lecture-22-war

advertisement

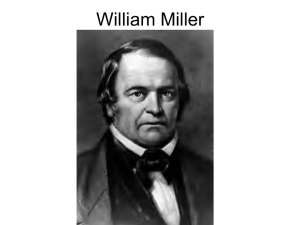

REH417: SDA Church History Lecture 22: Seventh-day Adventists & War The Seventh-day Adventist Church was founded by pacifists. Some early Adventists believed that to even touch a weapon was sinful. While most Seventh-day Adventists favoured the abolitionist cause, the Civil War was not seen as their struggle. In 1862, James White reminded readers of the Review & Herald that involvement in war was incompatible with keeping the fourth & the sixth commandments. He also pointed out that pacifism could be taken to far, and once an individual was drafted, “the government assumes the responsibility of the violation of the law of God, and it would be madness to resist”. White’s editorial caused an outcry from pacifist members like Henry Carver who argued that White’s position was illogical & dangerous: “If the government can assume the responsibility now for the violation of two of [the Ten Commandments], and we go clear, why may not the same government assume the responsibility for the violation of the Sabbath law and we go clear when the edict goes forth that all shall observe the first day of the week?” White did not make the argument again. Ellen White commented on the Civil War: “I was shown that God’s people...cannot engage in this perplexing war, for it is opposed to every principle of their faith. In the army they cannot obey the truth and at the same time obey the requirements of their officers.” Testimonies I, 1863, 361. Seventh-day Adventists usually chose to avoid the draft by paying the standard commutation fee of $300, and churches helped poor members raise this sum. When provision for noncombatant service was passed in February 1864, the church initially made no attempt to gain recognition as noncombatants under the act because they were generally using the commutation fee to avoid service. “Only in July of 1864, when the privilege of buying commutation was restricted to those recognized as conscientious objectors, did the church act to secure such recognition for itself”. (Ron Graybill, “This Perplexing War: Why Adventists avoided military service in the Civil War”. Insight, October 10, 1978, 6.) There was never an agreed moral stance on military service during the Civil War, but later, the church’s policy was clarified as one of noncombatancy—helped by an 1864 law that made special provisions for those against bearing arms. In 1864, the General Conference executive Committee wrote to the governor of Michigan stating: “The denomination of Christians calling themselves Seventh-day Adventists, taking the Bible as their rule of faith and practice, are unanimous in their views that its teachings are contrary to the spirit and practice of war; hence, they have ever been conscientiously opposed to bearing arms. If there is any portion of the Bible which we, as a people, can point to more than any other as our creed, it is the law of the ten commandments, which we regard as the supreme law, and each precept of which we take in its most obvious and literal import.” “The fourth of these commandments requires cessation from labor on the seventh day of the week, the sixth prohibits the taking of life, neither of which, in our view, could be observed while doing military duty. Our practice has uniformly been consistent with these principles. Hence, our people have not felt free to enlist into the service. In none of our denominational publications have we advocated or encouraged the practice of bearing arms, and, when drafted, rather than violate our principles, we have been content to pay, and assist each other in paying, the $300 commutation money.” The governor replied: “I am satisfied that …[Seventh-day Adventists] are entitled to all the immunities secured by law to those who are conscientiously opposed to bearing arms, or engaging in war.” Similar letters were sent to other state governors. On May 23, 1865, the Review & Herald published a General Conference resolution (composed following the civil war) stared that Seventh-day Adventists are “compelled to decline all participation in acts of war and bloodshed as being inconsistent with the duties enjoined upon us by our divine Master toward our enemies and toward all mankind.” In 1886 Ellen White wrote from Europe concerning the Draft: “You inquire in regard to the course which should be pursued to secure the rights of our people to worship according to the dictates of our own conscience. This has been a burden of my soul for some time, whether it would be a denial of our faith and an evidence that our trust was not fully in God. But I call to mind many things God has shown me in the past in regard to things of a similar character, as the draft and other things. I can speak in the fear of God, it is right we should use every power we can to avert the pressure that is being brought to bear upon our people.”