Chapter 31: Soft-Tissue Trauma

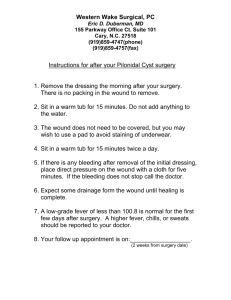

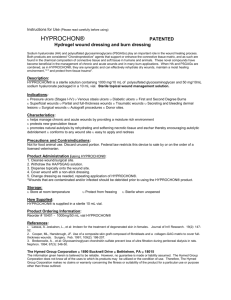

advertisement

Chapter 31 Soft-Tissue Trauma National EMS Education Standard Competencies Trauma Integrates assessment findings with principles of epidemiology and pathophysiology to formulate a field impression to implement a comprehensive treatment/disposition plan for an acutely injured patient. National EMS Education Standard Competencies Soft-Tissue Trauma Recognition and management of − Wounds − Burns • Electrical • Chemical • Thermal − Chemicals in the eye and on the skin National EMS Education Standard Competencies Pathophysiology, assessment, and management of − Wounds • Avulsions • Bite wounds • Lacerations • Puncture wounds • Incisions National EMS Education Standard Competencies Pathophysiology, assessment, and management of (cont’d) − Burns • Electrical • Chemical • Thermal • Radiation − High-pressure injection − Crush syndrome Introduction • The skin is the largest organ of the body. − Injuries are common. − Wound: any injury to soft tissue − Always search for other injuries or conditions before treating soft-tissue trauma. Incidence, Mortality, and Morbidity • Soft tissue can be injured by: − Blunt injury − Penetrating injury − Burns • Soft-tissue trauma is the leading form of injury. Incidence, Mortality, and Morbidity • Death from soft-tissue injury is rare. − Uncontrolled bleeding − Local or systemic infections • Prevention involves simple actions. Structure and Function of the Skin • Skin: complex organ with crucial role in homeostasis − Protects underlying tissue from injury − Aids in temperature regulation − Prevents excessive water loss − Acts as sense organ Structure and Function of the Skin • Significant damage may make the patient vulnerable to: − Bacterial invasion − Temperature instability − Fluid balance disturbances Epidermis • First line of defense • Consists of five layers − Stratum corneum (outermost layer) − Four inner layers of living cells Epidermis Dermis • Tough, highly elastic connective tissue − Composed of: • Collagen and elastic fibers • Mucopolysaccharide gel • Fibroblasts − Subdivided into: • Papillary dermis and reticular layer Dermis • Macrophages and lymphocytes − Part of the inflammatory process − Responsible for combating micro-organisms • Results in increased blood flow, causing redness and warmth Dermis • Specialized structures − Nerve endings − Blood vessels − Sweat glands − Hair follicles − Sebaceous gland Subcutaneous Tissues • Layer beneath the dermis • Mostly adipose tissue − Insulates underlying tissues − Provides a cushion for underlying structures − Provides an energy reserve for the body Deep Fascia • Thick, dense layer of fibrous tissue below subcutaneous tissue − Composed of tough tissue bands − Supports and protects underlying structures Skin Tension Lines • Static tension develops over areas with limited movement. − Lacerations parallel to lines may remain closed. − Larger wounds may be pulled open. − Smaller lacerations perpendicular to tension lines will remain open. Skin Tension Lines • Dynamic tension found over muscle − Open injuries interfere with healing: • Disrupt clotting process • Disrupt tissue repair cycle • An abnormal scar may prompt scar revision surgery. Closed Wounds • Soft tissue is damaged but skin is not broken − Characteristic closed wound is a contusion. Closed Wounds • If small blood vessels are damaged, ecchymosis will cover the area. • If large blood vessels are torn, a hematoma will appear. Courtesy of Rhonda Beck Open Wounds • Characterized by disruption in the skin • Potentially more serious than closed wounds − Vulnerable to infection − Greater potential for serious blood loss Open Wounds Crush Injuries • An injury to the underlying soft tissues and bones • Caused by a body part being crushed between two solid objects © Mark C. Ide Crush Injuries • May lead to compartment syndrome • May lead to rupture of internal organs • External appearance may not represent level of internal damage. − Grotesque injuries may not be primary problem. Crush Injuries • Body’s first responses to vessel injury is localized vasoconstriction. − If vessels are damaged, they may not be able to constrict. • Crush injuries often result in difficult-to-control hemorrhage. Blast Injury • Explosions can result in: − Soft-tissue trauma − Abdominal trauma − Skeletal trauma − Blast lung • Assess the scene for hazards. The Process of Wound Healing • Hemostasis − Vessels, platelets, and clotting cascade must work together to stop bleeding. − The release of chemicals: • Constricts the blood vessels • Activates platelets The Process of Wound Healing • Inflammation − Additional cells enter area for repair. − White blood cells combat pathogens. − Chemotactic factors are released. − Lymphocytes destroy bacteria and pathogens. − Mast cells release histamine. The Process of Wound Healing • Inflammation (cont’d) − Leads to the removal of: • Foreign material • Damaged cellular parts • Invading micro-organisms The Process of Wound Healing • Epithelialization − New epithelial cells move to outer layer of skin to replace those lost in injury. • Area seldom regains previous look. • Function of area may be restored. The Process of Wound Healing • Neovascularization − New blood vessels form to bring oxygen and nutrients to injured tissue. • New capillaries form from intact capillaries. The Process of Wound Healing • Collagen synthesis − Collagen: Tough, fibrous protein in scar tissue, hair, bones, connective tissue − Repair unit is synthesized by fibroblasts. • Cannot restore damaged tissue to former strength Alterations of Wound Healing • Healing does not always follow pattern because there may be: − Infection or abnormal scarring − Excessive bleeding − Slow healing Alterations of Wound Healing • Anatomic factors − Body areas with repeated motion − Relationship of open wound to skin tension lines − Medications − Medical conditions Alterations of Wound Healing • High-risk wounds − Human and animal bites • High risk of infection − Injuries from foreign bodies or organic matter • Do not remove an impaled object in the field. Alterations of Wound Healing • Abnormal scar formation − Excessive collagen formation can occur if healing phases are not balanced, leading to: • Hypertrophic scar • Keloid scar Alterations of Wound Healing • Pressure injuries − Occur from: • Being bedridden • Pressure applied for prolonged periods − Involved tissues are deprived of oxygen. Alterations of Wound Healing • Wounds requiring closure − Include: • Open injuries affecting cosmetic areas • Gaping wounds and wounds over tension lines • Degloving injuries • Ring injuries and skin tears Alterations of Wound Healing • Wounds requiring closure (cont’d) − Open injuries should be closed within 24 hours. − Three types of wound closure: • Primary closure • Secondary intention • Delayed primary closure Pathophysiology of Wound Healing • Infection − Pathogens grow and multiply once they reach body tissues. − Clinical signs may not appear for days. Pathophysiology of Wound Healing • Infection (cont’d) − Visible signs • Pus • Warmth • Edema • Local discomfort • Red streaks Pathophysiology of Wound Healing • Infection (cont’d) − Systemic signs • Fever • Shaking • Chills • Joint pain • Hypotension Pathophysiology of Wound Healing • Gangrene − Caused by Clostridium perfringens • Causes foul-smelling gas − If untreated: • Skin will become necrotic. • Infection may lead to sepsis. Pathophysiology of Wound Healing • Tetanus − Caused by infection from Clostridium tetani − Causes a potent toxin, resulting in: • Painful muscle contractions • Muscle stiffness − Rare because of vaccine Pathophysiology of Wound Healing • Necrotizing fasciitis − Involves tissue death from bacterial infection − Rare, but with high mortality − Treatment includes: • Antibiotic therapy • Surgical debridement Patient Assessment • Skin trauma is rarely life-threatening. − Stay focused on assessment process. • Identify threats to EMS crew. • Identify threats to patient. Scene Size-Up • Address safety first. • Evaluate MOI. − If significant, keep a high index of suspicion. • Determine the number of patients involved. • Protect yourself and patient from bodily fluid. Primary Assessment • Form a general impression. − Determine any life threats. − Check patient and immediate surroundings. − Check for potential injuries to neck and spine. − Evaluate level of consciousness. Primary Assessment • Airway and breathing − Assess immediately. − Correct anything that interferes with airway. − Assess the patient’s breathing. − Take prompt action for compromised breathing. Primary Assessment • Circulation − Assess circulation by: • Palpating a pulse • Palpating and inspecting the skin using CTC − Control of severe hemorrhage with a tourniquet takes precedence. Primary Assessment • Transport decision − Transport patients with significant trauma. − Patients with isolated injuries can often be treated at the scene. Primary Assessment • Significant MOI − Serious trauma indicated by: • Altered level of consciousness • Lack or airway protection or patency • Inadequate breathing • Uncontrolled bleeding • Significant MOI Primary Assessment • Significant MOI (cont’d) − If possibility of serious injury, perform a rapid exam, assessing: • Head and neck • Chest • Abdomen • Pelvis • Lower and upper extremities • Posterior Primary Assessment • Significant MOI (cont’d) − Identify need for attention using DCAP-BTLS: • Deformities • Contusions • Abrasions • Punctures or penetrations • Burns • Tenderness • Lacerations • Swelling Primary Assessment • Significant MOI (cont’d) − Assess areas with: • Alteration in sensation • Uneven temperature • Abnormal muscle tone − Note blood from hidden injuries. − Address any life threats. Primary Assessment • Significant MOI (cont’d) − After assessment, apply a cervical collar. − Decide whether to rapidly transport. − Perform a complete set of vital signs and a SAMPLE history. Primary Assessment • No significant MOI − Isolated extremity trauma does not warrant a fully body exam. − If protocols allow, some patients can be released after treatment on the scene. History Taking • Ask about events leading to injury. • Ask about the last tetanus booster. • Ask about over-the-counter medicines. • Use the mnemonic SAMPLE. Secondary Assessment • Conduct a more thorough examination en route if there is: − A significant MOI − Adequate time − Patient in stable condition Reassessment • Do frequent reassessments en route. − Stable patient—every 15 minutes − Serious condition—every 5 minutes minimum • Obtain and evaluate vital signs. • Check interventions and monitor patient. Reassessment • Complete written documentation. • Note specific injuries, describing wounds. • Note assessment findings for: − Distal neurovascular status − Range of motion − Presence or absence of infection Reassessment • Obtain patient demographic information. • Record any interventions performed, documenting: − Patient’s response − Patient’s understanding − Which provider attended the patient Emergency Medical Care • Basic management principles: − Attend to clinical issues and patient’s feelings. − Control bleeding with direct pressure, elevation, or a tourniquet if necessary. − Document any care provided. Treatment of Closed Wounds • Minimize bleeding and swelling (ICES): − Apply Ice or cold packs. − Apply firm Compression. − Elevate the injured part higher than the heart. − Apply a Splint. Treatment of Closed Wounds • Edema is the body’s way of dealing with injury to soft or connective tissues. • Using ice as early as possible may speed up healing time. Treatment of Open Wounds: General Principles • General principles: − Control bleeding by most effective method. − Keep wound as clean as possible. • Determine injury magnitude, and relay information to the receiving facility. Treatment of Open Wounds: General Principles • If wound is already in healing stage: − Examine edges to see if the wound is closing properly. − Check for signs of infection. Bandaging and Dressing Wounds • Used to: − Cover wound − Control bleeding − Limit motion • Variety of materials used Complications of Improperly Applied Dressings • Always use as sterile technique as possible. − Irrigate open wounds with normal saline. − Apply antibiotic ointment to smaller wounds. − Do not use ointment on larger wounds. Complications of Improperly Applied Dressings • Hemodynamic complications may include continued bleeding. − Apply additional dressings in conjunction with other interventions. − Perform frequent assessments. Complications of Improperly Applied Dressings • Structural elements can be damaged if dressings are too tight. − Assess and readjust if necessary. − When extremity dressings are in place, assess: • Distal pulses • Motor function • Sensation Control of External Bleeding • Bleeding can be characterized by type of blood vessel damaged. − Capillary bleeding—slow flow, bright or dark red − Venous bleeding—slow, steady, darker color − Arterial bleeding—spurts, bright red color Control of External Bleeding • Direct pressure − Allows platelets to form blood clots − Steps for management: • Follow standard precautions. • Maintain airway. • Apply direct pressure with a dry, sterile dressing. • Apply a pressure dressing and gauze. Control of External Bleeding • Direct pressure (cont’d) − If bleeding is not controlled, apply a tourniquet. − Apply high-flow oxygen as necessary. − Monitor serial vital signs, and watch for shock. • If signs of shock arise, transport rapidly. − Assess circulation before and after application. Control of External Bleeding • Elevation − Can substantially slow venous bleeding • Immobilization − Motion disrupts clotting process. − Limit injured extremity movement. − If necessary, apply a splint. Control of External Bleeding • Tourniquet − Especially useful if: • Extremity injury below the axilla or groin is severely bleeding. • Other bleeding control methods are ineffective. Courtesy of Steven Kasser Control of External Bleeding • Tourniquet (cont’d) − Follow standard precautions. − Hold direct pressure over bleeding site. − Place tourniquet above the bleeding site. − Click the buckle into place. − Turn the tightening dial clockwise until pulses are no longer palpable distal to the tourniquet. Control of External Bleeding • Tourniquet (cont’d) − To release the tourniquet, push the release button and pull the strap back. − If a commercial tourniquet is not available, use a triangular bandage and a stick or rod. − A blood pressure cuff can also be used. Control of External Bleeding • Tourniquet (cont’d) − Take the following precautions: • Do not apply over a joint. • Use the widest bandage