How to Lose Weight

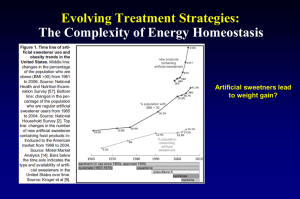

•

•

•

•

•

How many more calories a day

does the average American eat

today compared to someone in

1970

A. 200

B. 300

C. 400

D. 500

E. 523

Answer

• E. 523

What has changed to increase the

calories?

Answer

• Larger portions

• Increased processed fats and sugars

Can Physicians make

interventions that are meaningful

for weight loss, control of BP, BS

and Cholesterol in routine

clinical practice?

Reducing Blood Pressure Levels Effectively in Practice

•

•

•

Two interventions each helped to modify this cardiovascular risk factor

successfully, but staffing such programs would be costly.

Practice guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease identify clear

targets for risk-factor modification but often say little about the difficult

objective of actually achieving them. Now, we have data on two strategies

specifically designed to help patients with uncontrolled CVD risk factors reach

their prevention goals.

In one study from a California county health system, researchers enrolled 419

low-income patients (mean age, 55; 66% women; 85% nonwhite) who had at

least moderately uncontrolled, modifiable CVD risk factors. Participants (19%

with established CVD, 63% with diabetes) were randomized to receive usual

care or one-on-one nurse- and dietician-led case management that emphasized

behavior modification and medical management. At 15 months, the mean

Framingham risk score (FRS) had declined significantly more in the casemanagement group (by 0.92 points to 7.80) than in the usual-care group (by

0.19 points to 8.93). FRS changes were consistent across sex and racial

subgroups. Most of the advantage of case management was attributable to

significant declines in systolic and diastolic blood pressures. Using prior data

on the association between risk-factor modification and outcomes, the

researchers estimated that the case-management program would prevent 1

adverse cardiovascular event in every 200 patients.

Reducing Blood Pressure Levels Effectively in Practice

•

•

•

In the other study, six family medicine clinics in Iowa (serving 402 patients

with poorly controlled hypertension) were randomized to (1) an intervention in

which pharmacists monitored patients and offered treating physicians

guideline-based medication-intensification recommendations for lowering

blood pressure or (2) no intervention. Because clinics — not patients — were

randomized, baseline characteristics differed significantly in some respects; for

example, patients at the control clinics had lower initial blood pressures and

were more likely than intervention patients to have no insurance and to have

diabetes. The researchers adjusted for such differences and found that,

compared with patients at the control clinics, those at the intervention clinics

had significantly lower systolic blood pressure at 6 months (about 12 mm Hg

lower, on average, despite the baseline disadvantage) and were significantly

more likely to achieve blood pressure control (odds ratios: 3.2 in the overall

cohort and 4.7 among diabetic patients).

Comment: Each of these studies identified an intervention that reduced blood

pressure effectively among patients with uncontrolled risk factors in clinical

practice. However, both programs require substantial staffing, which is costly.

Without meaningful financial incentives for achieving risk-factor modification

in community practice, implementing such interventions in the broader

population would likely be difficult, despite their effectiveness.

— Frederick A. Masoudi, MD, MSPH

Conducting brief interventions

• workbook or information sheet

• advantages of workbook—gives patient

something to take home, think about, and

refer to

• Clinician sits beside patient while

discussing contents of workbook, or

information sheet.

• It conveys sense of teamwork; because

patient does not have to look at clinician, he

or she may experience less fear of stigma

and find communication easier

Identify goals

• what does patient want to achieve over next 3 mo

to 1 yr?

• include goals about physical health, activities and

hobbies, and relationships

• So you would like to be able to walk one mile

with your gramd kids. Lets start with the chair

exercise program, stand and walk in place 15

seconds 100 times a day, and work up to that mile

• You would like to lose 20 pounds so lets start by

eating breakfast and reducing some carbohydrates

and reducing high calorie foods from your diet

Screening: summary of

patient’s health habits

• Ask questions about exercise, smoking,

nutrition, alcohol use, and (particularly in

older adults) medications

• How much do you exercise?

• What do you eat?

• Do you eat breakfast?

• Do you drink fruit juices, soda, alcohol?

• Ask the patient which health habits he or

she wants help with?

Discussion

• Address patient’s health concerns, but allow

redirection of conversation to weight loss

• Ask patient for his or her definition of a good

weight

• Educate the patient about accepted definitions by

doing BMI, body fat, waist circumference, and fat

calipers

• Inquire about what patient likes about eating (eg,

taste, greater comfort in social situations, reduced

stress and/or loneliness);

• Gently inform patient of negative consequences

obesity

• Discuss reasons for cutting down on consumption

Weight loss agreement

• The clinician makes suggestion of goal for

reducing weight

• You may need to negotiate with patient

about frequency, timing, and/or quantity of

weight loss and appointments

• The patient may not agree, but clinician

records recommendations and both parties

sign agreement

Understanding Hunger

To understand how emotional or mindless eating work, it's important to

know about the two types of hunger:

• real hunger

– grows gradually

– you'll eat anything

– can wait

– you stop when you're full

– you feel good after eating

– you gain energy

• emotional hunger

– hits suddenly

– you crave a specific food (usually high in fat)

– needs to be satisfied instantly

– you can't stop, period

– you feel guilty after eating

– you gain weight

Get the Patient into a different

Mindset

Traditional diets are a short-term fix to a longterm problem.

But the key to losing weight and keeping it off

has to be learned over time.

Over time, healthy eating will become habit.

Over time, you'll become more active, and

more content.

Over time, your life can get more satisfying—

and stay that way.

How to start

•

•

•

•

Plan

Today decide what you will eat tomorrow.

Write it down and keep it in your pocket.

Here are three winning tips to get you

started.

How to start

• Don't let yourself go hungry

• Eat breakfast in the morning. You need high fiber

and protein to fill you up and make you less

hungry.

• Reduce carbohydrates except for a small serving

of dark chocolate in the morning, to give you

some immediate energy. Dark Chocolate has allot

of antioxidants that are good for you

• Try eating 3 main meals and healthy snacks in

between. This keeps you feeling satisfied while

avoiding cravings from your external hunger.

• Take time to plan and schedule tomorrow's

healthy meals—and stick to your plan.

How to get started

• Take 15 minute breaks

• Satiety—that's the feeling of being full.

Unfortunately there's about a 15-minute lag

between when you're stomach gets this

message and when you're brain gets it.

Eating more slowly can give your stomach

the quarter of an hour it needs to relay your

fullness status to your brain. Taking 15 can

help you avoid overeating. Find a partner

and make lunch and snacks at work a social

occasion. A little chat can make that 15

minutes feel like nothing.

How to get started

• Arm yourself with healthy snacks

Healthy snacks are a great way to stay satisfied

between meals and help make sure that you're

eating at least every 4 hours. Low-fat foods, like

fresh fruit, fat-free pudding cups, and low-fat

crackers, will keep you from getting too hungry

and grabbing the first thing you see. If you're

running around or working, keep some unsalted

pretzels in your bag. Have some hummus in your

work fridge and bring in some carrot and celery

sticks. Give yourself options when you're working

or on the move.

We won't sugar coat it. It's hard to eat healthy when you eat out. Restauran

meals usually contain more salt and fat and sugar than the dishes you whip

up at home. But with a little insight, you can hit your favorite restaurants

and still eat for optimum health.

Look for the low-fat proteins. Favor low-fat food prep techniques like

grilling. Watch out for those hidden calories-they're lurking in mayo and in

cream-based sauces. And remember, restaurant portions are generally way

more food than you need.

