MANY PATHS TO THE SAME SUMMIT – a DRAFT of my manuscript

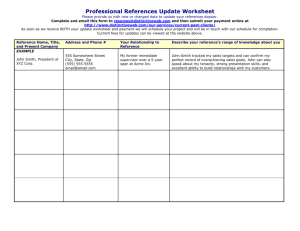

advertisement

What follows are Excerpts from

MANY PATHS TO THE SAME SUMMIT – a DRAFT of my

manuscript, which you can read more of on my website. (Constructive

feedback is very welcome.)

***(fyi, *** means chapters have been skipped for our purposes: you can find missing chapters on the

website)

On the Living Word

Consider how those who live in primal

cultures might spend their days, coming together

around a campfire after work and play to share

the ultimate intrinsic goods of food and drink,

talk and laughter, music and dance. If ancient

and indigenous peoples understand one thing

better than those of us raised in modern cultures,

it is the power and value of the living word as

part of life’s play, perhaps chief among the

intrinsic goods of living.

In the words of esteemed religious

historian Huston Smith, those who still practice this ancient and healing habit are, “Like

bands of blind Homers,” who “gather each evening around their fires” to “revere and

rehearse their heritage endlessly…original language breathing new life into familiar

themes…each supplementing and correcting the accounts of others.” [p.234]

This daily habit of putting their heads together in dialogue is a more joyous

experience than might conceived, at least those of us in the modern world who habitually

retire every evening to the isolation of our homes where we live vicariously through out

televisions. By contrast, ancient and indigenous peoples

were and are more inclined to make the most of this time

and the good fortune that brings them together with family

and friends to enjoy the ongoing discussions that give

meaning to their lives, as well as structure to their

education.

This practice encourages all to be both students and

teachers as they share what they had discovered with all

who might benefit from their learning experience. One can

imagine how ‘the hunt’ or ‘the meal’ or ‘the children’ or

‘the teachings of the ancestors’ could arouse a wonderful

discussions, all contributing their perspective to the whole

ongoing dialogue. And the first advantage of this is that

those who live in oral cultures are never lonely for long, for

the daily lessons they learn in solitude are nightly shared in

the company of their family and friends.

But there is more going on here than what Parmenides calls mere “idle talk.”1

Collective learning comes about as individuals seek answers to intrinsically generated

questions. As Socrates says, “Nothing is an answer if you haven't asked the question.”

And it’s in the dialogue that depth of understanding is achieved, one of several key

insights the ancients called dialectic thinking.

The Hindus, for instance, understood various religions to be ‘many paths to the

same summit,’ which embody the notion that “Truth is one; sages call it by different

names.”2

“At first this may seem

surprising; if there is one

goal, should there not be

one path to it? This might

be the case if we all

started from the same

point, but in actuality

people approach the goal

from different angles, so

multiple

paths

are

needed… The result is a

recognition...that

there

are multiple paths to god,

each calling for a

distinctive

mode

of

approach.”3

And when we inquire of anything from all angles, every new point of view adds

perspective to what could be seen or understood with less (as we’ve said, just as two eyes

give depth to what can be seen with only one). In this way, the whole truth becomes a

meaningful ideal. Weaving perspectives together in this dialectical fashion is precisely

what the mind is good for, and it was for this very purpose that the ancient primal people

gathered each and every evening to celebrate the fortuna of their continued existence, the

way children gather to play.

“What is important for us to understand,” Smith says, “is the impact of this

ongoing, empowering seminar on its participants. Everyone feeds the living reservoir of

knowledge while receiving from it its answering flows of information that stocks and

shapes their lives.”4

And “[T]he overriding advantage of speech over writing is what it does for

memory.” “Everything their ancestors learned with difficulty, from healing herbs to

stirring legends, is now stored in their collective memory, and there only." 5 In other

1

(Plato, Parmenides, p.*)

2

(Smith, p.56)

(Smith, 26)

3

4

5

(Smith, p. 234)

(Smith, p.234)

words, this emphasis that primal peoples put on what Smith calls “the living word”

ensured that, "They remember what is important, and forget the rest."6 And what is lost

without this ongoing process is no small matter – indeed, nothing less than the

understanding of what is important.

“If exclusive orality protects human memory," Smith says, “it also guards…the

capacity to experience the sacred through non-verbal channels," leaving "their eyes free

to notice other sacred conduits (other than books, that is)," such as "virgin nature and

sacred art…"7

By contrast, cultures that look to their sacred texts for revelations also tend to

“marginalizes other windows to the divine.”[p.234] For the fact that might surprise some

of us is that, “during most of human history people have found their sacred texts in song

and dance and paintings and stone more than in writing.”(p.6)

***

On Revelry, Readiness, and Revelation

Primal peoples might remind us to keep in mind that, without

or without words, the revelation of truth was understood to be purely

experiential, an inner phenomena or “rushing progression of

understanding” that can be beyond words altogether, purely

experiential, as is for instance, love. Far from a mere spectacle to be

read or watched from outside-looking-in, philosophy in this sense was,

like music, dance, and poetry, understood as something meant to be

experienced from the inside.

The Bagavad Gita puts it this way:

“what we read are only words. We cannot know the taste of a fruit or of a wine by

reading words about them; we must eat the fruit and drink the wine.”

Like “The seers of the Upanishads [who] did not establish a Church, or found a

definite religion…the seers of the Spirit in all religions agree that communion

with the Highest is not a problem of words but of life.”(p.17)

Again, as Zen masters conceived it, words are pointing tools, but what they point

to in this case is an inner experience that can be ‘known’ only directly, prior to words,

and then only by what the ancients called the ‘initiated’, which is to say, those who are

ready. Unfortunately, we don’t get much initiation in our culture, nor is our learning

process sensitive to student readiness. This process involves a sort of ‘purging’ or

rethinking what we thought we knew, reevaluating what matters. But while words alone

cannot ‘teach’ this kind of understanding to anyone who hasn’t experienced it first hand,

6

7

(Smith, p. 234)

(Smith, p. 234)

they can go a long way toward illuminating the meaning of this experience between

people who have this first hand knowledge, i.e. gnosis.

Also relevant here was the discovery by Pythagoras (582-507 BCE, during a more

folk or primal age of ancient Greece, prior to what we call ‘the golden age’) of the

mathematical ratios of the melodic intervals that gave rise to an understanding of the

rational basis for musical theory. Music was understood by the ancients in its broadest

sense, as any of the arts or sciences that came under the power of the muses (imaginary

maidens who were the daughters of the heavenly Zeus (who represents the creative urge)

and the earthly Mnemosyne (human memory). The muses had the power to inspire

humans to remember their divine origins. In its literal sense, music meant 'remembered

inspiration'.

Music was considered synonymous with order and proportion, and an

understanding of it seemed to be the key to unlocking the secrets of the universe. An

understanding of the order underlying music allowed ancient seers to see the order

underlying so much seeming chaos. “Interestingly, the Greek word nomos, meaning

‘law’, also had the musical meaning of ‘melody’.”(Ehrenreich, p.24)

And while music consists of three things, words, harmony, and rhythm, Plato was

careful to emphasize that harmony and rhythm must follow the words; they pick up

where words leave off. The inarticulate sound and gestures of singing and dancing are

what people resort to when so overcome with feelings that words fail. Hence the reason

that music was primarily considered in relation to literature, drama, and dance (an

Athenian dramatist was responsible for writing the music and training the chorus, as well

as for writing and staging the play).

The Greeks had an elaborate theory that drew out the relationship between various

major or minor modes or scales and the moods and emotions that are associated with

them. In the highest sense of the term music idealized being in tune with the cosmic

forces, having harmony between the physical and the metaphysical, and thus being able

to hear ‘the music of the spheres,’ which was integrally interconnected with immortality.

