. Poor performance may be a useful sign of dementia or may accompany aphasia, but it must be assessed in terms of the patient’s intelligence and education. EXAMINATION OF CRANIAL NERVES: Top EXAMINATION OF CRANIAL NERVE I – OLFACTORY NERVE: Testing of the sense of smell can be carried out by presenting the patient with familiar and nonirritating odors. A prior examination of each nasal passage should be done to check if it is open by compressing one side of the nose and asking the patient to sniff through the other. The patient should then close both eyes. Occlude one nostril and test smell in the other with substances like cloves, coffee, soap, or vanilla. Ask if the patient smells anything and, if so, what. Test the other side. A person should normally perceive odor on each side, and can often identify it. Loss of smell may occur as a result of nasal diseases, head trauma, smoking, aging, local diseases of the cribriform plate, sub-arachnoid haemmorrhage, neoplastic tumors in olfactory groove or frontal lobe, tabes dorsalis, meningitis, Refsum’s disease, Paget’s disease, hypoparathyroidism, Zinc deficiency, abuse of cocaine, hysteria and idiopathic. It may also be congenital. Paraosmia (perversion of smell) and cacosmia (Unpleasant odours) are rare phenomena and may be seen following head injury or some psychiatric illnesses. EXAMINATION OF CRANIAL NERVE II – OPTIC NERVE: Examination of the optic nerve can be carried out under the following headings: Acuity of vision Field of vision Colour vision Pupillary reflexes ACUITY OF VISION – The visual acuity of each should be tested separately for near and distant vision. Formal testing ideally involves a Snellen’s chart held 6 m from the patient, examining each eye in turn. Acuity better than 6/60 is dependent on central (macular) vision. Visual acuity for near vision is tested by Jaeger’s chart where in the test types are of varying sizes. Acuity can be examined at bed-side with finger counting at a distance of 1 meter. Visual acuity is most commonly impaired in conditions with compressive and noncompressive lesions of the optic nerve. VISUAL FIELDS – The visual field is the whole extent of the field of vision in each eye. It can be tested as follows: Moving finger test. Sit or stand in front of the patient. The patient covers one eye and fixes his gaze on your eye. Bring your wiggling finger slowly into view from out of the patient's view. The finger should be kept more than mid-way between you and the patient. Each of the upper temporal, lower temporal, upper nasal and lower nasal quadrants of the visual field are tested separately. This test sensitively detects mild partial temporal field defects, such as would result from a pituitary tumour slowly growing into the optic chiasm and affecting the crossing temporal field fibres. Red pin confrontation test. This test uses a large red hatpin, held equidistant between yourself and the patient, using exactly the same conditions as above. The patient again covers the eye not to be tested, while you face them about 1.5m away and cover your own eye. Determine the field limit by checking whether you and the patient see the pin at the same time. This test is accurate in detecting paracentral scotomas or paracentral colour desaturation in optic neuritis, and for comparing the size of the patient's blind spot with your own. Visual field defects include Type Meaning Conditions of occurrence Concentric diminution Vision restricted all around the periphery. Hysteria, Papilledema, retinal lesions Central Scotoma Vision lost in the centre of the visual field. Optic neuritis, retrobulbar neuritis, pressure on optic nerves, choroidal macular lesion Hemianopia Vision is lost in one half of the visual field. Homonymous – Blindness in one half of both sides of the eyes. Quadrantic – Blindness in quarter of the normal visual field. Bi-temporal – Blindness in temporal halves of both the fields. Bi-nasal – Blindness in the nasal halves of both the fields. Homonymous – Lesions of the optic tract or radiations on the opposite side. Quadrantic – Partial lesions of the optic radiations, lesions of the occipital lobes. Bi-temporal – lesion of nasal halves of both the optic nerves, pituitary tumors. Bi-nasal – Lesions of uncrossed optic fibres of both the fields. COLOR VISION – This is tested using coloured plates that have patterns of coloured spots, some forming numbers and others a random background. It can also be tested by using pseudoisochromatic plates of Ishihara. Colour vision is mainly confined to the macular field; acquired abnormalities in colour vision are therefore a sensitive test for optic neuritis and certain retinal diseases. Also, patients with bilateral lesions of infero-medial occipital region have colour blindness. EXAMINATION