Using Quotations in Your Writing

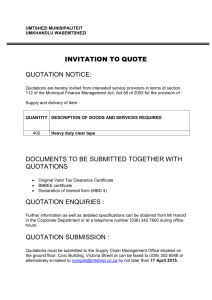

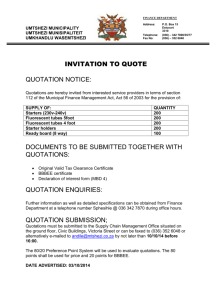

advertisement

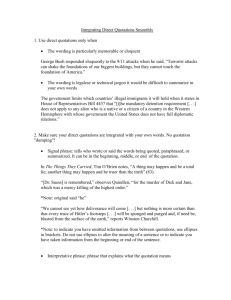

Using Quotations in Your Writing Mrs. Snipes Troy High School In writing about literature, use direct quotations from the text(s) you are analyzing. They help to establish your critical authority and they have stronger weight than the other forms of evidence, such as paraphrase and summary. Quotations also enliven an essay by varying your style with samples of the author’s. On the other hand, quotations should not be overused, so that the paper becomes a patchwork of quoted passages, stitched together with a few transitional sentences. If the excerpts can speak for themselves, the reader may just as well read the original. Quotations should be brief and emphatic, reserved for reinforcing a main point or demonstrating a feature of the author’s style. Principles for effective use of Quotations in Writing: 1. Limit most quotations to single words or phrases: To reinforce a point: The Misfit is a ruthless killer. Yet, surprisingly, when he removes his glasses, his eyes seem “pale and defenseless-looking” (O’Connor 1135). To comment on the author’s style: Laertes says that the “folly” of his tears at Ophelia’s death “drowns” his “speech of fire” (Hamlet, 4.6.186 – 192). This metaphor not only expresses his feeling of helplessness, it alludes to the way his beloved sister died—by drowning. Note: Be especially wary about quoting passages over four lines long in your paper, which have to be indented and single-spaced. A useful guideline is to include no more than one long quotation for every 500 words (or two typed, double spaced pages) of a paper. Such long excerpts should not be wasted on summarizing the plot or on repeating paraphrased ideas. Ineffective use of long quotation: “‘Now look here, Bailey,’ she said, ‘see here, read this,’ and she stood with one hand on her thin hip and the other rattling the newspaper at his bald head. ‘Here this fellow that called himself the Misfit is aloose from the Federal Pen and headed toward Florida and you read here what it says he did to these people. Just you read it. I wouldn’t take my children in any direction with a criminal like that aloose in it’” (“A Good Man is Hard to Find” 1123). The grandmother begins by trying to persuade her son, Bailey, into changing his plans of going to Florida for the weekend. She does not feel it is safe for the family to go to Florida because the criminal is heading there. Here the writer’s “commentary” is really a monotonous repetition of the ideas in the passage. Effective Commentary: Early on in the story, we get a clear sense of the grandmother’s methods. She wants the family to vacation in Tennessee rather than Florida. She uses forms of persuasion that she thinks are subtle: seizing on a sensationalist news story, looming over her grown son, prodding his sense of fatherly responsibility. She would say that she has the family’s best interests at heart. But to the long-suffering Bailey, she is a bully and an irritant. 2. In introducing a quotation, make the context clear—by describing the situation, the speaker, or both. Context Unclear: Juliet does not want to obey. “When I do, I swear / It shall be Romeo, whom you know I hate, / Rather than Paris” (3.5.122-24). Context Clear: Secretly married to her family’s enemy, Juliet rejects her mother’s order to marry the gallant young count: “When I do, I swear / It shall be Romeo, whom you know I hate, / Rather than Paris” (3.5.122-24). Note: A slash, with a space before and after it, is used to separate lines of verse and poetry. If the quotation is longer than three lines, indent it to ten spaces and single space it, but do not use slashes. 3. In introducing a quotation, do not call attention to the page or act number. That creates a false emphasis, and sometimes confuses literature and life. Instead, describe the situation. Wrong: On page 48, Nick first meets Gatsby, whom he describes as “an elegant young roughneck.” Right: It is at one of the wildly extravagant parties that Nick first meets Gatsby, whom he describes as “an elegant young roughneck (Fitzgerald 48). Wrong: Near the end of scene three, Macbeth describes the king’s “gashed stabs” and Lady Macbeth faints. Right: As Macbeth is describing the murdered king, with his “gashed stabs,” Lady Macbeth faints (2.3.107-21). Note: The exception is if the location in the literature is relevant to the point being made. Act III, in Hamlet as in most of Shakespeare’s tragedies, marks the climax of the action. 4. Make the transition between your words and the author’s clear and smooth. No transition: Juliet’s father is very angry. “Out, you green-sickness carrion” (3.5.157). Smooth transition: Juliet’s father is furious. He curses at her in morbid terms: “Out, you green-sickness carrion” (3.5.157). Smooth transition: Juliet’s father is so angry that he calls his young daughter “greensickness carrion” (3.5.157). In other words, use the introduction of a quotation to focus on its salient qualities, to support your interpretation. Note: Before a complete sentence in quotation marks, a colon ( : ) or a comma is needed. No punctuation is used before a word or phrase, as in “green-sickness carrion.” 