questionnaires

advertisement

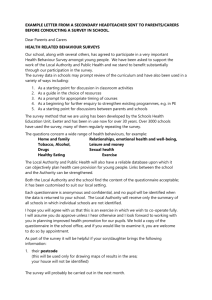

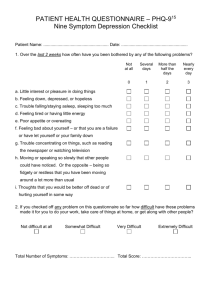

QUESTIONNAIRES © LOUIS COHEN, LAWRENCE MANION, AND KEITH MORRISON STRUCTURE OF THE CHAPTER • • • • • • • • • • • • • Ethical issues Approaching the planning of a questionnaire Types of questionnaire items Asking sensitive questions Avoiding pitfalls in question writing Sequencing questions Questionnaires containing few verbal items The layout of the questionnaire Covering letters/sheets and follow-up letters Piloting the questionnaire Practical considerations in questionnaire design Administering questionnaires Processing questionnaire data ETHICAL ISSUES • • • • • • • • • • Intrusion Informed consent Rights to withdraw at any stage or not to complete particular items Beneficence Non-maleficence Confidentiality, anonymity and non-traceability Threat or sensitivity Avoidance of bias Validity and reliability in the questionnaire Reactions of the respondent APPROACHING THE PLANNING OF A QUESTIONNAIRE • Stage One: Decide the purposes/objectives/ research questions; • Stage Two: Decide the population and sample • Stage Three: Itemize the topics/constructs/ concepts; • Stage Four: Decide the kinds of measures or responses needed; • Stage Five: Write the questionnaire items; • Stage Six: Check that each research question has been covered; • Stage Seven: Pilot the questionnaire and refine; • Stage Eight: Administer the questionnaire. OPERATIONALIZING A QUESTIONNAIRE • Clarify the questionnaire’s general purposes and then translate them into a specific, concrete aim or set of aims. • Identify and itemize subsidiary topics that relate to its central purpose. • Formulate specific information requirements relating to each issue. • Plan with the data analysis in mind. STRUCTURED, SEMI-STRUCTURED AND UNSTRUCTURED QUESTIONNAIRES • The larger the size of the sample, the more structured, closed and numerical the questionnaire may have to be. • The smaller the size of the sample, the less structured, more open and word-based the questionnaire may be. • Structured questions take a lot of time to set up but then a short time to process and analyze. • Open questions take a shorter time to set up but a longer time to process and analyze. TYPES OF QUESTION • Open to closed • Choose the metric (scale of data): – Nominal – Ordinal – Interval – Ratio • Do not assume that respondents have the information/knowledge/views TYPES OF QUESTION DICHOTOMOUS YES/NO MULTIPLE CHOICE ONE/MANY RESPONSES RATING SCALES ODD/EVEN NUMBERS OPEN-ENDED FREE RESPONSE TYPES OF QUESTION RANKING 1st/2nd. ETC. RATIO DATA MANY RESPONSES CONSTANT SUM DISTRIBUTING MARKS RATIO DATA MARKS OUT OF TEN DICHOTOMOUS QUESTIONS • Good for clear answers; • Yes/no questions are often better rephrased as ‘to what extent’ or ‘how much’ types of question. MULTIPLE CHOICE • Need for a pilot to gather exhaustive categories of response; • Do not allow for range of response; • If more than one response permitted then each choice is a separate variable. • • • • • • • • • LIKERT SCALES Useful for measuring degrees of intensity of feeling; No assumption of equal intervals; No assumptions of matched intensity of feeling; No way of knowing if respondents are telling the truth; No way of knowing if there should be other categories or items; Halo effect; Allows for different scaling and mid-points, e.g.: (a) strongly disagree – neither agree nor disagree – strong agree; (b) not at all – a very great deal; Central tendency; Ordinal data. SEMANTIC DIFFERENTIAL SCALES • A word and its semantic opposite, e.g.: – Approachable . . . unapproachable – Generous . . . Mean – Friendly . . . hostile • Same concerns as for Likert scales. OPEN-ENDED QUESTIONS • Enable authentic responses; • More time-consuming and difficult to analyze/process. RANKING SCALES • Enables comparisons to be made by respondents across items; • Enables sensitivity of response to be addressed; • Can be ‘strong on reality’ of decision making; • Too many items to rank may result in unrealistic ranking (people may not have strong enough opinions to be able to rank) • Too many decisions to be made; • Ordinal data. RATIO DATA: MANY RESPONSES • Avoids forcing responses into categories; • Allows for very great accuracy (e.g. ‘how old are you?’) • Ratio data: mean, standard deviation, median CONSTANT SUM • Divide a fixed number of points between a range of items; • Yields priorities, comparative highs and lows and equality of choice quickly and easily – in the respondents’ own terms; • Requires participants to make comparative judgements and choices across items; • May be too difficult if there are too many items across which to spread marks; • People may make computational errors in distributing marks; • Ordinal data. RATIO DATA: MARKS OUT OF TEN • Enables proportions/ratios to be calculated; • Enables high level statistics to be computed, e.g. regression, factor analysis, structural equation modelling. ASKING SENSITIVE QUESTIONS • Use open rather than closed questions about socially undesirable behaviour. • Use long rather than short questions about socially undesirable behaviour. • Use familiar words when asking about socially undesirable behaviour. • Use data from informants. • Deliberately load questions so that overstatements of socially desirable behaviour and understatements of socially undesirable behaviour are reduced. • With regard to socially undesirable behaviour, firstly