OF PUPILS – Pupils must be examined and compared for their size, shape and mobility. LIGHT REFLEX: On shining a powerful light beam into one or both the eyes, the pupils of both the eyes immediately contract. It is tested by shielding one eye and a bright beam is thrown into another eye. The beam must be brought from the side onto the patient. A brisk contraction of pupil will be observed as a response. Consensual light reflex demonstrates constriction of the pupils of both the eyes when the light is thrown on only one eye. In lesion of optic nerve there will be no constriction of pupils on both the sides. In lesion of III cranial nerve the reflex is absent only on that side, when light is shown, in either yes sensory arc is intact in both the eyes. ACCOMMODATION REFLEX: It is tested by asking the patient to look at a distance and then fix his eyes either on the tip of the nose or on the examiners fingers which are brought about 9 inches in the front of the bridge of the nose. It is affected or lost in midbrain lesions. EXAMINATION OF CRANIAL NERVES III, IV AND VI – OCULOMOTOR, TROCHLEAR AND ABDUCENS It includes: Examination of eye balls Examination of light reflex Examination of the reaction to accommodation MOVEMENTS OF THE EYE BALLS – Movements of the eye balls are tested in all directions with the help of index finger being moved in various directions. Hold each deviation for atleast 5 seconds. Examiners finger must be kept at a distance of 12 inches from the patient’s eyes. Care must be taken that the patient’s head remains fixed while carrying out the test to ensure movements carried out by the eye balls only. For this the physician may use his left hand to hold the patient’s head and fix it. Observe for the following: Ptosis Lagging of one or either eye Squint/ Strabismus Nystagmus Inability to move the eye balls outwards indicates VI nerve palsy. Inability to move the eye balls upwards and medially, indicate III nerve palsy. A slight difference in the width of the palpebral fissures may be noted in about one third of all normal people. EXAMINATION OF CRANIAL NERVE V – FACIAL NERVE: SENSORY EXAMINATION – Sensation in the face is best tested using a pin. Test for each of the three divisions separately, checking for symmetry of perceived pinprick intensity of the two sides. The patient’s eyes should be closed. If there is reduced sensation, delineate its extent by testing from a normal to an abnormal area. Patients with trigeminal pain, e.g. trigeminal neuralgia, will be reluctant to allow sensory testing. If you find an abnormality, confirm it by testing temperature sensation. Two test tubes, filled with hot and ice-cold water, are used as stimuli. A tuning fork may also be used. It usually feels cool. Touch the skin and ask the patient to identify “hot” or “cold.” The corneal reflexes should be tested by touching a wisp of cotton wool on the corneal surface at its margin with the conjunctiva. This is usually quite unpleasant for the patient. There should be a brisk bilateral blink response. Unilateral decrease in or loss of facial sensation suggests a lesion of Trigeminal nerve or of interconnecting higher sensory pathways. MOTOR EXAMINATION – While palpating the temporal and masseter muscles in turn, ask the patient to clench his or her teeth. Note the strength of muscle contraction. Weak or absent contraction of the temporal and masseter muscles on one side suggests a lesion of this nerve. Bilateral weakness may result from peripheral or central involvement. Test the pterygoid muscles by forceful opening of the jaw against resistance: with unilateral lateral pterygoid weakness the jaw deviates to the ipsilateral side as it opens. The jaw jerk is a fifth-nerve stretch reflex. The reflex is increased in corticobulbar tract disease. EXAMINATION OF CRANIAL NERVE VII – FACIAL NERVE: Inspect the face, both at rest and during conversation with the patient. Note any asymmetry (e.g., of the naso-labial folds), and observe for any tics or abnormal movements. Ask the patient to carry out the following activities and note for any weakness or asymmetry: Raise both eyebrows. Frown. Close both eyes tightly so that you cannot open them. Test muscular strength by trying to open them. Show both upper and lower teeth. Smile. Puff out both cheeks. In unilateral facial paralysis, the mouth droops on the affected side when the patient smiles or grimaces. Flattening of the naso-labial fold and drooping of the lower eyelid suggest facial weakness. A peripheral injury to Facial nerve, as in Bell’s palsy, affects both the upper and the lower face; a central lesion affects mainly the lower face. ASSESSMENT OF TASTE – Test the sense of taste using strong solutions of sugar and common salt, and weak solutions of citric acid and