Don't stop.

advertisement

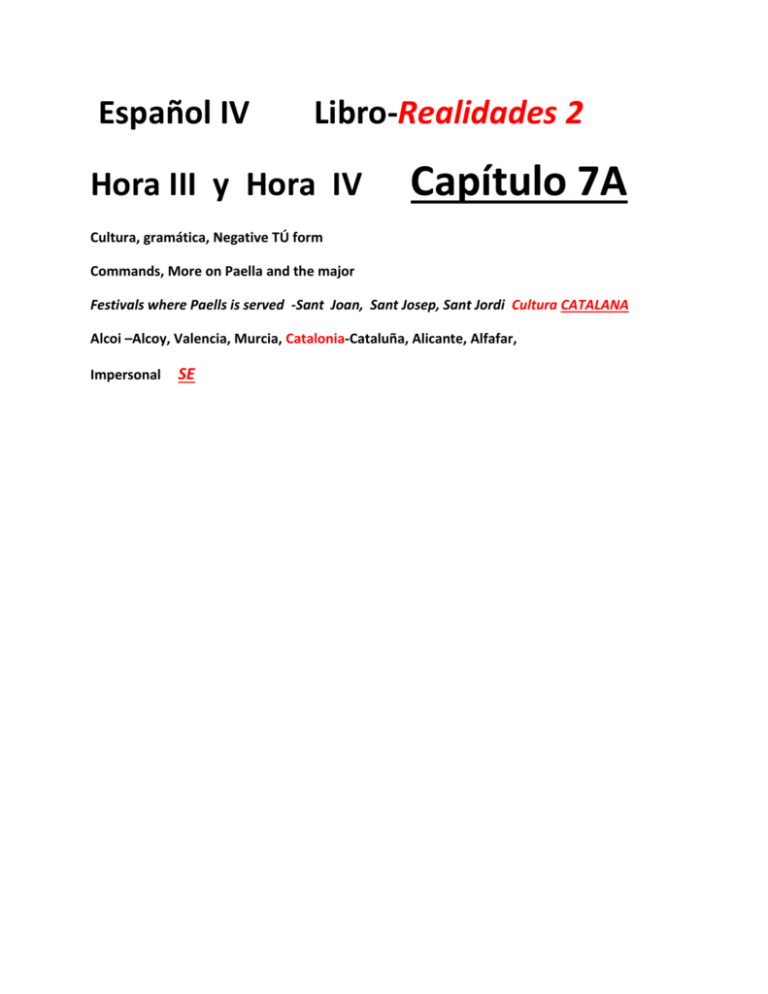

Español IV Libro-Realidades 2 Hora III y Hora IV Capítulo 7A Cultura, gramática, Negative TÚ form Commands, More on Paella and the major Festivals where Paells is served -Sant Joan, Sant Josep, Sant Jordi Cultura CATALANA Alcoi –Alcoy, Valencia, Murcia, Catalonia-Cataluña, Alicante, Alfafar, Impersonal SE fiestas El 8 de noviembre, 2013 META 1.More on Paella from Spain and Spanish Traditions where Paella is celebrated….. Sant josep, Sant Jordi, Sant Joan 2. El Vocabulario de Realidades 2 Capítulo 7A y the impersonal SE Vocabulario Enlatado Realidades 2 Congelado Probar Estufa estufa estufa de leña La olla Sartén Calentar ç Frito Fuego El horno pelar pelar picar el pedazo mezclar añadir añadir Hervir batir Paella (Catalan and Spanish: [paˈeʎa], English approximation /pɑːˈeɪlə/, /ˈpaɪjeɪə/ or /ˈpaɪjɛlə/) is a Valencian rice dish that originated in its modern form in the mid-19th century near lake Albufera, a lagoon in Valencia, on the east coast of Spain. Many non-Spaniards view paella as Spain's national dish, but most Spaniards consider it to be a regional Valencian dish. Valencians, in turn, regard paella as one of their identifying symbols. There are three widely known types of paella: Valencian paella (Spanish: paella valenciana), seafood paella (Spanish: paella de marisco) and mixed paella (Spanish: paella mixta), but there are many others as well. Valencian paella consists of white rice, green vegetables, meat (rabbit, chicken, duck, land snails), beans and seasoning. Seafood paella replaces land animals with seafood and omits beans and green vegetables. Mixed paella is a free-style combination of land animals, seafood, vegetables, and sometimes beans. Most paella chefs use calasparra or bomba rices for this dish. Other key ingredients include saffron and olive oil. Etymology Paella is a Catalan/Valencian word which derives from paelle for pan, which in turn comes from the Latin word patella for pan as well. Patella is also akin to the modern French poêle[citation needed], the Italian padella and the Old Spanish padilla. Valencians use the word paella for all pans, including the specialized shallow pan used for cooking paellas. However, in most other parts of Spain and throughout Latin America, the term paellera is more commonly used for this pan, though both terms are correct, as stated by the Royal Spanish Academy, the body responsible for regulating the Spanish language. Paelleras are traditionally round, shallow and made of polished steel with two handles. HISTORY Uncooked bomba rice The people of Moorish Spain often made casseroles of rice, fish and spices for family gatherings and religious feasts, thus establishing the custom of eating rice in Spain. This led to rice becoming a staple by the 15th century. Afterwards, it became customary for cooks to combine rice with vegetables, beans and dry cod, providing an acceptable meal for Lent. Fish always predominated with rice along Spain's eastern coast. Valencian paella On special occasions, 18th century Valencians used paelleras to cook rice in the open air of their orchards near lake Albufera. Water vole meat was one of the main ingredients of early paellas, along with eel and butter beans. Novelist Vicente Blasco Ibáñez described the Valencian custom of eating water voles in Cañas y Barro (1902), a realistic novel about life among the fishermen and peasants near lake Albufera. Living standards rose with the sociological changes of the late 19th century in Spain, giving rise to reunions and outings in the countryside. This led to a change of paella's ingredients as well, these being rabbit, chicken, duck and sometimes snails. This dish became so popular that in 1840 a local Spanish newspaper first used the word paella to refer to the recipe rather than the pan. The most widely used, complete ingredient list of this era was as follows: short-grain white rice, chicken, rabbit, snails (optional), duck (optional), butter beans, great northern beans, runner beans, artichoke (a substitute for runner beans in the winter), tomatoes, fresh rosemary, sweet paprika, saffron, garlic (optional), salt, olive oil and water.[11] (Poorer Valencians, however, sometimes used nothing more than snails for meat.) Valencians insist that only these ingredients should go into making modern Valencian paella. Seafood and mixed paella Traditional preparation of paella On the Mediterranean coast, Valencians used seafood instead of meat and beans to make paella. Valencians regard this recipe as authentic as well. In this recipe, the seafood is served in the shell. A variant on this is paella del senyoret which utilizes seafood without shells. Later, however, Spaniards living outside of Valencia combined seafood with meat from land animals and mixed paella was born. During the 20th century, paella's popularity spread past Spain's borders. As other cultures set out to make paella, the dish invariably acquired regional influences. Consequently, paella recipes went from being relatively simple to including a wide variety of seafood, meat, sausage, (even chorizo)[15][16] vegetables and many different seasonings.