It's true that this sometimes had sexual overtones for the Greeks -- for discourse is

to the mind what intercourse is to the body, the means by which humans might reach the

heights of human ecstasy, the moment when the human meets the divine, where the

material meets the spiritual, where the visible meets the invisible...the moment when

human beings can, if properly purified

in preparation for the experience, fully

participate in the ‘music of the

spheres’. Call this orgasm, if you like,

but the Greeks would like us to

remember that what we these days

think of as a purely physical

experience,

not

only

has

psychological/spiritual components, but

that there is an orgasmic state possible

in a simple meeting of the minds,

without any physical interaction at all.

Platonic friendship is not a step back

from intimacy, after all, but a step toward it.

True to their conviction that all living things have higher and lower potentials, and

therefore healthier and unhealthier states of being, these primal Greeks aimed to

understand the proper – i.e. healthy – function of music. Following Plato’s conviction

that there is a right and wrong way to use words, so there is a right and wrong way to use

music. It was understood to have a fundamental influence on both personal and social

health and well being. And we are only now beginning to appreciate this medicinal

value of the intrinsic goods of music and dance.

This understanding of the role of music in health gave rise to certain linguistic

images that are still familiar to us today. For instance, when a person is healthy and

happy, they are thought to be like a well-tuned instrument. When they are too tense, they

are said to be high strung, and when they come apart they are said to be unstrung.

And so this state of proper attunement was understood to be the purpose of the

dialectic method, the ultimate stage in the progressive refinement of the means of

attaining ecstasy is ultimately reached, but it’s important to remember that wine, dancing,

laughter, and even sex are all part of the whole of the art. But far from a mere spectacle to

be watched from outside looking in, music, dance, poetry and philosophy and even sexual

intercourse are meant to be experienced from the inside looking out.

This is far better understood in many ancient cultures than it is in ours today,

which perhaps accounts for the sad state of our educational methods. Plato held that the

best education consisted of a balanced curriculum of music for the soul and gymnastics

for the body. Music, in this sense, included everything we might consider to fall under the

umbrella of a liberal education (although, curiously, while there were muses for lyric

poetry, drama, dancing, and song, and even astronomy and history…but there were no

muses for the visual arts, such as architecture, sculpture, and painting…although this

didn’t seem to hold them back, as the Greeks excelled at architecture, sculpture, and

painting).

This is how our ancient betters would recommend we daily celebrate our great

fortune in being alive – by way of these intrinsic goods that are means by which we grow

from our lesser to our better selves, and able to share in this magical experience in this

heavenly place.

As Aeschylus put it in his play, The Bacchae:

For his kingdom, it is there,

In the dancing and the prayer,

In the music and the laughter,

In the vanishing of care.

“Dionysus, whom the Romans called Bacchus – was a democratic god,

accessible to the humble and mighty alike, and had jurisdiction over wine and

vineyard…more spiritual responsibility was to preside over the orgeia…where his

devotes danced themselves into a state of trance…”(p.34)

Some of our cultures of origin have taught us to be suspicious of this kind of

revelry as ‘pagan’, as if it somehow has the devil’s handprint on it. But in the Gospel of

Thomas, Jesus says when asked by his disciples, “When will the kingdom come?" – ‘the

Father's kingdom is spread out upon the earth, but some do not yet see it.’(Gospel of

Thomas)

Indeed, these were the original pagans, and can teach us, if anyone can, that it is

not depravity and decadence that motivates the love of such joyous celebration, but full

appreciation and gratitude for all that is heavenly here on this earth – where mind and

body meet.

Socrates ultimately puts it this way:

“The purpose [of dialectic education] is to bring the two elements [mind

and body] into tune with one another by adjusting the tension of each to

the right pitch. So one who can apply to the soul both kinds of education

blended in perfect proportion will be master of a nobler sort of musical

harmony than was ever made by tuning the strings of the lyre."(Republic,

p. 102)

And this ineffable nature of truth does not diminish

the role of words in the dialectic process, but only

emphasizes that words alone are not enough.

Understanding resides in the soul, prior to words.

Hunnington Cairns, for instance, notes that "the word 'soul,'

with its accretions of meanings during the centuries, is an

unfortunate translation of the Greek word psyche. It is

more properly translated, according to the various contexts,

as Reason, Mind, Intelligence, Life, the vital principle in

things as well as in man; it is the constant that causes

change but itself does not change. “

Here again then, “one explanation of [Plato’s] use

of different words to describe” this inner mind, or what he

called ‘the invisible world,’ “suggests that he hoped to

make us realize that meaning lies not in words but only in

that for which words stand."8

As Aldous Huxley once observed, ‘It is with their muscles that humans most

easily obtain knowledge of the divine.”(*)

In her book, Dancing in the Streets, Barbara Ehrenreich argues that, “Ancient

Dionysian revelers and Christian glossolaliacs believed that their moments of ecstasy

were the gifts of a deity.”(p.94) Ehrenreich discovered in her research “the almost

ubiquitous practice” of dance and what she calls “ecstatic ritual”…which has “an

extraordinary uniformity, in spite of much local variation, in ritual and mythology.”(p.1)

“Ritual dances provide a religious experience that seems more satisfying and convincing

than any other.’”(p.33, Quoted from Dodds, The Greeks and the Irrational, p. 271)

8

(Plato, "Introduction"in Collected Dialogues, p. xx-xxi.)

“[I]ngredients of ecstatic rituals & festivities – music, dancing, eating, drinking,

or indulging in other mind-altering drugs…-- seem to be universal,” she says.(Roger D.

Abraham, in Turner, 1982, pp.167-168 ] Indeed, “[A]nthropologist Erika Bourguiguon

found that 92 percent of small-scale societies encouraged some sort of religious

trance….most cases through ecstatic ritual.”(Goodman, p.36)

Apparently, most humans throughout time have spoken “the language of extreme

experience…with the idea of over extending the self…stretching life to the

fullest…”(Roger D. Abraham, in Turner, 1982, pp.167-168)

Clearly, dancing “did not seem like a waste of energy to prehistoric

peoples.”(p.22) “At one recently discovered site in England, drawings on the ceiling of a

cave show ‘conga lines’ of female dancers, along with drawings of animals like bison and

ibex, which are known to have become extinct in England 10,000 years ago” (Pickrell,

National Geographic News, August 18, 2004) “So well before people had a written

language, and possibly before they took up a settled life style, they danced and

understood dancing as an activity important enough to record on stone.”(p.21)

But “[D]ance cannot work to bind people unless…it is intrinsically

pleasurable…whatever the ritual dancers of prehistoric times thought they were doing-…-- they were also doing something they liked to do and liked enough to invest

considerable energy in.”(p.25) As all intrinsic evidence suggests, “dancing is

contagious.”(p.25) Which is perhaps why dance is “the hallmark of so many ancient and

indigenous religions.”(p.87)

“Dance, whether of the ecstatic or more stately variety, was [also] a

central and defining activity of the ancient Greek community…dances at

regularly scheduled festivities or what appear to have been spontaneous

outbreaks, dances for victory, for the gods, or for the sheer fun of it.”