quinine, as tests for 'sweet', 'salty', 'sour' and 'bitter' respectively. Apply these solutions to the surface of the protruded tongue with a small swab on a spatula. The patient should be asked to indicate perception of the taste before the tongue is withdrawn in order to decide whether taste is disturbed anteriorly or posteriorly. After each test the mouth must be rinsed. The bitter quinine test should be applied last, as its effect is more lasting than that of the others. Positive taste symptoms, e.g. taste hallucinations, may constitute the aura of temporal lobe epilepsy. EXAMINATION OF CRANIAL NERVE VIII – AUDITORY NERVE: Assess hearing. If hearing loss is present, test for lateralization, and compare air and bone conduction. AIR AND BONE CONDUCTION – If hearing is diminished, try to distinguish between conductive and sensorineural hearing loss. You need a quiet room and a tuning fork, preferably of 512 Hz or possibly 1024 Hz. These frequencies fall within the range of human speech (300 Hz to 3000 Hz). Set the fork into light vibration by briskly stroking it between thumb and index finger or by tapping it on your knuckles. TEST FOR LATERALIZATION (WEBER TEST). Place the base of the lightly vibrating tuning fork firmly on top of the patient’s head or on the mid-forehead. Ask where the patient hears it: on one or both sides. Normally the sound is heard in the midline or equally in both ears. If nothing is heard, try again, pressing the fork more firmly on the head. COMPARE AIR CONDUCTION (AC) AND BONE CONDUCTION (BC) (RINNE’S TEST). Place the base of a lightly vibrating tuning fork on the mastoid bone, behind the ear and level it with the canal. When the patient can no longer hear the sound, quickly place the fork close to the ear canal and ascertain whether the sound can be heard again. Here the “U” of the fork should face forward, thus maximizing its sound for the patient. Normally the sound is heard longer through air than through bone (AC > BC). In unilateral conductive hearing loss, sound is lateralized to the impaired ear. It occurs in conditions like Acute otitis media, Perforation of the eardrum, Obstruction of the ear canal Cerumen. In unilateral sensorineural hearing loss, sound is heard in the good ear. In conductive hearing loss, sound is heard through bone as long as or longer than it is through air (BC = AC or BC > AC). In sensorineural hearing loss, sound is heard longer through air (AC > BC). EXAMINATION OF CRANIAL NERVE IX – GLOSSOPHARYNGEAL NERVE: The glossopharyngeal nerve is rarely damaged alone. Examine the following: Test for Taste sensation on the posterior part of the tongue. Elicit pharyngeal reflex contraction after tickling the back of the pharynx with a small cotton-covered stick. A response of posterior pharyngeal wall contraction is normally observed. Unilateral absence of this reflex suggests a lesion of CN IX. EXAMINATION OF CRANIAL NERVE X – VAGUS NERVE: EXAMINATION OF PALATE: Nasal regurgitation. Weakness of the soft palate leads to failure of palatal elevation, failure of closure of the nasopharynx and nasal regurgitation of fluids during swallowing. Palatal dysarthria. The patient cannot pronounce words requiring complete closure of the nasopharynx, e.g. 'egg' pronounced as 'eng'. In unilateral paralysis these symptoms are less obvious. Palatal elevation. Ask the patient to open the mouth and say 'aah'. Use a tongue depressor to obtain a good view of the soft palate and uvula. Unilateral paralysis results in elevation only of the normal side and deviation of the uvula towards the normal side. In a UMN lesion the palate may be tonically elevated more on the affected side and may move less on phonation. EXAMINATION OF LARYNX Check for hoarseness of voice. Unilateral damage to the superior laryngeal branch of the vagus nerve is usually symptomless, but bilateral involvement causes paralysis of the cricopharyngeus. This reduces tension on the vocal cords, preventing singing or speaking higher notes. Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy causes vocal cord paralysis; there is inability to phonate normally (a 'breathy voice'), and the cough is loose and 'bovine' because the vocal cords cannot properly come together to seal off the airway. In bilateral paralysis these features are much more pronounced; the paralysed cords tend to lie in an adducted position and there is a risk of stridor and respiratory obstruction. Breathing is noisy and partially obstructed. EXAMINATION OF CRANIAL NERVE XI – SPINAL ACCESSORY NERVE: EXAMINE THE UPPER TRAPEZIUS MUSCLE FIBRES: Ask the patient to shrug their shoulders while you press downward on them. The shrug may be weak on the affected side. EXAMINE THE STERNOMASTOID MUSCLE: Ask the patient to turn the head while you resist with a hand