[17] However, the most globally popular recipe is seafood paella. Throughout non-Valencian Spain, mixed paella is very popular. Some restaurants in Spain (and many in the United States) that serve this mixed version, refer to it as Valencian paella. However, Valencians insist only the original two Valencian recipes are authentic. They generally view all others as inferior, not genuine or even grotesque. Basic cooking methods According to tradition in Valencia, paella is cooked by men over an open fire, fueled by orange and pine branches along with pine cones. This produces an aromatic smoke which infuses the paella. Also, dinner guests traditionally eat directly out of the paellera. Some recipes call for paella to be covered and left to settle for five or ten minutes after cooking. A Spanish saying describes paella as "mal guisao y bien reposao" ("poorly cooked, but well settled"). Valencian paella Valencian paella This recipe is standardized[18][19][20][21] because Valencians consider it traditional and very much part of their culture. Rice in Valencian paella is never braised in oil, as pilaf, though the paella made further southwest of Valencia often is. Heat oil in a paellera. Sauté meat after seasoning with salt. Add green vegetables and sauté until soft. Add garlic (optional), grated tomatoes, beans and sauté. Add paprika and sauté. Add water, saffron (and/or food coloring), snails and rosemary. Boil to make broth and allow it to reduce by half. Add rice and simmer until rice is cooked. Garnish with more fresh rosemary. Seafood paella Seafood paella Recipes for this dish vary somewhat, even in Valencia. Below is a recipe by Juanry Segui, a prominent Valencian chef. Make a seafood broth from shrimp heads, onions, garlic and bay leaves. Heat oil in a paellera. Add mussels. Cook until they open and then remove. Sauté Norway lobster and whole, deep-water rose shrimp. Then remove both the lobster and shrimp. Add chopped cuttlefish and sauté. Add shrimp tails and sauté. Add garlic and sauté. Add grated tomato and sauté. Add rice and braise in sofrito. Add paprika and sauté. Add seafood broth and then saffron (and/or food coloring). Add salt to taste. Replace the deep-water rose shrimp, mussels and Norway lobster. Simmer until rice is cooked. Mixed paella Plate of paella with Aioli There are countless mixed paella recipes. The following method is common to most of these. Seasoning depends greatly on individual preferences and regional influences. However, salt, saffron and garlic are almost always included. Make a broth from seafood, chicken, onions, garlic, bell peppers and bay leaf. Heat oil in a paellera. Sear red bell pepper strips and set aside. Sear crustaceans and set aside. Season meat lightly with salt and sauté meat until golden brown. Add onions, garlic and bell peppers. Sauté until vegetables are tender. Add grated tomatoes and sauté. Add dry seasonings except for salt. Add rice Braise rice until covered with sofrito. Add broth. Add salt to taste. Add saffron (and/or food coloring) and mix well. Simmer until rice is almost cooked. Replace crustaceans. Continue simmering until rice and crustaceans are finished cooking. Garnish with seared red bell pepper strips. For all recipes Paella usually has a layer of toasted rice at the bottom of the pan called socarrat in Spain. This is considered a delicacy there and is essential to a good paella. The toasted rice develops on its own if the paella is cooked over a burner or open fire. If cooked in an oven, however, it will not. To correct this, place the paellera over a high flame while listening to the rice toast at the bottom of the pan. Once the aroma of toasted rice wafts upwards, remove it from the heat. The paella must then sit for about five minutes (most recipes recommend the paella be covered with a towel at this point) to absorb the remaining broth. Competitions and records Guinness World Record 1992 in Valencia It has become a custom at mass gatherings in the Valencian Community (festivals, political campaigns, protests, etc.) to prepare enormous paellas, sometimes to win mention in the Guinness Book of World Records. Chefs use gargantuan paelleras for these events. Valencian restaurateur Juan Galbis claims to have made the world's largest paella with help from a team of workers on 2 October 2001. This paella fed about 110,000 people according to Galbis' former website.