ppt file - Department of Psychology

Organizational and

Methodological Issues in

Large-Scale Cross-National

Research: UN or NATO

Approach?

Juan I. Sanchez

Florida Int’l University

Paul E. Spector

University of South

Florida

Prepared for:

2009 MSU Symposium on Multicultural Psychology “Conducting

Multinational Research Projects in Organizational Psychology:

Challenges and Opportunities”

October 11-12, 2009

1

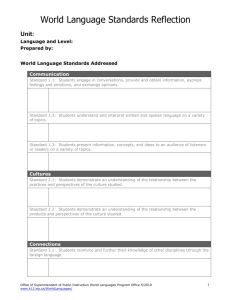

Sample Cross-Cultural/Cross-National – CC/CN - Publications

Bonache, J., Sanchez, J. I., & Zarraga-Oberty, C. (in press). The interaction of expatriate pay differential and expatriate inputs on host country nationals’ pay unfairness.

International Journal of Human Resources Management .

Sanchez, J. I., Gomez. C., & Wated, G. (2008). A value-based framework for understanding managerial tolerance of bribery in Latin America.

Journal of Business Ethics,

83(2), 341-352.

COLLABORATIVE INTERNATIONAL STUDY OF MANAGERIAL STRESS (CISMS):

Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., Sanchez, J. I., O’Driscoll, M., Sparks, K., et al. (2002).

Locus of control and well-being at work: How Generalizable Are Western Work Findings?

Academy of Management Journal, 45, 453-470.

Spector, P. E., Cooper, C. L., Sanchez, J. I., O’Driscoll, M., Sparks, K., et al. (2001).

Do national levels of individualism and internal locus of control relate to well-being: An ecological level international study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(8), 815-832.

Sanchez, J. I., Spector, P. E., & Cooper, C. L. (2000). Adapting to a boundaryless world: A developmental model of the expatriate executive. Academy of Management

Executive, 14(2),96-106.

2

Outlet

CC/CN Research Publications

Number of articles

Academy of Management Executive

Academy of Management Journal 1

Applied Psychology: An Int’l Review 1

Group and Organization Management

Human Resource Management

International Journal of Cross-Cultural Mgmt.

Int’l Journal of HRM

Int’l Journal of Organizational Analysis

Int’l Journal of Stress Management 1

Journal of Business Ethics

Journal of Organizational Behavior 1

Journal of Vocational Behavior 1

Personnel Psychology 1

1 1

1 1

2 1

1

2 1

1

3

2

1

1

1

1 1

3 1

1 Large-scale cross-cultural research where n > 5, 000 AND no. of countries > 20 3

Basic research question

Do organizational behavior theories developed primarily in

English-speaking countries transfer to other cultural settings?

Culture-general (etic)?

X Y

Culture-specific (emic)?

X

Y

4

Basic research question (Continued)

B

C

D

Country r

xy

A .06

.23

.12

.39

Variation due to culture?

B

C

D

Country r

xy

A .06

.23

.12

.39

Variation due to third variable confounds and statistical artifacts?

Organizational

Methodological

5

Basic research question (Continued)

Organizational choices -> a high degree of control over methodological issues -> adequate progression of research.

Our relatively centralized, goal-oriented approach to the organization of these studies contrasts with a decentralized one (we have tongue-in-cheek labeled these as the “NATO” and the “UN” approach, respectively).

North Atlantic Treaty Organization United

Nations

6

Organizational Issues in CC/CN Research (Continued)

Selection of Researchers .

Based on our experience with CISMS 1, we decided to classify the participating researchers in CISMS 2 in two groups:

A

core group

of researchers who participated in the choice of scales to be included in the survey, the design of the study, and the formulation of broad research goals and objectives.

history of prior collaboration/trust well-published in English-language journals

A group of research collaborators who handled primarily data collection in a specific country, and who in several cases went on to conduct within-country studies or smaller scale between-country comparisons.

7

Organizational Issues in CC/CN Research (Continued)

Pre-study contract . All participating researchers agreed to a “contract” or set of written rules that specified the obligations and rights of each participant.

Most important: Rules regarding authorship.

*Each participating researcher agreed to run their manuscripts by all the members of the core group, and to include their names as co-authors in any resulting manuscripts after incorporating their feedback into the manuscript.

*The order of authorship was determined according to effort and contribution and, when these were similar in magnitude, by alphabetical order.

8

Organizational Issues in CC/CN Research (Continued)

Leadership model . rules for participation and authorship made the study relatively easy to manage.

Core group -> impetus for CISMS: They were instrumental in recruiting other researchers.

All participating researchers were asked to send the data in electronic form to the central team, but in some cases –especially during CISMS 1- they sent the questionnaires and the data were entered by the central team.