Go for chicken and seafood-protein options with less saturated fat than red

meat

Ask for meat and fish to be grilled, definitely not fried

Make sure there are veggies on your plate

Go for tomato-based sauces as opposed to cream-based

Always order dressings on the side-so you stay in control, and see if there

are lower-fat alternatives available

Try mustard instead of mayo, or choose a low-fat mayo

Forget that guilt-trip your parents gave you about always cleaning your

plate. Leaving food on your plate is a victory, proof of your new-found

Restaurant dinning tactics

• Stick to the appetizer and salad sections of the menu. Make

veggie-based choices for your appetizers. Make the main

course a Cobb or grilled chicken salads. Avoid the fried

chicken-strip salad and the Caesar salad.

• Dip into salad dressing. Go for a fat-free or low-fat

dressing. Dip your fork into the dressing, and then the

salad-you'll still get the flavor you want, but not more than

you need.

• You're special-so don't be shy about special orders. Most

restaurants are happy to modify meals to make customers

happy. Don't be afraid to ask the server how a dish is

prepared. If the dish is high in fat, ask if they can cook the

steak without butter, or grill or broil the fish instead of

frying. Even if you have to pay a little extra, the benefits to

your health are worth the small difference in price.

Restaurant dinning tactics

• Always be the first to order. Listening to the choices that friends or

family make at restaurants may influence your decision, even if you

have the best intentions. Eliminate the temptation by being the first to

order. When you're done eating, ask for your plate to be removed, so

you don't pick.

• Order à la carte This is especially true for fast-food restaurants. For

instance, the regular price for a sandwich might be $3, but for $4 you

also get chips and a soda. You might think you saved money, but you

actually spent more, got food you didn't want, and extra calories you

don't need.

• Split meals with a friend. Many restaurant portions are enough for two

people to split-and making a meal a social occasion has the added

benefit of forcing you to eat more slowly, so you sense satiety before

you've overeaten. If you're on your own, get a doggie bag and place

half your meal in it when it is served. It will keep that portion out of

sight and make a great lunch the next day.

Restaurant dinning tactics

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Be vigilant-hidden calories can be anywhere. Many dishes contain more calories than you realize

because of breading, sauces, or frying. This is how hidden fat sneaks into your meal. If you aren't

certain what a meal comes with or how it is prepared, ask your server. If you see any of the following

words describing a menu item, your stealth calorie detector should start tingling.Au gratin

Parmesan

Cheese sauce

Scalloped

Rich

Creamy, cream sauce

Buttered, buttery

Pastry

Breaded

Fried

Seasoned

Southern-style

Limit your alcohol. Alcohol is loaded with empty calories and it's all too easy to consume too much

alcohol without thinking about it, especially when you're with friends, having a Friday lunch, or

blowing off steam after work. Stick to white wines and the lighter versions of your favorite lager

beer. Sparkling water with lime or lemon is a refreshing, healthful alternative.

Ban the breadbasket. Whether it's dinner rolls, breadsticks, or tortilla chips, ask the server not to

bring it, or push it out of immediate reach. The starch basket tends to contain a lot of refined whiteflour products-lots of calories, minimal nutritional value.

Restaurant dinning tactics

• Skip dessert or have fruit-based desserts. Resist dessert if you're full

and not internally hungry. Remind yourself you can have something

later, when your body-not your psyche-is hungry again. Otherwise,

consider good-tasting but low-calorie choices like sorbet, low-fat or

fat-free frozen yogurt, angel food cake, or fresh fruit.

• Ask for backup. Let your buddies in on your program. True friends

will embrace an opportunity to help you. Ask them to keep the starch

basket on their side of the table, and not egg you on to that rich dessert

or second glass of Pinot grigio.

• Monitor your emotions. Slipping up is human, but you are less likely

to do it if you ask yourself "What do I want from this meal?" before

you enter the restaurant. If you do overeat, don't kick yourself. You're

human and you've embraced a long term-based positive program for

change. And, if you do decide to eat more, don't consider it a

catastrophe later. Review your past Steps (accomplishments), chat with

peers, or write in your journal to get back on track. One meal will not

make or break your program for healthier change.

Ten Myths About Obesity

Tobacco-related mortality

• data from Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC) showed that obesityrelated mortality growing at rate that would

soon overtake tobacco- related mortality

• methodology of data analysis criticized

• findings refuted

• tobacco remains leading cause of

preventable death in United States (obesity

second)

Childhood obesity: only partially

true that epidemic slowing down

• overweight in children defined as body

mass index (BMI) >85th percentile of

average weight for age group,

• based on cohort from 1960s and 1970s

(obese >95th percentile,

• severely obese >97th percentile)

• downward trend

• in childhood obesity among whites, but

increase seen in black and Latino

communities

Effect of weight on mortality

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

BMI—underweight <18.5;

normal 18.5 to 25

overweight 25 to 30

obesity class I 30 to 35

obesity class II 35 to 40

obesity class III (extreme obesity) >40

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data—3 studies over 20

yr; slightly higher mortality of underweight category largely due to smoking (most

smokers thinner)

obesity (all classes) associated with excess mortality, but risk not dramatically higher

(relative risk [RR] 1.8)

overweight (BMI 25-30) not associated with excess mortality

in blacks BMIs of 27 to 30 associated with normal outcomes

while in Asians, BMIs as low as 23 may be associated with excess mortality

clinician’s role—determine whether patient has type of overweight associated with

adverse outcomes

look for metabolic syndrome (measure waist circumference, blood pressure, lipids)

take family history

current data—risk attributable to obesity decreasing over time, possibly because of

better management of related conditions

Overweight and Mortality in

an Older Population

•

•

•

•

•

•

Above-normal BMI was somewhat protective in women.

Are overweight elders at elevated risk for death, compared with those whose weight is

normal? To find out, Israeli researchers identified about 2400 Jerusalem elders (age

range, 70–85 at baseline) and followed them for 3 to 18 years. Normal, overweight, and

obese were defined as body-mass index (BMI) of 18 to 24.9 kg/m2, 25 to 29.9, and 30,

respectively.

In analyses that were adjusted for potentially confounding factors that could predispose

to death, women who were overweight or obese had significantly lower mortality than

women with normal BMIs. In men, mortality was similar in all three BMI categories. In

additional analyses, the researchers omitted deaths that occurred during the first several

years of follow-up, to account for "reverse causality" (which would occur if lowerweight people had diseases at baseline that would cause death within a relatively short

time); this maneuver did not affect the results.

Comment: In this study of an older population, being overweight or mildly obese was

not associated with shorter survival. Indeed, having above-normal BMI was somewhat

protective in women. These results should not be used to justify weight gain as people

age; rather, the implication is that overweight people in their 70s and 80s should not

necessarily be pushed to lose weight if they are otherwise active and well. These results

do not apply to severe obesity, which was not well-represented in this cohort.

— Allan S. Brett, MD

Published in Journal Watch General Medicine January 19, 2010

Case: woman 40 yr of age with

BMI 33; which abnormality best

• predicts

g

her 10-yr mortality? waist

circumference (36 in); fasting blood

glucose (110 mg/dL)

systolic blood pressure (BP; 140 mm

Hg)

triglycerides (185 mg/dL); exercise

test (stopped after stage 2)

answer

• —exercise test best

predictor

Fit and fat

• study confirmed earlier findings that sedentary

lifestyle doubles risk for premature death over 14

yr

• Fitness more important than weight for

measurement of health

• study showed fat but fit subjects lived longer than

thin but unfit subjects

• findings not replicated in other studies, but fitness

always shown to mitigate weight-related

morbidities

• urge patients to become as fit as possible,

regardless of their weight

Exercise

• not sufficient for weight loss

• improves variety of metabolic factors (small

dose-response effect) with or without weight loss

• recommend focusing initially on exercise duration

and frequency rather than on intensity

• That is why doing a body fat % is important. You

can tell patient even if you do not lose weight if on

your next visit your body fat is less you have more

muscle you are doing a good job and you are

healthier.

• By doing multiple measures you have multiple

ways to measure fitness.