[26] Galbis says this paella was even larger than his earlier world-record paella made on 8 March 1992 which fed about 100,000 people. Galbis's record-breaking 1992 paella is listed in Guinness World Records. Similar dishes Arròs negre (also called arroz negro and paella Las Fallas ESPAÑA Las Fallas The whole town is literally set ablaze! Sant Josep Las Fallas is undoubtedly one of the most unique and crazy festivals in Spain. Then again, Spain is a country known for its unique and odd fiestas. What started as a feast day for St. Joseph, the patron saint of carpenters, has evolved into a 5-day, multifaceted celebration involving fire Valencia, a quiet city with a population of just over 1 million, swells to an estimated three million flame-loving revelers during Las Fallas celebrations. Las Fallas literally means "the fires" in Valencian. The focus of the fiesta is the creation and destruction of ninots (“puppets” or “dolls”), which are huge cardboard, wood, paper-machè and plaster statues. The ninots are extremely lifelike and usually depict bawdy, satirical scenes and current events. A popular theme is poking fun at corrupt politicians and Spanish celebrities. The labor intensive ninots, often costing up to US $75,000, are crafted by neighborhood organizations and take almost the entire year to construct. Many ninots are several stories tall and need to be moved into their final location of over 350 key intersections and parks around the city with the aid of cranes on the day of la plantà (the rising). The ninots remain in place until March 19th, the day known as La Cremá (the burning). Starting in the early evening, young men with axes chop cleverly-hidden holes in the statues and stuff them with fireworks. The crowds start to chant, the streetlights are turned off, and all of the ninots are set on fire at exactly 12am (midnight). Over the years, the local bomberos (firemen) have devised unique ways to protect the town's buildings from being accidentally set on fire by the ninots: such as neatly covering storefronts with fireproof tarps. Each year, one of the ninots is spared from destruction by popular vote. This ninot is called the ninot indultat (the pardoned puppet) and is exhibited in the local Museum of the Ninot along with the other favorites from years past. Traveler and pyromaniac Janet Morton says, "The scene at Las Fallas is extremely cathartic and difficult to describe, but resembles a cross between a bawdy Disneyland, the Fourth of July and the end of the world!" The street lamps were hung on wooden structures, called parots, and as the days became longer the now-unneeded parots were ceremoniously burned on St. Joseph's Day. Even today the fiesta has retained its satirical and working-class roots, and the well-to-do and faint-of-heart of Valencia often ditch out of town during Las Fallas. Besides the burning of the ninots, there is a myriad of other activities during the fiesta. During the day, you can enjoy an extensive roster of bullfights, parades, paella contests and beauty pageants around the city. Spontaneous fireworks displays explode everywhere during the days leading up to La Crema, but the highlight is the daily mascletá which occurs in the Plaza Ayuntamiento at exactly 2pm. When the string-lined firecrackers are ignited, the thunderous, rythmitic sounds they make can be considered music as the sound intensifies in volume. Those firecrackers timed to fall to the ground literally shake the floor for next ten minutes, as the mascletá is more for auditive enjoyment than visual. Another pyrotechnic cremá takes place in June throughout many towns in Spain. The most famous one is in the city of Alicante, as it celebratres Hogueras de San Juan, "The Bonfires of Saint John." Sant Joan Map of the Fallas Las Fallas in Valencia are distributed are distributed throughout streets of the entire city, for this reason it is important that you are familiar with all the zones so that you do not miss any of the Falles. The furthest area is near the Port Autónom de Valencia, on the Avenida de la Malvarrosa where it meets with Antonio Pons-Cavite. Near the Jardinas del Real, on the intersection of Micer Mascó and Arévalo Vaca, you will find another Falle. The Fallas located at the corner of Monestir de Poblet and Aparicio Albiñana are located just a few blocks from the Falles of Nou Campanar. Now we find ourselves in the center of Valencia, near Paseo de la Pechina where you can find the Falle on display on Na Jordana, several other centrally located Falles are located on Archiduque Carlos, near Parc del Oeste. The other Falles can be found in the Plaza del Pilar and the Plaza de la Merced, another near the Convento Jerusalén, and others on Almirante Cadarso, Reino de Valencia, Sueca and Cuba streets. ALCOY Sant Jordi La Tomatina La Tomatina in 2006 Observed by Buñol, Valencia, Spain Date Last Wednesday in August 2012 date August 29 2013 date August 28 2014 date August 27 2015 date August 26 Frequency annual La Tomatina (Spanish pronunciation: [la tomaˈtina]) is a festival that is held in the Valencian town of Buñol, a town located 30 km from the Mediterranean, in which participants throw tomatoes and get involved in this tomato fight purely for fun. It is held on the last Wednesday of August, during the week of festivities of Buñol. History The most popular of many theories about how the Tomatina started is that, in 1945, during a parade of the "Little Rabbit" some woodland animals were eating all the watermelon so, the people at the parade threw tomatoes at the animals; one missed and hit a person. Then, they started throwing with the tomatoes. The police had to attack everyone. There are many different theories, though. The following year the young people repeated the fight on