ask whether the respondent has engaged in that behaviour previously, and then move to asking about current behaviour. ASKING SENSITIVE QUESTIONS • Locate sensitive topics within a discussion of other less sensitive matters. • Use alternative ways of asking standard questions. • Ask respondents to keep diaries. • At the end of an interview ask respondents their views on the sensitivity of the topics that have been discussed. • Find ways of validating the data. • As questions become more threatening and sensitive, expect greater bias and unreliability. ‘RULES’ FOR QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN (1) • Ensure that each issue is explored in more than one question; • Decide the most appropriate kind of question and the kind of scale; • Plan with the kind of analysis in mind; • Avoid leading questions: ‘Do you prefer abstract, academic-type courses, or down-to-earth, practical courses that have some benefit in day-to-day work?’ • Ensure that the question stem does not frame the answer: ‘The tourism industry is successful because . . . .’. ‘RULES’ FOR QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN (2) • Avoid highbrow questions: ‘What particular aspects of the current positivistic/interpretive debate would you like to see reflected in the course of developmental psychology?’ • Avoid negatives and double negatives: ‘How far do you agree that without a Consumer Association the public cannot discuss consumer matters?’ • Avoid complex questions: ‘Would you prefer a short award-bearing course with part-day release and one evening per week attendance, or a longer, nonaward-bearing course with full-day release, or the whole day designed on part-day release without evening attendance?’ • Avoid too many open-ended questions on selfcompletion questionnaires ‘RULES’ FOR QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN (3) • Try to convert dichotomous questions into rating scales: ‘Do you. . .’ / ‘Are you. . .’ become ‘How far . . .?’/ ‘How much . . .?’ • Provide anchor statements for rating scales; • Have a minimum five-point rating scale if you opt for uneven numbers; • Decide whether to have odd or even numbered rating scales; • Avoid extremes in rating scales ( e.g. ‘always’, ‘never’) • Avoid too many open-ended questions in large surveys; ‘RULES’ FOR QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN (4) • Only ask one thing at a time: Avoid: ‘how much do you think Business courses should be available to all students, or should they only be available to higher ability students?’ • Avoid ambiguity: ‘Are your parents in employment?’ ‘Have you done your homework this week?’ Do you do your homework regularly?’ ‘How many staff are there in your institution?’ How many computers does your institution have?’ • Avoid threatening/irritating questions: ‘How frequently do you drink alcohol each week?’ ‘RULES’ FOR QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN (5) • Clarify the kind of response sought in an open-ended question: ‘Please indicate the most important factors that reduce staff participation in decision making.’ • Start with simple factual questions and then move to more sensitive questions; • Provide instructions for how to complete and return the questionnaire; • Have a cover sheet which explains the purposes of the questionnaire and which sets out ethical issues. ‘RULES’ FOR QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN (6) • Ensure categories are mutually exclusive and comprehensive (covering all possible choices of response); • Avoid pressurising/biasing by association: e.g. ‘do you agree with your school principal that boys are more troublesome than girls?’ • Have translations verified/use back translation; • Keep it as short, simple and clear as possible; • Pilot the questionnaire. SEQUENCING QUESTIONS • Take care with order effects – Earlier responses affect later responses – Early tone/mood-setting affects later moods in completing questionnaires • Primacy effect – Items high in a list tend to be chosen more than items lower in a list – Respondents choose the first reasonable answer from a list, even though a later response statement might be more fitting • Avoid placing sensitive questions at the start – Embed them later questions • Move from objective facts to subjective views QUESTIONNAIRES CONTAINING FEW VERBAL ITEMS • A questionnaire might: – include visual information and ask participants to respond to this (e.g. pictures, cartoons, diagrams) – might include some projective visual techniques (e.g. draw a picture or diagram) – join two related pictures with a line, write the words or what someone is saying or thinking in a ‘bubble’ picture THE LAYOUT OF THE QUESTIONNAIRE • • • • • • • It must look easy, attractive and interesting. Keep it as uncomplicated as possible. Clarity of wording. Simplicity of design. Simple, short and clear instructions for completion. Avoid placing instructions at the bottom of a page. Break down long lists of numbered items into separate sections, each item in the section starting with the number ‘1’. • Make it clear if respondents are exempted from completing certain questions or sections (filter), and where they go next if they are exempted. • Include a preliminary statement of anonymity/confidentiality. • Place response categories to the immediate right of the text. THE COVERING LETTER SHOULD . . . • • • • • • • • Provide a title to the research; Introduce the researcher and contact