Claims & Critical Thinking: Presentation

advertisement

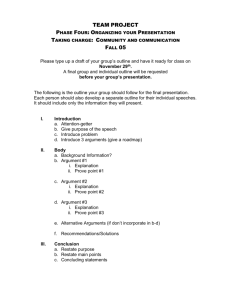

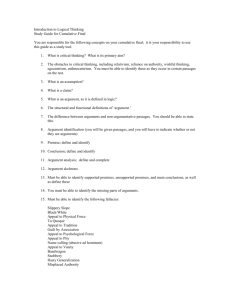

Claims and Critical Thinking Claims are either true or false. Some sentences (even some nondeclarative ones) make claims, but some (even some declarative ones) do other things. CRITICAL THINKING: The careful, deliberate determination of whether to accept, reject, or suspend judgment about a claim – and the degree of confidence with which we accept or reject it. Skills Beneficial to Everyone Critical thinking is not about attacking and defeating others; it’s about helping them and you. Critical thinking is more a set of skills than a set of facts. Skills Involved in Critical Thinking Careful listening and reasoning Finding hidden assumptions Tracing the consequences of claims Determining the credibility of sources Recognizing and avoiding various sorts of rhetoric and pseudoreasoning Analyzing and evaluating arguments Issues Issue: a matter of controversy or uncertainty. Issues may be internal (between self and self) or external (between self and others.) Topics of conversation aren’t issues unless there is controversy or uncertainty that the parties are trying to resolve. Critical thinking requires identifying the issue, separating it from others and focusing on it. Issues should be kept straight and dealt with in proper order (efficiently.) Arguments Arguments are one of the ways used to settle issues. Arguments attempt to support a claim (the conclusion) by giving reasons for believing it (the premises.) The issue is “Whether or not the conclusion is acceptable given the premises.” Facts and Opinions “Fact” indicates that a claim is true. “Opinion” indicates that a claim is believed. Clearly, some opinions are factual and some aren’t. Objectivity and Subjectivity An issue is factual or (objective) if there are accepted means for settling it. An issue is a matter of pure opinion (subjective) if both sides could be correct. Objective claims are true or false regardless of our inner states while subjective claims are usually just expressions of inner states. Controversy alone does not make an issue subjective; equality of persons doesn’t mean equality of opinions. Disputes may arise over whether certain types of claims (e.g., moral ones) are objective or subjective. Organizing an Argumentative Essay Make the focus clear at the beginning. Stick to the issue. Arrange the elements in a logical order. Be complete (easier with limited topics.) Good Writing Habits Outline after the first draft. Revise, revise, revise! Let others read and criticize. Read it out loud. When satisfied, put it aside for a while then revise again! Essays to Avoid Windy preamble essays. Rambling stream-of-consciousness essays. Knee-jerk reaction essays. Glancing-blow essays. Let-the-reader-do-the-work essays. Clarity I: Definitions A definition can serve different purposes: to stipulate, to explain, to precise and to persuade. Definitions can be by example, by synonym or analytical (genus-species). Abstract terms may not be completely definable. The literal meaning of a term is distinct from its emotive force (the denotation is distinct from the connotation.) Clarity II: Ambiguity Ambiguous claims have more than one meaning in the context. In semantical ambiguity, specific words or phrases have multiple meanings. In syntactical ambiguity, the entire structure of the sentence is at fault. In grouping ambiguity, it isn’t clear whether we are talking about the members of a group collectively or individually. Composition and Division Fallacies A composition fallacy occurs when we argue that what holds true individually must hold true collectively. A division fallacy occurs when we argue that what holds true collectively must hold true individually. Clarity III: Vagueness A claim is vague if it doesn’t have a precise enough meaning in the context. Vagueness is a matter of degree. Fuzzy words (“old”, “bald”, “rich”) can produce vagueness, but you can be vague even without them. Clarity IV: Comparative Claims Is important information missing? Is the standard of comparison clear? Is the same standard being used? Are the same reporting and recording practices being used? Are the items really comparable? Is the comparison an average and, if so, what kind (mean, median or mode)? When Should We Accept an Unsupported Claim? If it does not conflict with our observations, our background knowledge or other credible claims. If it comes from a credible, unbiased source. Even Personal Observation Can Be Unreliable If the observing conditions are bad If the observer is distracted or impaired If the instruments used are faulty Other Factors Affecting Personal Observation Individual powers of observation Training and experience Beliefs, hopes, fears, expectations, bias Memory Even so, personal observation is usually the best source of information we have; we should accept it unless we have a specific reason to challenge it. Does the Claim Conflict with Background Knowledge The less conflict, the higher the initial plausibility of the claim. If there is conflict we can rightfully reject the claim even without evidence from personal observation. Remember: Some of your background beliefs are surely wrong but you don’t know which. The broader your background knowledge the better! Assessing the Credibility of a Source: Expertise Education Experience Accomplishments Reputation (especially among other experts) Position All, of course, in fields relevant to the issue. Why Experts Can Be Wrong Expertise can be bought The experts may disagree The subject may be such that none can claim expertise. News Media Print provides broader coverage than electronic Newspapers may feel pressure from advertisers and the local public