(p.32, Lawler, pp. 238-39)

“The religion of the ancient Greeks was a

‘danced religion’, much like those of the

‘savages’ European travelers were later to

discover around the world,” to which they often

reacted with great revulsion. But “the

ambivalence and hostility found in ancient written

records may tell us more about the conditions

under which writing was invented than about any

long-standing prior conflict over ecstatic rituals

themselves. Writing arises with ‘civilization,’ in

particular, with the emergence of social

stratification and the rise of elites.”(p.44)

“Ecstatic rituals…build group cohesion, but when

they build it among subordinates – peasants,

slaves, women, colonized people – the elite calls

its troops.”(p.251)

out

As it turns out, “The aspect of ‘civilization’ that is most hostile to festivity is not

capitalism or industrialism – both of which are fairly recent innovations – but social

hierarchy, which is far more ancient. When one class, or ethnic group or gender, rules

over a population of subordinates, it comes to fear the empowering rituals of the

subordinates as a threat to civil order.”(p.251) “Hierarchy, by its nature, establishes

boundaries between people – who can go where, who can approach whom, who is

welcome, and who is not. Festivity breaks these boundaries down.”(p.252) “The rise of

social hierarchy, anthropologists agree, goes hand in hand with the rise of militarism and

war, which are in their own way also usually hostile to the danced rituals of the archaic

past.”(p.44)

By contrast, “Dionysus was a lover of peace…and like Jesus, he upheld the poor

and rejected the prevailing social hierarchy,”(p.39-60) Whether “Jesus was, or was

portrayed by his followers as, a continuation of the quintessentially pagan Dionysus,”

there is much evidence that the two had much in common. “Strikingly, both are

associated with wine; Dionysus first brought it to humankind; Jesus could make it out of

water.”(p.59)

“Women, above all, responded to Dionysus’ call”… and Like Jesus, “Dionysus

had a special appeal to the women of the Greek city-state, who were ordinarily excluded

from much of public life.”(p.34) Both represented “A feminine, or androgynous, spirit of

playfulness versus the cold principle of patriarchal authority.”(p.55) So it is no surprise

that and why later fathers of the Christian Church could not do enough to disassociate

their doctrine with all things ‘pagan’ – which means only ‘Greek and all things before’.

“The most notorious feminine form of Dionysian worship, the oreibaia, or winter

dance,” which “looks to modern eyes like a crude pantomime of feminist revolt.”(p.35)

But as Ehrenreich emphasized, “Whether the women’s dances were really lewd or only

appeared so” through Christian eyes that wilfully misread them is a matter of some doubt.

“The most famous literary account of maenadism, Euripides’ play, The Bacchae, clearly

refutes the notion that sex or even drunkenness was involved.”(p.37) “Given the

persistent tendency to confuse communal ecstasy and sexual abandon,”(p.71) and the

failure to recognize the “Greek understanding that collective ecstasy is not fundamentally

sexual in nature,”(p.39) this practice is better understood as an attempt to “achieve a state

of mind the Greeks called euthousiansmos – literally, having the god within

oneself.”(p.35)

Early Christians, taking

their cue from the Delphic

Oracle, called this “inexpressible

love” glossolalia, much the same

phenomena that is later called

‘speaking in tongues.’(p.70) As

this ‘gift’ carried some prestige

and is also all to easily faked

(p.69), it was rebuked by Paul as

excessively

enthusiastic,

impossible to verify, and

ultimately unintelligible.(p.6869)

“If we know one thing about Paul, it is that he was greatly concerned about

making Christianity respectable to the Romans, and hence as little like the other ‘oriental’

religions – with their disorderly dancing women – as possible.”(p.66) “Clearly, concern

over the integrity of Roman manhood was chief among” the worries of orthodox church

fathers who would later proclaim as the excuse for forcibly suppressing them (following

the Roman historian, Livy), that “women in general ‘are the source of this evil thing,’

meaning the entire Bacchic ‘conspiracy’.”(p.54) Which inverts the comfortable hierarchy

of power that serves the powers that be.(p.103)

“[T]he Church was determined to maintain its monopoly over human

access to the divine” and would go to great lengths to see to it that

“ordinary people [never] get the idea that they could approach the deity on

their own (as did, for example, the ancient worshipers of

Dionysus).”(p.84)

So dance was treated by the powers that be as a “form of heresy: Nothing is more

threatening to a hierarchical religion than the possibility of ordinary lay peoples finding

their own way into the presence of the gods.”(p.86) For “Dionysus…did not ask his

followers for their belief or faith; he called on them to apprehend him directly.”(p.256)

As we will see, it wasn’t long before the “Church began to crack down on

religious dancing, especially by women.”(p.73) But we moderns can hardly conceive that

“These occasions were, in an important sense, what men and women lived for.”(p.92,

E.P. Thompson, Customs in Common, p.51) Nor that “Festivity – like bread or freedom –

can be a social good worth fighting for.”(p.94) Something “we need much more of on

this crowded planet, to

acknowledge the miracle of

our simultaneous existence

with

some

sort

of

celebration.”(p.261)

Organized religions

(p.77-117) and organized

sports (p.225-245) have tried

to fill this gap, to little avail.

Indeed, as Emile Backtin’s

great

insight

indicates,

"carnival

is

something

people create and generate

for

themselves.”(p.95)

Hence, the reason why

spontaneous rock concerts

and festivals serve this need

somewhat better than those

that are organized. (p.207224) “This is how danced

rituals and festivities served

to bind prehistoric human groups, and this is what still beckons us today.”(p.251)

Emile Durkheim claims it is the ecstasy of dance that “defines the sacred and sets

it apart from daily life…”(p.39, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, p.250)

“…something we might call meaning or transcendent insight. In ancient Dionysian forms

of worship the moment of maximum ‘madness’ and revelry was also the sacred climax of

the rite, at which the individual achieved communion with the divinity and a glimpse of

personal immortality.”(p.95)

Ehrenreich asks, “why have we forgotten them, if indeed we have?”(p.19) “We

can live without it, as most of us do,” Ehrenreich says, “but only at the risk of

succumbing to the solitare nightmare of depression.”(p.260)

In their misunderstanding of the practice, “The early Christian patriarchs may not

have realized that, in attempting to suppress ecstatic practices, they were throwing out

much of Jesus too.”(p.76)

“The ecstatic rituals of non-Western peoples often have healing, as well as

religious, functions…and one of the conditions they appear to heal seems to be

what we know as depression.”(p.150) Jesus is said by many to be “a cure for

depression, alienation, loneliness, and even mundane, all-too-common addictions

to alcohol and drugs.”(p.256)

“[D]epression is now the fifth leading cause of death and disability in the

world.”(p.131) It is “characterized by an inability to experience pleasure – can kill by

increasing a person’s vulnerability to serious somatic illnesses such as cancer and heart

disease.”(p.132) It is a “disease that strikes the poor more often than the rich, and women

more commonly than men.”(p.132)

And yet the “demonization of Dionysus began by Christians centuries

ago…thereby [rejecting] one of the most ancient sources of help – the mind-preserving,

lifesaving techniques of ecstasy.”(p.153) As it turns out, Ehrenreich argues, what many

ages call “madness” may also be a cure for madness, and depression.(p.41)

“[I]f all they found in their religious ritual was a moment of transcendent joy –

well, let us give them credit for finding it. To extract pleasure from lives of

grinding hardship and oppression is a considerable accomplishment; to achieve

ecstasy is a kind of triumph.”(p.178) “A psychic benefit is no small thing.”(p.178)

Whereas many of us have learned to pray for what we want, primal and

indigenous peoples would pray to express appreciation for all they have. For all the

struggles and suffering that the body endures, it can also taste the most delicious fruits,

smell that scents of flowers, hear the sounds of music, touch and be touched by a lover,

and see the beauty of both the physical and the metaphysical world. If life is an

opportunity for humans to touch the divine, it is ironically through our mortal bodies that

we experience and best appreciate this heaven. Indeed, as Brad Pitt’s Achilles suggests

in the film Troy, the gods have reason to envy us.

Anyone who goes through this purification process by which it is achieved may

understand it, but it cannot be put into words for someone who has not earned the

experience. As Zen masters would say, ‘A finger is used to point at the moon, but let’s

not confuse the finger with the moon.” Words are pointing tools, but what they point at

when they talk of truth is an inner experience that cannot be seen by the uninitiated.