Diet

• necessary for weight loss

• transtheoretical model’s stages of change applicable to

prescribing diet and weight loss strategies

• intervention should focus on stage of patient’s change

• diet type less important than adherence to Diet

• similar effectiveness seen with various popular diets,

including meal replacement (very low calorie), Atkins (low

carbohydrate), Ornish (vegetarian); Zone (balanced

macronutrient)

• mean intake 1400 calories/day on all diets

• Lowcarbohydrate approach possibly slightly better

• Universal use of low-fat diet no longer evidence-based

• patient should have adequate social support and frequent

visits with peer support, dietician, or physician

Rapid weight loss

• very low calorie diet (VLCD)—800 calories/day

• preplanned meals with adequate vitamins, minerals, and

proteins

• meta-analysis showed patients on VLCD lose weight twice

as quickly as those on traditional low-calorie diet (LCD;

1200 to 1400 calories/day) in short term;

• LCD in clinical setting results in loss of 5% to 10%

(average 7.5%) of patient’s original weight

• VLCD 15%

• weight loss in short term; VLCD indicated in patients who

want to lose high volume of weight without surgery

• VLCD indicated In patients with need for rapid weight loss

(eg, orthopedist recommends knee surgery, but requires

that patient first lose 50 lb or patient too heavy for bariatric

surgery table)

Average Weight Loss

•

•

•

•

Low Calorie Diet 5 to 10% of body weight

7.5 % is average

Very Low Calorie Diet 15% of body weight

Gastric bypass 30% of body weight

A very low-calorie diet

(VLCD)

•

•

•

A very low-calorie diet (VLCD) is a doctor-supervised diet that typically uses

commercially prepared formulas to promote rapid weight loss in patients who

are obese. These formulas, usually liquid shakes or bars, replace all food

intake for several weeks or months. VLCD formulas need to contain

appropriate levels of vitamins and micronutrients to ensure that patients meet

their nutritional requirements. Some physicians also prescribe VLCDs made

up almost entirely of lean protein foods, such as fish and chicken. People on a

VLCD consume about 800 calories per day or less.

VLCD formulas are not the same as the meal replacements you can find at

grocery stores or pharmacies, which are meant to substitute for one or two

meals a day. Over-the-counter meal replacements such as bars, entrees, or

shakes, should account for only part of one’s daily calories.

When used under proper medical supervision, VLCDs may produce significant

short-term weight loss in patients who are moderately to extremely obese.

VLCDs should be part of comprehensive weight-loss treatment programs that

include behavioral therapy, nutrition counseling, physical activity, and/or drug

treatment.

VLCDs

•

•

•

VLCDs are designed to produce rapid weight loss at the start of a weight-loss

program in patients with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 and

significant comorbidities. BMI correlates significantly with total body fat

content. It is calculated by dividing a person’s weight in pounds by height in

inches squared and multiplied by 703.

Use of VLCDs in patients with a BMI of 27 to 30 should be reserved for those

who have medical conditions due to overweight, such as high blood pressure.

In fact, all candidates for VLCDs undergo a thorough examination by their

health care provider to make sure the diet will not worsen preexisting medical

conditions. Lastly, these diets are not appropriate for children or adolescents,

except in specialized treatment programs.

Very little information exists regarding the use of VLCDs in older adults.

Because adults over age 50 already experience depletion of lean body mass,

use of a VLCD may not be warranted. Also, people over 50 may not tolerate

the side effects associated with VLCDs because of preexisting medical

conditions or the need for other medicines. Doctors must evaluate on a caseby-case basis the potential risks and benefits of rapid weight loss in older

adults, as well as in patients who have significant medical problems or are on

medications. Furthermore, doctors must monitor all VLCD patients

regularly—ideally every 2 weeks in the initial period of rapid weight loss—to

be sure patients are not experiencing serious side effects.

VLCD

• A VLCD may allow a patient who is moderately to

extremely obese to lose about 3 to 5 pounds per week, for

an average total weight loss of 44 pounds over 12 weeks.

Such a weight loss can rapidly improve obesity-related

medical conditions, including diabetes, high blood

pressure, and high cholesterol.

• The rapid weight loss experienced by most people on a

VLCD can be very motivating. Patients who participate in

a VLCD program that includes lifestyle treatment typically

lose about 15 to 25 percent of their initial weight during

the first 3 to 6 months. They may maintain a 5-percent

weight loss after 4 years if they adopt a healthy eating plan

and physical activity habits.

side effects

• Many patients on a VLCD for 4 to 16 weeks report minor

side effects such as fatigue, constipation, nausea, or

diarrhea. These conditions usually improve within a few

weeks and rarely prevent patients from completing the

program. The most common serious side effect is gallstone

formation. Gallstones, which often develop in people who

are obese, especially women, are even more common

during rapid weight loss. Research indicates that rapid

weight loss may increase cholesterol levels in the

gallbladder and decrease its ability to contract and expel

bile. Some medicines can prevent gallstone formation

during rapid weight loss. Your health care provider can

determine if these medicines are appropriate for you

Maintaining Weight Loss

• Studies show that the long-term results of VLCDs vary widely, but

weight regain is common. Combining a VLCD with behavior therapy,

physical activity, and active follow-up treatment may help increase

weight loss and prevent weight regain.

• In addition, VLCDs may be no more effective than less severe dietary

restrictions in the long run. Studies have shown that following a diet of

approximately 800 to 1,000 calories produces weight loss similar to

that seen with VLCDs. This is probably due to participants’ better

compliance with a less restrictive diet.

• For most people who are obese, their condition is long-term and

requires a lifetime of attention even after formal weight-loss treatment

ends. Therefore, health care providers should encourage patients who

are obese to commit to permanent changes of healthier eating, regular

physical activity, and an improved outlook about food

Study showing Medifast's effectiveness in patients with type 2 diabetes

published in 'The Diabetes Educator'

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

OWINGS MILLS, Md., February 11, 2008- /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ -- Medifast, Inc. (NYSE: MED) today announced that a study

conducted by researchers at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, showing the Medifast Program

outperforms the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommended diet for patients with type 2 diabetes, has been published in the

January/February issue of 'The Diabetes Educator'. The peer-reviewed journal is the official journal of the American Association of

Diabetes Educators.

The examiner of the study from Johns Hopkins University submitted the study and informed Medifast that the study has been published

in the most appropriate venue to help train diabetes educators about the effectiveness of Medifast Meal Replacements in the treatment

of type 2 diabetes. The study was finalized for publication within the last 12 months after being presented to physicians and scholars

attending the American Diabetes Association Convention in 2005.

"This study is one of many that validate the efficacy of Medifast Meal Replacements in the clinical setting," said Brad MacDonald,

Chairman of the Board, Medifast, Inc. "Medifast continues to invest in the research and development of its products and programs to

ensure that our claims to consumers are the most documented and credible in the industry."

In the study, the Medifast Program outperformed the ADA recommended diet in weight loss, adherence and biochemical outcomes.

These findings suggest a re-evaluation of the ADA recommendation, which currently does not promote portion-controlled meal

replacement programs in weight loss and weight maintenance for individuals with diabetes, is warranted.

The results of the study also suggest that meal replacements may achieve the same outcomes in diabetics as bariatric surgery (though

over the longer term), while mitigating the increased risk of morbidity and mortality associated with these more dangerous treatment

approaches.

"A close friend of mine had some serious complications because of type 2 diabetes and it scared me to death," said Medifast client

Steven Eldridge, of Raytown, MO. "I was suffering from the disease myself and decided to consult my doctor. He said the best thing I

could do is to lose the weight, and that's when I found Medifast. I lost 114 pounds in 5 months on the Medifast Program and am totally

off my diabetes medication for the first time in 6 years, which is an absolute miracle, and I have Medifast to thank!"