Headlines are sometimes misleading Size and location of the story may be disproportionate to its importance Opinion sometimes gets blended with facts Slanters These are the various linguistic devices commonly used to attempt to persuade without argument. They rely on the emotive force of words and phrases and/or linguistic manipulations that suggest hidden meanings Words of Caution on Slanters Slanters are only bad when they are used to mislead. Slanters can be combined with perfectly good reasoning (so don’t throw the baby out with the bath.) Sometimes its wise and good to slant. Slanters I: Emotive Force Euphemisms and Dysphemisms: Its all in how you describe it… Persuasive comparisons, definitions and explanations: …or how you compare, define or explain it. Stereotypes: Just read the label. Slanters II: Linguistic Manipulation Innuendo: “I never said he was drunk…” Loaded questions: These have unjustified hidden assumptions (innuendo in interrogative dress) Weaslers: Watering down a claim Downplayers: The verbal brush-off Hyperbole: Extravagant overstatement Proof Surrogates: “Evidence” that isn’t Manipulating the Information I: The News Most stories are given, not dug up; sources must not be offended. Since the news media are private businesses, they mustn’t offend either advertisers or audiences. The result is bias, oversimplification, passivity and an overindulgence in entertainment. We will get the news we want and pay for. Advertising General Question: Does this ad give me a good reason to buy the product?” General Answer: Only if it establishes that I will be better off with the product than without it (or than with the money it will cost). Keep in mind: Wants should be distinct from needs Ads purposefully try to instill desires and fears we previously lacked Three Ways Ads Lacking Reasons Can Persuade By associating the product with pleasurable By associating the product with people we By associating the product with desirable feelings admire or wish to be like situations Unless availability is all you need to know, buying a product based on a reasonless ad is never justified. What About “Promise Ads” that Supply Reasons? Claims in ads often come with no guarantees and are notoriously vague, ambiguous, misleading, exaggerated and wrong. We only get the information the seller wants us to have! Our suspicions about ads in general justifies suspicions about particular ads. So even ads with reasons don’t in themselves justify a purchase. What Pseudoreasoning Is No grounds for accepting a claim are given even though something approximating an argument may be there. Emotional appeals, factual irrelevancies and persuasive devices are used to induce acceptance of a claim. Types of Psedoreasoning Smokescreen/Red Herring Subjectivist Fallacy Common Belief Common Practice Peer Pressure/Bandwagon Wishful Thinking Scare Tactics More Pseudoreasoning Appeal to Pity Apple Polishing Horse Laugh/Ridicule/Sarcasm Appeal to Anger or Indignation Two Wrongs Make a Right Even More Pseudoreasoning Ad Hominem Personal Attack Circumstantial ad Hominem Pseudorefutation Poisoning the Well Genetic Fallacy Burden of Proof Some Oldies but Goodies Straw Man False Dilemma Perfectionist Fallacy Line-Drawing Fallacy Slippery Slope Begging the Question Arguments and Explanations We give an argument to try to settle whether some claim is true. We give an explanation to try to explain why some claim is true. Argument or Explanation? Sometimes the writer doesn’t know They use the same words and phrases (“reason”, “that’s why”, etc.) The word “explanation” and its derivatives can appear in arguments. Explanations can be used in arguments. Sometimes it depends on the context and the interests of those concerned. Explanations and Justifications A justification is an argument in defense of an action. Although justifications often include explanations, explanations can also be neutral regarding approval or disapproval. So not every attempt to explain something is an attempt to justify it; explanations need not imply approval. Kinds of Explanations Physical Behavioral Functional Physical Explanations These seek the physical background causing the event in question. The physical background consists of The general physical conditions (usually unstated) That link of the causal chain leading to the event which, based on our interests and knowledge, we take as the direct or immediate cause of the event. Three Mistakes in Physical Explanations Tracing causal chains back too far Expecting reasons and motives behind all causal chains. Giving physical explanations at the wrong technical level for the situation and/or audience. Behavioral Explanations I These attempt to explain behavior in terms of psychology, political science, sociology, history, economics or “common-sense psychology”. The causal background is historical. Which factors (political, economic, social, psychological) are important depends on our interests and knowledge; there is no single correct explanation of any voluntary behavior. Behavioral Explanations II Recurring patterns of behavior require theoretical explanations. Expect more exceptions to generalizations about behavioral regularities than to generalization about regularities in nature. These explanations can also be traced inappropriately far and pitched at the wrong technical level for the audience. Explanations by reasons and motives look forward, unlike physical explanations. Don’t confuse a reason (argument) for the reason (explanation). Functional Explanations A functional explanation by puts a thing in a wider context and then indicates the role it plays in that context. Actual and intended functions can differ. An item may have more than one function. Since functions usually depend on reasons and motives, functional