—Letter 55, 1886. That same year she wrote concerning compulsory military training in Switzerland: “We have just said farewell to three of our responsible men in the office who were summoned by the government to serve for three weeks of drill. It was a very important stage of our work in the publishing house, but the government calls do not accommodate themselves to our convenience. They demand that young men whom they have accepted as soldiers shall not neglect the exercise and drill essential for soldier service. We were glad to see that these men with their regimentals had tokens of honor for faithfulness in their work. They were trustworthy young men. These did not go from choice, but because the laws of their nation required this. We gave them a word of encouragement to be found true soldiers of the cross of Christ. Our prayers will follow these young men, that the angels of God may go with them and guard them from every temptation.”—Manuscript 33, 1886. During the Spanish-American War of 1898-1899, Seventh-day Adventists continued their pacifist stance. Former Army Sergeant A. T. Jones stated, “Christian love demands that its possessor shall not make war at all….Christians are one sort of people; warriors are another and different sort of people.” Percy Magan criticized American foreign policy in his book The Peril of the Republic, pointing out that American actions in the Philippines were an example of “colonial greed and rapacious lust.” Magan argued that it would be better “for a few missionaries to lose their lives at the hands of heathen savages than for heathen savages to lose their lives at the hands of those calling themselves Christians.” Importantly, Seventh-day Adventist critiques of American foreign policy at this time were eschatologically focussed. America was viewed as the beast of Revelation 13:11-16. “Then I saw another beast which rose out of the earth; it had two horns like a lamb and it spoke like a dragon. It exercises all the authority of the first beast in its presence, and makes the earth and its inhabitants worship the first beast, whose mortal wound was healed. It works great signs, even making fire come down from heaven to earth in the sight of men; and by the signs which it is allowed to work in the presence of the beast, it deceives those who dwell on earth, bidding them make an image for the beast which was wounded by the sword and yet lived; and it was allowed to give breath to the image of the beast so that the image of the beast should even speak, and to cause those who would not worship the image of the beast to be slain.” The outbreak of WWI in 1914 brought new problems—particularly for Seventh-day Adventists in Europe. European church leaders had not attempted to acquaint their governments with the Seventh-day Adventist position on military service—many governments, (including Russia & Germany) made no provision for conscientious objectors. Faced with this reality, on August 14, 1914—almost immediately after the outbreak of war, the president of the East German Conference informed the German War Ministry that “conscripted Seventh-day Adventists would bear arms as combatants and would render service on the Sabbath in defense of their country.” Despite this being in direct opposition to the stance taken by the General Conference, many German Seventh-day Adventists complied with the policy. Many of those who disagreed with the stance of the German church and refused to bear arms were expelled from the church. There were about 4,000 Adventists in Germany and other parts of Europe that were disfellowshipped. Attempts at reconciliation were made at the conclusion of the war, and again in 1920 and 1922. Later the Seventh Day Adventist Reform Movement was organized as a separate church on July 14-20, 1925. In countries outside mainland Europe, Seventh-day Adventists generally had an easier time. In England, Seventh-day Adventists could be assigned to the Noncombatant Corps without difficulty, but faced public ridicule & persecution. Many also faced problems with Sabbath duty and were imprisoned for their stand. Seventh-day Adventist prisoners in Dartmoor Prison, England. Back row from left: Fred Cooper, Albert Pond, Walter Marson, Ron Andrews, Claude Blenco, ?, Rutherford. Front row: Davies, ?, Jack Howard, and Hector Bull. Similar situations existed in Australia, New Zealand, & Canada. In South Africa, the refusal of Seventh-day Adventists to work on Sabbath resulted in prison sentences, but paved the way for a change in policy. (See Francis M. Wilcox, Seventh-day Adventists in Time of War, 318-323.) The US did not enter the war until 1917, however, alert to the possibility of American involvement, the General Conference did advise Seventh-day Adventists to volunteer for a medical role if drafted and the church established several training centres in the US to prepare members for such service. Following America’s declaration of war, the General Conference executive met to decide what the church’s response would be. The committee ratified the Church’s positions of 1864 & 1865—noncombatancy and lodged this statement with the US War Department. While provision was made for conscientious objectors, the rules were not well known & unevenly applied. Because Conscientious Objectors could be assigned to the Medical, Quartermaster, or Engineering Corps, keeping the Sabbath was still a problem for some Seventh-day Adventist soldiers. A request to release Seventh-day Adventist soldiers from Sabbath duty was refused by the army in 1917; however, this decision was reversed less than a year later, and Seventh-day Adventist soldiers were released “from unnecessary Sabbath duties”. In the course of the war