Which is why the Eleusian mysteries (the folk religion that most 5th century BC

Athenians still participated in) were practiced continuously for over two thousand years

without anyone ever revealing the secret (although some playwrights hinted at it in ways

that almost got them prosecuted). Part of the taboo was a sort of honor code, to be sure –

(similar to that against giving away the ending of a movie to someone who has not yet

seen it). But it was also a recognition on the part of the initiated that the experience

simply cannot be put into words; if it could, there would be no need for the purification.

Far from an ‘immoral’ activity, the ancients pushed the limits of this ecstasy with

a long an grueling process of moral purification prior to celebration, including talk, food,

wine, music and dancing as a means of spiritual uplift, which became refined in time into

poetry, drama, and philosophy. It was a multifaceted process that might include fasting

and resolution of interpersonal conflict as the means by which the ultimate ecstasy of

one’s highest potentials might be reached.

***

On Hinduism

Intelligently

and

Seeking

Pleasure

After having been taught to think of all

things pagan as more demonic than devine,

many of us experience with surprise coming to

see the deep moral code that guided these

ancients, who knew full well the wisdom to

“seek pleasure…but only intelligently,” that is

according to the inexorable “law of karma

[that] renders the cosmos just,” and in the end,

good.

The concept of karma has a history that goes back long before any of these

traditions became identifiable in and of itself, but it comes to us most explicitly by way of

the evolution of eastern thought.

Consider the following passage offered us in the first pages of the Hindu Upanishads:

“The good is one thing; the pleasant is another. These two, differing in

their ends, both prompt to action. Both the good and the pleasant present

themselves to men. The wise, having examined both, distinguish the one

from the other. The wise prefer the good to the pleasant; the foolish,

driven by [shallower] desires, prefer the pleasant to the good. Blessed are

they that choose the good; they that choose the pleasant miss the

goal.”(p.3)

Ancient Vedic Hindus help their young understand this distinction by way of a

story about a magic wishing tree, called Kalpatura, which has branches that reach into

every human heart. Kalpatura grants all wishes, together with all consequences of those

wishes. And naturally, like children, most people will at first shower the magic tree with

requests. But, as children learn, so do we all, that with too much candy comes

indigestion. Likewise, all desires come with an inexorable price. Not all pleasures are bad

pleasures, but those that bring bad consequences might not be worth their cost. And so it

is that, with learning, a wise person will come to choose their wants with careful

discretion. 9

Kalpatura,

the magic wishing tree…

Ancient Vedic Indians would tell their

young a story about a magic wishing

tree, called Kalpatura, to illustrate the

nature of desire and pleasure, and the

dangers of unbridled want. Kalpatura

has branches that reach into every

human heart, and grants all wishes,

together with all consequences of those

wishes. Naturally, like children, most

people will at first shower the magic

tree with requests. But, as children

learn, so do we all, that with too much

candy comes indigestion. Likewise, all

desires come with an inexorable price.

Not all pleasures are bad pleasures, but

those that bring bad consequences

might not be worth their cost. And so it

is that, with learning, a wise person,

who wants true and good pleasures,

will come to choose their wants with

careful discretion. (Huston Smith, p. 50)

There is nothing wrong with

seeking pleasure…as long as one

does so intelligently! (that is,

according to the moral laws of the

universe).

As Huston Smith shows, “Hindu literature is studded with metaphors that are

designed to awaken us to the realms of gold that are hidden in the depths of our being.

We are like kings who, falling victim to amnesia, wander our kingdoms in tatters… We

are like a lover who, in his dream, searches the wide world in despair for his beloved,

oblivious of the fact that she is lying at his side” all along.10

As we will see, the ancient Hindus - like empathic parents - understood that we

are always growing, always learning, hopefully for better rather than worse. We are born

with attraction to pleasure and aversion from pain for good reason, because our survival

depends on choosing wisely between them. But people being different from one another,

at different stages in their learning process, and even different from themselves at

different stages in their lives, also differ in their desires according to what they have

learned about what is better and worse for them.

9

(Smith n.d., 50)

(Smith n.d., 25)

10

They understood and taught that want of various kinds of pleasure is perfectly

understandable and even good for us, as long as we want what’s actually good for us, and

are learning from the experience. So desire is not to be condemned across the board. But

the human ego can become confused about what is good, and the more it wants of what

isn’t in its better interests, the less satisfaction it actually achieves. And the reverse is also

true: as Epicurus put it: the less we desire, the easier it is to experience satisfaction. And

so a wise person will indeed seek pleasure, but will do so intelligently, so to learn in the

process the difference between true pleasure and imposters.

Others insights can help guide us, but it is ultimately from our own experience

that we come to see what’s worth trading for what. So enjoy those true and intrinsic

goods that are widely available in human life…and learn their difference from seeming

goods that ultimately bring more pain than pleasure. Good pleasures will have good

consequences, whereas bad pleasures will make us regret them, in one way or another.

Even if gods and men never know, as Socrates says, we’ll know…b/c one cannot run

away from one’s own memory, wherein one’s self-knowledge resides. (This would be

argument enough against the death penalty to convince me, btw. People who have created

such memories for themselves ought to have to live in the hell on earth they’ve created

inside their own being.)

Aristotle too argues this controversial

point, concluding that, just as a ‘bad’ person’s

suffering sometimes cannot be seen by others, a

good person’s pleasure will be theirs alone to

enjoy, an experience unavailable to a person of

lesser character. Though outward signs may

abound, “The pleasure of a just man can never be

felt by one who is not just.”11

We might rightly wonder who is to say

what true happiness actually is? Who has a right

to declare one kind of pleasure qualitatively better

than pleasure in another sense? Aristotle would

answer – it is the person who has experienced

both. That is the point of view from which the

difference can best be seen, known only by the

empathy in memory in those who’ve learned

better.

As you can see, the ancients held a view of

human nature that is more generous than the

typical western view – one that understands that all are always learning. They understood

that we are born fundamentally good, though it may be difficult to maintain, and

ultimately buried deep within us, beneath “an almost impenetrable mass of distractions,

delusions, and self-serving instincts…[of] our surface selves.”(Smith, 22) But just as “a

chimney can be covered with dust, dirt, and mud to the point where no light pierces it at

all,” so “the human project is to clean one’s ‘chimney’ to allow the light within to

11

(Nicomachean Ethics)

radiate” outward.(Smith, 22) For indeed, inside the human being “is a reservoir of being

that never dies, is never exhausted, and is unrestricted in consciousness and bliss. This

infinite center in every life, this hidden self or Atman, is no less than Brahman, the

Godhead.”(Smith, 22) And the integration of Atman-Brahman – the human self,”(Smith,

22) is the very purpose of human life. Happiness itself depends on this earned potential.