on the side of the face. Observe the contraction of the activated sternomastoid muscle on the side opposite to the direction of movement. In weakness of sternomastoid the patient is unable to turn his head to the opposite side. EXAMINATION OF CRANIAL NERVE XII – HYPOGLOSSAL NERVE: Listen to the articulation of the patient’s words. Inspect the patient’s tongue as it lies on the floor of the mouth. Look for any atrophy or fasciculations (fine, flickering, irregular movements in small groups of muscle fibers). Some coarser restless movements are often seen in a normal tongue. Then, with the patient’s tongue protruded, look for asymmetry, atrophy, or deviation from the midline. Ask the patient to move the tongue from side to side, and note the symmetry of the movement. In ambiguous cases, ask the patient to push the tongue against the inside of each cheek and in turn you can palpate externally for its strength. Following abnormalities can be diagnosed by observing the tongue movements: Tongue condition/Movement type Associated Diseases Wasting and fasciculation in a relaxed tongue Lower motor neuron lesion involving nucleus and nerve Small pointed stiff tongue Upper motor neuron lesion Bilateral fasciculation Motor neuron disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Unilateral wasting fasciculation Skull base tumors Tremors of tongue Parkinson’s disease EXAMINATION OF THE MOTOR SYSTEM: Examination of motor system includes the following: Inspection Palpation Tone Power Reflexes Coordination Posture and abnormal movements Stance and gait INSPECTION: Observe the patient’s body position during movement and at rest. Note the size of the muscles in all four limbs and compare them on both the sides. Note for any wasting or hypertrophy. PALPATION: One can confirm the inspection findings by palpating the muscles and measuring their bulk by measuring their respective limb circumferences. Generally, nutrition of the muscle is judged by noting the circumference of extremities at the level where maximum muscle mass is present. Compare the measurements of both the sides. Muscular atrophy refers to a loss of muscle bulk (wasting). It occurs in diseases like Diabetic neuropathy Motor neuron diseases Disuse of the muscles Rheumatoid arthritis Protein-calorie malnutrition. Hypertrophy refers to an increase in bulk with proportionate strength, while increased bulk with diminished strength is called pseudohypertrophy (as in Duchenne muscular dystrophy). TONE: When a normal muscle with an intact nerve supply is relaxed voluntarily, it maintains a slight residual tension known as muscle tone. This can be assessed by feeling the muscle’s resistance to a passive stretch. Complete relaxation is important. Take one hand with yours and, while supporting the elbow, flex and extend the patient’s fingers, wrist, and elbow, and put the shoulder through a moderate range of motion. On each side, note muscle tone, i.e. the resistance offered to your movements, the degree of movement and the range of movement. Tone must be tested for upper extremity as well as the lower extremity. Decreased resistance suggests Disease of the peripheral nervous system Cerebellar disease Acute stages of spinal cord injury Marked floppiness indicates hypotonic or flaccid muscles. Increased resistance that varies, commonly worse at the extremes of the range, is called spasticity. Resistance that persists throughout the range and in both directions is called leadpipe rigidity. POWER: The strength of individual muscle groups is tested by comparing them with the examiner's own strength or by comparison with what the examiner judges to be normal. Grades of Power Muscle Movement Grade 0 Complete paralysis Grade 1 A flicker of contraction only Grade 2 Power detectable only when gravity is excluded by appropriate postural adjustment. Grade 3 The limb can be held against the force of gravity, but not against the examiner's resistance. Grade 4 The limb can be held against gravity and against some resistance, but is not normal. Grade 5 The limb can be held against gravity and normal resistance. Normal power. REFLEXES: Reflex is an involuntary response to an adequate sensory stimulus. They are classified into two types as: Superficial Reflexes Deep Reflexes SUPERFICIAL REFLEXES – These are polysynaptic reflexes elicited in response to cutaneous stimuli. They do not depend on muscle stretch receptors. The abdominal and plantar reflexes are particularly important. Corneal and palatal reflexes. See Cranial nerves, above. Scapular reflex (C5-T1). Stroke the skin between the scapulae. The scapular muscles contract. Superficial abdominal reflexes (T7-12). The patient lies relaxed and in supine position, with the abdomen uncovered. A thin wooden stick or the reverse end of the tendon