the same Wednesday of August, only this time they brought their own tomatoes from home. They were again dispersed by the police. After repeating this in subsequent years, the tradition was established. In 1950, the town allowed the tomato hurl to take place, however the next year it was again stopped. A lot of young people were imprisoned but the Buñol residents forced the authorities to let them go. The festival gained popularity with more and more participants getting involved every year. After subsequent years it was banned again with threats of serious penalties. In the year 1957, some young people planned to celebrate "the tomato's funeral", with singers, musicians, and comedies. The main attraction however, was the coffin with a big tomato inside being carried around by youth and a band playing the funeral marches. Considering this popularity of the festival and the alarming demand, 1957 saw the festival becoming official with certain rules and restrictions. These rules have gone through a lot of modifications over the years. Another important landmark in the history of this festival is the year 1975. From this year onwards, "Los Clavarios de San Luis Bertrán" (San Luis Bertrán is the patron of the town of Buñol) organised the whole festival and brought in tomatoes which had previously been brought by the local people. Soon after this, in 1980, the town hall took the responsibility of organizing the festival. Description Preparing the "palo jabón". At around 10 AM, festivities begin with the first event of the Tomatina. It is the "palo jabón", similar to the greasy pole. The goal is to climb a greased pole with a ham on top. As this happens, the crowd works into a frenzy of singing and dancing and gets showered in water from hoses. Once someone is able to drop the ham off the pole, the start signal for the tomato fight is given by firing the water shot in the air and trucks make their entry. The signal for the onset is at about 11 when a loud shot rings out, and the chaos begins.[1] Several trucks throw tomatoes in abundance in the Plaza del Pueblo. The tomatoes come from Extremadura, where they are less expensive and are grown specifically for the holidays, being of inferior taste. For the participants the use of goggles and gloves are recommended. The tomatoes must be crushed before being thrown so as to reduce the risk of injury. The estimated number of tomatoes used are around 150,000 i.e. over 40 metric tons. After exactly one hour the fight ends with the firing of the second shot, announcing the end. The whole town square is colored red and rivers of tomato juice flow freely. Fire Trucks hose down the streets and participants use hoses that locals provide to remove the tomato paste from their bodies. Some participants go to the pool of “los peñones” to wash. After the cleaning, the village cobblestone streets are pristine due to the acidity of the tomato disinfecting and thoroughly cleaning the surfaces. In 2013 the Town Hall of Buñol decided on limiting the fight to 20,000 revellers, with 5,000 tickets allotted to locals of the town of Buñol and 15,000 tickets allotted to foreigners. Tickets cost 10€ per person and are available online. ALFAFAR ESPAÑA ALCOY o ALCOI Alicante IMPERSONAL SE In English, you'll hear statements like "You shouldn't smoke in a hospital" "They say she is very pretty" "One never knows when he will turn up." These are "impersonal expressions". In other words, we don't really have anyone specific in mind when we say "They say..." or "One" or " You". We mean people in general. This is what we mean by "impersonal". Spanish has a slightly different format for expressing this Impersonal voice. Spanish adds the pronoun se in front of verbs to make general statements. Impersonal voice using se will use a singular verb since the se can be replaced by uno ("one"). Here are some examples: How does one say "icecream" in Italian? ¿Cómo se dice "helado" en italiano? You say (one says) "gelato". Se dice "gelato". How do you spell "Valencia"? ¿Cómo se escribe "Valencia"? Notice that the Plural Impersonal (unknown "they") does not use the se : They say that vegetarian pizza is healthy. Dicen que la pizza vegetariana es saludosa. They open the stores at 9:00am. Abren las tiendas a las nueve de la mañana. The "Passive se" is what we call in English "the passive voice". An Active voice is when you have a subject doing something with an active verb. In English a Passive voice has an object having something done to it with or without an identified subject. The Passive Voice in English uses a form of "to Be" with a Past Participle. some examples in English: An Active Voice Construction A Passive Voice Construction Sra. Verde teaches me Spanish. Spanish is taught to me (by Sra. Verde) I purchased the dress. The dress was purchased (by me) I drove my father's new car. My father's new car was driven (by me) The Passive Voice in Spanish is normally formed by using se + the third person singular or plural conjugation of a verb, similar to what we did with the Impersonal se. In Spanish there is not a subject identified or not! look