On Yoga

To understand this better, consider the concept of yoga, which grows from this

conception of diverse paths converging on a common goal -- actualizing the human

potential for strength, wisdom, and joy. Which is to say, “the infinite ocean of life’s

creative power,” which “we carry…within us…but it is deeply hidden.”(Smith, 26)

Of

all

the

religions,

Hinduism tends to stand alone is

recognizing “different spiritual

personality types,” Smith says, each

of which more naturally prefers one

of the “multiple paths to God, each

calling for its distinctive mode of

approach.” But “Hinduism is

exceptional in the attention it has

given the matter; it identifies the

principle types and delineates the

programs that are suited to each.” 12

The word yoga comes from

the same root as the English word yoke, connoting integration or union with one’s divine

creative power. The purpose of yoga is to actualize the ultimate human potential, to

“direct personal experience of ‘the Beyond within.’ Its method is willed introversion, its

intent, to drive the psychic energy of the self to its deepest part, “the infinite ocean of

life’s creative power,” (p.26) and ultimately to become “in full what one always was at

heart.”(p.27)

And “the spiritual trails that Hindus have blazed toward this goal are four.”(p.26)

They are:

jnana yoga (emphasizing knowledge, reflection, the shortest and steepest

path)

bhakti yoga (emphasizing emotion, love)

karma yoga (emphasizing work, energy), and

raja yoga (emphasizing self-experimentation)

“Different starting points here really refers to different types of people.”(Smith,

26) Still, “No individual is solely reflective, emotional, active or experimental, and

different life situations call for different resources to be brought into play. [Still] most

people will find that they make better time on one road than the others, so will keep close

12

(Smith, .26)

to it: but Hinduism encourages people to test all four and combine them in the ways they

find most productive.”(p.38) So just as “all hands of cards include all four suits. But one

normally leads with one’s strongest suit.”(p.26)

However, in keeping with the founding principle of karma, the ancients

understood that there are “moral preliminaries common to all four yogas, for unless one’s

personal life is in reasonable order and one’s relationships harmonious, there can be no

hope of deeper self-knowledge; the surface waters will be too choppy.”(p.34) But as the

Taoists will say, “Muddy water let stand will clear.”(Tao Te Ching)

“The first step of every yoga, therefore,

involves the dismantling of bad habits and the

acquisition of good ones.”(p.26) For “to discern

the self’s deep-lying divinity, the scum on its

surface must be removed. Selfishness muddies

the water, ill-will skews objectivity.”(p.26)

But “To the mind that is still, the whole

world surrenders.”(Smith, p.131) And it is this

ultimate concentration that is the goal of all

paths. And meditation is often used to turn this

from a chance occurrence to a controlled

skill.(Smith, 37) For “When all the senses are stilled, when the mind is at rest, when the

intellect wavers not – that, say the wise, is the highest state.”(Katha Upanishad, Smith,

38)

So what is this highest state or summit toward which all paths lead? Nothing more

or less than a genuine understanding of what is truly good for us, as distinct from what

we merely think we want. This is the lesson our young need us to pass on for their sake,

so one we would do well to consider more deeply than we do.

It is by way of such metaphors that the ancient Hindu sages understood the nature

and danger of misunderstanding human want in a way long lost in our modern world.

And it could take us a long way toward helping one another and our young learn the

difference in what we merely want, and what we truly need, and indeed, the difference in

what we think is good, and is actually good for us.

Indeed, much of our suffering, as Buddha would later teach, results from wanting

what’s not good for us, and both getting and not getting what we want, as karma would

have it.

On Karma

The word karma literally means work, action, or deed, and is “the mechanism by

which spirit works.”(Radhakrishnan) As revealed in the Rig Veda, the earliest of the four

Vedas, in about 1400 B.C.C.

“The law of karma is the counterpart in the moral world of the physical…law of

the conservation of energy.” 13 Or, as we put this idea in the biblical west, “’As a man

sows, so shall he reap.’”(Smith, 49) And just as we understand in the west that “for every

13

(Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, Indian Philosophy, Chapter 4: The Philosophy of the Upanisads, Section 19.

Karma)

action there is an equal and opposite reaction,” so the law of karma “brooks no

exceptions.”(Smith, 49) There is “nothing uncertain or capricious” about it – “we reap

what we sow. The good seed brings a harvest of good, the evil of evil.”(Radhakrishnan)

In other words, in as much as “Karma is a blind unconscious principle governing

the whole universe.” it requires no judge to administer it, no higher principle to direct it.

It is thus not subject to the control or the exception, even of God.(Radhakrishnan)

“Anthropomorphically we can say a divine power controls the process,”(Radhakrishnan)

but one cannot count on one’s personal relationship with said God to get one off the hook

when it comes time to pay ones dues. Indeed, we should not expect a good God to play

favorites anyway, any more than we would expect a good parent to make exceptions for a

favorite child. What would that teach them, after all, except to try to cheat by kissing up

to the rule maker? We might see in this latter-day belief the root of injustice, whereby

humans begin trying to ‘cheat’ if you will.

Indeed, karma “renders impossible any arbitrary interference with moral

evolution.”(Radhakrishana) Rather, karma keeps the spiritual universe absolutely just,

and encourages personal responsibility for the direct and intrinsic connection between

one’s goodness and its ultimate rewards, rather than encouraging an ulterior and extrinsic

motive for creating the mere appearance of goodness in the eyes of a god, a church, or the

world. And while karma is not incompatible with the idea of God, it holds that even God

– indeed, especially God – is bound by the moral law.

“The divine expresses itself in law, but law is not God. The Greek fate, the Stoic

reason, and the Chinese Tao, are different names for the primary necessity of

law.”(Radhakrishnan) And because the law of karma is always fair, it will not advantage

some and disadvantage others, as a god who plays favorites might. All can learn to be

good, though not all will in a single lifetime.

And for this reason, Rhadikrishnan tells us, any “attempt to overleap the law of

karma is as futile as the attempt to leap over one’s

shadow. It is the psychological principle that our life

carries within it a record that time cannot blur or death

erase.”(Radhakrishnan) Which implies, importantly,

that a proper take on karma must understand that, just

as “Every deed must produce its natural effect in the

world,” so “it leaves an impression on or forms a

tendency in the mind of man.” And just as “all deeds

have their fruits in the world,” so to they have their

“effects on the mind.” For this reason, so-called good

and bad karma cannot be measured in extrinsic

fortunes. “Every little action has its effect on

character…[and] conscious actions tend to become

unconscious habits.”(Radhakrishnan)

But by this cause and effect necessity, karma

does not eliminate freedom, for while the conditions

from which we act have been dealt us by our past

actions, the will remains free to choose how we will act

and react to our present situation. “Whatever happens to us in this life…is the result of

our past doings. Yet the future is in our power, and we can work with hope and

confidence” that virtue will bring good.

And so, as the practice of yoga illuminates, “By self-discipline we can strengthen

the good impulses and weaken the bad ones.” And in this way, “our karma limits our

freedom, but it does not eliminate it.” For “freedom and karma are [but] two aspects of

the same reality.”(Radhakrishnan)

Still while “every decision must have its inexorable consequences…the decisions

themselves are freely arrived at.” And the “course that a soul follows is charted by its

wants and deeds at each stage of its journey.”(Smith, 49) To return to our card playing

metaphor, Smith says, “The hand that a card player picks up he dealt in a former life; but

he is free to play it as he chooses.”(Radhakrishnan)

And so, while many may consider their fortunes to be gifts from a divine giver,

these ancient sages saw such blessings as the just deserts of a potentially divine chooser.

For “there is a soul within him which is the master,” and the “more he realizes his true

divine nature, the more free is he.”(Rhadakrishnan)

The ancient Hindus teach us then to consider our progress carefully so to advance

toward perfection or spiritual excellence (that is, toward life, wisdom, and happiness)

rather than away from it (toward death, ignorance, and misery). A soul just beginning its

psychological journey will naturally follow a path of desire that will begin with want of

immediate pleasures. And indeed, to the hedonist, Hinduism would say, go for it – just

use good sense and follow the moral law of nature, for our pleasures ought not to cause

others or ourselves pain. Ultimately, by way of this learning process, we come to see that

it stands to reason that, “Small immediate goals must be sacrificed for long range gains,

and impulses that would injure others must be curbed to avoid antagonisms and remorse.