however, nearly 200 Seventh-day Adventist soldiers were courtmartialled for failing to obey orders. (Some Seventh-day Adventists draftees had refused to perform any type of military service.) Many were sentenced to long terms of jail—in one case 99 years of hard labour. Most Adventists were released at the end of the war on November 11, 1918, some total pacifists however, were not released until May 1919. Following WWI, the Seventh-day Adventist commitment to not taking life remained, yet church leaders increasingly referred to Adventists as conscientious co-operators: “Refusing to be called conscientious objectors, Seventh-day Adventists desire to be known as conscientious co-operators”. (Review and Herald, 1941. Quoted in Ron Lawson, “Onward Christian Soldiers?: The Issue of Military Service Within International Adventism.” Review of Religious Research, 37:3 (1996), 97-122. The medical training undertaken in America had assisted American Seventh-day Adventist draftees to gain positions in the Army Medical Corps. In 1939, as war broke out in Europe, the church in the US established a formal training program, the Seventh-day Adventist Medical Cadet Corps. Seventh-day Adventist Medical Cadets Training However, the Seventh-day Adventist noncombatancy stand was already being compromised again in Germany, where Adventists praised Hitler and his National Socialists with enthusiasm, and many conscripts bore arms willingly even though they had been accorded the right to opt for orderly or medical duties. Seventh-day Adventists attempted to distance themselves from the Jews by labelling the Sabbath the “Rest day” and Sabbath School as “Bible School”. In so doing they sharply reduced the tension between their church and the state, surviving untouched in spite of the similarity of several of their beliefs and practices to Judaism. Their experience was in marked contrast to that of the Reformed Adventists and the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who suffered greatly, often to death, because of their unswerving commitment to their pacifist positions. Nevertheless, during World War II the General Conference affirmed once more that “throughout their history Seventh-day Adventists have been noncombatants...the noncombatant position taken...is thus based on deep religious conviction”. (Quoted in Ron Lawson, “Onward Christian Soldiers?: The Issue of Military Service Within International Adventism.” Review of Religious Research, 37:3 (1996), 97-122.) Some 12,000 American Adventists served during World War II as non-combatants in medical branches of the services. Church leaders were especially proud of their military heroes such as Desmond Doss, whose bravery earned him a Congressional Medal of Honor. Desmond Doss receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor from President Harry Truman. When the war was over, the immediate incentive for the Medical Cadet Corps was no longer present, and in most places the training was dropped. A few schools continued to offer it, among them Union College. In 1950, the General Conference—in view of the war brewing in Korea—reactivated the Seventh-day Adventist Medical Cadet Corps. Soon Seventh-day Adventist Medical Cadet Corps were founded in many countries around the world: Canada, Brazil, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Dominica, Cuba, Lebanon, Japan, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Philippines. During the Korean War, conscripted American Adventists served in large numbers in medical units. The major innovation during this time was the appointment by the church of military chaplains, who were paid by the armed forces and had military careers. During World War II the General Conference had refused to endorse Adventist clergy for such posts, which had had the effect of keeping them from being appointed. However, it now not only agreed to endorse them, but also to give financial aid to some would-be chaplains in order to help with their ministerial training and to ordain them immediately on graduation, since this was necessary for their appointment as chaplains, rather than having them wait several years, as was the normal procedure with Adventist clergy. South Korean Adventists were also taught during the Korean War that it was the church’s position not to undergo military training with arms—a position that was reinforced by visiting General Conference officials. Consequently, following the American model, the Adventist college there gave basic medical training to those expecting to be drafted, who then asked the authorities to assign them to medical units or other non-combatant positions where they did not have to bear arms. But not all were able to obtain such positions, and the unlucky ones sometimes found themselves with an unsympathetic commander who would not respect their religious restrictions. Two of these were executed at the front line during the war when they refused to bear arms, and about 100 Adventists were sent to prison for as long as 7 years during the 1950s and 1960s for failure to obey orders concerning arms or Sabbath activities; many more were beaten or otherwise mistreated. In 1954, following the Korean War, the General Conference, session voted a statement which both confirmed the traditional noncombatant position and