hammer is dragged quickly and lightly across the abdominal skin in a dermatomal plane from the loin towards the midline. A ripple of contraction of the underlying abdominal muscles follows the stimulus. Abdominal reflexes are absent in UMN lesions above their spinal level, as well as in lesions of the local segmental thoracic root or the spinal cord. Abdominal reflexes are difficult to elicit in obese or multiparous women. An anxious patient will have brisk abdominal reflexes as well as brisk tendon reflexes. Cremasteric reflex (L1/2). Stroke the skin at the upper inner part of the thigh. In response the testicle moves upwards on the side of stimulation. The plantar reflex (L5, S1). The muscles of the lower limb should be relaxed. The outer edge of the sole of the foot is stimulated by firmly scratching a key or a stick along it from the heel towards the little toe. The normal response is plantar flexion of the toes. The plantar reflex is important in identifying a UMN lesion. Abnormal response observed called Babinski’s sign shows dorsiflexion of great toe and fanning of other toes. Conjunctival Reflex. Touch the conjunctiva with a wisp of cotton wool. In response, blinking of the eyes is observed. Pupillary Reflex. See Cranial nerve examination. DEEP REFLEXES – When the tendon of a partially stretched muscle is struck a single sharp blow with a soft rubber hammer, thereby, suddenly stretching the muscle, the muscle contracts briefly. This is called the deep tendon reflex, or the monosynaptic stretch reflex. To elicit a deep tendon reflex, persuade the patient to relax, position the limbs properly and symmetrically, and strike the tendon briskly, using a rapid wrist movement. The briskness of deep tendon reflexes varies according to the individual and can sometimes only be elicited in normal individuals by applying reinforcement. Ask the patient to make a strong voluntary muscular effort, e.g. hooking the fingers of the two hands together and then pulling them against one another as hard as possible, making a fist with one hand, or clenching the teeth. Compare each reflex side to side. Grade tendon reflexes as follows: 0 Absent 1 Present (as a normal ankle jerk) 2 Brisk (as a normal knee jerk) 3 Very brisk 4 Clonus Various Deep Reflexes: Jaw jerk. Ask the patient to keep the mouth slightly open and keep your keep your finger over the chin. Strike the finger over the chin with the hammer. A normal response observed is closure of the jaw. Biceps jerk C5, C6. Flex the patient's elbow to almost a right-angle with the forearm in semi-prone position. With your index finger on the biceps tendon, strike it firmly with the patellar hammer. The biceps contracts in response resulting in flexion of the elbow. Supinator jerk C5, C6. A blow on the styloid process of the radius stretches the supinator, causing supination of the forearm. The patient's elbow should be slightly flexed and slightly pronated, in order to avoid contraction of brachioradialis. With midcervical lesions (cervical myelopathy) the supinator or bicep jerks may be absent but brisk flexion of the fingers may occur instead. This is inversion of the reflex and suggests hyperexcitability of anterior horn cells below the affected level. Triceps jerk C6, C7. Flex the patient's elbow with the forearm resting across the chest or in their lap. Tap the triceps tendon just above the olecranon process. The triceps contracts resulting in extension of the elbow. Knee jerk L2, L3, L4. With the patient supine, pass your hand under the knee to be tested so that it supports the relaxed leg with the knee flexed at a little less than 90°. Strike the patellar tendon midway between its origin and its insertion. Look for a contraction of the quadriceps resulting in extension of the knees. Ankle jerk S1, S2. Slightly dorsiflex the ankle so as to stretch the Achilles tendon and, with your other hand, strike the tendon on its posterior surface, or on the sole of the foot. A quick contraction of the calf muscles results in plantar flexion of the foot. CO-ORDINATION: It is the co-operation of separate muscles or group of muscles in order to accomplish a definite act. TESTING COORDINATION IN THE UPPER LIMBS – Finger-nose test: Ask the patient to touch the point of the nose and then the tip of your finger, held at arm's length in front of the patient's face, using their index finger. Ask the patient to repeat the test with the eyes closed; any additional irregularity suggests impairment of position sense in the limb. Dysdiadochokinesis: Ask the patient to tap your palm with the tips of the fingers of one hand, alternately in pronation and supination, as fast as possible. Minor degrees of inco-ordination can be both felt and heard. All normal people can do this very rapidly, but usually