Only the stupid will lie, steal, cheat, or succumb to addictions. But as long as the basic

rules of morality are observed, you are free to seek all the pleasure you want.”(Smith, 18)

Even though physical pleasure is at the bottom rung of other higher pleasures one

might choose, it is nonetheless one of the four legitimate life goals that Hinduism

recognizes. And therefore, there is nothing shameful in its pursuit. “Quite the contrary;

the thought of children without toys is sad. Even sadder, though, is the prospect of adults

who remain fixated at their level.”(Smith, 20) For just as a child learns to enjoy ever

more challenging toys over time, so each of us who learns will discover the delights of

the senses,” however, those “that seemed exhilarating when the experience was new may

very well come to seem unfulfilling over time.(Smith, 49) And when they do, the wise

spirit will choose to advance upward through higher stages of pleasure toward

understanding of ever higher goods.

Mind you, it is because psychological maturity may not correspond with

chronological age that the ancients were compelled to consider the possibility of past

lives. People are different, and the Hindus understand this, in part, as the result of past

learning, or its lack. Hence the reason we see wise children and old fools. Still, while not

everyone decides to advance in this life, everyone can who choose to learn.

And so next along the path is desire are accomplishment and worldly success,

usually taking the form of wealth, fame, and glory. But “Wealth, fame, and power are

exclusive, hence competitive, hence precarious….as other people want them too, who

knows when fortune will change hands?”(Smith, 18) “Unlike mental and spiritual

treasures,” these zero-sum (extrinsic) goods can easily be lost. What’s more, even when

they can be maintained in abundance, these too will ultimately come to seem trivial and

unfulfilling. Smith observes that, “To try to extinguish greed with money is like trying to

quench fire by pouring butter over it.”(Smith, 19)

All the same, many people are content with their material lot, sometimes for

entire lives, though they don’t know what they are missing, and are often deeply aware

that they are indeed missing something. “It is people who place these things first in their

lives who cannot be satisfied, and for a discernable reason.”(Smith, 19) Sadly, it is often

these who will pursue this futile process indefinitely, somehow expecting different

results. But just as money is not an end in itself, but a means to other ends, so all

excessive wants are ultimately unsatisfying, because “you can never get enough of what

you don’t really want” to begin with.(Smith, 19)

What we really want are the ends to which these pleasures are only means, such

as security, comfort, and freedom. But for those who do not recognize this, the process

can be unending. Indeed, “The parable of the driver who kept his donkey plodding by

attaching a carrot to its harness comes from India.”(Smith, 19)

So the attentive spirit will come to see that all wants are mere means to other

ends, all desires are paths to higher goals. These wants are, Smith explains, like apertures

that let in a little light at a time, and it is by way of these windows that we come to see

what is beyond our seeming wants, toward the higher and deeper goods that are what we

actually and ultimately want. Or, if we resist what is shown us by way of our learning

experience, our wants can also limit and

blur our awareness, getting in the way of

our potential vision of those more

rewarding of life’s purposes.

In fact, it turns out, “Pleasure,

success, and duty are not what we really

want, the Hindus say; what we really

want is to be, to know, and to be happy.”

Indeed, what we really want is liberation

(moksha) from want altogether. We want

“liberation from

everything that

distances us from infinite joy, infinite

awareness, and infinite being.”(Smith,

22) In fact, what we really want is those things in infinite degree.”(Smith, 22)

So it is that by learning from ones experience of pleasure and worldly goods, a

wise soul will advance on up the ladder, beyond the self-centered path of desire and

toward an other-centered path that leads beyond those less fulfilling goods, which can be

traps by which a spirit becomes tethered to dissatisfaction. But again, not everyone will

choose the path of maturity in this life, and some of them, not knowing what they’re

missing, “will die with a sense of having had a good life.”(Smith, 21)

But for those who do advance in their spiritual understanding, the will to get will

ultimately turn to the will to give, and the will to win turns into the will to serve.(Smith,

21) On this higher path of renunciation, the psychologically maturing spirit will come to

seek the higher goods of respect and self-respect that come with friendship, community,

love for and duty to others. What “it renounces [is] the ego’s claim to finality,”(Smith,

21) “a momentary pleasure for a more significant goal.”(Smith, 21)

But ultimately, even this duty will “leave the human spirit unfilled…Faithful

performance of duty brings respect and gratitude from one’s peers. More important,

however, is the self-respect that comes from doing’s one’s share. In the end, though, even

these rewards prove insufficient.”(Smith, 21) Even these prove to be “a revolving door.

Lean on it and it gives, [until] in time one discovers that it is going in circles.”(Smith, 49)

And so over time and with learning, one comes to understand that one already has

what one has been seeking all along, And ultimately one comes to see that one might

achieve in this way the ultimate and eternal goal – that is, liberation from want and

desire, which allows contentment and true satisfaction -- the end of all desire. When we

find that we actually have within us what we wanted all along, i.e. to be, to know, and to

feel love, there and then, one finally becomes “in full what one always was at

heart.”(Smith, 27)

Gandhi gives us the concept of satyagraha – which means, he says, truth (satya)

and firmness (agraha) -- “the force that is born of truth and love.” It is a term he used to

explain his all encompassing conception of ‘passive resistance.’

“It is a force that works silently and apparently slowly. In reality, there is

no force in the world that is so direct or so swift in working. Satyagraha is

a force which, if it became universal, would revolutionize social ideals

and do away with despotism and ever growing militarism under which the

nations in the west are growing and being crushed to death… It is totally

untrue to say that satyagraha is a force to be used only by the weak so

long as they are not capable of meeting violence by violence…This force is

to violence, and therefore to all tyranny, all injustice, what light is to

darkness. It is desire to do the opponent good…. Even if the opponent

plays him false twenty times, the satyagraha is ready to trust him the

twenty-first time, for an implicit trust in human nature is the very essence

of his creed... A satyagraha is nothing if not instinctively law abiding, and

it is his law-abiding nature which exactly from him implicit obedience to

the highest law, that is, the voice of conscience which overrides all other

laws.”

Everyone is bound to learn eventually, ancient Hindus say, that what we really

want is simply to be, to know, and to feel joy, which behooves us to avoid that which

diminishes these. But again, not everyone will learn the true means to these ends in a

single lifetime, or perhaps even many, for one must do the work to gain the insight.

And so we may advance by fits and starts as we zig-zag our way toward our

higher potentials, sometimes even by way of some steps forward, and some steps back.

Whereas the unwise will put lower and selfish pleasures before all else, they will find

them impossible to satisfy, and perhaps even make themselves miserable in the process.

But if we are wise, we will want pleasure in proper proportion, and thus find such desires

easy to satisfy.

So it is that the ancients teach their young that, rather than deny the value of lower

or base pleasures, we ought to recognize that wants are the means by which we grow to

understand higher goods. So we ought to learn to want what is actually good for us.

Again, there is nothing wrong with seeking pleasure, as long as we do so intelligently!

That is, according to the rules of morality, the “moral law of cause and effect,” that

commits us to “complete personal responsibility” in a “completely moral

universe.”(Smith, 49)

On Higher Happiness

And so, only by learning from of the consequences of our choices will we

advance through the stages of desire and renunciation of what seems to be good for us,

toward a higher understanding of what is truly good for us. Until we ultimately discover

the truth of reality, as the song says -- “It’s not having what you want, but wanting what

you have” that matters.

Here then one can finally see that the very condition of one’s inner world is the

result of how one has lived. For this is where karma takes its direct and inexorable toll.

“The present condition of each interior life – how happy it is, how confused or serene,

how much it sees – is an exact product of what it has wanted and done in the past.

Equally, one’s present thoughts and decisions determine one’s future

experiences.”(Smith, 49)

“Each act that is directed upon the world reacts to oneself, delivering a chisel

blow that sculpts one’s destiny.”(Smith, 49) And so our every choice feeds back on us,

such that even how much one sees is a product of one’s karma; thus, one’s very

intelligence or ignorance will be a manifestation of the rewards of one’s way of living. It

is in this way that the ancients understood how it is that there are many paths to the same

summit.