possible. • Never use material that could cut into the skin. • If possible, use wide padding under the tourniquet. Control of External Bleeding • Tourniquet (cont’d) − Take the following precautions (cont’d): • Never cover with a bandage. • Inform the hospital. • Do not loosen after it is applied. Pain Control • May include: − Cold compress − Pressure dressing − Morphine sulfate or other pain medication Managing Wound Healing and Infection • Basic measures should be used in the prehospital setting. − Wounds that look infected or are not healing properly should be dressed and bandaged. − Pain control management may be indicated. Dressing Specific Anatomic Sites • Scalp dressings − Direct pressure is usually effective. − Determine the extent of injury. • Balance bleeding control needs against the possibility of causing further damage. • If skull has been damaged, apply pressure to areas around the break. Dressing Specific Anatomic Sites • Facial dressings − Reassure patient. − Direct pressure is effective to control bleeding. − If avulsed tissue is present, attempt to place it as close to its previous position as possible. − Assess for airway compromise. Dressing Specific Anatomic Sites • Ear or mastoid dressings − Do not place a dressing in the ear canal. − Use gauze sponges to aid in stopping blood loss. − Do not try to directly stop blood flow from the ear canal. • Place a bulky dressing over the external ear. Dressing Specific Anatomic Sites • Neck dressings − Minor injuries can become major. − Use occlusive dressings. − Make sure dressings do not interfere with blood flow or movement of air through the trachea. © E. M. Singletary, MD. Used with permission Dressing Specific Anatomic Sites • Truncal dressings − Cover open wounds with occlusive dressing, taping only three sides. − Assess breath sounds. − Use medical tape to secure dressing. Dressing Specific Anatomic Sites • Groin and hip dressings − Combined with direct pressure − Genitalia injuries should be managed by someone of the same gender. − Remain professional, and protect the patient’s privacy. Dressing Specific Anatomic Sites • Hand, wrist, and finger dressings − Place the hand in a position of function. − The hand and wrist can be splinted. − Leave fingers exposed. Dressing Specific Anatomic Sites • Elbow and knee dressings − Movement may cause dressings to shift. • For larger wounds, immobilize joint. − Assess distal neurovascular status. Dressing Specific Anatomic Sites • Ankle and foot dressings − Control bleeding with direct pressure. • If bleeding is arterial and not controlled, consider a tourniquet proximal to injury. − Always assess distal neurovascular function before and after caring for a wound. Abrasions • Superficial wound − Occurs when part of epidermis is lost from being rubbed or scraped over a rough surface Abrasions • Assessment and management − Oozes small amounts of blood − May be painful and prone to infection − Do not clean in the field. − Cover lightly with sterile dressing. Lacerations • Cut from a sharp instrument that produces a clean or jagged incision − Can injure structures beneath skin Courtesy of Rhonda Beck Lacerations • Assessment and management − Seriousness depends on: • Depth • Structures damaged − First priority is to control bleeding. Puncture Wounds • Caused by a stab from a pointed object − Can result in injury to underlying tissues and organs Puncture Wounds • Assessment and management − Consider potential depth of wound. − Treatment is similar to other wounds: • Look for entrance and exit wounds. • Take steps to prevent infection. Puncture Wounds • Assessment and management (cont’d) − Air may be injected under the skin with certain puncture wounds. • Monitor for edema. • Treat swelling with ice. Puncture Wounds • Assessment and management (cont’d) − If the object is still embedded in the wound: • Immobilize the object. • Transport the patient. © Custom Medical Stock Photo Puncture Wounds • Assessment and management (cont’d) − Basic management points for impaled objects: • Do not try to remove an impaled object. • Use direct compression, but not on the impaled object or adjacent tissues. • Do not try to shorten the object. • Stabilize the object with bulky dressing, and immobilize the extremity. Puncture Wounds • Assessment and management (cont’d) − Prehospital care goal—limit movement as soon as possible. − Secure the object as best as possible. • Provide reassurance. • Constantly assess for risks to life. Puncture Wounds • Assessment and management (cont’d) − Removal of impaled object may be necessary: • If object directly interferes with airway control • If object interferes with chest compression • If patient is impaled on an immovable object Avulsions • Occurs when a flap of skin is partially or completely torn loose − Amount of bleeding is dependent on the depth of injury. Avulsions • Assessment and management − Principle danger is loss of blood