¿Quién Soy? Localizando un Lugar en la Historia

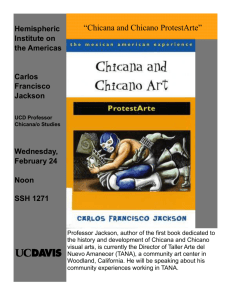

advertisement

¿Quién Soy? Finding My Place in History Personalizing Information Literacy through Faculty-Librarian Collaboration A Poster Session presented by Bárbara A. Miller Chicano Resource Center Librarian, Pollak Library, California State University, Fullerton since 1998, earned a B.A. in Latin American Studies from San Diego State University, and an MLIS from the University of California, Los Angeles. Ms. Miller is the President of the Orange County Chapter of REFORMA, the National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish-Speaking. As a PhD Candidate in Information Studies at UCLA, her dissertation is entitled: “Information Border Crossing: Scholarly Communication and Information Seeking across the U.S.-Mexico Border.” and Nancy Porras Hein Assistant Professor, Chicana & Chicano Studies Department, California State University at Fullerton. She earned a B.A. in Spanish at California State University Fullerton and her Ph.D. from University of California at Riverside. Her dissertation explored the relationship between Chicano parents and public schools. She has published articles on parent participation in schools and family. She presented papers in La Paz, Mexico, Phoenix, Chicago, Albuquerque, Florida and California on the Chicano family and on parent participation and the schools. Dr. Porras Hein has worked extensively with community agencies in Orange County, California. Abstract This poster session describes a long-term, library instruction collaboration between a Chicana/Chicano Studies faculty member and the Chicano Resource Center Librarian at the Pollak Library at California State University Fullerton. Library instruction sessions and a web site have been developed to support a unique family history assignment created by the Faculty member to build student’s selfesteem while allowing them to place their family history into the larger historical context. The problem for the collaborators was to create library sessions and a web site that would provide students with a common set of information literacy skills while offering a specialized set of practical skills needed to successfully complete the genealogical research assignment. We discuss the challenges, solutions, and outcomes associated with personalizing information literacy standards. We conclude with our own self-assessment including suggestions for future improvements. Faculty-Librarian Collaboration In the Fall of 1998, Dr. Porras Hein was among the first Chicana/Chicano Studies professors to take advantage of Ms. Miller’s offer to conduct library instruction sessions for CHIC 305, the Chicano Family. At the time, Ms Miller knew nothing about the practice of genealogical research. She offered library instruction sessions on how to access resources on the historical background. Soon we discovered the world of Internet genealogy. By Spring 1999, we were scheduling two sessions: one to get students started searching the genealogy web portals such as Family Search and another to introduce them to historical research methods. CHIC 305: The Chicano Family Class Syllabus – In Chicana/Chicano Studies 305, students study the Chicano family as an American social institution. The class explores the historical development of “la familia” as well as cross-cultural perspectives on the socio-psychodynamics of the family. The class includes background information on the history of Mexican Americans in the United States and their Mexican heritage. – Student involvement is vital to learning; therefore the class incorporates cooperative learning groups, weekly writing assignments, individual reports, oral presentations, and community involvement. CHIC 305 Spring 2003 Syllabus CHIC-305-02 CHICANO FAMILY-Schedule 11218 Tuesday and Thursday 2:30-3:45 H 521 Dr. Porras Hein (714 278-3733)Email: nporras-hein@fullerton.edu Office Hours: Mondays10-12 a.m.; Tuesdays 1-2 p.m. and Thursdays 8-9 a.m., Humanities 312 G Spring 2003 Course Description: The Chicano family development as an American social institution. Historical and cross-cultural perspectives. The sociopsychodynamics of the Chicano family. A focus on the Chicano family organization and its bearing upon population growth and industrialization. Attention is drawn to the extended family and the nuclear family, their linkages to indigenous family structures. Family typology, roles, cultural values from the perspective of socio-cultural psychology. Data to emphasize variations, migration, urbanization, rural, colonia and barrio life patterns. The goal of the class is to familiarize you with the Chicano Family. Questions pertinent to the objectives to meet this goal include: Why is it important to know the history of the Chicano family in the United States? Why should we have an understanding of the Chicano family economic, social and demographic data? How can knowledge of geographic differences and experiences, with the resulting cultural values, roles and expectations of the Chicano family expand our understanding? How do theoretical frameworks aid us in studying Chicano families? The meeting of the objectives are measured by tests, presentations, class discussions and a paper. Required Texts: Sandra Cisneros, The House on Mango Street Richard Griswold del Castillo, La Familia Robert R. Alvarez, Jr. Familia Grading policy: Family origins paper-group work……………………………100 Family Issues Notebook……………………………………..100 Class participation (attend class, read and bring texts, Blackboard)……………...100 Mid-term Examination……………………………………….