The study compared Medifast's effectiveness for weight control in people with type 2 diabetes to the standard ADA recommended

dietary guidelines. The study enlisted 112 overweight or obese people with type 2 diabetes using two weight loss approaches of equal

caloric prescription - the Medifast Program and a traditional reduced-calorie diet based on the ADA recommended dietary guidelines.

According to the results, participants randomized to receive Medifast lost twice as much weight and were twice as compliant with the

diet as participants following the standard ADA diet. Approximately 40 percent of the Medifast participants lost greater than 5 percent

of their initial weight, compared with 12 percent of those on the standard ADA diet. Additionally, 24 percent of the Medifast users

decreased or eliminated their diabetes medication, compared to 0 percent on the standard ADA diet.

Medifast will continually participate in studies in the future, which will add even more credibility to the Medifast Brand and Programs.

For more than 25 years Medifast has been prescribed by practitioners as a safe and effective program that yields significant results and

has been proven to provide significant weight loss of 2-5 pounds per week.

"Over 20,000 physicians have recommended Medifast since 1980 and millions of consumers have realized the health and wellness

benefit of our program," says Michael S. McDevitt, Chief Executive Officer, Medifast, Inc. "The publication of this study adds to

Medifast's already stellar reputation in the medical community."

The Medifast Plan

For Women

• The Medifast 5 & 1 Plan helps women lose weight quickly, leading to

tremendous improvements in overall health. Medifast is much more

than the traditional, fad diets that may have failed your patients in the

past. Medifast helps your patients lose the weight - and teaches them

how to keep it off! The Medifast program is convenient, portioncontrolled, and simple to follow. Your patients will see and feel results

in the first week!

• Most women start by ordering the Medifast for Women 4-Week

Package. With this package your patients receive the most popular

Medifast Meals - and save over $30!

• Medifast also has a unique line of shakes, specially formulated to meet

the specific health needs of women. Medifast Plus for Women's Health

Shakes contain black cohosh, Echinacea, and chaste tree berry - these

ingredients help reduce symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes or

night sweats.

The Medifast Plan

For Men

• The Medifast 5 & 1 Plan helps your patients lose weight

quickly, improve their overall health, and take charge of

their eating for life. Remember, Medifast is a lifestyle

change, not just a short-term weight loss solution. We

won't abandon your patients the way fad diets have in the

past. Our Transition, Maintenance and Exercise Plans pick

up where the 5 & 1 Plan ends - and teach your patients

how to sustain their weight loss results long term!

• The quick weight loss results your patients experience will

inspire and motivate them to embrace Medifast as an

essential part of their new, healthy lifestyle.

• Most men start by ordering the Medifast for Men 4-Week

Package and save over $30 on the most popular Medifast

Meals.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

The Medifast Plan

For Seniors

Medifast for Seniors is a Medifast Program specifically designed for adults over age 70. The

Medifast for Seniors Program is different from the Medifast 5 & 1 Plan.

Maintaining a healthy weight is beneficial for people of all ages. As one gets older, achieving and

maintaining a healthy weight becomes crucial to their overall state of health. The Medifast for

Seniors Program is convenient and easy to follow, emphasizing portion-controlled eating at regular

intervals throughout the day.

Seniors have 2 options for Medifast Meal Plans. As their physician, you can help decide which

option is right for your patient.

OPTION 1: The Medifast 4 & 2 & 1 Plan

4 Medifast Meals + 2 Lean & Green Meals + 1 Healthy Snack

1000-2000 calories daily

100+ grams of carbohydrates daily

Weight loss will be slow and steady

Patient will not be in fat burning state with this plan

OPTION 2: The Medifast 5 & 2 & 2 Plan

5 Medifast Meals + 2 Lean & Green Meals + 2 Healthy Snacks

1,300-1,500 calories daily

130+ grams carbohydrates daily

Weight loss may be slower paced, but patient will still lose weight at a healthy rate

Patient will not be in fat-burning state with this plan

OPTIFAST Program

•

•

•

•

At the heart of the OPTIFAST Program is a portion-controlled, calorically

precise, nutritionally complete diet that takes the guesswork out of eating. The

benefits of OPTIFAST shakes, soups and bars include:

High-quality, complete nutritionPre-portioned and calorie-controlled

servingsStimuli narrowingQuick and simple preparationFreedom from

having to make food choices

During the Active Weight Loss phase, patients consume only the OPTIFAST

meal replacements. Hunger typically goes away after the first week. Many

patients report increased energy, attributed to more stable blood sugar levels,

balanced diet, decreased weight, and increased activity level.

The active weight loss phase is followed by a 4-6 week transition period

during which participants gradually add self-prepared foods back to their diets.

Participants move to a long-term weight management program rich in fruits

and vegetables, grains and low-fat proteins. During the program they will have

learned techniques to include small amounts of their favorite foods into their

new healthy lifestyle. The Food & Nutrition section ofResources contains links

to many helpful nutrition and meal planning resources.

OPTIFAST provider

•

•

•

•

Becoming an OPTIFAST provider means access to a vast array of expertise

and services to member clinics, including:

Skilled Resources

– The OPTIFAST Team includes former and current OPTIFAST Program

Directors, physicians, registered dietitians, registered nurses, nutrition

scientists, exercise physiologists and clinical researchers.

Professional Resources

– Key program staff learn how to manage a comprehensive weight

management program from business, medical, nutritional and educational

perspectives. Components include:

– • The OPTIFAST Program Training Startup Manual

– • Online Training Modules

– • 2-day live training in Minneapolis, MN

– • Ongoing mentoring by your OPTIFAST account manager

– • Regional OPTIFAST Conferences

Clinical Support Services

– In addition to customized assistance from their account manager,

OPTIFAST clinics receive access to a wealth of research data, marketing

materials and support, and operations support.

Optifast and Bariatric Surgery

• Nutritional therapy prior to bariatric procedures can

provide significant benefits to surgeons and patients alike:

• Presurgery

• Improved transition to postoperative diet and

behaviorReduced fatty liver and decrease in liver

volumeDecreased visceral adipose tissue

• Postsurgery

• Reduced risk of liver trauma and blood lossReduced

laparoscopic procedure timeIncreased weight loss first

year postoperatively

• Some OPTIFAST clinics and bariatric surgery centers

offer presurgical support programs to help prepare patients

for surgery. Many OPTIFAST clinics also welcome

bariatric patients into their overall long-term management

programs and continue to provide OPTIFAST product to

those patients who were started on OPTIFAST prior to

After weight loss

• myth that after successful weight loss, patients can

return to “sensible” (1800 calories/day) diet

• Patient must maintain 1400 calorie/day diet for rest of life

or weight will be regained

• supported by data from National Weight Control Registry

• maintaining weight loss requires high levels of physical

activity ( 1 hr of moderate-intensity exercise daily)

• Exercise 6 days a week

• low-fat or low-carbohydrate diet

• regular selfmonitoring of weight

• “grazing” rather than binging

• Avoid fast foods

• weekend diet and exercise regimen same as weekday

regimen

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

NWCR Facts

You may find it interesting to know about the people who have enrolled in the registry thus far.

80% of persons in the registry are women and 20% are men.

The "average" woman is 45 years of age and currently weighs 145 lbs, while the "average" man is 49

years of age and currently weighs 190 lbs.

Registry members have lost an average of 66 lbs and kept it off for 5.5 years.

These averages, however, hide a lot of diversity:

– Weight losses have ranged from 30 to 300 lbs.

– Duration of successful weight loss has ranged from 1 year to 66 years!

– Some have lost the weight rapidly, while others have lost weight very slowly--over as many as

14 years.

We have also started to learn about how the weight loss was accomplished: 45% of registry

participants lost the weight on their own and the other 55% lost weight with the help of some type of

program.

98% of Registry participants report that they modified their food intake in some way to lose weight.

94% increased their physical activity, with the most frequently reported form of activity being

walking.