at some examples in Spanish and English: An Active Voice Construction A Passive Voice Construction Spanish Los dependientes Se habla ruso en del almacén hablan ruso. el mercado. The department Russian is spoken English store clerks speak in the shopping Russian. center. Spanish David escribe el libro en italiano. Se escribe el libro en italiano. English David is writing the book in Italian. The book is written in Italian. Spanish La heladería vende una gran cantidad de helado. Se vende una gran cantidad de helado. English The ice cream store sells a large quantity of ice cream. A large quantity of ice cream is sold. Spanish Mis amigos comieron la torta. Se comió la torta. English My friends ate the cake. The cake was eaten. Spanish Los choferes pagan las multas los lunes. Se pagan las multas los lunes. English Drivers pay the fines on Mondays. The fines are paid on -Negative Commands! TÚ Form Al introducir negative Tú form commands Direct negative tú commands are formed by changing the -as ending of the tú form in the present tense to -es and the -es ending of the tú form to -as. for the verb fumar: fumas-->fumes for the verb correr: corres-->corras Let's look at some examples of proper use: ¡No fumes! - Don't smoke! ¡No corras! - Don't run! ¡No duermas! - Don't sleep! ¡No comas! - Don't eat! ¡No vuelvas! - Don't come back! ¡No pienses! - Don't think! No te pares. Don't stop. No cierres la portezuela. Don't close the door. No le des la llave. Don't give him the key. No vengas mañana. Don't come tomorrow. ¡No me hables de él! Don't talk to me about him! Negative TÚ commands is used to tell friends, family members, or young people what NOT to do. Negative TÚ commands is formed by using the present tense YO form as the stem, dropping the -o, and adding the appropriate ending. -es: Negative TÚ command of -AR verbs -as: Negative TÚ command of -ER and -IR verbs NEGATIVE Tú COMMAND FORMS OF -AR VERBS- Drop the -o of the present tense YO form of the verb, and add -es: Yo form-present tense Negative TÚ command tomo (I take/I drink) No tomes trabajo (I work) No trabajes Examples: Negative TÚ command No hables mucho Don't talk a lot. No contestes las preguntas Don't answer the questions. NEGATIVE TÚ COMMAND FORMS OF -ER AND -IR VERBS Drop the -o of the present tense YO form of the verb, and add -as: Yo form-present tense como (I eat) leo (I read) escribo (I write) recibo (I receive) Examples: Negative TÚ command No comas dulces No escribas en el libro Negative TÚ command No comas No leas No escribas No recibas Do not eat candies Do not write on the book COMMAND FORMS OF IRREGULAR YO FORM, STEM-CHANGING AND IRREGULAR VERBS IN THE PRESENT TENSE If the verb has an irregular YO form, it has a stem change or it is an irregular verb in the present tense, it also appears in the TÚ command. Irregular YO form-present tense Pongo (I put) Salgo (I leave) Hago (I do/make) Traigo (I bring) Conozco (I know) Traduzco (I translate) Negative TÚ command No pongas No salgas No hagas No traigas No conozcas No traduzcas Stem-chang. verbspresent tense Recomiendo (I recommend) Duermo (I sleep) Río (I laugh) muevo (I move) Negative TÚ command No recomiendes No duermas No rías No muevas Negative TÚ Irreg. verbs present tense command Digo (I say) No digas Oigo (I hear) No oigas Tengo (I have) No tengas Vengo (I come) No vengas Examples: Negative TÙ command ¡No desobedezcas las reglas! No cierres la ventana ¡No digas mentiras! Don't disobey the rules! Don't close the window Don't say lies! COMMAND FORMS OF VERBS ENDING IN -CAR, GAR, AND -ZAR Verbs ending -car, -gar, and -zar require spelling changes in order to keep the pronunciation. -CAR: C changes to QU -GAR: G changes to GU -ZAR: Z changes to C Infinitive Tocar (to touch/play) Buscar (to look for) Practicar (to practice) Llegar (to arrive) Jugar (to play) Navegar (to navigate) Comenzar (to start/begin) Empezar (to start/begin) Cruzar (to cross) Negative TÚ command No toques No busques No practiques No llegues No juegues No navegues No comiences No empieces No cruces IRREGULAR NEGATIVE TU COMMANDS Dar (to give) No des tu blusa favorita Dont give your favorite blouse Estar (to be) No estés triste Don't be sad Ser (to be) ¡No seas odioso! Don't be mean! Ir (to go) No vayas al parque Don't go to the park NEGATIVE TÚ COMMANDS WITH PRONOUNS With negative commands, direct (d.o.p), indirect (i.o.p) object pronouns and reflexive pronouns go right before the verb. Negative TÚ command No muevas las camas (don't move the beds) No cierres la ventana (don't close the window) No comas los postres (don't eat the desserts) No pongas el mantel (don't put the tablecloth) Negative TÚ command + indirect object pronoun No me traigas la comida ¡No te toques la herida! No le compres el libro No nos contestes la pregunta ¡No les digas eso! Neg TÚ comm+d.o.p No las muevas No la cierres No los comas No lo pongas Do not bring me food Do not touch your wound! Do not buy him/her the book Do not answer us the question Do not tell that to them! Negative TÚ command + reflexive pronoun No te cepilles los dientes No te peines el cabello Do not brush your teeth