Childhood Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome - Pediatrics

advertisement

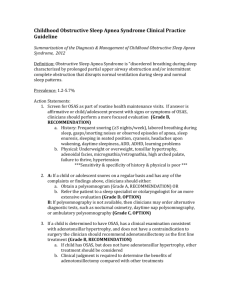

Childhood Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome New Recommendations For Diagnosis and Management By Dr. MAHMOUD HUSSEIN INTRODUCTION Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome ( OSAS) is a common condition in childhood and can result in severe complications if left untreated. OSAS occurs in children of all ages, from neonates to adolescents. However, it is most common in preschool-aged children, which is the age when the tonsils and the adenoids are the largest in relation to the underlying airway size In August 27, 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics ( AAP) published a practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of uncomplicated childhood OSAS . DEFINITION OSAS in children is defined as a “disorder of breathing during sleep characterized by prolonged partial upper airway obstruction and/or intermittent complete obstruction (obstructive apnea) that disrupts normal ventilation during sleep and normal sleep patterns. Prevalence rates of OSAS range from 1.2% to 5.7% worldwide. in children , the symptoms of OSAS are often subtle and do not exhibit uniquely specific features that would make such symptoms immediately recognizable. Conditions Associated With OSAS in Children Adenotonsillar hypertrophy Obesity Allergic Rhinitis, Asthma Sickle cell disease, Micrognathia,Down syndrome Craniofacial syndromes (Treacher- Collins, midfacial hypoplasia, Crouzon syndrome, Apert syndrome, Pierre Robin sequence, etc Achondroplasia, Mucopolysaccharidoses, Macroglossia Myelomeningocele Neuromuscular disorders (Duchenne muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, etc) Cleft palate repair and velopharyngeal flap Foreign body, Cerebral palsy Vascular hemangioma and other tumors Nasoseptal obstruction, Prematurity Pathophysiology Disordered breathing during sleep is a hallmark of OSAS. Breathing abnormalities include apnea and hypopnea The ability to maintain upper airway patency during the normal respiratory cycle is the result of a delicate equilibrium between the forces that promote airway closure and dilation. The 4 major predisposing factors for upper airway obstruction are the following: -Anatomic narrowing -Abnormal mechanical linkage between airway dilating muscles and airway walls -Muscle weakness -Abnormal neural regulation Recurrent episodes of upper airway obstruction typical of OSAS will result in intermittent hypoxia, hypercapnia, and significant swings of intrathoracic pressures, all of which may lead to disturbances in autonomic function. autonomic dysfunction are one of major underlying processes ultimately leading to sustained increases in vasomotor tone in patient s with OSAS, leading to systemic hypertension. Symptoms and Signs of OSAS History Frequent snoring ( ≥3 nights/wk) Labored breathing during sleep Gasps/snorting noises/observed episodes of apnea Sleep enuresis (especially secondary enuresis) Sleeping in a seated position or with the neck hyperextended Cyanosis Headaches on awakening Daytime sleepiness Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder Learning problems Physical examination: Underweight or overweight Tonsillar hypertrophy Adenoidal facies Micrognathia/retrognathia High-arched palate Failure to thrive Hypertension complications Morbidities can generally be divided into the 4 following immediate consequences of upper airway obstruction during sleep: •Sleep fragmentation •Increased work of breathing •Alveolar hypoventilation •Intermittent hypoxemia A. Cardiovascular Complications • Right heart strain • Reduced right ventricular ejection fraction • Right ventricular hypertrophy • Leftward shift of the interventricular septum • Cor Pulmonale • Systemic hypertension B. Growth poor growth and failure to thrive. Post treatment, sleeping energy expenditure decreased and weight increased. Treatment of OSAS results in increases in weight and height, even in children who were initially obese. C. Cognitive and Behavioural The AAP Subcommitee on OSAS pooled 6 cross-sectional studies that examined the cognitive and behavioural abnormalities in childhood OSAS. Abnormalities include - decreased school performance, inattention, excessive daytime sleepiness, aggression, hyperactivity and ADHD. - Young children who snore loudly and frequently are at higher risk for having lower grades in school several years after the snoring has resolved. These findings suggest that the adverse neurocognitive outcome and diminished academic performance in sleep disordered breathing may be only partially reversible, - particularly when the sleep disordered breathing occurs during critical phases of brain growth and development. Differential Diagnoses 1.simple snoring, usually not accompanied by oxygen desaturation, hypercapnia, or sleep disruption. Overnight polysomnography can be performed to differentiate 2.Daytime somnolence: Chaotic sleep schedules with inconsistent bedtimes and rise times , Narcolepsy. 