5. Make the structure of your sentence conform to that of the author. Original: “I have a speech of fire, that fain would blaze / But that this folly drowns it” (4.6.191-92). By beginning the quotation at a convenient point: Laertes says that he could express his outrage in a “speech of fire” (4.6.191). By using an ellipsis (three spaced periods) to show that something from the original has been omitted: Laertes claims that his “speech of fire . . . would blaze” if the “folly” of his grief did not prevent it” (4.6.191-92). By using brackets to change something in the original but without changing the meaning: - a noun to a pronoun, or vice versa The grandmother does not give any details of the crime reported in the newspaper story. She describes it only as “what it says [the Misfit] did to these people.” - a verb or pronoun from one person to another Juliet describes Romeo to her unsuspecting mother as someone whom Lady Capulet “know[s]” that Juliet “hate[s].” Laertes claims that his “speech of fire… would blaze” if the “folly” of his tears did not “drown [ ] it” (4.6.191-92). Note: The empty brackets show that the verb ending has been omitted. - A past tense (in which most stories are written) to the historical present (in which critical essays must be written The grandmother tries to intimidate Bailey by “[standing] with one hand on her thin hip” and “rattling the newspaper” at him. - A puzzling word to a clearer synonym Polonius calls Ophelia “a green [inexperienced] girl” (Hamlet, 1.3. 101). - An error in style or reasoning that occurs in the original, indicated by the Latin word sic, meaning thus. Keats, always an uncertain speller, wrote in one letter, “I shall go to town tommorrow [sic] to see him.” Note: Because sic is a foreign word, it must be italicized. The parentheses should not be used in place of brackets. They indicate an afterthought or minor point from in the original text. The brackets mean “editor’s note”—the signal to the reader that the original thread has been altered. But use brackets and ellipses sparingly; they can be cumbersome and distracting. The preferred method of creating smooth transitions is careful excerpting. 6. The critics own sentence should not be interrupted with a long quotation. That is a form of weak subordination. It makes the sentence awkward and blurs the focus. Awkward: Laertes goes from his usual confidence to a new, helpless sadness in one line, “I have a speech of fire, that fain would blaze / But that this folly drowns it,” which shows how much his only sister’s death has upset him. Smooth: Laertes goes from his usual confidence to a new, helpless, sadness in one line: “I have a speech of fire, that fain would blaze / But that this folly drowns it.” The swift change in his mood shows how much his only sister’s death has upset him. Notice that the revision is not only easier to understand, but more specific. It allows the writer to comment on the question in both the sentence that introduces it and the sentence that follows it. 7. After the quotation, comment further why it is important or how it is worded. Secretly married to her family’s enemy, Juliet rejects her mother’s order to marry that gallant young count: “When I do, I swear / It shall be Romeo, whom you know I hate, I rather than Paris” (3.5.122-24) S.O.S.: Speaker-OccasionSignificance Remember what you learned as a freshman! Frame a quote with a lead-in: speaker and occasion (or context, meaning, what is happening when the quote occurs in the literature) + significance or commentary (meaning, your analysis). As a general rule, you should follow a direct quote with at least two complete sentences of commentary and analysis. Sample of Using Supporting Text in a Literary Analysis Paper: Sita continues to pledge her loyalty when she tells Rama, “I am devoted and faithful to my husband. I have always shared your joy and sorrow, and now I am most desolate. . . Your joy has always been mine to share, and your sorrow”(1156). Here, Sita’s sense of devotion and loyalty in her decision to join Rama in exile reflect the Hindu philosophy of dharma, or sacred duty and righteousness. Her words further reflect her sense of solidarity as she is compelled to join her husband even in the face of adversity. Notice: In the previous example, the quotation has a lead in explaining the speaker and a hint of context. The quotation is woven into the context of the lead-in phrase, is punctuated correctly, and is cited correctly according to MLA parenthetical citations. The quotation is followed by two sentences of meaningful analysis and commentary. Reference the information in this presentation any time you need help incorporating quotations as supporting text in your writing! You’re welcome! Source: Hamilton, Sharon. Solving More Common Writing Problems. Portland, ME. 1997.