slightly less rapidly with the non-dominant than with the dominant hand. Dysdiadochokinetic movements are slowed, irregular, incomplete, and may be impossible. Parkinsonism may also impair rapid movements, with slowing, reduced amplitude and prominent fatigue, but without irregularity. TESTING CO-ORDINATION IN LOWER LIMBS – Tandem Walk: Ask the patient to walk along a straight line. Heel-shin test: While the patient is lying supine on the couch, ask them to lift one leg and then to bend the knee, place the heel on the opposite knee and slide this heel down the shin towards the ankle under visual guidance. In cerebellar ataxia, a characteristic, irregular, side-to-side series of errors in the speed and direction of movement occurs. Also, watch the patient draw a large circle in the air with the toe. The circle should be drawn smoothly and accurately, but in ataxia it is 'squared off' irregularly. Romberg’s Test: Ask the patient to stand with his feet close together with his eyes open and then with his eyes closed. If the patient sways or falls the Romberg’s test is positive and co-ordination is absent. POSTURE AND ABNORMAL MOVEMENTS: Postural control of the upper limbs is assessed by asking the patient to hold the arms outstretched with the eyes closed. Posture of the trunk and lower limbs is assessed separately with gait. Pyramidal drift describes a tendency for the hand to move upward and supinate if the hands are held outstretched in a pronated position (palms downward), or to pronate downward if the hands are held in supination. Cerebellar drift is generally upward, with excessive rebound movements if the hand is suddenly displaced downward by the examiner. Parietal drift is an outward movement on displacing the ulnar border of the supinated hand. Observation must be done to identify any abnormal movements. They involve involuntary muscle contractions of various types. Rest tremor occurs in Parkinson's disease and is typically a 'pill-rolling' tremor of one or both hands, where the thumb is moved repetitively back and forth across the tips of the fingers. Postural tremor or essential tremor is a relatively symmetrical tremor and involves the upper limbs more than the legs. It may also affect the head and tongue. A typical parkinsonian tremor may also be worse during posture. Postural tremor also typifies adrenergic tremors, e.g. physiological or anxiety tremor and thyrotoxicosis. Tremor may also occur in sensory ataxic neuropathy. Action tremor, a terminal tremor in which the finger overshoots and oscillates when approaching a visual target, is indicative of cerebellar ataxia or sensory ataxia. Hysterical tremor tends to involve a limb or the whole body, to occur at rest and be fast and violent. During distraction by the examiner it disappears. Rubral tremor is unilateral or bilateral and occurs in rest, posture and action, sometimes building up over a few seconds of posture. It reflects brainstem disease, including paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis. Pseudoathetosis describes fidgety movements of the fingers when in posture with the eyes closed and is due to a proprioceptive deficit, including a large fibre sensory neuropathy or a lesion of the nucleus cuneatus at the synaptic termination of the dorsal columns, e.g. from foramen magnum stenosis. Similar small finger movements can be the result of fasciculatory contractions of pathologically large motor units in motor neuron disease. Myoclonus is involuntary jerky movement of a body part or parts, or sometimes of the whole body. When rhythmic, it may appear as a rest or action tremor. Its origin can be cortical, e.g. focal epilepsy or, if ongoing, epilepsia partialis continua. Myoclonus of body segments is usually spinal in origin, whereas that of the whole body usually originates in the brainstem and can occur normally on falling asleep, or pathologically as an exaggerated startle or shivering response or as part of a generalized epileptiform disorder. When a muscle is voluntarily tonically activated, brief myoclonic relaxation may interrupt the activation. This is called negative myoclonus. An example is asterixis of liver disease, in which maintained wrist extension is irregularly interrupted, producing a 'flapping' motion. Rarely, negative myoclonus in the quadriceps muscles while standing may result in collapse. Chorea is a translation of the word 'dance', which accurately portrays its fidgety, fluid, random and semipurposeful quality. The involuntary movements tend to embellish voluntary movements, such as walking, or picking up a cup and saucer. Voluntary actions are performed surprisingly well despite the constant interruption. Its causes include Huntington's disease, Sydenham's chorea, lupus and pregnancy, and it may also occur