There is variety in how NWCR members keep the weight off. Most report continuing to maintain a

low calorie, low fat diet and doing high levels of activity.

•

–

–

–

–

78% eat breakfast every day.

75% weigh themselves at least once a week.

62% watch less than 10 hours of TV per week.

90% exercise, on average, about 1 hour per day.

Persons successful at long-term weight

loss and maintenance continue to

consume a low-energy, low-fat diet.

•

•

•

•

•

Shick SM, Wing RR, Klem ML, McGuire MT, Hill JO, Seagle H.

Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, PA 15213, USA.

Comment in:

J Am Diet Assoc. 1998 Nov;98(11):1273.

OBJECTIVES: To describe the dietary intakes of persons who successfully maintained weight loss and to determine

if differences exist between those who lost weight on their own vs those who received assistance with weight loss (eg,

participated in a commercial or self-help program or were seen individually by a dietitian). Intakes of selected

nutrients were also compared with data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES

III) and the 1989 Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs). SUBJECTS: Subjects were 355 women and 83 men,

aged 18 years or older, primarily white, who had maintained a weight loss of at least 13.6 kg for at least 1 year, and

were the initial enrollees in the ongoing National Weight Control Registry. On average, the participants had lost 30 kg

and maintained the weight loss for 5.1 years. METHODS: A cross-sectional study in which subjects in the registry

completed demographic and weight history questionnaires as well as the Health Habits and History Questionnaire

developed by Block et al. Subjects' dietary intake data were compared with that of similarly aged men and women in

the NHANES III cohort and to the RDAs. Adequacy of the diet was assessed by comparing the intake of selected

nutrients (iron; calcium; and vitamins C, A, and E) in subjects who lost weight on their own or with assistance.

RESULTS: Successful maintainers of weight loss reported continued consumption of a low-energy and low-fat diet.

Women in the registry reported eating an average of 1,306 kcal/day (24.3% of energy from fat); men reported

consuming 1,685 kcal (23.5% of energy from fat). Subjects in the registry reported consuming less energy and a lower

percentage of energy from fat than NHANES III subjects did. Subjects who lost weight on their own did not differ

from those who lost weight with assistance in regards to energy intake, percent of energy from fat, or intake of

selected nutrients (iron; calcium; and vitamins C, A, and E). In addition, subjects who lost weight on their own and

those who lost weight with assistance met the RDAs for calcium and vitamins C, A, and E for persons aged 25 years

or older. APPLICATIONS: Because continued consumption of a low-fat, low-energy diet may be necessary for longterm weight control, persons who have successfully lost weight should be encouraged to maintain such a diet.

Behavioral strategies of individuals who

have maintained long-term weight losses.

•

•

•

McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, Hill JO.

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, PA 15213, USA. zie4@cdc.gov

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of the present study was to compare the behaviors of

individuals who have achieved long-term weight loss maintenance with those of

regainers and weight-stable controls. RESEARCH METHODS AND PROCEDURES:

Subjects for the present study were participants in a random-digit dial telephone survey

that used a representative sample of the U.S. adult population. Eating, exercise, selfweighing, and dietary restraint characteristics were compared among weight-loss

maintainers: individuals who had intentionally lost > or =10% of their weight and

maintained it for > or = 1 year (n = 69), weight-loss regainers: individuals who

intentionally lost > or = 10% of their weight but had not maintained it (n = 56), and

weight-stable controls: individuals who had never lost > or = 10% of their maximum

weight and had maintained their current weight (+/-10 pounds) within the past 5 years (n

= 113). RESULTS: Weight-loss maintainers had lost an average of 37 pounds and

maintained it for over 7 years. These individuals reported that they currently used more

behavioral strategies to control dietary fat intake, have higher levels of physical activity

(especially strenuous activity), and greater frequency of self-weighing than either the

weight-loss regainers or weight-stable controls. Maintainers and regainers did not differ

in reported levels of dietary restraint, but both had higher levels of restraint than the

weight-stable controls. DISCUSSION: These results suggest that weight-loss

maintainers use more behavioral strategies to control their weight than either regainers

or weight-stable controls. It would thus appear that long-term weight maintenance

requires ongoing adherence to a low-fat diet and an exercise regimen in addition to

continued attention to body weight.

What predicts weight regain in a

group of successful weight losers? .

•

•

•

•

•

McGuire MT, Wing RR, Klem ML, Lang W, Hill JO.

Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh Medical School, USA.

zie4@cdc.gov

Erratum in:

J Consult Clin Psychol 1999 Jun;67(3):282.

This study identified predictors of weight gain versus continued maintenance among

individuals already successful at long-term weight loss. Weight, behavior, and

psychological information was collected on entry into the study and 1 year later. Thirtyfive percent gained weight over the year of follow-up, and 59% maintained their weight

losses. Risk factors for weight regain included more recent weight losses (less than 2

years vs. 2 years or more), larger weight losses (greater than 30% of maximum weight

vs. less than 30%), and higher levels of depression, dietary disinhibition, and binge

eating levels at entry into the registry. Over the year of follow-up, gainers reported

greater decreases in energy expenditure and greater increases in percentage of calories

from fat. Gainers also reported greater decreases in restraint and increases in hunger,

dietary disinhibition, and binge eating. This study suggests that several years of

successful weight maintenance increase the probability of future weight maintenance

and that weight regain is due at least in part to failure to maintain behavior changes.

The prevalence of weight loss

maintenance among American adults.

•

•

•

McGuire MT, Wing RR, Hill JO.

University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, PA, USA. mcguire@epi.umn.edu

BACKGROUND: Previous studies suggest that few individuals achieve long-term weight loss

maintenance. Because most of these studies were based on clinical samples and focused on only one

episode of weight loss, these results may not reflect the actual prevalence of weight loss maintenance

in the general population. DESIGN: A random digit dial telephone survey was conducted to

determine the point prevalence of weight loss maintenance in a nationally representative sample of

adults in the United States. Weight loss maintainers were defined as individuals who, at the time of

the survey, had maintained a weight loss of > or =10% from their maximum weight for at least 1 y.

The prevalence of weight loss maintenance was first determined for the total group (n = 500), and

then for the subgroup of individuals who were overweight (body mass index BMI > or =27 kg/m2 at

their maximum (n = 228). RESULTS: Weight loss was quite common in this sample: 54% of the

total sample and 62% of those who were ever overweight reported that they had lost > or =10% of

their maximum weight at least once in their lifetime, with approximately one-half to two-thirds of

these cases being intentional weight loss. Among those who had achieved an intentional weight loss

of > or =10%, 47-49% had maintained this weight loss for at least 1 y at the time of the survey; 2527% had maintained it for 5 y or more. Fourteen percent of all subjects surveyed and 21% of those

with a history of obesity were currently 10% below their highest weight, had reduced intentionally,

and had maintained this 10% weight loss for at least 1 y. CONCLUSIONS: A large proportion of the

American population has lost > or =10% of their maximum weight and has maintained this weight

loss for at least 1 y. These findings are in sharp contrast to the belief that few people succeed in longterm weight loss maintenance.

Three-year weight change in successful

weight losers who lost weight on a lowcarbohydrate diet.

•

•

•

•

Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007 Oct;15(10):2470-7.

Phelan S, Wyatt H, Nassery S, Dibello J, Fava JL, Hill JO, Wing RR.

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, Brown Medical School, 196 Richmond Street,

Providence, RI 02903, USA. sphelan@lifespan.org

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to evaluate long-term weight loss and eating and

exercise behaviors of successful weight losers who lost weight using a low-carbohydrate diet.

