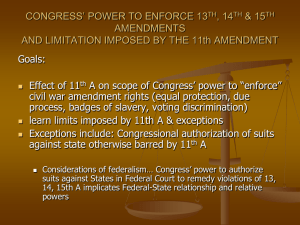

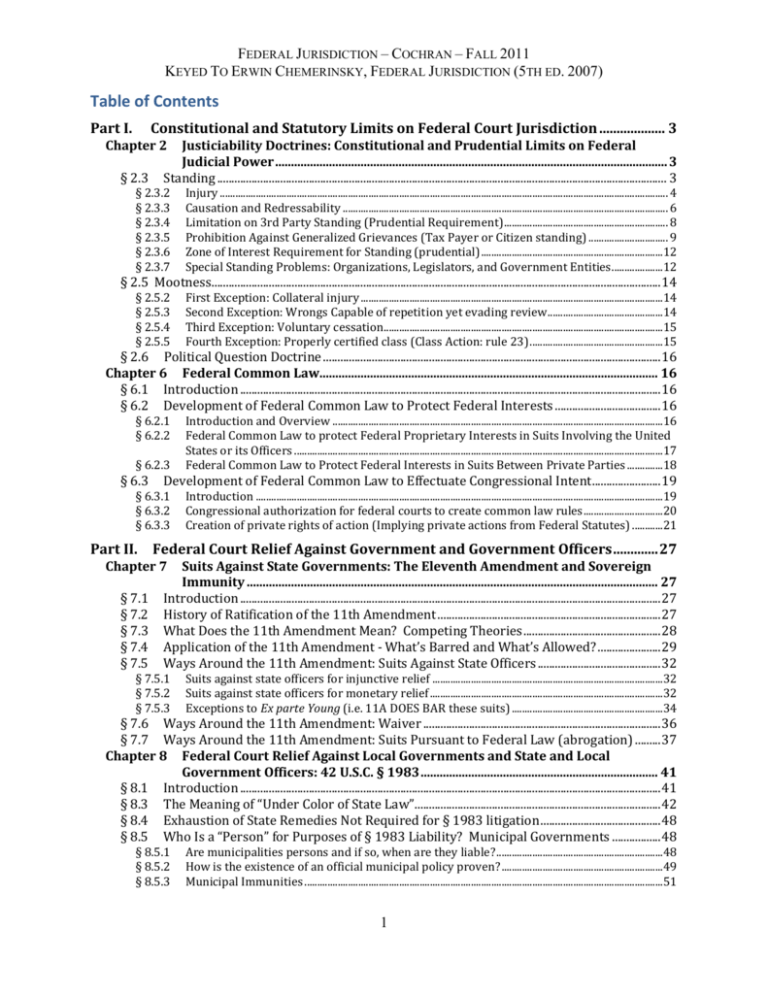

Part I. Constitutional and Statutory Limits on Federal Court Jurisdiction

advertisement