details; Indicate the purposes of the research; Indicate the importance and benefits of the research; indicate why the respondent has been selected for receipt of the questionnaire; Indicate any professional backing, endorsement, or sponsorship of, or permission for, the research; Set out how, where and by what date to return the questionnaire; Indicate what to do if questions or uncertainties arise; THE COVERING LETTER SHOULD . . . • • • • Indicate any incentives for completing the questionnaire; Provide assurances of confidentiality, anonymity and non-traceability; Indicate how the results will and will not be disseminated, and to whom; Thank respondents in advance for their cooperation. PURPOSES OF PILOTING • • • • • • • • • • To check clarity of items/layout/sections/presentation/ instructions; To gain feedback on appearance; To eliminate ambiguities/uncertainty/poor wording; To check readability; To gain feedback on question type (suitability/feasibility/ format (e.g. open/closed/multiple choice); To gain feedback on appropriateness of question stems; To generate categories for responses in multiple choices; To generate items for further exploration/discussion; To gain feedback on response categories; To gain feedback on length/timing (when to conduct the data collection as well as how long each takes to complete (e.g. each interview/questionnaire))/coverage/ease of completion; PURPOSES OF PILOTING • • • • • • • • • • To identify redundant items/questions (those with little discriminability); To identify irrelevant questions; To identify non-responses; To identify how motivating/non-engaging/threatening/ intrusive/offensive items may be; To identify sensitive topics and problems in conducting interviews; To test for inter-rater reliability; To minimise counter-transference; To gain feedback on leading questions; To identify items which are too easy/difficult/complex/ remote from experience; To identify commonly misunderstood or non-completed items. PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN • Operationalize the purposes of the questionnaire. • Be prepared to have a pre-pilot to generate items for a pilot questionnaire, and then be ready to modify the pilot questionnaire for the final version. • If the pilot includes many items, and the intention is to reduce the number of items through statistical analysis or feedback, then be prepared to have a second round of piloting, after the first pilot has been modified. • Decide on the most appropriate type of question – dichotomous, multiple choice, rank orderings, rating scales, constant sum, ratio, closed, open. • Ensure that every issue has been explored exhaustively and comprehensively; decide on the content and explore it in depth and breadth. • Use several items to measure a specific attribute, concept or issue. PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN • Ask more closed than open questions for ease of analysis (particularly in a large sample). • Balance comprehensiveness and exhaustive coverage of issues with the demotivating factor of having respondents complete several pages of a questionnaire. • Ask only one thing at a time in a question. Use single sentences per item wherever possible. • Keep response categories simple. • Avoid jargon. • Keep statements in the present tense wherever possible. • Strive to be unambiguous and clear in the wording. • Be simple, clear and brief wherever possible. • Clarify the kinds of responses required in open questions. PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN • Balance brevity with politeness, e.g. replace a blunt phrase like ‘marital status’ with a gentler ‘please indicate whether you are married, living with a partner, or single....’. • Ensure a balance of questions which ask for facts and opinion. • Avoid leading questions. • Try to avoid threatening questions. • Do not assume that respondents know the answers, or have information to answer the questions, or will always tell the truth (wittingly or not).. • Avoid making the questions too hard. • Balance the number of negative questions with the number of positive questions. • Consider the readability levels of the questionnaire and the reading and writing abilities of the respondents. • Put sensitive questions later in the questionnaire. • Intersperse sensitive questions with non-sensitive questions. PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS IN QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN • Be very clear on the layout of the questionnaire so that it is unambiguous and attractive. • Avoid, where possible, splitting an item over more than one page,. • Ensure that the respondent knows how to enter a reply to each question. • Pilot the questionnaire. • With the data analysis in mind. • Decide how to avoid falsification of responses. • Be satisfied if you receive a 50 per cent response to the questionnaire • Decide what you will do with missing data. • Include a covering letter. • If the questionnaire is going to be administered by someone other than the researcher, ensure that instructions for administration are provided and that they are clear. METHODS OF ADMINISTERING QUESTIONNAIRES • • • • • • • Post Self-administration in presence of researcher Self-administration without researcher present In situ completion (e.g. workplace/ home) Face-to-face interview Telephone Internet PROCESSING QUESTIONNAIRE DATA • Coding • Data reduction techniques • Editing and cleaning data