RESEARCH METHODS AND PROCEDURES: This study examined 3-year changes in weight,

diet, and physical activity in 891 subjects (96 low-carbohydrate dieters and 795 others) who enrolled

in the National Weight Control Registry between 1998 and 2001 and reported >or=30-lb weight loss

and >or=1 year weight loss maintenance. RESULTS: Only 10.8% of participants reported losing

weight after a low-carbohydrate diet. At entry into the study, low-carbohydrate diet users reported

consuming more kcal/d (mean +/- SD, 1,895 +/- 452 vs. 1,398 +/- 574); fewer calories in weekly

physical activity (1,595 +/- 2,499 vs. 2,542 +/- 2,301); more calories from fat (64.0 +/- 7.9% vs. 30.9

+/- 13.1%), saturated fat (23.8 +/- 4.1 vs. 10.5 +/- 5.2), monounsaturated fat (24.4 +/- 3.7 vs. 11.0 +/5.1), and polyunsaturated fat (8.6 +/- 2.7 vs. 5.5 +/- 2.9); and less dietary restraint (10.8 +/- 2.9 vs.

14.9 +/- 3.9) compared with other Registry members. These differences persisted over time. No

differences in 3-year weight regain were observed between low-carbohydrate dieters and other

Registry members in intent-to-treat analyses (7.0 +/- 7.1 vs. 5.7 +/- 8.7 kg). DISCUSSION: It is

possible to achieve and maintain long-term weight loss using a low-carbohydrate diet. The long-term

health effects of weight loss associated with a high-fat diet and low activity level merits further

investigation.

Holiday weight management by successful

weight losers and normal weight

individuals.

•

•

•

•

J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008 Jun;76(3):442-8.

Phelan S, Wing RR, Raynor HA, Dibello J, Nedeau K, Peng W.

Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown Medical School, Providence, RI

02903, USA. sphelan@lifespan.org

This study compared weight control strategies during the winter holidays among

successful weight losers (SWL) in the National Weight Control Registry and normal

weight individuals (NW) with no history of obesity. SWL (n = 178) had lost a mean of

34.9 kg and had kept > or = 13.6 kg off for a mean of 5.9 years. NW (n = 101) had a

body mass index of 18.5-24.9 kg/m(2). More SWL than NW reported plans to be

extremely strict in maintaining their usual dietary routine (27.3% vs. 0%) and exercise

routine (59.1% vs. 14.3%) over the holidays. Main effects for group indicated that SWL

maintained greater exercise, greater attention to weight and eating, greater stimulus

control, and greater dietary restraint, both before and during the holidays. A Group x

Time interaction indicated that, over the holidays, attention to weight and eating

declined significantly more in SW than in NW. More SWL (38.9%) than NW (16.7%)

gained > or = 1 kg over the holidays, and this effect persisted 1 month later (28.3% and

10.7%, respectively). SWL worked harder than NW did to manage their weight, but they

appeared more vulnerable to weight gain during the holidays. (c) 2008 APA, all rights

reserved

Weight-loss maintenance in successful weight

losers: surgical vs non-surgical methods.

•

•

•

•

Int J Obes (Lond). 2009 Jan;33(1):173-80. Epub 2008 Dec 2.

Bond DS, Phelan S, Leahey TM, Hill JO, Wing RR.

Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown

University/The Miriam Hospital, Providence, RI, USA. dbond@lifespan.org

OBJECTIVE: As large weight losses are rarely achieved through any method except bariatric

surgery, there have been no studies comparing individuals who initially lost large amounts of weight

through bariatric surgery or non-surgical means. The National Weight Control Registry (NWCR)

provides a resource for making such unique comparisons. This study compared the amount of weight

regain, behaviors and psychological characteristics in NWCR participants who were equally

successful in losing and maintaining large amounts of weight through either bariatric surgery or nonsurgical methods. DESIGN: Surgical participants (n=105) were matched with two non-surgical

participants (n=210) on gender, entry weight, maximum weight loss and weight-maintenance

duration, and compared prospectively over 1 year. RESULTS: Participants in the surgical and nonsurgical groups reported having lost approximately 56 kg and keeping > or =13.6 kg off for 5.5+/-7.1

years. Both groups gained small but significant amounts of weight from registry entry to 1 year

(P=0.034), but did not significantly differ in magnitude of weight regain (1.8+/-7.5 and 1.7+/-7.0 kg

for surgical and non-surgical groups, respectively; P=0.369). Surgical participants reported less

physical activity, more fast food and fat consumption, less dietary restraint, and higher depression

and stress at entry and 1 year. Higher levels of disinhibition at entry and increased disinhibition over

1 year were related to weight regain in both groups. CONCLUSIONS: Despite marked behavioral

differences between the groups, significant differences in weight regain were not observed. The

findings suggest that weight-loss maintenance comparable with that after bariatric surgery can be

accomplished through non-surgical methods with more intensive behavioral efforts. Increased

susceptibility to cues that trigger overeating may increase risk of weight regain regardless of initial

weight-loss method.

Consistent self-monitoring of weight: a key

component of successful weight loss

maintenance.

•

•

•

•

Obesity (Silver Spring). 2007 Dec;15(12):3091-6.

Butryn ML, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR.

Department of Psychology, Drexel University, 245 N. 15th Street, MS 626, Philadelphia, PA 19102,

USA. mlb34@drexel.edu

OBJECTIVE: The objectives were to investigate the characteristics associated with frequent selfweighing and the relationship between self-weighing and weight loss maintenance. RESEARCH

METHODS AND PROCEDURES: Participants (n = 3003) were members of the National Weight

Control Registry (NWCR) who had lost >or=30 lbs, kept it off for >or=1 year, and had been

administered the self-weighing frequency assessment used for this study at baseline (i.e., entry to the

NWCR). Of these, 82% also completed the one-year follow-up assessment. RESULTS: At baseline,

36.2% of participants reported weighing themselves at least once per day, and more frequent

weighing was associated with lower BMI and higher scores on disinhibition and cognitive restraint,

although both scores remained within normal ranges. Weight gain at 1-year follow-up was

significantly greater for participants whose self-weighing frequency decreased between baseline and

one year (4.0 +/- 6.3 kg) compared with those whose frequency increased (1.1 +/- 6.5 kg) or

remained the same (1.8 +/- 5.3 kg). Participants who decreased their frequency of self-weighing were

more likely to report increases in their percentage of caloric intake from fat and in disinhibition, and

decreases in cognitive restraint. However, change in self-weighing frequency was independently

associated with weight change. DISCUSSION: Consistent self-weighing may help individuals

maintain their successful weight loss by allowing them to catch weight gains before they escalate and

make behavior changes to prevent additional weight gain. While change in self-weighing frequency

is a marker for changes in other parameters of weight control, decreasing self-weighing frequency is

also independently associated with greater weight gain.

Medications

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

medicines really are not effective

phentermine—approved for 6 wk of use

weight usually returns upon termination of use

sibutramine – approved for 1 yr use ineffective

orlistat—prescription-strength approved for 2-yr use

topiramate—not approved for weight loss

exenatide—not approved for weight loss

drug vs placebo studies

average loss 5% of original weight; study results unreliable because

subjects placed on diet and exercise programs and behavioral therapy

before start of medication trial

• no data suggest >1-yr use of weight-loss medications reduces obesityrelated morbidity and mortality