Do not comb your hair More about the Informal or Tú commands in Spanish When we are with friends, siblings or children, we can order them around more casually. There is a command form for this that is more casual than the Formal Command. We can think of the formation of the Tú commands one of two ways: 1) In the affirmative commands you use the 3rd person (él, ella, usted) singular present tense; - or - 2) In the affirmative commands you use the regular Tú present tense form, but drop the "s". For example, here are some common affirmative Tú commands: Infinitive Tú command COMER COME HABLAR HABLA ESCRIBIR ESCRIBE LEER LEE APAGAR APAGA There are only 8 (eight!) irregular affirmative Tú commands: Decir Di Hacer Haz Ir Ve Ser Sé Poner Pon Venir Ven Tener Ten Salir Sal The negative command form is actually the Tú form of the Present Subjunctive and therefore similar to the Formal commands (except that we add the Tú marker: the "s".) To form the negative Tú commands, you need to first remember how to form the First Person Singular (Yo) in the Present Tense. Remember, if the Yo form is irregular, the command will be irregular. Let's try using an irregular: Hacer. First we start with the infinitive of Hacer: 1. We need to conjugate it in the first person: Hago 2. Now drop the o so we are left with: HAG- 3. Now we add the opposite ending which for Hacer is "-as", and add No because we are making a negative command 4. And we have our negative Tú command: No hagas * By opposite ending we mean add the vowel ending of the other type verb: For verbs that end in "-ar", we add "-es" instead of "-as" and for verbs that end in "-er/ir", we add "-as" instead of "-es" All of the eight irregular affirmative commands follow the above pattern in the negative commands. (Note that Object pronouns always are placed before the verb in all negative commands.) Vean Uds. see below! ¡Di la verdad! Tell the truth! ¡No digas realmente lo que pasó! Don't tell what really happened! ¡Ven acá! Come here! ¡No vengas acá! Don't come over here! ¡Sal del carro! Get out of the car! ¡No salgas del carro! Don't get out of the car! ¡Ten cuidado! Be careful! ¡No tengas cuidado! Don't be careful! ¡Ponlo en la mesa! Put it on the table! ¡No lo pongas en la mesa! Don't put it on the table! ¡Hazlo! Do it! ¡No lo hagas! Don't do it! ¡Sé simpático! Be nice! ¡No seas tonto! Don't be silly! ¡Vete! Get out of here! (Get lost!) ¡No te vayas! Don't go! ESPAÑOL IV HORA III REVIEW BELOW! HORA IV Present perfect Haber plus past particple He estudiado Has estudiado Ha estudiado Hemos estudiado Habéis estudiado Han estudiado Hablar….Hablado Comer….Comido Vivir….Vivido Irregular past participles- Decir- dicho Devolver- devuelto Escribir- escrito Hacer- hecho Morir- muerto Poner- puesto Romper- roto Ver- visto Volver- vuelto Al hacer frases- cada estudiante tiene que hacer una frase con las palabras del repaso del libro… c. Repaso del Presente del Perfecto página 331 d. Indirect Object Pronouns me te le nos os les e. Verbs that use the indirect object página 320- paagina 321 aburrir doler encantar fascinar gustar interpreter molestar parecer quedar f. A Primera Vista repasos La Lista para la clase evaluación y práctica 1. he dicho 2. has oído 3. hemos estudiado 4. he vuelto 5. he comido 6. has abierto 7. han visto 8. he hablado 9. he devuelto 10. habeís escrito I Verbs that use Indirect Object pronouns Aburrir Doler Encantar Fascinar Gustar Importar Interesar Molestar Parecer quedar Indirect Object Pronouns Me Te Le Nos os les a mi a ti a Ud. A él LE A ella A nosotros A vosotros A Uds. A ellos LES A ellas Le - A Ud. A él A ella Les - A Uds. A ellos A ellas II ¡Vocabulario! Aquilar El amor eterno Tu casa - tu cine Robar Arrestar El criminal Capturar La dirreción La directora las personajes principales Hacer el papel de… La actuación Papeles La escena ¿Qué película has visto? Página 318 A Primera Vista página 320 – página 321 Vocabulario y gramática Palabras importantes El Mosquito VIDEOHISTORIA VIDEO y gramactiva Página 322 – Página 323 Actividad… ¿COMPRENDISTE? ACTIVIDAD 3 Página 323 En una hoja de papel escribe las frases de abajo, poniéndolas en ORDEN CRONOLÓGICO. Realidades 2 página 324 Actividad 5 El Crítico nos recomienda… Respuestas solamente Números 1-12 Actividad 11 Página 328 Nos Gustan las películas A continuar 6B 1. Repasar exámenes que ya hicieron…. Explorar las correcciones Explicaciones… The Present Perfect Tense Present Perfect The present perfect is formed by combining the auxiliary verb "has" or "have" with the past participle. I have studied. He has written a letter to María. We have been stranded for six days. Because the present perfect is a compound tense, two verbs are required: the main verb and the auxiliary verb. I have studied. (main verb: studied ; auxiliary verb: have) He has written a letter to María. (main verb: written ; auxiliary verb: has) We have been stranded for six days. (main verb: been ; auxiliary verb: have) In Spanish, the present perfect tense is formed by using the present tense of the auxiliary verb "haber" with the past participle. Haber is conjugated as