explanations are often behavioral explanations “in passive voice.” Spotting Weak Explanations I Testability: Beware of rubber “ad hoc” explanations! Noncircularity: Some explanations just describe the phenomena in different words. Relevance: Does the explanation allow us to make predictions? Not Too Vague: “He’s rude because he’s out of sorts.” Reliability: Does it lead to false predictions? Spotting Weak Explanations II Explanatory Power: The more it explains the better (especially if it’s a theory!) Freedom from Unnecessary Assumptions: The fewer the better. Consistency with Well-Established Theory Absence of Alternative Explanations Explanatory Comparisons Analogies aren’t so much true or false as either enlightening or unhelpful. The best comparisons give us the greatest number of close resemblances and the shortest list of important differences. The hearer must be familiar with both terms of the comparison to understand and evaluate it. Argument= Conclusion+Premises A claim can be the conclusion of one argument a premise in another. An argument may have an unstated premise or conclusion. Premises can support the conclusion dependently or independently. Argument Terminology A good argument gives grounds for accepting the conclusion; a better argument gives more grounds. A valid argument is one which, if we assume the premises to be true, the conclusion cannot be false. A sound argument is a valid argument with true premises. A strong argument is one which, if we assume the premises to be true, it is unlikely that the conclusion will be false. Deduction and Induction Deductive arguments are valid or intended by their authors to be valid. Inductive arguments are neither valid nor intended by their authors to be valid. Unstated Premises Is there a plausible claim that will make the argument valid? Is there a plausible claim that will make the argument strong? Be charitable in reconstructing the arguments of others. Evaluating Arguments Do the premises support the conclusion? Are the premises reasonable? Deductive Logic Categorical (class) logic Truth-functional logic Standard Form Categorical Claims A: All __ are __. (quantity: universal, quality: affirmative) E: No __ are __. (quantity: universal, quality: negative) I: Some __ are __. (quantity: particular, quality: affirmative) O: Some __ are not __. (quantity: particular, quality: negative) The terms in the blanks must be nouns or noun phrases (no bare adjectives) The Square of Opposition A and O propositions are contradictories, as are E and I propositions (they never have the same truth-value). Assuming at least one member of the subject class, A and E propositions are contraries (they can’t both be true) and I and O propositions are subcontraries (they can’t both be false). Categorical Operations Conversion: Switch the subject and predicate terms (valid for E and I but not for A and O) Obversion: Change the quality (e.g., affirmative to negative) and replace the predicate term with its complimentary term (e.g., dogs to nondogs) Contraposition: Convert then replace both terms with their complimentary terms. Categorical Syllogisms A two-premise deductive argument in which every claim is a standard form categorical claim (A, E, I, or O). Major term (P): The term that appears as the predicate term of the conclusion. Minor term (S): The term that occurs as the subject term of the conclusion. Middle term (M): The term that appears only in the premises. Testing for Validity with Venn Diagrams Overlapping circles, minor term on left, major term on right, middle term lower middle. Shade out a section to show there is nothing there and put an X in a section to indicate there is something there. Always shade before Xing; diagram A and E premises before I and O premises. The argument is valid if, after diagramming the premises you have already diagramed the conclusion. Distribution Patterns A claim is said to distribute a term if it says something about every member of the class denoted by the term. A: Subject term only distributed. E: Both terms distributed. I: Neither term distributed. O: Predicate term only distributed. The Rules Method of Testing for Validity The number of negative claims in the premises must be the same as the number of negative claims in the conclusion (=1). At least one claim must distribute the middle term. Any term that is distributed in the conclusion must also be distributed in the premises. Inductive Arguments Inductive arguments attempt to establish the likelihood (not certainty) of their conclusions; none are deductively valid. They fall on a scale from very strong to very weak depending on the degree of support provided to the conclusion by the premises. A basic inductive idea is that the more ways some things are alike, the more likely it is that they will be alike in some further way. The Basic Argument Pattern Analogical arguments compare individuals; inductive generalizations compare classes. In both cases the basic argument pattern is: Premise: X has properties a, b, and c. Premise: Y has properties a, b, and c Premise: X has further property p. Conclusion: Y also has further property p Terminology The “property in question” = the property ascribed in the conclusion The “sample” = the group whose members we know have or don’t have the property in question. The “target population” = the individual or group about which we are seeking to know whether or not they have the property in question (this may be a subset of the sample.) Analogical Arguments The premises claim that one or more items have a property, and the conclusion claims that some similar item has that property. Example: The two Yugos I’ve previously driven were underpowered so this one will probably be underpowered too. Factors Governing the Strength