provided for it to be included in the Church Manual as a fundamental belief throughout the world field: “…The breaking out of war among men in no way alters the Christian’s supreme allegiance and responsibility to God or modifies his obligation to practice his beliefs and put God first. This partnership with God through Jesus Christ, who came into this world not to destroy men’s lives but to save them, causes Seventh-day Adventists to take a noncombatant position, following their divine master in not taking human life, but rendering all possible service to save it. In their accepting the obligations of citizenship, as well as its benefits, their loyalty to government requires them to serve the state in any noncombatant capacity...asking only that they may serve in those capacities which do not violate their conscientious convictions”. However, when the next edition of the Church Manual was being readied for printing in 1959, the General Conference Committee voted to omit the above statement from it. Church leaders were becoming more aware of the problems of observing non-combatancy within many portions of the world church, and some felt it would be inhumane to discipline members in such situations—a likely result of including the position among the fundamental beliefs of the church. Nevertheless, in 1963 when the Executive Committee of the General Conference voted a statement which was intended to inform military officers of the Adventist position as American involvement in Vietnam was increasing, it affirmed once more that “Seventh-day Adventists...are noncombatants”. In 1954 US Army Surgeon General contacted the General Conference seeking approval for the Army to ask Adventist draftees to volunteer for a research program designed especially for them which would “contribute significantly to the nation's health and security.” Theodore Flaiz, Secretary of the Medical Department of the General Conference, responded positively: “If any one should recognize a debt of loyalty and service for the many courtesies and considerations received from the Department of Defence, we, as Adventists, are in a position to feel a debt of gratitude for these kind considerations”. This resulted in the formation of “Project Whitecoat,” under which volunteers from among drafted Adventist non-combatant servicemen participated as guinea pigs in biological warfare research for the U.S. Army at Fort Detrick, Maryland. Thanks to the enthusiastic encouragement of the General Conference, 2,200 Adventists participated in the program between 1955 and 1973. Project Whitecoat became especially attractive in the mid-1960s, when the majority of draftees received assignments to Vietnam. Despite the lofty ideals of service proclaimed by some volunteers, the majority of Adventists volunteered for medical research for more pragmatic reason—primarily the desire to stay in the United States. The Seventh-day Adventist Whitecoat volunteers participated in experiments involving the study of biological warfare—both in an offensive and defensive capacity. (See: Krista Thompson Smith, “Adventists and Biological Warfare” Spectrum 25:3 (1996), 35-50.) By the 1950s, American Seventh-day Adventists had become militant patriots. They scorned conscientious objectors, who refused to be involved with the military in any manner and opted for alternative service when drafted. Carlyle B. Haynes, the director of the General Conference National Service Organization, was quoted by Time in 1950: “We despise the term ‘conscientious objector’ and we despise the philosophy back of it... We are not pacifists, and we believe in force for justice’s sake, but a Seventh-day Adventist cannot take a human life”. (Quoted in Ron Lawson, “Onward Christian Soldiers?: The Issue of Military Service Within International Adventism.” Review of Religious Research, 37:3 (1996), 97-122.) In the late 1960s, many Seventh-day Adventist draftees—influenced by the growing antiwar movement—were choosing to register as pacifists rather than as noncombatants. In response, the Annual Council of the General Conference voted in 1969 that such Adventists should be told that the historic teaching of the church was noncombatancy and urged to consider this first. When disagreement and debate on the military issue persisted among American Adventists, the General Conference formed a Study Committee on Military Service in 1971. This large committee received and debated many papers, and remained deeply divided. When Annual Council took up the matter in 1972, it chose to include both the militant patriots and the pacifists, declaring that military service was a matter of individual conscience. Its vehicle in this was the statement on military obligations voted by the General Conference Session in 1954, which it transformed by adding to it a new ending: “This statement is not a rigid position binding church members but gives them guidance, leaving the individual member free to assess the situation for himself”. Adventism in America had backed away from the serious teaching of non-combatancy through Sabbath Schools, youth programming and the church school system. When the U.S. switched to a volunteer army in 1973, recruiters began emphasizing educational and vocational benefits that appealed to lower-SES racial minorities, including