supply to the avulsed skin flap. − If wound is contaminated, provide irrigation. − Gently fold and align the skin flap back as close to its normal position as possible. • Cover it with a dry, sterile compression dressing. Avulsions • Assessment and management (cont’d) − Ice packs on the surrounding area may: • Decrease pain and swelling • Increase the length of time the underlying tissue remains viable − If patient is unstable, do not delay transport. Amputations • An avulsion involving the complete loss of a body part © E. M. Singletary, MD. Used with permission. Amputations • Assessment and management − Be aware of sharp bone protrusions. − The body part may be completely detached or soft tissues may remain attached. − Degloving injury: unraveling of skin from the hand Amputations • Assessment and management (cont’d) − If a body part is completed amputated, try to preserve it in optimal condition. • Rinse off any debris. • Wrap it loosely in saline-moistened sterile gauze. • Seal it in a plastic bag; place it in a cool container. • Never warm it or place it in water. • Never place it directly on ice or use dry ice. Amputations • Assessment and management (cont’d) − Transport as soon as possible. − If the amputated part is a limb or part of one, notify ED staff of: • Type of amputation • Estimated arrival time Bite Wounds © Chuck Stewart, MD − Cat and dog mouths are contaminated with virulent bacteria. Courtesy of Moose Jaw Police Service • Animals bites can be serious. Bite Wounds • Human bites usually occur on the hand. − Human mouths contain a wide variety of virulent pathogens. Bite Wounds • Assessment and management − Place a sterile dressing and transport promptly. − Splint an arm or leg if it is injured. − Determine and document: • When the bite occurred • Type of animal • What led to the biting incident Bite Wounds • Assessment and management (cont’d) − Rabies is a major concern with dog bites. • Once signs appear, it is almost always fatal. • Spread by bites or licking an open wound • Can be prevented by a series of vaccine injections − Do not enter until the scene is secured. Bite Wounds • Assessment and management (cont’d) − Emergency treatment for human bites includes: • Control all bleeding and apply a sterile dressing. • Immobilize the area with splint or bandage. • Provide transport. Crush Syndrome • Can develop if a body area is trapped for longer than 4 hours and arterial blood flow is compromised − If muscles are crushed beyond repair, tissue necrosis leads to rhabdomyolysis. Crush Syndrome • Freeing the body part from entrapment may result in release of harmful products. − “Smiling death” may occur. − Other significant complications include: • Renal failure • Life-threatening dysrhythmias Crush Syndrome • Assessment and management − Scene safety is the first consideration. − Complete primary assessment as possible. − Obtain IV access before removing the object. − Infuse normal saline. − Add sodium bicarbonate as part of the IV fluid. Crush Syndrome • Assessment and management (cont’d) − If pretreatment not possible, apply a tourniquet. • Will reduce some of the reperfusion damage − Treat severe hyperkalemia with 25 mL of D50W, followed by 10 units of regular IV insulin. − Rapidly transport once the patient is freed. Crush Syndrome • Assessment and management (cont’d) − Manage other injuries once en route. • Handle open injuries with dressing and bandages. • Splint fractures. • Prepare to administer fluids as needed. • Take vital signs every 5 minutes at minimum. • Get an ECG reading to detect dysrhythmias. Crush Syndrome • Assessment and management (cont’d) − When transporting, consult with medical control about using a hyperbaric chamber. Compartment Syndrome • Develops when edema and swelling cause increased pressure within a closed softtissue compartment − Leads to compromised circulation − Commonly develops in extremities − Can cause tissue necrosis Compartment Syndrome • Assessment and management − Presents with six Ps: • Pain • Paresthesia • Paresis • Pressure • Passive stretch pain • Pulselessness Compartment Syndrome • Assessment and management (cont’d) − Many signs may be delayed or nonspecific. − Can cause death of local tissues − Risk of sepsis − In-hospital intervention includes fasciotomy. High-Pressure Injection Injuries • Occurs when a foreign material is forcefully injected into soft tissue, causing: − Acute and chronic inflammation − Damage from: • Direct insult • Chemical inflammation • Ischemia from compressed blood vessels • Secondary infection High-Pressure Injection Injuries • Assessment and management − Question patient about nature of injury. − Inspect injury for extent of visibly damaged tissue. − Palpate affected area for signs of edema. − Check for crepitus at injury site. High-Pressure Injection Injuries • Assessment and management (cont’d) − Gently irrigate open wounds with normal saline. − Dress