• drugs ineffective because multiple biologic systems (eg, central

nervous system, endocrine system) affect appetite, and when one

suppressed, others remain active or compensate

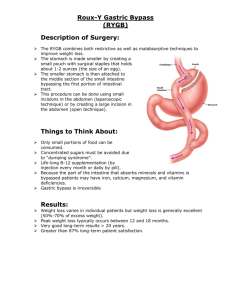

Surgery

• gastric bypass twice as effective as best

dietary intervention

• risk for death within 30-day post-operative

period 0.5% to 2.0%

• factors affecting outcome include surgeon’s

skill and patients’ preexisting comorbidities

Background for obesity surgery

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

obesity surgery differs from that of 7 to 10 yr ago

>50% of Americans overweight or obese

1 in 25 Americans qualify for weight-loss surgery

75% of obese children become morbidly obese adults

1 in 3 children born after 2000 will develop type 2 diabetes

each year 112,000 people die prematurely of obesity-related

conditions

(more than deaths from breast cancer, prostate cancer, and colorectal

cancer combined)

society incorrectly views obesity as result of acquired self-destructive

behavior, rather than as disease

obese individuals have lower rates of drug, tobacco, and alcohol use

than national averages

problem—food highly efficient vehicle for disease

Most smokers do not get lung cancer and few chronic alcohol abusers

get cirrhosis, but everyone who consumes more calories than they burn

will gain excess weight

Background for obesity surgery

• Candidates for weight-loss surgery

• National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria

recommend weight-loss surgery for patients

with BMI over 40, or BMI over 35 plus

hypertension, heart disease, sleep apnea, or

diabetes

• nonsurgical weight-loss treatments have

about a 95% long-term failure rate

• bariatric surgery only scientifically proven

method for long-term weight loss; improves

or cures diabetes, hypertension, sleep apnea,

and other weight-related morbidities

Laparoscopic surgery

• now standard bariatric procedure

• compared to open procedures, results in reduced incidence

of wound infections, hernias, deep venous thrombosis,

pulmonary embolism, and postoperative pneumnia as well

as less pain and faster recovery

• only 1% to 2% of patients undergoing laparoscopy develop

wound infection, hernia, or both (compared to 1 in 6

patients undergoing open procedures)

• recent improvements—standardized procedures

• collaboration among surgeons nationally

• improved patient selection

• procedure should be done in patients <400 lb, preferably

<300 lb as it is safer and more effective

Goals of surgery

• gastric banding—restriction of caloric

intake by restricting volume required for

feeling of satiation

• patients eat 3 4-oz meals daily

• patients taught how to construct a lowcalorie meal

• gastric bypass—restriction plus

malabsorption

People loss weight

in Gastric Bypass

surgery by three

basic mechanisms,

What are they?

Answer

• 1. Hormonal

• 2. Malabsorption

• 3. Dumping syndrome.

• What exactly is the

mechanism for each method?

Answer

• 1. Hormonal is the result of reduced Ghrelin

in the stomach. It is a hormone made by the

stomach that makes you feel hungry

• 2. Malabsorption because of bypassing part

of the small intestine

• 3. Dumping syndrome is an autonomic

response to eating high osmolarity foods

that as they pass from the reduced stomach

directly into the jejunem cause sweating,

distension and tachycardia. You get a bad

feeling and the result is an Antibuse effect

used to limit drinking Alcohol

NEJM Volume 346:1623-1630May 23, 2002Number 21Next

Plasma Ghrelin Levels after Diet-Induced Weight Loss or Gastric Bypass Surgery

David E. Cummings, M.D., David S. Weigle, M.D., R. Scott Frayo, B.S., Patricia A. Breen,

B.S.N., Marina K. Ma, E. Patchen Dellinger, M.D., and Jonathan Q. Purnell, M.D.

•

•

•

Our finding of markedly reduced ghrelin levels after gastric bypass suggests that suppression of

ghrelin can now be studied as a potential mechanism by which this procedure causes weight loss.

This hypothesis offers a plausible explanation for theparadoxical reduction of hunger between meals

that occurs after gastric bypass, as well as for the observation that the procedure is more effective

than gastroplasty in facilitating long-term weight loss.12,13,14,35,36,37,38,39,40 These operations

produce equivalent gastric restriction,35,41 but only gastric bypass isolates ghrelin cells from contact

with enteral nutrients.

The mechanism by which gastric bypass leads to a reduction in ghrelin levels remains to be

determined. Our data show thatingested nutrients powerfully regulate the level of circulating ghrelin.

Although an empty stomach is associated with an increasedghrelin level in the short term, it is

possible that the permanent absence of food in the stomach and duodenum that results fromgastric

bypass causes a continuous stimulatory signal that ultimately suppresses ghrelin production through

the process of "override inhibition." By this mechanism, continuous gonadotropin-releasing hormone

signaling initially stimulates but eventually suppresses gonadotropin secretion,42 and a similar

desensitization occurs with the unabated stimulation of growth hormone by growth-hormone–

releasing hormone.43 The possibility that override inhibition occurs in the case of ghrelin is suggested

by our data showing a progressive decline in the circulating level during an overnight fast (Figure

1 and Figure 2).24

In summary, 24-hour plasma ghrelin levels increase in response to diet-induced weight loss,

suggesting that ghrelin may play a part in the adaptive response that limits the amount of weight that

may be lost by dieting. We also found that ghrelin levels are abnormally low after gastric bypass,

raising the possibility that this operation reduces weight in part by suppressing ghrelinproduction.

These data suggest that ghrelin antagonists may someday be considered in the treatment of obesity.

Malabsorption

• Gastric bypass surgery bypasses the section of small bowel in which

most vitamins are digested and absorbed. Also, as seen below in the

excerpts taken from various medical sources, that stapling the stomach

can have some repercussions as far as vitamin digestion.

• Vitamin A

• Calcium

• Vitamin B12

– B12 fact sheet from NIH NOTE: sub lingual or B12 shots are

recommended

• Vitamin E

• Vitamin D

– Vitamin D fact sheet NIH

• Polyneuropathy (post stomach stapling)

• Selenium Deficiency

• Thiamin (vitamin B1 deficiency)

• Starvation

• Iron

Gastric dumping syndrome

•

•

•

•

Gastric dumping syndrome, or rapid gastric emptyingis a condition where

ingested foods bypass the stomach too rapidly and enter the small intestine

largely undigested. It happens when the upper end of the small intestine,

thejejunum, expands too quickly due to the presence of

hyperosmolar[jargon] food from the stomach. "Early" dumping begins

concurrently or immediately succeeding a meal. Symptoms of early dumping

include nausea,vomiting, bloating, cramping, diarrhea, dizziness and fatigue.

"Late" dumping happens 1 to 3 hours after eating. Symptoms of late dumping

include weakness, sweating, and dizziness. Many people have both types. The

syndrome is most often associated with gastric surgery.

It is speculated that "early" dumping is associated with difficulty digesting fats

while "late" dumping is associated with carbohydrates.[citation needed]

Rapid loading of the small intestine with hypertonic stomach contents can lead

to rapid entry of water into the intestinal lumen. Osmotic diarrhea, distension

of the small bowel (leading to crampy abdominal pain), and hypovolemia can

result.

In addition, people with this syndrome often suffer from low blood sugar,

or hypoglycemia, because the rapid "dumping" of food triggers the pancreas to

release excessive amounts of insulin into the bloodstream. This type of

hypoglycemia is referred to as "alimentary hypoglycemia".

Gastric bypass

• stomach stapled and cut to make new smaller stomach

• intestine attached to new stomach

• Stomach still makes digestive secretions that mix with bile and

pancreatic secretions

• current procedures bypass only onethird of gastrointestinal (GI) tract

• possible to achieve weight loss without predisposing patient to

nutritional deficiencies

• stomach stapled and cut to make new smaller stomach

• intestine attached to new stomach

• Stomach still makes digestive secretions that mix with bile and

pancreatic secretions

• current procedures bypass only onethird of gastrointestinal (GI) tract

• possible to achieve weight loss without predisposing patient to

nutritional deficiencies

Comparing Surgical Procedures

for Treatment of Obesity

•

•

•

What's the best choice: gastric bypass or gastric banding?

Bariatric surgery is the quickest fix for severe obesity, but patients must

carefully weigh benefits and risks before undergoing these invasive

procedures. Two reports in 2009 should provide some help with those

decisions.