3.Chronic Fatigue Syndrome 4.Congenital Stridor 5.Nocturnal Gastroesophageal Reflux 6.Sleep Disorder: Night Terrors, Nightmares Effeective strategies for evaluation of OSAS 1. history 2.physical examination 3.testing: - polysomnography - Apnea Hypopnea Index - Daytime Nap Studies - Overnight Oximetry - Anteroposterior and Lateral Neck Radiography - Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone and Thyroxine - Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) Polysomnography Polysomnography remains the criterion standard for establishing the diagnosis of (OSA) in infants, children, and adults. Ideally, polysomnography should be performed overnight and during the patient's usual bedtime. Polysomnography is necessary to document obstructive sleep apnea and gauge its severity. A history of snoring alone is not adequate for making a diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea or for determining its seriousness. Polysomnography provides the following measures: •Sleep state (≥2 EEG leads) •Electrooculogram (right and left) •Submental electromyelogram (EMG) •Airflow at nose and mouth (thermistor, capnography, or mask and pneumotachygraph) •Chest and abdominal wall motion (impedance or inductance plethysmography) •Electrocardiogram (preferably with R-R interval derivation technology) •Pulse oximetry (including a pulse waveform channel) •End-tidal carbon dioxide (sidestream or mainstream infrared sensor) •Video camera monitor with sound montage (analog or digital) •Transcutaneous oxygen and carbon dioxide tensions (in infants and children < 8 y) Apnea Hypopnea Index polysomnographic-derived index known as the apnea hypopnea index (AHI). The AHI is the total number of apneas and hypopneas that occur divided by the total duration of sleep in hours. An AHI of 1 or less is considered to be normal by pediatric standards. An AHI of 1-5 is very mildly increased, 5-10 is mildly increased, 10-20 is moderately increased, and greater than 20 is severely abnormal. Daytime Nap Studies Daytime nap studies are specific, but not sensitive, in detecting sleep apnea. This is because obstructive events are more likely to occur during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep than during other sleep stages, and very little (if any) REM sleep occurs during daytime naps in noninfants. Therefore, children with symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea who have normal nap study findings must undergo nocturnal polysomnography to exclude the diagnosis. Sleep studies should be performed without sedation Overnight Oximetry Unattended home overnight oximetry has been proposed as a screening study. However, it may miss the child with significant obstructive sleep apnea who does not have marked episodes of oxygen desaturation. Overnight pulse oximetry by itself is not adequate for establishing the diagnosis or excluding obstructive sleep apnea in children because it provides no information concerning sleep staging/sleep fragmentation or carbon dioxide. Anteroposterior and Lateral Neck Radiography: Neck radiography for soft tissue detail help define upper airway anatomy and adenoid size and exclude the possibility of rare nasal pharyngeal neoplasms. Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone and Thyroxine: Thyroid function studies are useful to exclude hypothyroidism, which is associated with tongue enlargement, weight gain, and obstructive sleep apnea. Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) If the clinical history suggests the possibility of narcolepsy, the MSLT should be ordered in conjunction with overnight polysomnography. MRI of the Brain and Brainstem A history of severe snoring, headaches, neck pain, urinary frequency, or swallowing problems raises the suspicion of Chiari malformation. Chiari malformations may occur in otherwise normal children and in association with congenital myelomeningocele. If brainstem dysfunction is suspected, MRI is necessary. Cranial CT imaging is not adequate to assess for brainstem and upper cervical cord lesions. Workup The AAP clinical practice guideline focuses on uncomplicated childhood OSAS associated with adenotonsillar hypertrophy or obesity in otherwise healthy children in the primary care setting. The AAP subcommittee was composed of pediatricians and experts in sleep medicine, pulmonology, otolaryngology, and epidemiology; and liaison members from the AAP Section on Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, the American Thoracic Society, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, the American College of Chest Physicians, and the National Sleep Foundation. Study Synopsis and Perspective As part of a routine health maintenance visit, clinicians should determine whether a pediatric patient snores, new guidelines advise. If he or she does snore or presents with symptoms of OSAS, a more focused evaluation is in order. These are among the recommendations included in updated evidencebased guidelines for the diagnosis and management of childhood OSAS. "Asking about snoring at each health maintenance visit [as well as at other appropriate times, such as when evaluating for tonsillitis] is a sensitive, albeit nonspecific, screening measure that is quick and easy to perform Study Highlights The investigators identified 350 articles from a literature search of relevant studies from 1999 to 2010. Exclusion criteria were reviews, case reports, letters to the editor, abstracts, non–English-language studies; animal studies; and studies of participants younger