Instructions regarding data entry were provided to all participating researchers. When issues or questions about the data arose during data entry, the central team contacted the specific researcher.

9

Organizational Issues in CC/CN Research (Continued)

The issues encountered ran the gamut…

* A participating researcher from an Islamic country who, upon learning that the study included data from Israel, decided to withdraw from the study –she alleged her withdrawal was a matter of personal security...

* Endless exchanges and warnings for and against calling Taiwan a

“country”… the word “territory” came in handy…

10

1.

2.

Methodological Issues in CC/CN Research

Focus on two types of confounds that may diminish the researchers’ certainty regarding cultural effects:

Carefully done translations may not necessarily result in equivalent instruments, despite back-translation (Brislin, 1986).

Valid conclusions about culture effects require samples that present minimal differences beyond their differing cultures, but there are numerous factors potentially confounded with culture: task policies welfare state socialized medicine emerging economy…

11

Methodological Issues: Measurement Equivalence

Is measurement equivalence between translated instruments possible?

Two schools of thought…

Nonequivalence is due to poor translation…

Nonequivalence is due to the Sapir-Whorf or Whorfian hypothesis (Werner & Campbell, 1970) -> language is thought to filter the evaluative, connotative, and affective meaning of scale items, thereby preventing comparisons between linguistically different groups.

12

Video-clip:

The German Coast Guard

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8vBn2_ia8zM

13

Methodological Issues: Back-translation

Translating the measure to the target language first, independently translating it back to the source language, and comparing the two versions to ascertain linguistic problems in the translation (Brislin, 1986).

Nevertheless, back-translations do not necessarily guarantee measurement

equivalence. B ack-translators share knowledge that may lead them to consider terms as if they were synonyms whereas respondents do not see them that way (e.g.,

“simpático” in Spanish and “friendly” in English may not always mean the same thing, but translators may see them that way due to their learned semantic connection between the two languages).

back-translations may retain the grammar and idiomatic expressions of the source language, which may be easy to back-translate but may not have the same meaning to monolinguals in the target language . For example, an item developed for a Chinese scale (i.e., “one should not be afraid of the change of heavens”), which measured beliefs of control in China was successfully back-translated from English to Chinese, but it obviously lacks unambiguous meaning for English-speaking monolinguals (Siu & Cooper, 1998).

14

Methodological Issues: Back-translation (Continued)

Differences in item calibration:

an individual who agrees with the item, "I am sometimes tense at work", will not necessarily endorse a more extremely worded item like "I sometimes find myself in panic at work." The reason is that, even though both items reflect anxiety, they symbolize different degrees of the anxiety construct.

1.

Culture may

enhance

this effect: A participant from India, for example, might not see an item as representing the exact same degree of the construct than an Australian counterpart.

2.

If we

cross languages

, the problem becomes

worse

.

Consider an item that reads "I love my job." A linguistically correct Spanish translation of this item will be "Yo amo mi trabajo." However, the verb "amar"

(to love) in Spanish is usually confined to people, and it is seldom or never used to refer to things or social constructs like a job.

15

Methodological Issues: Back-translation (Continued)

Anchor equivalence:

finding equivalent anchors for the

extreme

points of the scale is relatively

easy

, but finding equivalent anchors for the

mid-points

can be

tricky

.

For instance, a suitable Spanish translation of “very much agree” would be

“muy de acuerdo,” but translating the mid-anchor “agree slightly” is not straightforward because the exact degree conveyed by the word “slightly” does not have an unequivocal synonym in Spanish…

Example:

Consider what it means to be “slightly late” in different cultures...

16

Methodological Issues: Back-translation (Continued)

Back-translation is an “art,” not a science:

Inattention to measurement criteria pervades back-translation procedures.

There are no clear guidelines for deciding when is a back-translated scale sufficiently close to the original version, as this decision is usually left to the translators’ professional judgment.

17

Methodological Issues: Scale reliability

Reliability:

Consider the mean alpha reliability coefficient across 26 scales related to work stress was:

.69

Spain

Similar level of reliability than the original English scales employed in the U.K. and the U.S.

.70

.75

UK

US

A LISREL comparison of the var-cov structures of Spector’s (1988) Work Locus of

Control Scale between the U.K. and Spanish samples suggested that inter-item relationships differed between the two countries:

In Spain, the item “if you know what you want out of a job, you can find a job that gives it to you” had practically null correlations with most of the other scale items (median r = .10).

In the U.K. this item had generally larger and statistically significant correlations with other items in the scale (median r = .23). This differential item functioning should not be surprising to anyone familiar with the relatively high levels of unemployment in Spain.