And perhaps only at this point does the human spirit notice that it was never alone

in this journey, but has been traveling with a “constant companion, the Friend who

understands,” that is “the god within.”(Smith, 50) Which perhaps explains why the Hindu

sages proclaimed we should, “Leave all and follow the Self! Enjoy its inexpressible

riches.”(Upanishads, Smith, 40)

However, our modern western habit of perceiving the objects of our knowledge

from outside-looking-in inclines us to think of the self itself as an object, rather than as

subject, from inside out. “Our word ‘personality’ comes from the Latin persona which

originally referred to the mask an actor donned as he or she stepped onto the stage. The

mask depicted the actor’s role, while behind it the actor remained hidden and

anonymous.”(Smith, 27) Likewise, the “word ‘my’ always implies a distinction between

the possessor and what is possessed.” So when I “speak of my body, my mind, and my

personality, [this] suggests that in some sense I think of myself as distinct from them as

well.”(Smith, 27)

And so a proper understanding of the self in eastern thought compels us to

reconsider our ways of knowing, so to see the self as the ancients conceived it – not as

something to be looked at, but as that which we see through. As the equally ancient

Taoists put it, “not merely, ‘things perceived,’ but ‘that by which we perceive.’”(Tao Te

Ching, Smith, p.131)

The “enduring Self” that the ancient understood to be the self-same with God, is

not “the transient self” that comes to mind when we, in the west, consider our ‘self-

interest’.(Smith, 27) We must “distinguish between the surface self that crowds the

foreground of attention and the larger self that is latent and out of sight.”(Smith, 27)14 For

knowledge of this deeper self “is identical with being.”(Smith, 27)

As we’ve said, the earliest Christians also seem to have understood that “to know

oneself, at the deepest level, is simultaneously to know God: this is the secret of gnosis,”

Elaine Pagels tells us. “Self–knowledge is knowledge of God; the self and the divine are

identical.”(The Gnostic Gospels) And ‘The way to ascend onto God is to descend into

one’s self’.”(Suzuki, p. 43) But we might wonder if such insights, that we at its

foundation, have been so neglected as to weaken that foundation.

At any rate, the Hindus call this deep self Atman,(Smith, 50) and the universe that

it traverses, the Sanskrit word for which is Brahman. And with this complex conception

of Atman we only begin to glimpse the grand truth of the interactive universe we inhabit.

In Hinduism, “the world’s metaphysical status” is, “one between dual and non-dual

points of view,” which “divides the personal from the transpersonal view.”(Smith, 52)

The word Brahman derives from dual origins, including “br, to breathe, and brih,

to be great.”(Smith, 47) Great breadth! And its attributes include “sat, chit, and ananda;

God is being, awareness, and bliss.”(Smith, 47) Bere again, we come up against the limits

of language, for what is finite cannot describe the infinite. But again, “words and

concepts are inevitable, for without them we get nowhere. They are indicators that point

us in the right direction without delivering us to our destination.”(Smith, 47)

And so we resort again to metaphors, pictures, and stories.

If we wish to put the life span of Brahman into human time scales, it would be

“staggering,” Smith says. But try this:

“The Himalayas are made of solid granite. Once every thousand years a

bird flies over them, brushing the range with its wings. When by this

process the Himalayas have been worn away, one day of a cosmic cycle

[or breadth] will have elapsed.”(Smith, 52)

“Nirguna Brahman is the ocean without ripple; Saguna Brahman that same ocean

alive with waves and swells. In the language of theology, the distinction is between

personal and transpersonal conceptions of God. Hinduism includes superb champions of

each view, but on the whole accepts them both, in something of the way scientists accept

both wave and particle depictions of matter.”(Smith, 47)

Ancient Hindus understood that “the world appears the way we see it, but that is

not the way it really is.”(Smith, 53) Like dreams, if we ask what they are, “our answer

must be qualified. They are real in [the sense] that we have them, but most of their

images do not exist in the real – i.e. waking – world. Strictly speaking, a dream is a

psychological construct, a mental fabrication.”(Smith, 53) (We will see this distinction

14

again in Aristotle’s comparison of primary to secondary substance, the first of which

exists prior to us, while the second exists because of us.)

Hence the reason the Hindus say that the “middling world” is all maya (which

comes from the same root as magic, “seductive in the attractiveness with which it

decorates the world,”(Smith, 53) “deceptively tricky in passing off its multiplicity,

materiality and dualities as ultimate”(Smith, 55), and “trapping us for a long time within

it…postponing our wish to journey on.”(Smith, 53) Thus, the world is also lila (“the play

of the divine in its cosmic dance”(Smith, 55). Like a children’s “game is its own

reward.”(Smith, 53)

It is for this reason that Hinduism is lighthearted. “It is no accident that the only

art form India did not produce was tragedy.”(Smith, 55) As Deepak Chopra puts it, the

ultimate meaning of enlightenment is to lighten up.

This “middling world” is somewhere between better and worse worlds (heavens

and hells) and is “woven of good and evil, pleasure and pain, knowledge and

ignorance.”(Smith, 52) And just as “the fourth grade remains the fourth grade while

different pupils move through it,”(Smith, 52) so this world remains a hill to be climbed

by all, “a training ground for the human spirit.”(Smith, 52) And despite all our utopian

dreams of a fully realized paradise on earth, it is beyond hope that all humans will

become fully realized and reach the summit at once. Each being is in process of

becoming, and the best the world can do is to help facilitate that process, beginning with

the ways in which we educate our young.

Paradise – Life As It Could Be?

My name was a gift from my mother. My grandfather was Moses Levi Paradise.

He ran our small town bottling works in northern Wisconsin, where *. But he invented

toys for his grandchildren in his spare time, and was a man of few words.

My parents owned a small downtown restaurant – Hunt’s Grill. My father cooked

while my mother baked, and I free-loaded every day after school. My dad rented a body

shop across the alley from the grill, where he designed and built off-road vehicles in his

spare time, and snowmobiles, before their time,.

In hindsight, it may have been my father and grandfathers who inspired me to

dream about what is still and always possible in this world, but they were enabled in

these pursuits by my mother and grandmothers, who didn’t have spare time to be

creative, at least not in ways most would notice. But that doesn’t mean these women

didn’t dream, or invent, or create – only, as Virginia Woolf rightly observed has been the

condition of women throughout time, they “didn’t have a dog’s chance” of having it

noticed in the world such as it has been for most women. Those of us who loved them

noticed though.

So this is reason enough to hold fiercely to my mother’s maiden name. Gratitude

to all those unnamed women who came before would reason enough, but that she asked

me to carry it on cinched it, of course. But it is an added gift that the word paradise

represents such a beautiful metaphor – and can recall for us, in its full etymology, not

merely what is past, but what is still and always possible in this world.

This practice of examining the senses in which we use our terms is close to the

heart of true philosophy – but widely neglected in our time. As is the dialectic

understanding that reality looks different from different points of view, which is why

words can come to mean different

things to different people.

The word paradise is a concept

with its roots in many cultures, tailored

by each to in its own mythology, seen

by all as something of an ideal,

uncorrupted, pristine, life and nature in

its healthy and harmonious state of

being. For some, it summons images of

life before the fall. For others,

especially older wisdom traditions, it

was not a lost ideal, but a target to be

found, a potential to be actualized.

The word paradise is a good

example of single word that has come

to mean different things to different

people, and is understood in different

senses that are worthy of more

consideration than we tend to give to the words we use.