…50 Final Examination………………………………………………50 Total……..……400 Syllabus continued Grading Scale: 350-400=A 300-349=B 250-299=C 200-249=D Ten points will be deducted for late papers. Family Issues Notebook: Each student is required to maintain a Family Issues Notebook containing five current newspaper, magazine and journal articles (or four articles and attendance at a Los Amigos meeting in Anaheim with a short one page report) in Education, Health, Politics and Community/Social Concerns. Bring articles as assigned for discussion. Family History Paper Written text must be a minimum of seven pages. Citations for data required. See the family history form for further information. Attendance & Participation Class participation points will be deducted for absences. Insure you sign the attendance sheet. Participation in Blackboard is vital. Read the assigned text. TENTATIVE SCHEDULE Week of Feb. 4th-Introductions-Syllabus-Schedule Overview-review family history form-Read House pp.3-7 Explain Blackboard Week of Feb. 11th-Read – La Familia, Preface and Chapters 1 and 2; Article due, divide into groups, needs assessment, film. Week of Feb. 18th-Read –La Familia , Chapters 3 and 4; and House pp.108-109; Article due Week of Feb. 25th-Read La Familia, Chapter 5 & 6; House pp. 103107, Library Week of March 4th–Read La Familia, Chapters 7 and 8; and House pp.94-100-Article due Week of March 11th-Read Familia, Foreward, Introduction and Chapter 1; film-Family History Preliminary outline due Week of March18th-Read Familia, Chapters 2 and 3; and House pp. 88-93, Article due Week of March 25th-Read Familia, Chapters 4 and 5; Article due Week of April 8th-Read La Familia, Chapter 9; and House pp. 81-87Midterm preparation Week of April 15th-Midterm; Family History Rough draft due; Week of April 22nd–Familia film, Presentations Week of April 29th-Presentations; Family issues notebook due Week of May 6th-Presentations-Family History paper due Week of May 13th-Presentations Week of May 20th-Presentations-Preparation for Final Final Thursday, May 29th-2:30-4:20 p.m. Student Demographics As a course that meets the cultural diversity requirement for general education at CSUF, the Chicano Family draws students from a varied group of departments. – In Spring 2002, twenty-four different majors were represented. Out of 80 students, 15 students majored in Child Adolescent Studies. The second largest group of students were Liberal Studies majors. Other majors included Psychology, Business, Spanish, Sociology, Art, Criminal Justice, Political Science. Less than four percent were Chicana/Chicano Studies majors. – For Fall 2002, the 46 students represented twenty-one different departments. Again, the top two majors remained the same. Majors not represented on the Spring 2002 list of majors include Theatre, Dance, Finance, Electrical Engineering, Accounting and Kinesiology. Slightly over four percent were Chicana/Chicano Studies majors. A cursory look at last names indicates that in Spring 2002, 82.5 percent or 66 students out of 80 appeared to be Chicanos or Latinos. For Fall 2002, of 46 students, 29 or 63 percent appeared to be Chicanos/Latinos. Family History Assignment Students, from all departmental majors and ethnic groups, record their individual family history starting with themselves and going as far back as possible. Following the “Familia History form,” students interview family members to document relevant family history and background. They also must place their families within the historical context. The Family History Assignment is designed to: 1) provide students with a basis for identity creation 2) build student interest and appreciation of Chicana/o culture 3) make students aware of similarities and differences within the structure of all families 4) help students begin to preserve a personal archive of family history, and ultimately 5) assist students in developing important, life-long information literacy skills. History of the Assignment In 1995 when Professor Porras Hein started teaching the Chicano Family course, she had been doing research on her family in Mexico for many years. Inspired by the pioneering anthropological research of Robert A. Alvarez, Jr. chronicling his family’s journey north from Baja California, [i] she decided that students also would benefit from researching their own family history. As Renato Rosaldo notes in his forward to Familia, Alvarez’s study “… also reveals a research process that transforms the researcher. Alvarez becomes conscious of how his familial past has shaped his present.” [ii] [i] Robert R. Alvarez, Jr., Familia: Migration and Adaptation in Baja and Alta California, 1800-1975 (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1987). [ii] Ibid, xiv. Photograph of Dr. Porras Hein’s Family Justification for the Assignment The search for identity and the ability to control the creation of one’s identity is the foundation upon which Chicana/Chicano Studies courses have historically been built.[i] A review of the literature on Chicano identity reveals a plethora of references to the problems Chicanos encounter when faced with negative stereotypes about Mexicans and other Spanish-speaking people.[ii] [iii] [iv] School is where students often experience a rejection of their Mexican roots.