many Adventists. These began to volunteer for military service (an act which removed the noncombatant option available to draftees) in unprecedented numbers. The church now directed its main effort into chaplaincy, and by 1992 the Adventist chaplaincy corps had grown to a total of 44. Within the US in the 1990s, “military recruiters come to Adventist school campuses, and school and university bulletin boards display posters advertising the benefits of service in the armed forces”. It is not surprising, then, that “most young Adventist adults are unaware of the strong pacifist thread in the fabric of Adventist history”. In contrast with earlier generations, many young Adventists have enlisted, thereby agreeing to kill America’s enemies if ordered to do so. The office of Adventist Chaplaincy Ministries estimated the total number of military personnel listing Seventh-day Adventist as their “religious preference”—that is, of Adventist background—as 6-8,000 in 1991, and that 2,000 of these participated in the Gulf War. One Adventist Marine, the son of a conference youth leader, was the only survivor when his tank was hit by friendly fire [interviews]. According to Charles Scriven, Adventist attitudes became much more openly jingoistic during the Gulf War: “Not only have [Adventist volunteer soldiers] been to the Persian Gulf and back; they have come home to welcoming applause in Sabbath worship services and patriotic accolades in the church’s publications”. (“Should Christians Bear Arms?”, Adventist Review, June 13, 1991.) A number of countries still have compulsory military service. These include Switzerland, Israel, Singapore, Thailand, Taiwan and South Korea. Seventh-day Adventist face difficulties gaining non-combatant status in many of these countries and may still have difficulties with Sabbath work. U.S. Marine Cpl. Joel D. Klimkewicz and his wife Tomomi In 2001, US Marine Joel Klimkewicz began attending a Bible-study with Chaplain (Lt.) Santiago Rodriguez, a Seventh-day Adventist minister. As a result Klimkewicz asked for and received a generic Christian baptism. Then he began asking the chaplain about his own denomination. Rodriguez directed Klimkewicz to the Jacksonville SDA Church, where he is now a member. In January 2004, soon after re-enlisting, Klimkewicz had discovered arguments in favour of conscientious objection to bearing arms. In April, while his request for reconsideration was pending, he refused an order to take up a weapon during a training exercise. Deciding that Klimkewicz was simply attempting to avoid being posted to Iraq, the military ordered him court-martialled, and on Tuesday, December 14, 2004, he was found guilty of disobeying the order of a superior officer. He was sentenced to seven months imprisonment; reduced in rank to E-1, the lowest possible rank; ordered to forfeit all pay and benefits while incarcerated; and given a bad conduct discharge. General Conference President Jan Paulsen recently pointed out that “The historic position of our church regarding service in the armed forces was clearly expressed some 150 years ago—very early on in our history, against the background of the American Civil War. The consensus, expressed in articles and documents of the time, as well as an 1867 General Conference resolution, was unequivocal. ‘…[T]he bearing of arms, or engaging in war, is a direct violation of the teachings of our Savior and the spirit and letter of the law of God’ (1867, Fifth Annual General Conference Session). This has, in broad terms, been our guiding principle: When you carry arms you imply that you are prepared to use them to take another’s life, and taking the life of one of God’s children, even that of our ‘enemy,’ is inconsistent with what we hold to be sacred and right.” (“Clear Thinking About Military Service”, Adventist World (March 2008), 8.) REFERENCES I: Malcolm Bull & Keith Lockhart, Seeking a Sanctuary 2nd Ed. Indiana University Press, 2007, 273-289. Everett. N. Dick, “The Adventist Medical Cadet Corps As Seen by its Founder.” Adventist Heritage, 1:2, (1974) 18-27. Ron Graybill, “This Perplexing War: Why Adventists avoided military service in the Civil War”. Insight, October 10, 1978, 4-8. Ronald Lawson, “Onward Christian Soldiers?: The Issue of Military Service Within International Adventism.” Review of Religious Research, 37:3 (1996), 97-122. REFERENCES II: Douglas Morgan (Editor), The Peacemaking Remnant, Adventist Peace Fellowship, 2005. Jan Paulsen, “Clear Thinking About Military Service” Adventist World (March 2008), 8-10. Richard W. Schwartz & Floyd Greenleaf, Lightbearers. Rev. Ed. Mountain View: Pacific Press, 2000, 499-517. Krista Thompson Smith, “Adventists and Biological Warfare” Spectrum 25:3 (1996), 35-50. Francis M. Wilcox, Seventh-day Adventists in Time of War, Review and Herald, 1936. “Origin of the Seventh Day Adventist Reform Movement”: http://www.sdarm.org/origin.htm Seventh-day Adventists in the Vietnam War: http://www.adventistreview.org/20021521/story1.html This PowerPoint presentation has been produced by Jeff Crocombe for a class on SDA Church history at Helderberg College in Semester 1, 2008. It should not be used without giving credit to its compiler, nor reproduced in any way without permission. You may contact Jeff Crocombe at: crocombej@hbc.ac.za