The word paradise entered the English language via the French paradis, which

was inherited from the Latin paradisus. The Romans had taken it from the Greek

parádeisos (παράδεισος), which originally, came from the Old Persian root, Pardis -meaning a place that uplifted and protected the human spirit, such as a beautiful walled

garden where life flourished in a lush oasis. Though rare, the ideal of paradise was

understood in this sense as an earthly place, what humans saw as potential here on this

beautiful planet – a state of peace, prosperity, and happiness, but not necessarily of

luxury and idleness.

Eventually, the Abrahamic faiths associate it with the Garden of Eden -- the

perfect state of existence prior to the ‘fall from grace’ – the world before it was tainted by

evil, before it was dominated by injustice. In this, it was a target, a potential that might

still be actualized, though good leaders were needed to hit the mark.

The Celts too (who called it Mag Mell), and the Norse (who called it Valhalla)

considered paradise, not an afterlife destination, but an earthly realm that could be

reached by the living by means of honor and glory. The Egyptians (who called it Aaru)

and Native Americans (who called it simply Mother Earth) considered the concept of

paradise to be an ideal earthly condition, and eternal hunting and fishing grounds filled

with an abundance that could not be depleted.

This widespread connotation of paradise as an earthly land of plenty, an existence

beyond want, filled with the intrinsic pleasures of music, dance, and love -- is a powerful

counter-image to many of the miseries of human civilization, from which escape and

relief proves so difficult or so many, except by death. It may be difficult for many of us,

especially in what we call developed nations today, to conceive of the suffering that is

still ubiquitous throughout the world, as it has always been, throughout the rest of the

world in all times and places. But it was from the reality of this condition that the ideal of

a paradise beyond these earthly limits began in the minds of those who were not close to

the earthly Pardis garden, not privy to the comfort and contentment of earthly realms

often usurped by the few, and who longed for this harmonious and fair existence to which

the souls of the deserving might somehow find their way. Thus, the concept of paradise

became conflated with the idea of heaven, able to be reached only by the worthy after

death.

Given the reality of

injustice in so many human

cultures, along with the

disparity between wealth and

poverty this entails, this

conception of paradise as

heaven came to be associated

with a prior and afterlife, to

which the worthy might

return when the day comes

they could transcend, not

only

their

physical

limitations, but also the

suffering of poverty and

deprivation

that

human

existence so often entails. Who is and is not worthy of entrance into this afterlife has been

the subject of much speculation across many cultures for many centuries, and paying the

price of that entrance has kept generation after generation jumping through hoops set up

by those who claim to hold the keys to this heavenly place.

It was Buddha, himself born into relative splendor in that early tradition of the

Hindu sages, who brought this blissful realm back to earth, teaching that salvation in this

life is the best we should hope for. The Vedic Indians knew that there is suffering in

every life, and longed for a bliss beyond the body, but escape from the karmic cycle of

life was understood as psychological maturity and liberation from desire, which was not a

place beyond this life, Buddha taught, but a state of being within it. Still, the dependence

on an afterlife (upon which the fixed caste system was founded by later Brahmins), might

be seen as a mere rationalization of earthly injustice. And some might wonder if the later

Christian emphasis on ‘fallen man’ and the difficulty of achieving justice in this world

might actually have had the same source. We tend to think of this as long ago in time, a

decision made early in the childhood of human history, but it is more likely to be a state

that exists early in every life, and so not long lost, as we tend to suppose, but rather, born

fresh with every generation., though maintained only by those who learn how.. Hence the

importance of teaching the young well….good habits from the start, not selfish. Self

interest and selfish are not the same, after all. True self interest lies in what’s actually

good for us, so ancient cultures taught their young, from the start, to be good…and

assumed that goodness from the start. Latter day notions of ‘fallen man’ might have

shocked those who understood the power of self-fulfilling prophesy….better than we do

today.

Heaven or paradise is not unlike the conception of ‘best existence,’ in this sense,

as seen in the Zoroastrian Avesta, or simply the highest function of a healthy human

being in a healthy human society, as Aristotle conceived, in which each of us lives up to

our better selves.

The Greeks (by which we mean the best of them, not the rest of them) knew that

they did not know, and with their great sage, Socrates, the father of philosophy, they

understood that whatever else we might want to believe (or have others believe), humans

simply cannot know on this side of death what will be found on the other side. We may

have beliefs, but because people are willing to believe many things, some of which

stretch logic and are contradicted by actual evidence, beliefs, in and of themselves, are

not knowledge. They may actually turn out to be true beliefs, in the end, and "True

opinion [may be] as good a guide as knowledge for the purpose of acting rightly,"(97b-c)

Socrates admits. But true opinions "are not worth much until you tether them by working

out the reason...once they are tied down, they become knowledge, and are stable. That is

why knowledge is something more valuable than right opinion. What distinguished one

from the other is the tether."(98)

For this reason alone, there’s no need to fear death, as Socrates showed by the

noble way in which he himself faced his execution at the hands of his political enemies

who had usurped the first democracy. Indeed, “for all we know, death may be the greatest

good,” Socrates said.(*) But, not knowing what’s to come, we need only live as well as

possible while we’re alive. Indeed, perhaps we only fear death at all if we think our just

reward will not be good? Because we do indeed have different just deserts, death itself

has different meanings for different people. So one way to eliminate fear of death might

be to change our just deserts, as the Hindus taught.

Of course, there is the other side of this view: there are those who, seeing no good

in this life, actually crave death, thinking it the cessation of their suffering, and perhaps

even believing it to be a better place. The ancient view can help with this too, for if we

understand life’s suffering to be opportunities for learning, chances to advance in our

spiritual growth, and add to this the understanding that we have come a very long way to

get this far, to get to this opportunity, then death – especially willful death – would

represent only the need to start all over again, not just in another life, but perhaps even in

the cycle of lives. Throwing away a life that represents the culmination of perhaps many

lives that it took to get this far, and which offers us opportunities that many others who

suffer more would trade anything for, in the process ignoring so much good that need

only be realized by our efforts, might be understood in this light as the equivalent of

slapping the universe in the face. Whereas seeing life as the opportunity that it is allows

us to appreciate it more fully, suffering and all.

There is a scene in Thorton Wilder’s play, Our Town, in which a young woman

who had died in childbirth at only eighteen is given a chance by her spiritual guide to go

back to revisit just one day of her life. Her first impulse is to choose a very special day,

her sixteenth birthday, or maybe the day of her marriage. But her guide warns her to

choose a perfectly ordinary day, for even that will seem so truly miraculous as to be

overwhelming…through the eyes she now has, able to see the good of living for all it’s

worth. The same experience is offered us when someone we love dies, or leaves us; what

we wouldn’t give for just one more day? As the old saying goes, we hardly know what

we’ve got until it’s gone. If we could only remember and take the time to ‘see’ what we

truly have through the eyes we would have if and when those blessings are gone, then we

would truly love every day of our lives more deeply, and we would be able to recognize

our challenges as the blessings they ultimately turn out to be.

Here again we see the power of words. When most people hear the word

paradise, they think of uncorrupted innocence and harmony…in one form or another.

And with it comes the conflated idea that all such times are past, that such idealized

conceptions are mere memories, at best, like dreams of lost childhoods that were simply

too good to last, and thus no longer potential for ‘fallen’ humanity.

Poor Plato is widely ridiculed for suggesting that such utopian potentials are

actually realistic, indeed, born again fresh with each generation, perhaps even with every

new life. But we’ve neglected and almost forgotten this too, and instead have drawn

broad conclusions with far reaching implications about fallen human nature and what is

and is not possible, either for individuals, or for human kind. Passing on a belief in our

inevitable sinfullness, humans have abdicated their responsibility for teaching the young

right reason and choice of virtue, and instead raised them to replicate the very

characteristics we teach them come naturally – leaving them not choice, says Socrates,

but to play along. And so, as if by self-fulfilling prophesy, selfishness, greed, and the