In a prospective observational cohort study of perioperative complications (JW

Gen Med Jul 30 2009), researchers at 10 high-volume U.S. bariatric surgery

centers followed nearly 5000 patients who underwent open Roux-en-Y gastric

bypass, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, or laparoscopic adjustable

gastric banding. Thirty-day mortality was significantly higher with open

bypass than with the other two procedures (2.1% vs. 0.2% and 0%). Incidence

of a composite 30-day endpoint (death, venous thromboembolism, operative

reintervention, and prolonged hospitalization) was highest with open bypass,

intermediate with laparoscopic bypass, and lowest with banding (7.8%, 4.8%,

and 1.0%, respectively); this general pattern of complication rates persisted

after adjustment for baseline differences between groups. These researchers

currently are conducting a study of longer-term outcomes for 2400 patients

(LABS-2).

Adjustable gastric banding

• band on outside of stomach causes

narrowing

• swallowed food fills and stretches narrowed

upper stomach and sends signal to brain that

entire stomach full

• tubing connects to port placed

subcutaneously at midline, just off linea

alba

• band tightness adjusted in office by

injecting saline into port

Sleeve gastrectomy

• new procedure; excises about 80% of stomach

along greater curve

• involves neither caloric restriction nor

malabsorption

• removes hormonal mediators of hunger (eg,

ghrelin production virtually eliminated)

• patients never hungry and have no desire to eat

• avoids nearly all longterm complications of gastric

bypass or implant, including nutritional

deficiencies

• preliminary results show efficacy higher than band

and slightly lower than bypass; reduction in risk

probably worth benefit

Benefits of weight loss

surgery

• much safer than in past

• (mortality rate 0.5%)

• about same as other major surgery (eg,

vascular surgery)

Weight reduction

• gastric band—European and Australian

data show reduction of 50% to 60% of

excess weight;

• data not replicated in United States

• US data show 40% to 45% weight reduction

at 3 yr

• gastric bypass— reduction of 65% to 75%

of excess weight, mostly in first 18 mo

Diabetes, Hypertension, Sleep Apnea

• Diabetes: gastric band—type 2 diabetes improves

in about 70% of patients (complete resolution in

some)

• Diabetes: gastric bypass—>90% improvement

rate

• majority cured (usually immediately after surgery

and the reason not totally clear)

• Hypertension: gastric band—about 55%

improvement rate and possible cure

• gastric bypass—about 75% improvement rate and

possible cure

• Sleep apnea: cured in nearly all (98%-99%)

patients by both procedures

Risks

• intestinal leaking—can cause peritonitis

•

•

•

•

•

Increases death rate from 1 in 200 to 1 in 15

most leaks successfully managed

rarely occurs after banding

occurs in 1% of patients with bypass

pulmonary embolism—1% for both procedures

(recent reductions due to aggressive prophylaxis);

• death—nearly 0% with banding; 0.5% with

bypass

• reoperation rate—4% in both procedures; major

complications—5% after banding;

• 5% to 8% after bypass

Follow-up

• because of high number of annual procedures,

nearly every physician treats patients with history

of bariatric Surgery

• nonabdominal or nonbariatric GI issues addressed

as in patients without history of bariatric surgery

• for upper GI complaints in patient with band, first

deflate band

• done by primary care physician or bariatric

surgeon

• gastric cancer—uncommon, but likely to present

at advanced stage (patient complaining of pain)

Follow-up

• Biliary disease—endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

difficult in patients with history of bariatric

surger

• gastric bypass causes silent trauma to the

liver

• but improves or cures nonalcoholic

steatohepatitis (NASH)

• gastric bypass not recommended for

patients with active hepatitis B or C

• patient with biliary colic should be referred

for gallbladder removal

Complications

• early—patients with GI complications <60 days after

surgery should be sent back to bariatric surgeon

• most problems surgically related

• late complications after banding, most complications

implant-related (eg, infection, breakage, erosion, slippage)

• nausea, reflux, or vomiting indicative of complications and

should prompt emptying of band

• obtain x-ray

• after bypass, most commonly experienced complications

include internal hernia, strictures, and ulcers

• pain not normal after bypass

• Presence of pain suggestive of complications

• Intermittent cramping abdominal pain attributed to internal

hernia (most serious long-term complication) until proven

otherwise

Nutritional

deficiencies

• general malabsorption—food stream has

•

•

•

•

shorter transit time and less absorptive area

specific malabsorption—nutrient stream

does not contact specific areas of absorption

iron—after gastric bypass, 50% of

premenopausal women develop iron

deficiency anemia if not taking supplements

calcium—two-thirds have altered calcium

metabolism (likely vitamin D problem)

thiamine – uncommon, but serious; may

result in peripheral neuropathy (usually

irreversible)

Beriberi

• Beriberi is a neurological and cardiovascular disease. The three major

forms of the disorder are dry beriberi, wet beriberi, and infantile

beriberi.[14]

• Dry beriberi is characterized principally by peripheral neuropathy

consisting of symmetric impairment of sensory, motor, and reflex

functions affecting distal more than proximal limb segments and

causing calf muscle tenderness.[29]

• Wet beriberi is associated with mental confusion, muscular wasting,

edema, tachycardia, cardiomegaly, and congestive heart failure in

addition to peripheral neuropathy.[2]

• Infantile beriberi occurs in infants breast-fed by thiamin-deficient

mothers (who may show no sign of thiamine deficiency). Infants may

manifest cardiac, aphonic, or pseudomeningitic forms of the disorder.

Infants with cardiac beriberi frequently exhibit a loud piercing cry,

vomiting, and tachycardia.[14] Convulsions are not uncommon, and

death may ensue if thiamine is not administered promptly.[29]

• Following thiamine treatment, rapid improvement occurs generally

within 24 hours.[14] Improvements of peripheral neuropathy may

require several months of thiamine treatment.

Alcoholic brain disease

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Nerve cells and other supporting cells (such as glial cells) of the nervous system require thiamine. Examples of

neurologic disorders that are linked to alcohol abuse include Wernicke’s encephalopathy (WE, Wernicke-Korsakoff

syndrome) and Korsakoff’s psychosis (alcohol amnestic disorder) as well as varying degrees of cognitive

impairment.[33]

Wernicke’s encephalopathy is the most frequently encountered manifestation of thiamine deficiency in Western

society,[34] though it may also occur in patients with impaired nutrition from other causes, such as gastrointestinal

disease,[34] those with HIV-AIDS, and with the injudicious administration of parenteral glucose or hyperalimentation

without adequate B-vitamin supplementation.[35] This is a striking neuro-psychiatric disorder characterized by

paralysis of eye movements, abnormal stance and gait, and markedly deranged mental function.[36]

Alcoholics may have thiamine deficiency because of the following:

inadequate nutritional intake: alcoholics tend to intake less than the recommended amount of thiamine.

decreased uptake of thiamine from the GI tract: active transport of thiamine into enterocytes is disturbed during acute

alcohol exposure.

liver thiamine stores are reduced due to hepatic steatosis or fibrosis.[37]

impaired thiamine utilization: magnesium, which is required for the binding of thiamine to thiamine-using enzymes

within the cell, is also deficient due to chronic alcohol consumption. The inefficient utilization of any thiamine that

does reach the cells will further exacerbate the thiamine deficiency.

Ethanol per se inhibits thiamine transport in the gastrointestinal system and blocks phosphorylation of thiamine to its

cofactor form (ThDP).[38]

Korsakoff Psychosis is generally considered to occur with deterioration of brain function in patients initially

diagnosed with WE.[39]. This is an amnestic-confabulatory syndrome characterized by retrograde and anterograde

amnesia, impairment of conceptual functions, and decreased spontaneity and initiative.<[29]

Following improved nutrition and the removal of alcohol consumption, some impairments linked with thiamine

deficiency are reversed; particularly poor brain functionality, although in more severe cases, Wernicke-Korsakoff

syndrome leaves permanent damage.

Nutritional deficiencies

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) deficiencies develop slowly

vitamin B12 requires laboratory testing

30% of bariatric procedure patients deficient in vitamin B12

most asymptomatic