idiopathically in the elderly. Finally, chorea and other involuntary movements may arise as side effects of dopaminergic or antidopaminergic drugs; in this context the involuntary movement is termed dyskinesia. Ballism is a violent movement of the proximal limb and trunk. Hemiballismus (unilateral ballism) is almost always due to a stroke affecting the contralateral subthalamic nucleus in the midbrain. Athetosis is a complex, writhing involuntary movement, usually more pronounced in distal than in proximal muscles and of lower amplitude than chorea. Dystonia describes any abnormal posturing of the body. Its origin may be symptomatic of underlying disease, such as cerebral palsy, pyramidal lesions or generalized inherited or metabolic extrapyramidal diseases. Often, however, dystonia is idiopathic, probably inherited, generalized, limited to particular body segments (e.g. torticollis), or focal and perhaps task specific (e.g. writers' cramp or musician's dystonia). Tics are simple, normal movements that become repeated unnecessarily to the point where they become an embarrassment. They often occur in the context of psychiatric disorders. In contrast to other involuntary movement disorders they can be readily imitated and voluntarily suppressed, albeit briefly. Head nodding and facial twitching are common examples. In Tourette's syndrome tics manifest as embarrassing scatological vocalizations. Tetany is due to hypocalcaemia or alkalosis. There is a characteristic cramped posture of the affected hand so that fingers and thumb are held stiffly adducted and the hand partially flexed at the metacarpophalangeal joints; the toes may be similarly affected (carpopedal spasm). Ischaemia of the affected limb, produced by a sphygmomanometer cuff inflated above the arterial pressure for 2 or 3 minutes, will augment this sign or produce it if it is not already present (Trousseau's sign). Another useful test is to tap lightly with a patellar hammer at the exit of the facial nerve from the skull, about 3-5cm below and in front of the ear. The facial muscles twitch briefly with each tap (Chvostek's sign). Cramp is a spontaneous contraction of part or the whole of a muscle. It is common in healthy people, especially in the calf, and may occur with neurogenic muscle weakness. Other causes of cramp include motor neuron disease or metabolic disorders, e.g. hyponatraemia and hypomagnesaemia. Poor relaxation of muscle, myotonia, is a feature of primary muscle disease due to abnormal ion transport across the muscle cell membrane, often as the result of a genetic channelopathy such as congenital myotonia, paramyotonia or myotonic dystrophy. Myotonia in some types of hereditary muscle channelopathy is worsened in the cold or induced by active contraction, such as hand gripping; the patient is unable to let go again immediately. Similar difficulty in opening the eyes occurs after forceful closure. Percussion myotonia is an enhanced myotatic response elicited by tapping the thenar eminence or the surface of the tongue. Neuromyotonia is a continuous muscular activity caused by dysfunction in nerve fibres; as part of a generalized acquired neuropathy it is called Isaac's syndrome. STANCE AND GAIT: STANCE: The following two tests can often be performed concurrently. They differ only in the patient’s arm position and in what you are looking for. In each case, stand close enough to the patient to prevent a fall. The Romberg test: Refer Co-ordination in lower limbs. Test for pronator drift: The patient should stand for 20 to 30 seconds with both arms straight forward, palms up, and with eyes closed. A person who cannot stand may be tested for a pronator drift in the sitting position. In either case, a normal person can hold this arm position well. Now, instructing the patient to keep the arms up and eyes shut, tap the arms briskly downward. The arms normally return smoothly to the horizontal position. This response requires muscular strength, coordination, and a good sense of position. The pronation of one forearm suggests a contralateral lesion in the corticospinal tract; downward drift of the arm along with flexion of fingers and elbow may also occur. These movements are called a pronator drift. GAIT: Ask the patient to do various lower limb movements like walking, tandem walk, walk on the toes, hop, etc. A gait that lacks coordination, with reeling and instability, is called ataxic. Ataxia may be due to cerebellar disease, loss of position sense, or intoxication. Tandem walking may reveal an ataxia not previously obvious. Walking on toes and heels may reveal distal muscular weakness in the legs. Inability to heel-walk is a sensitive test for corticospinal tract weakness. Difficulty with hopping may be due to weakness, lack of position sense, or