An apparently adequate level of reliability does not necessarily constitute a sign of the equivalence between the original and the translated instrument.

18

Methodological Issues: Construct equivalence

A given construct might

manifest itself differently

across countries/cultures, so that different items would be needed to capture its unique cultural nuances (Lonner, 1990).

Construct equivalence has received far less attention that measurement equivalence, but it is probably a more important issue…

Example: Stress Research

direct disagreements among employees might be more likely to be perceived as interpersonal conflict among Chinese for whom group harmony is an important value than among Americans who are less sensitive to direct confrontation.

in an analysis of stressful work incidents, Americans were more likely to have direct conflicts with others, whereas Chinese were more likely to have indirect.

When asked to describe a stressful incident at work, Americans but not Indians reported instances of lack of control and work overload, whereas Indians but not Americans reported instances of lack of structure and equipment/situational constraints (Narayanan, Menon &

Spector, 1999). The most often noted stressor for Americans and Indians was opposite—too little control for one and too little direction for the other.

19

Methodological Issues: Response Biases

Culture/national differences in response biases or tendencies (Triandis,

1994b; van de Vijver & Leung, 1997) –e.g., people from some countries preferring extreme responses and others avoiding them.

These tendencies might be more complex than previously thought:

Compared to Americans, Japanese avoided reporting extreme positive feelings, but not extreme negative ones (Iwata, Umesue, Egashira,

Hiro, Mizoue, Mishima, and Nagata, 1998).

Differences in response tendencies are NOT equivalent across all scales or even all items within a scale (Iwata et al., 1998).

Finally, we cannot be certain that a given difference can be attibutable to response tendencies just because one group usually scores higher or lower than others.

Did the Japanese in the Iwata et al. (1998) study avoid extreme positive reports because of cultural modesty tendencies, or because they experienced less positive affect than Americans?

20

Research designs that analyze/control language effects

Because back-translation does not guarantee the absence of language effects on cross-cultural comparisons, research designs have been employed to control or analyze for them...

(1)between-participant comparisons across languages that hold culture constant, such as for example comparing the English and French versions of a measure using samples from the same nation (e.g., Canadians) (Candell & Hulin, 1987),

(2)between-participant comparisons across cultures holding language constant, such as, for instance, comparing U.S. versus Australian samples (Ryan, Chan, Ployhart, &

Slade, 1999),

(3)Use bilinguals in within-participant comparisons of responses in different languages (Hulin, Drasgow, & Komocar, 1982; Katerberg, Hoy, & Smith, 1977;

Rybowiak, Garst, Frese, & Batinic, 1999).

21

Research designs that analyze/control language effects (Continued)

Each one of these approaches has limitations…

(1)between-participant comparisons across languages that attempt to hold culture constant may not succeed due to self-selection.

Take for instance the case of a sample of 1,931 Canadians enlisted in the Canadian Armed Forces used by

Candell and Hulin (1987). The 235 French-Canadians who responded in English might have been more acculturated to the patterns of English-speaking Canada than those who chose the French version and, therefore, culture was in part confounded with language in comparing these two groups of French Canadians.

(2)between-participant comparisons across cultures that hold language constant (e.g., Australia vs. U.S.; Brazil vs. Portugal) are still influenced by sample differences in third variables that are often confounded with nation.

For instance, a public notary typically enjoys a much higher social status in Europe than in the U.S., and therefore comparing public notaries across countries may yield differences associated with third variable effects rather than with culture. We further elaborate on this issue on the section entitled “Sample Equivalence Between Cultures” included later in this chapter.

(3)Use bilinguals in within-participant comparisons: multilinguals may differ from monolinguals both culturally and linguistically.

22

Use bilinguals in within-participant comparisons

Bilingualism vs. Biculturalism of Translators.

Although translators may be linguistically competent, their ability to ascertain cultural nuances in the manifestation of stress across cultures may be limited.

Translators should be carefully selected according to not only their linguistic competence, but also the extent to which they are truly “bicultural” individuals familiar with the subtleties inherent in the ways in which individuals in the two cultures express their attitudes and emotions.

A linguistically imperfect translation may provide better psychological equivalence than a linguistically perfect one. Example:

The Spanish term “de pronto,” whose linguistically correct English translation will be “all of a sudden,” is often used in some Latin American countries located in the Andean cordillera to mean “perhaps” or “maybe.” A linguistically competent Spanish-English translator may fail to realize this colloquial usage of the term, hence rendering a technically correct but nonequivalent translation of an item including this term.

23

Use bilinguals in within-participant comparisons (Continued)

Check for cultural accommodation or “Whorfian” responding (Bond & Yang,

1982) -> does the same bilingual respondent give different answers to the two versions of the same measure?

