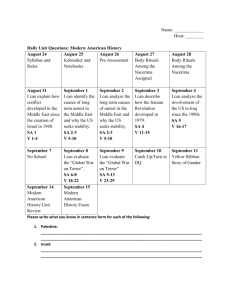

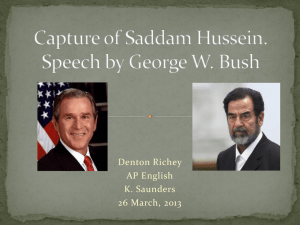

Why did events in the Gulf matter

advertisement