follows: he has ha hemos habéis han HABER + PAST PARTICIPLE=present perfect Past Participle The past participle will be important in future lessons covering the perfect tenses. To form the past participle, simply drop the infinitive ending (-ar, er, -ir) and add -ado (for -ar verbs) or ido (for -er, -ir verbs). hablar - ar + ado = hablado comer - er + ido = comido vivir - ir + ido = vivido The following common verbs have irregular past participles: abrir (to open) - abierto (open) cubrir (to cover) - cubierto (covered) decir (to say) - dicho (said) escribir (to write) - escrito (written) freír (to fry) - frito (fried) hacer (to do) - hecho (done) morir (to die) - muerto (dead) poner (to put) - puesto (put) resolver (to resolve) - resuelto (resolved) romper (to break) - roto (broken) ver (to see) - visto (seen) volver (to return) - vuelto (returned) Note that compound verbs based on the irregular verbs inherit the same irregularities. Here are a few examples: componer – compuesto describir – descrito devolver - devuelto Most past participles can be used as adjectives. Like other adjectives, they agree in gender and number with the nouns that they modify. La puerta está cerrada. The door is closed. Las puertas están cerradas. The doors are closed El restaurante está abierto. The restaurant is open. Los restaurantes están abiertos. The restaurants are open. The past participle can be combined with the verb "ser" to express the passive voice. Use this construction when an action is being described, and introduce the doer of the action with the word "por." La casa fue construida por los carpinteros. The house was built by the carpenters. La tienda es abierta todos los días por el dueño. The store is opened every day by the owner. Note that for -er and -ir verbs, if the stem ends in a vowel, a written accent will be required. creer – creído oír – oído Note: this rule does not apply, and no written accent is required for verbs ending in -uir. (construir, seguir, influir, distinguir, etc.) Let's add two more flashcards for the past participles, since they will later be used for the perfect tenses: Verb Flashcards Complete List Past Participle Infinitive - ending + ado/ido (hablado, comido, vivido) Past Participle Irregulars abrir (to open) - abierto (open) cubrir (to cover) - cubierto (covered) decir (to say) - dicho (said) escribir (to write) - escrito (written) freír (to fry) - frito (fried) hacer (to do) - hecho (done) morir (to die) - muerto (dead) poner (to put) - puesto (put) resolver (to resolve) - resuelto (resolved) romper (to break) - roto (broken) ver (to see) - visto (seen) volver (to return) - vuelto (returned) You have already learned in a previous lesson that the past participle is formed by dropping the infinitive ending and adding either -ado or -ido. Remember, some past participles are irregular. The following examples all use the past participle for the verb "comer." (yo) He comido. I have eaten. (tú) Has comido. You have eaten. (él) Ha comido. He has eaten. (nosotros) Hemos comido. We have eaten. (vosotros) Habéis comido. You-all have eaten. (ellos) Han comido. They have eaten. For a review of the formation of the past participle. When you studied the past participle, you practiced using it as an adjective. When used as an adjective, the past participle changes to agree with the noun it modifies. However, when used in the perfect tenses, the past participle never changes. Past participle used as an adjective: La cuenta está pagada. The bill is paid. Past participle used in the present perfect tense: He pagado la cuenta. I have paid the bill. Here's a couple of more examples: Past participle used as an adjective: Las cuentas están pagadas. The bills are paid. Past participle used in the present perfect tense: Juan ha pagado las cuentas. Juan has paid the bills. Note that when used to form the present perfect tense, only the base form (pagado) is used. Let's look more carefully at the last example: Juan ha pagado las cuentas. Juan has paid the bills. Notice that we use "ha" to agree with "Juan". We do NOT use "han" to agree with "cuentas." The auxiliary verb is conjugated for the subject of the sentence, not the object. Compare these two examples: Juan ha pagado las cuentas. Juan has paid the bills. Juan y María han viajado a España. Juan and Maria have traveled to Spain. In the first example, we use "ha" because the subject of the sentence is "Juan." In the second example, we use "han" because the subject of the sentence is "Juan y María." The present perfect tense is frequently used for past actions that continue into the present, or continue to affect the present. He estado dos semanas en Madrid. I have been in Madrid for two weeks. Diego ha sido mi amigo por veinte años. Diego has been my friend for 20 years. The present perfect tense is often used with the adverb "ya". Ya han comido. They have already eaten. La empleada ya ha limpiado la casa. The maid has already cleaned the house. The auxiliary verb and the past participle are never separated. To make the sentence negative, add the word "no" before the conjugated form of