Consider order effects in the presentation of the two versions of the same measure. Consider counterbalancing and/or analyzing order of language administration.

Considering controlling (or better yet measuring) language proficiency amongst bilinguals.

24

Multi-Cultural Scale Development Procedures

Even if the items are successfully translated linguistically, there exists the possibility that the individual items don’t do a good job of reflecting the construct universally –ethnocentric scale development.

A procedure to help eliminate this problem is to enlist researchers in multiple countries to have input into scale development from the beginning.

25

Multi-Cultural Scale Development Procedures (Continued)

The team goes through a multi-stage procedure for scale development that is more complex than the typical process

( Spector, Sanchez, Siu, Salgado, & Ma, 2004):

(1)a clear definition of the construct of interest is discussed and written so everyone has a similar understanding of what the items should reflect.

(2)each team member independently writes a set of scale items.

(3)the items are mixed up and compiled into a questionnaire that is administered to a sample of subjects. This can be done in multiple countries. Item and factor analysis are applied to select the final items.

(4)validation studies should be conducted in multiple countries, although it should be kept in mind that relationships between the construct of interest and other constructs might vary across culturally dissimilar countries.

26

Sample Equivalence Between Cultures

One problem in much cross-cultural stress research is the availability of equivalent participant samples:

We often compare individuals who vary, not only in country, but in demographics such as occupation, income (relative to society) and status. Even within the same occupation, differences in work conditions can masquerade as cultural differences.

Suppose we compare physicians in the U.S. versus those in a country with socialized medicine. If we find the Americans are more highly stressed, should we conclude that the U.S. is a more stress-producing culture?

Clearly, with so many potential third-variable effects, we need to be extremely careful to match subjects on as many relevant variables as possible, so that we are able to attribute differences to culture.

27

Sample Equivalence Between Cultures (Continued)

However, matching participants in all potential third-variables so that one ends up with comparable samples across countries is farfetched because of wide variation across cultures. For researchers who study employed populations, economic and social factors can make it difficult to identify equivalent samples.

Example:

In contrast to North America, there are countries where large private corporations are rare. In other countries, state-managed enterprises dominate the economic landscape and, therefore, even matching for industry sector will not rid comparisons of selection bias, because organizations in the same sector (e.g., oil production and distribution) will still differ in meaningful ways like whether they are private or state-run enterprises. Even those who study college students might find differences across countries. In the U.S. a far greater proportion of the general population attends college than in countries where college attendance tends to be limited to the upper echelons of society.

->Thus, statistically controlling for factors representing rival explanations seems necessary even in the best of matched samples.

28

Sample Equivalence Between Cultures (Continued)

One should try to match on variables likely to cause confounded results.

Because matching is often unfeasible ->gather as much information as possible about the samples; this info can be used later on as controls.

We should carefully examine economic (e.g., relative standard of living, economic system, and tax structure), political, and social factors. For research conducted in organizations, data on industry sector, organizational structure, and power structure should be collected. Example:

Have samples of American physicians from different settings, such as private practice versus public health facilities. If the Americans, regardless of setting, score higher on the stressor measures than the Chinese, one gains confidence that results might be due to culture. As one compares more and more occupations and continues to find the same results, one begins to establish a pattern of cultural differences.

29

Sample Equivalence Between Cultures (Continued)

In choosing control variables, researchers should be careful about operationalizing such measures in terms of subjective appraisals.

Example 1: A majority of measures of social support rely on subjective appraisals of received support (Viswesvaran, Sanchez, & Fisher, 1999). Reports of social support are influenced by the extent to which societies are collectivistic vs. individualistic

(Triandis, 1994) and, therefore, matching samples on the extent to which individuals feel that they had support from supervisors, co-workers, or even family members ignores variations on what various cultures would consider an adequate level of support .

Example 2: Appraisals of perceived workload are likely to differ as a function of culture:

No. of work hrs.

Perceived workload culture

30

Conclusion

Globalization will continue to make cross-cultural comparisons more important than ever…

… and yet total measurement equivalence between instruments employed in cross-cultural comparisons may not be possible (Byrne & Watkins, 2003).

Research procedures and measurement tools that minimize measurement and sampling error in cross-cultural comparisons are needed to increase our understanding of cultural nuances, which should increase the cross-cultural generalizability of our theories.

31

Thank you!

Contact info:

Juan I. Sanchez, Ph.D.

Professor and Knight-Ridder Byron Harless Eminent Chair in Management

Department of Management and International Business

Florida International University

University Park

Miami, FL 33199

(305) 348-3307 sanchezj@fiu.edu

32