than 1 year, with central apnea or hypoventilation syndromes, or with OSAS related to other medical disorders. The investigators devised 8 key recommendations. Recommendation #1 At routine healthcare maintenance visits, clinicians should ask whether children snore. If children do snore or have signs or symptoms of OSAS, then a more focused evaluation is warranted. Screening for snoring is sensitive but nonspecific. Recommendation #2A Children who snore regularly and have any OSAS signs and symptoms should undergo polysomnography or, alternatively, be referred to a sleep specialist or to an otolaryngologist. The gold standard is overnight, attended, in-laboratory polysomnography. Specific pediatric criteria should be used. Polysomnography identifies the presence and severity of OSAS. Specialists might be able to diagnose and determine the severity of OSAS. Recommendation #2B If polysomnography is not available, alternative diagnostic tests include nocturnal video recording, nocturnal oximetry, daytime nap polysomnography, or ambulatory polysomnography. Alternative tests vs polysomnography have weaker positive and negative predictive values Recommendation #3 The first-line treatment of children with OSAS, adenotonsillar hypertrophy, and no contraindication to surgery is adenotonsillectomy. Adenoidectomy or tonsillectomy alone may be insufficient. The rate of serious complications is low. Research is needed to identify which obese children are most likely to benefit from adenotonsillectomy. The benefits and risks associated with adenotonsillectomy are preferable compared vs those of other treatment options. Recommendation #4 High-risk patients undergoing adenotonsillectomy should be monitored in the hospital postoperatively. Risk factors for postoperative respiratory complications are age younger than 3 years, severe OSAS by polysomnography, cardiac complications of OSAS, failure to thrive, obesity, craniofacial anomalies, neuromuscular disorders, and current respiratory tract infection. Recommendation #5 Patients should be reassessed for OSAS signs and symptoms after therapy to determine if further treatment is needed. The usual recommended time for re-evaluation is 6 to 8 weeks after treatment. Persistent symptoms should be assessed by objective testing or by a sleep specialist. Recommendation #5B High-risk patients, including those with significantly abnormal baseline polysomnogram results, sequelae of OSAS, obesity, or symptoms of OSAS, should be reassessed for persistent OSAS after adenotonsillectomy by objective testing or by a sleep specialist. A large proportion of high-risk children have persistent OSAS postoperatively. Recommendation #6 Patients should be referred for CPAP management if OSAS signs or symptoms or objective evidence persists after adenotonsillectomy or if adenotonsillectomy is not performed. CPAP is the most effective treatment of persistent postoperative OSAS. Alternative treatment is needed if adherence is suboptimal, even after behavioral modification methods are used. Recommendation #7 In addition to other treatment, weight loss is recommended in children with OSAS who are overweight or obese. Weight loss relieves OSAS, but it is a slow and unreliable method. Recommendation #8 Intranasal corticosteroids may relieve mild OSAS if adenotonsillectomy is contraindicated or if mild postoperative OSAS is present. Mild OSAS is defined as an apnea-hypopnea index of less than 5 per hour. Response should be measured objectively after approximately 6 weeks. Patients should be observed for recurrence of OSAS and adverse effects of corticosteroids. Treatment Adenotonsillectomy: Adenotonsillectomy, along with weight normalization, is considered the first line of therapy in children and adolescents with obstructive sleep apnea. Dietary restrictions: if obesity complicates obstructive apnea Positive-Pressure Ventilation Oral Appliances :assist in bringing the lower jaw and tongue forward during sleep, thus improving obstructive sleep apnea. These devices are expensive, require special dental expertise, and are associated with frequent adverse effects such as jaw pain and temporal mandibular joint dysfunction. Small growing children are likely to outgrow appliances, necessitating refitting and replacement. Nasal Fluticasone: administered daily for 6 weeks is shown to ameliorate the frequency of obstructive events in children with mild-to-moderate obstructive sleep apnea due to tonsil or adenoid hypertrophy by about one half. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty successful in relieving obstructive sleep apnea only if the major site of obstruction is localized to the soft palate Tongue Reduction Clinical Implications Updated guidelines by the AAP recommend that all children be screened for snoring. The recommended diagnostic test for OSAS in children who snore and who have signs or symptoms of OSAS is polysomnography. The first-line treatment of childhood OSAS is adenotonsillectomy for children with adenotonsillar hypertrophy. Other treatments include CPAP if adenotonsillectomy is not performed or if persistent postoperative OSAS is present, weight loss for overweight or obese children, and intranasal corticosteroids for mild OSAS if adenotonsillectomy is contraindicated or if mild postoperative OSAS is present.