of Analogical Arguments I As long as all the members of the sample have the property in question, the larger the sample the stronger the argument. The greater the percentage of the sample that has the property in question the stronger the argument. The greater the number of the similarities (and the smaller the number of dissimilarities) between the target and the sample the stronger the argument. Factors Governing the Strength of Analogical Arguments II With regard to a feature that, to our knowledge, the target may or may not have, the more diverse the sample the stronger the argument. The less narrow the conclusion the stronger the argument. Inductive Generalizations These always have a class as the target. The sample is always drawn from the target population. Basic idea: If a part of a class has the property in question then the class as a whole probably has that property too. The conclusion may refer to all, most, many, or some specified percentage of the target population. Representativeness and Bias A sample is representative of a target population if it has all the relevant features of the target in the same proportions. A generalization not based on a representative sample is untrustworthy. An unrepresentative sample is called a biased sample. We can approximate a representative sample with a random sample, one in which each member of the target has the same chance of being in the sample. Random sampling error can occur even with an unbiased sample. Sample Size, Error Margin, and Confidence Level The error margin is the range within which the conclusion can be expected to fall. The confidence level indicates the percentage of random samples in which the property in question falls within the error margin. As the sample size increases, the error margin will decrease or the confidence level will increase or both. Criteria and Fallacies of Inductive Generalizations The sample must be large enough to be representative of the target population (if not, Fallacy of Hasty Generalization.) The sample must be unbiased with regard to features relevant to the property in question (if not, Fallacy of Biased Generalization.) Basing a conclusion on a few clearly unrepresentative cases is an extreme form of hasty generalization called the Fallacy of Anecdotal Evidence. Untrustworthy Polls Self-selected samples. Person-on-the-street interviews. Telephone surveys. Questionnaires Polls commissioned by advocacy groups. Push-polling. The Law of Large Numbers The larger the number of chance-determined repetitious events considered, the closer the alternatives will approach predictable ratios. This is why we need a minimum sample size even if it is random and unbiased. Using the past performance of an event with a predictable ratio to determine the odds that the next occurrence will be a certain way is the Gambler’s Fallacy. Causation Among Specific Events X is the difference: X caused Y because X is the only relevant difference between the situation where Y occurs and situations in which Y didn’t occur. X is the common thread: X caused Y because X is the only common factor in multiple occurrences of Y. Questions You Should Ask X is the difference: Is X the only relevant difference? X is the common thread: Is X the only relevant common factor? Could Y have resulted from two independent causes? Four Common Types of Weak Causal Arguments Post Hoc, Ergo Propter Hoc: Y (or Y-type events) is caused by X (or X-type event) simply because Y came after X. Ignoring a Possible Common Cause: X and Y may both be caused by a third factor W. Assuming a Common Cause: X and Y may be coincidental, not causally related. Reversing Causality: Y may be the cause of X rather than X being the cause of Y. Causation in Populations: The Search For Causal Factors Controlled Cause-to-Effect Experiments Nonexperimental Cause-to-Effect Studies Nonexperimental Effect-to-Cause Studies Controlled Cause-to-Effect Experiments Randomly divide a random sample of the target group into an experimental group to be exposed to C and a control group treated the same except not exposed to C. Measure the difference (d) in frequency of E between the two groups. If d is sufficiently large, C is a causal factor for E in the population (the target group.) Considerations Is d large enough for the given sample size to be statistically significant? Is the result being analogically extended to a group other than the target population? Is the sample from which the experimental and control groups are taken representative of the population (was it randomly selected?) Are the experimental and control groups selected randomly from this sample? Is the study done by a reputable, unbiased organization? Nonexperimental Cause-toEffect Studies The same as experimental cause-to-effect studies except that the “experimental” group is not exposed to C by the investigators. Important difference: Even if we choose the experimental and control groups randomly from our sample, they may not be alike in all respects relevant to C since exposure to C in the general population may be linked with other factors that make them relevantly different from the control group. We can address this problem by nonrandomly selecting the control group to match the experimental group if factors that might be relevant to E. Nonexperimental Effect-toCause Studies Compare an experimental group already displaying E with a control group none of whom display E in terms of the frequency of a suspected cause C. If the frequency of C in the experimental group significantly exceeds its frequency in the the control up, C may be said to cause E in the target population. Do the subjects in the experimental group differ in some important way from the rest of the population? If so, these factors need to be controlled.