[v] [vi] [i] Carlos Muñoz, Jr., Youth, Identity, Power: the Chicano Movement (London: Verso, 1989). [ii] Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic, eds., The Latino Condition (New York: New York University Press, 1998) [iii] Rodolfo F. Acuña, Anything but Mexican: Chicanos in Contemporary Los Angeles (London: Verso, 2000). [iv] F. Arturo Rosales, “Preface,” in Chicano! The History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement, 2nd ed. (Houston: Arte Publico Press, 1997), viii-xix. [v] Peter Iadicola, “Schooling and Social Control: Symbolic Violence and Hispanic Students’ Attitudes toward Their own Ethnic Group,” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 3, no. 4 (December 1981): 361-383. [vi] Roland A. Andrade, “Latino Students: Struggle for Identity,” Latino Studies Journal 1, no. 2 (May 1990): 48-59. Development of the Family History Assignment Originally students just did a family history. Now they … – Use the framework provided by Griswold’s study of Chicano families in the Southwest, to gather information on their ancestors in terms of exogamy, endogamy, immigration, languages, religions, and child rearing – Need to do historical research on their country or countries of origin as well as on the United States during the time period their families emigrated in order to explain the reasons for immigration. – Now (as of Spring 2003) are required to supply a research bibliography of resources consulted to help evaluate student ability to use information critically and assess if students understand the ethical use of information. The class syllabus reflects ongoing assessment by requiring an outline, rough draft and final copy of the paper. Each student also prepares an oral presentation. The Family History assignment requires that students: Select, evaluate, and synthesize information and its sources critically. – Interviews with family members (oral histories) – Learns to search efficiently for information resources in a variety of formats found on websites and databases, in books, articles, archives, attics, garages and basements – Recognize primary resource documentation. Use computer literacy skills to accumulate and record information and to communicate the results. – Includes equipment such as audio and video recorders. – Software like PowerPoint and FrontPage – However Dr. Porras-Hein does not require that these communication technologies be used for the presentation. • Students should have the freedom to decide the best way to present their family story. • While it is important that the decision should be made from a position of understanding and not ignorance of the available technology, being information literate means able to make an informed decision when using information technology is inappropriate. Familia History Form FAMILIA HISTORY FORM The learning objective pertaining to understanding economic, social and demographic information gained through historical accounts of migration and immigration as well as inter-cultural understanding are accomplished through the Family History Papers. The following is a list of information to guide your research. You need to get names and dates of births of parents, siblings, grandparents, great grand parents, etc. Immigration History: When, from where to where, why? Specific information as to how they immigrated. Did one come first, etc.? Background: For example, are they indigenous, Spanish or any other group? Work: What type of work did they do? Did female work at home? Entrepreneurs? Roles: Are there specific roles, like gender roles? Differences between siblings in roles? Patriarchal or matriarchal? Who is the head of the family? How does the family identify itself? Chicanos? Mexicanos? Americans? Etc. Lanuages spoken by members of the family? By generation. Exogamy, Endogamy: Have members of the family married outside of the group? Religions What are the ties to the country of origin? Cultural behavior: child rearing, etc. Trace the familia history to the present. Go back as far as you can go. Gather other information. Interesting information on family member, hobbies (like singing , playing the guitar, etc.). Interview family members. Be sure to videotape or tape the interviews. Use the internet. Barbara Miller will provide information for research on the internet. You will need to locate your family within a historical framework and must provide a minimum of three citations. Need for Library Sessions Students arrive at the library instruction session with a wide variety of information technology skills. Some have used library databases before and some have attended a library instruction session or sessions with other Cal State Fullerton librarians. Most have some experience using a computer and with searching the Internet, but they have trouble transferring their skills to this assignment. They seem to have little idea what they will need to do write a history of their family. The Family as Primary Information Source At the beginning of the class, few students understand importance of their families’ collective memory – To reinforce this during the library session, we encourage students to start searching directly in a genealogy web portal where they need to input ancesters names, important places, dates and events gleaned from interviews with family members. – Many students arrive at the session without sufficient input from their families and experience varying levels of success in the genealogy websites. – Without some idea of family immigration dates, it is impossible for them to use other library resources including online bibliographic and full-text databases to help them situate their family history within its historical context. – Students leave the session with a much better idea of what steps they need to take. Library Session Format The format of the library session for CHIC 305 has evolved from librarian lecture though librarian resource demos to librarian facilitated resource exploration