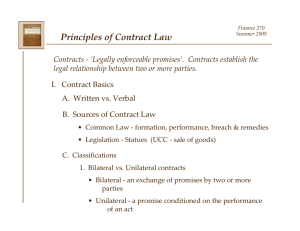

Linzer contracts outline (anonymous)

advertisement