and bandage open injuries. − Manage pain if necessary. − Injury may require emergent surgery. Facial and Neck Injuries • May involve airway or large blood vessels − Airway compromise may arise. • Suctioning and positioning may be necessary. − Open injuries to the jugular or carotid vessels can result in exsanguinations. Facial and Neck Injuries • Assessment and management − Assess airway patency, protection, and oxygen. − May require more invasive management: • Endotracheal tube • A Combitube • Laryngeal mask airway Facial and Neck Injuries • Assessment and management (cont’d) − Bleeding control can be started while airway control is underway. • If only one EMS provider is available, address bleeding after airway is secured. Thoracic Injuries • May appear minor but produce deadly internal damage • Determine MOI during primary assessment to detect life threats. Thoracic Injuries • Assessment and management − Four steps to assessment: • Inspection • Palpation • Auscultation • Percussion Abdominal Injuries • Range from minor abrasions to evisceration • Inspect abdomen and palpate area. • During inspiration, the size of thoracic and abdominal cavities change. − Increases risk of drawing air into pleural space Abdominal Injuries • Assessment and management − Focus on injury to underlying organs and blood vessels. • Could quickly lead to serious complications Summary • The skin fulfills crucial roles, including maintaining homeostasis, protecting tissue, and regulating temperature. • The skin’s main layers are the epidermis and dermis. • The layer beneath the dermis is the subcutaneous layer. Below that is the deep fascia. Summary • Tension lines are patterns of tautness in the skin. If a wound is parallel to skin tension, it may remain closed, while a wound that runs perpendicular may remain open. • Soft-tissue injuries are seldom the most serious injuries, although they may look dramatic. • In a closed wound, soft tissues beneath the skin are damaged but the skin is not broken. Summary • In an open wound, the skin is broken, and the wound can become infected and result in serious blood loss. • In a crush injury, a body part is crushed between two solid objects, causing damage to soft tissues and bone. • Cessation of bleeding is the first stage of wound healing. • Inflammation is the second stage of healing. Summary • Factors that affect wound healing include the amount of movement the part is subjected to, medications, and medical conditions. • Infection signs include redness, pus, warmth, edema, and local discomfort. • Observe scene safety first. Then assess the ABCs. Summary • During the history intake, ask about the event causing the injury. Ask about the patient’s last tetanus booster, and if they are taking mediations that may affect hemostasis. • Complete the physical exam either en route or at the scene, depending on mechanism of injury. • Document scene findings. Summary • Be empathetic. • Controlling bleeding is a part of soft-tissue injury management. Follow the ICES mnemonic for closed injuries. • When managing open wounds, control bleeding and keep wound clean by irrigating and sterile dressings. • Dressings and bandages cover wounds, control bleeding, and limit motion. Summary • Medical tape may secure a bandage in place. Dressings should not be applied too tightly. • Bleeding control methods include direct pressure, elevation, immobilization, and tourniquets. • Dressing and bandaging techniques vary for different areas of the body. Summary • Avulsion management includes irrigation; gently folding the flap back onto the wound; and applying a dry, sterile compression dressing. • Do not remove impaled objects. • Animal and human bites can cause serious infection. Dogs and cats can carry rabies. • Crush syndrome may develop after a body part has been trapped more than 4 hours. Summary • Patients trapped for prolonged periods of time must be managed before being freed to improve survival chances. • Compartment syndrome results from pressure increase in a closed soft-tissue compartment. Presentation includes some or all of the six Ps. • Blasts can result in soft-tissue injuries. Use the DCAP-BTLS guideline for assessment. Summary • High-pressure injection injuries involve foreign material injection into soft tissue. • Special attention should be paid to softtissue injuries of the face, neck, thorax, and abdomen because they contain vital structures. Credits • Chapter opener: © Mark C. Ide • Backgrounds: Orange—© Keith Brofsky/Photodisc/ Getty Images; Blue—Jones & Bartlett Learning. Courtesy of MIEMSS; Purple—Jones & Bartlett Learning. Courtesy of MIEMSS; Green—Courtesy of Rhonda Beck. • Unless otherwise indicated, all photographs and illustrations are under copyright of Jones & Bartlett Learning, courtesy of Maryland Institute for Emergency Medical Services Systems, or have been provided by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.