haber. (yo) No he comido. I have not eaten. (tú) No has comido. You have not eaten. (él) No ha comido. He has not eaten. (nosotros) No hemos comido. We have not eaten. (vosotros) No habéis comido. You-all have not eaten. (ellos) No han comido. They have not eaten. Again, the auxiliary verb and the past participle are never separated. Object pronouns are placed immediately before the auxiliary verb. Pablo le ha dado mucho dinero a su hermana. Pablo has given a lot of money to his sister. To make this sentence negative, the word "no" is placed before the indirect object pronoun (le). Pablo no le ha dado mucho dinero a su hermana. Pablo has not given a lot of money to his sister. With reflexive verbs, the reflexive pronoun is placed immediatedly before the auxiliary verb. Compare how the present perfect differs from the simple present, when a reflexive verb is used. Me cepillo los dientes. (present) I brush my teeth. Me he cepillado los dientes. (present perfect) I have brushed my teeth. To make this sentence negative, the word "no" is placed before the reflexive pronoun (me). No me he cepillado los dientes. I have not brushed my teeth. Questions are formed as follows. Note how the word order is different than the English equivalent. ¿Han salido ya las mujeres? Have the women left yet? ¿Has probado el chocolate alguna vez? Have you ever tried chocolate? Here are the same sentences in negative form. Notice how the auxiliary verb and the past participle are not separated. ¿No han salido ya las mujeres? Haven't the women left yet? ¿No has probado el chocolate ninguna vez? Haven't you ever tried chocolate? In English, you'll hear statements like "You shouldn't smoke in a hospital" "They say she is very pretty" "One never knows when he will turn up." These are "impersonal expressions". In other words, we don't really have anyone specific in mind when we say "They say..." or "One" or " You". We mean people in general. This is what we mean by "impersonal". Spanish has a slightly different format for expressing this Impersonal voice. Spanish adds the pronoun se in front of verbs to make general statements. Impersonal voice using se will use a singular verb since the se can be replaced by uno ("one"). Here are some examples: How does one say "icecream" in Italian? ¿Cómo se dice "helado" en italiano? You say (one says) "gelato". Se dice "gelato". How do you spell "Valencia"? ¿Cómo se escribe "Valencia"? Notice that the Plural Impersonal (unknown "they") does not use the se : They say that vegetarian pizza is healthy. Dicen que la pizza vegetariana es saludosa. They open the stores at 9:00am. Abren las tiendas a las nueve de la mañana. The "Passive se" is what we call in English "the passive voice". An Active voice is when you have a subject doing something with an active verb. In English a Passive voice has an object having something done to it with or without an identified subject. The Passive Voice in English uses a form of "to Be" with a Past Participle. Let's look at some examples in English: An Active Voice A Passive Voice Construction Construction Sra. Verde teaches me Spanish. Spanish is taught to me (by Sra. Verde) I purchased the dress. The dress was purchased (by me) I drove my father's new car. My father's new car was driven (by me) The Passive Voice in Spanish is normally formed by using se + the third person singular or plural conjugation of a verb, similar to what we did with the Impersonal se. In Spanish there is not a subject identified or not! Let's look at some examples in Spanish and English: An Active Voice Construction A Passive Voice Construction Los dependientes Spanish del almacén hablan ruso. Se habla ruso en el mercado. The department Russian is spoken English store clerks speak in the shopping Russian. center. Spanish David escribe el libro en italiano. Se escribe el libro en italiano. English David is writing the book in Italian. The book is written in Italian. Spanish La heladería vende una gran cantidad de helado. Se vende una gran cantidad de helado. English The ice cream store sells a large quantity of ice cream. A large quantity of ice cream is sold. Spanish Mis amigos comieron la torta. Se comió la torta. English My friends ate The cake was Spanish the cake. eaten. Los choferes pagan las multas los lunes. Se pagan las multas los lunes. Drivers pay the English fines on Mondays. The fines are paid on ¡¡¡¡¡¡¡¡ESTUDIEN UDS!!!!!! TAREA TAREA TAREA Present Perfect - Indirect Object Ponouns REVIEW THE STUDY GUIDES ON THE WEBSITE! Studying each day keeps the fear of tests away…. Studying a language is writing things out Especially verb conjugations and vocabulary Beat the storm of learning STUDY Rewrite and summarize notes, verbs conjugations on note cards, index cards, whatever it takes Review at home, write out the conjugation of at least 5 verbs a night!!!!!!! KNOW your verbs! visit you neighbors Visit your friends the verbs, Know them well!!!!! In the city of verbs, visit the neighborhood of conjugations Visit the “houses of AR verbs, er verbs and ir verbs regular And go to the street of irregular verbs as well!!! KNOW YOUR VERBS