cerebellar dysfunction. EXAMINATION OF THE SENSORY SYSTEM: Top In carrying out sensory testing, the examiner must be aware of the entire dermatomal and peripheral nerve distribution of sensations in the body. This knowledge is necessary to appreciate that a certain distribution of abnormal sensation results from a lesion of a particular peripheral nerve, nerve root or at the spinal segmental level. To evaluate the sensory system, following sensation types need to be tested: Pain and temperature Position and vibration Light touch Discriminative sensations While carrying out the examination, Compare symmetric areas on the two sides of the body, including the arms, legs, and trunk. Before each test, show the patient what you plan to do and how would you do it. The patient’s eyes should be closed during actual testing, unless specified. PAIN: Use a sharp pin or other suitable tool. Occasionally, substitute the blunt end for the pointed one. Ask the patient to identify if it is sharp or blunt. When comparing ask the patient if he feels the same sensation on both the sides. Apply the lightest pressure needed for the stimulus to feel sharp. Specific terms are used to describe various positive and negative pain symptoms and signs: Analgesia - the absence of sensibility to pain Hypoalgesia - reduced pain sensibility Hyperalgesia - an increased pain sensibility to mildly painful stimuli Allodynia - pain perception from a normally non-painful stimulus Hyperpathia - pain perception that spreads out from the point of the stimulus or outlasts the stimulus in time Paraesthesiae - tingling sensations sometimes so intense as to be painful, occurring spontaneously or in response to light cutaneous stimuli. TEMPERATURE: Use two test tubes, filled with hot and cold water, or a tuning fork heated or cooled by water. Touch the skin and ask the patient to identify if he feels hot or cold. LIGHT TOUCH: With a fine wisp of cotton, touch the skin lightly, avoiding pressure. Ask the patient to respond whenever a touch is felt, and compare sensation felt in one area with the another. VIBRATION: Use a relatively low-pitched tuning fork of 128 Hz. Tap it on the heel of your hand and place it firmly over a distal interphalangeal joint of the patient’s finger and then over the interphalangeal joint of the big toe. Ask what the patient feels. If you are uncertain whether it is pressure or vibration, ask the patient to tell you when the vibration stops, and then touch the fork to stop it. If vibration sense is impaired, proceed to more proximal bony prominences like wrist, elbow, anterior superior iliac spine, clavicle, etc. POSITION: Grasp the patient’s big toe, holding it by its sides between your thumb and index finger, and then pull it away from the other toes so as to avoid friction. Demonstrate “up” and “down” as you move the patient’s toe clearly upward and downward. Then, with the patient’s eyes closed, ask for a response of “up” or “down” when moving the toe in a small arc. Repeat several times on each side, avoiding simple alternation of the stimuli. If position sense is impaired, move proximally to test it at the ankle joint. In a similar fashion, test position in the fingers. Loss of position sense, like loss of vibration sense, suggests either posterior column disease or a lesion of the peripheral nerve or root. DISCRIMINATIVE SENSATIONS: As discriminative sensations are dependent on touch and position sense, they are useful only when these sensations are either intact or only slightly impaired. The patient’s eyes should be closed during all these tests. STEREOGNOSIS – Stereognosis refers to the ability to identify an object by feeling it. Place a familiar object such as a coin, paper clip, key, pencil, or cotton ball in the patient’s hand and ask the patient to identify it. Normally a patient will identify it correctly. Asking the patient to distinguish “heads” from “tails” on a coin is a sensitive test of stereognosis. Astereognosis refers to the inability to recognize objects placed in the hand. TWO-POINT DISCRIMINATION – Using the two ends of an opened paper clip, or the sides of two pins, touch a finger pad in two places simultaneously. Alternate the double stimulus irregularly with a one-point touch. Be careful not to cause pain. Find the minimal distance at which the patient can discriminate one from two points (normally less than 5 mm on the finger pads). Lesions of the sensory cortex increase the distance between two recognizable points. POINT LOCALIZATION – Briefly touch a point on the patient’s skin. Then ask the patient to open both eyes and point to the place touched. Normally a person can do so accurately. Lesions of the sensory cortex impair the ability to localize points accurately. Top DR.AR WADGAONKAR,PSPMMHMC,SOLAPUR