The current open session structure allows students with greater information skills to advance on the assignment, to move about the library, consult reference books, print out materials etc while others can get the help they need. For example, normally the use of cellular phones is not allowed during instruction sessions, but the open session structure allows students to work independently. No one objected when a student, who finally realized that she really needed to know the names of her grandparents to use a web site, called her mother on her cellular phone during the session. Students learn from other students The sessions take place in one of two twenty-workstation computer instruction rooms available at the Pollak Library. Students are encouraged to experiment with genealogy web portals, ask questions and share findings with other class members. For example, a student discovered that only way to limit searches to specific Mexican States was through the international search on the Family Search website. As problems and questions crop up or as new features are uncovered, they are discussed on a central screen that can connect to a librarian-controlled workstation or to any one of the other twenty computers. Website Development In conjunction with the library instruction sessions developed for CHIC 305, Ms. Miller collected genealogical information resources including library databases and genealogy websites and developed a handout. The handout soon grew to be six pages long, making it too awkward for students to use and too difficult for Ms. Miller to update and duplicate every semester. Student wasted time typing in web addresses and following detailed instructions to locate online databases. In the Fall 2001 semester, Ms. Miller transferred these handouts to a website<http://guides.library.fullerton.edu/chic/chic305g.htm>. This allows the students direct access to live links to genealogy web sites and pertinent online databases, e-books and other library resources relevant to the historical context. CHIC 305 Website http://guides.library.fullerton.edu/chic/chic305g.htm Genealogy Portals Other Useful Resources Student Assessment Empirical assessment: – Students must write a paper. – Students present their findings to the class. – Questions about the presentations are included on the class final Class goals: – Stimulate student desire to understand their identity. – Students from all majors have indicated that learning their peers' family histories was a vital part of the class. – Support student efforts to serve their families by preserving their family histories My great grandfather Pedro Perez Migration: Penjamo, Guanajuato Mexico. Fled Mexican Revolution during 1918 to Westminster, CA. Had gold-bought house in Westminster Died of influenza epidemic in 1920. My great grandmother Petra Castillo Perez Work: hacienda & housewife Understood English but preferred Spanish Collaboration Self-Evaluation To facilitate class use of information resources, we intend to incorporate the Family History website into the Dr. Porras-Hein’s Blackboard site for CHIC 305 as well as to explore the possibilities for students to communicate with Ms. Miller via the Blackboard site. We are considering having students maintain information seeking journals that would track where they looked for information, what was useful, what was not, and how they felt about the process. Another area we intend to investigate more thoroughly is the available specialized technologies for generating and manipulating genealogical data. These include audio and visual technologies for conducting oral histories as well as computer programs for creating family trees such as Family Tree Maker. ¿Quién Soy?: Who am I? The greatest satisfaction is to watch students, who may start the assignment complaining that they cannot find anything or questioning what the assignment has to do with their education, be transformed by the power of their own families’ stories. – One student was grateful that he was able to interview his grandfather shortly before he passed away. Now he has a record of his grandfather to share with his newborn son. – Another student, who had never met her father in person and had only spoken to him on the phone, wrote to her father saying she needed information for his side of the family. He sent her pictures of her paternal grandparents, his siblings and his new family. Then he came from Mexico to visit her and brought more family information. She said that the assignment gave them a reason to develop a relationship. – While another student’s mother declared, “At last you are taking a class that will help “la familia.” Personalizing Information Literacy “When people learn technologies they need to see themselves in the technologies. They’ll be able to learn and figure out how it’s related to them. If they can see their own presence it’ll be more important.” “Cuando la gente aprenda usar las tecnologías, se necesita ver a sí mismo en las tecnologías. Pueden aprender y imaginarse como se relaciona consigo. Si se ven a su propia presencia, será mas importante.” - Richard Chabran, Director of the Communities for Virtual Research (CVR) at UC Riverside (Belcher 2001). Spreading the word We believe that it is important to share our collaborative experience. Our first effort in this direction took us out of the country to the Universidad Autonoma de Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, Mexico, where we joined Mexican colleagues working on the development of National Standards for Information Literacy for Mexico. Family History Forms filled out at the Encuentro