Perceptions of Public Officials and Citizens of the

advertisement

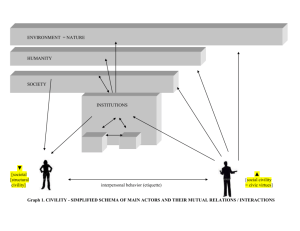

Perceptions of Public Officials and Citizens of the Public Decision-Making Process in the Midwest United States Jeff Ehrlich,Ed.D Assistant Professor, Health Care Leadership, Associate Dean of Hauptmann School for Public Affairs Park University 911 Main, Suite 915 Kansas City, Missouri, United States, 64105 Jeff.ehrlich@park.edu Becky Stuteville,Ph.D Assistant Professor, Director of Masters of Public Affairs, Hauptmann School for Public Affairs Park University 911 Main, Suite 915 Kansas City, Missouri, United States, 64105 Rebekkah.stuteville@park.edu 1 2 Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Who attends public meetings? ................................................................................................................. 8 Review of the Literature ............................................................................................................................. 10 Why do people attend public meetings? ................................................................................................ 10 How should public meeting and the public participation process be designed? ................................... 13 How should conflict be dealt with? ........................................................................................................ 16 How do you define civility? ..................................................................................................................... 19 Methodology............................................................................................................................................... 20 Citizen Responses ................................................................................................................................... 20 Public Officials ......................................................................................................................................... 21 Why do people attend public meetings? ................................................................................................ 21 Fearful ..................................................................................................................................................... 22 Anger ....................................................................................................................................................... 23 Passion .................................................................................................................................................... 23 Frustration .............................................................................................................................................. 24 Self-Interest............................................................................................................................................. 26 How should meetings be designed? ........................................................................................................... 27 Design...................................................................................................................................................... 27 Conflict .................................................................................................................................................... 28 How do you define civility? ..................................................................................................................... 29 Limitations and Delimitations ..................................................................................................................... 31 Conclusion ................................................................................................................................................... 31 References: ................................................................................................................................................. 34 3 Abstract Citizen participation in governmental decision-making is often regarded as an essential feature of democracy in the United States. The importance of citizen engagement in public and civic life is grounded in the United States’ heritage; yet the process which the public and decision-making officials encounter is often less than democratic. This research explored the responses of appointed public officials and compared the responses to those held by community members who attend publically held meeting and forums. The overarching research question asks: Does an opportunity exist for the general public and public officials to work collaboratively in an authentic effort of public discourse in the United States? Using data collected via focus groups with citizens and personal interviews with public officials, the study sought to identify what common ground exists between the expectations between the various public groups and officials. Three primary themes emerged from the focus groups and public official interviews; structure, procedure, and civility. 4 Introduction Citizen participation in government decision-making is often regarded as an essential feature of democracy in the American political system. The importance of citizen engagement in American civic life is grounded in the country’s heritage, beginning with the Puritans’ democratic tradition and later finding expression in the ideas of Thomas Jefferson (Cooper, Bryer, and Meek 2006; Kathi and Cooper 2005). This ideal of meaningful citizen involvement in a democracy, however, has not always translated into practice. In the United States, authentic citizen involvement has been limited by the system of representative democracy and the “ethos” of American administration (Kathi and Cooper 2005). America’s Founding Fathers intentionally designed a system that would temper the will of the masses by utilizing a system of representation as opposed to direct democracy. Kathi and Cooper (2005) argue that “though democracy requires some degree of citizen participation in governance, in a representative democracy, participation is an elusive ideal” (560). The principles of representative democracy continue to define the parameters of citizen participation in the United States even after the emergence of more direct forms of democracy such as the initiative and referendum. Citizen participation in governmental decision-making in the United States was further complicated by the professionalization of public administration in the 20 th 5 Century (Cooper, Bryer and Meek 2006). The 19th Century and early 20th Century ushered in Progressive reforms which created “barriers against the influence of citizenry on the day-to-day administration of government” (Cooper, Bryer, and Meek 2006, 77). The public administrator was placed at the center of the decision-making and policy implementation (Kathi and Cooper 2005) while citizens were relegated to the periphery. This relationship persisted throughout the 20th Century, and into the early 21st Century. As recently as 2007, Yang and Callahan argued that “meaningful, authentic participation is rarely found, as many public officials are reluctant to include citizens in decision making, or if they do, they typically involve citizens after the issues have been framed and decisions have been made” (249). The system of representative democracy and culture of administrative professionalism continue in the United States, but the relationship between public administrators and citizens is being reconsidered. According to Vigoda (2002), the interaction between public administrators and citizens has progressed along an evolutionary continuum. The most recent transition in this evolution is from the perspective that citizens are customers that require responsiveness from public administrators to the notion that citizens are partners who collaborate with public administrators (Vigoda 2002). The idea that citizens and government/public administrators are partners who must collaborate (Vigoda 2002) parallels the governance movement in public administration. Governance is a vague term that has multiple meanings (Meehan 2003; Rhodes 2001, and Sloat 2002), but governance often involves sharing public power, new arrangements for making and implementing policy away from the center, and 6 increased reliance on partnerships and networks (Meehan 2003). The term “governance ‘refers to collective problem-solving in the public realm rather than to the relevant agents of the political associations involved’” (Caporaso 1996, 32, quoted in Sloat 2002). The tension among the constitutional structure in the United States, the culture of professionalism in public administration, and the recent emphasis on collaboration and governance has implications for the relationship between public administrators and citizens. If governance calls for “’collective problem-solving in the public realm’” (Capoaso 1996, 32, quoted in Sloat 2001), then the current state of citizen participation may provide insight into the obstacles and opportunities for more collaborative problemsolving with citizens in the future. This paper will examine the perspectives that citizens and public administrators have regarding the public participation process at the local level. The study will utilize data collected by Consensus Kansas City, a consulting group, with input from 17 focus group sessions in western Missouri and eastern Kansas, and interviews conducted with four public administrators in the same region to evaluate citizen and public administrator responses to four questions: 1) Why do people attend public meetings, 2) How should public meetings and the public participations process be designed, 3) How should conflict be dealt with, and 4) How do you define civility? The responses by citizens and public administrators to these four questions will be compared to determine if there are commonalities and differences in their perceptions of citizens’ motivations to attend meetings, concerns with the substance and process of political participation, the nature of conflict, and the meaning of civility. 7 By cataloging and comparing the responses of these two groups, this study will examine the challenges and possibilities for redefining the relationships between public administrators and citizens in the 21st Century. However, before addressing the four key questions, the paper will first examine who attends public meetings. Who attends public meetings? The success of public deliberation relies on those interested in the issue or problem. Engagement in the discussion is an opportunity for those who wish to either be heard or to simply monitor and absorb the discussions. This wide range of opportunities for Unites States citizens to participate in the deliberation is perhaps rooted in New England town meetings that is centuries old. However, questions arise on whether this similar town meeting remains a legitimate form of debate and deliberation when a relatively small number of those registered to vote participate in the process (Williamson and Fung, 2004). Some question the efficacy of public meetings if the numbers of those who engage in the process are relatively small. Bryan (1999) argues that given the time and additional resources that many find as a hurdle to participation, roughly 20% of the population registered to vote in the United States. Getting citizens to attend public meetings is a significant accomplishment. The New York Times reported that as fewer people attend public meetings, those who are professionally interested and those who are vocal advocates tend to dominate the proceedings, creating a “hostile atmosphere” (1996). Even with the Times article, Bryan posits that there is almost no connection between a public meeting’s aggregate socioeconomic measures and town meeting attendance. Bryan also states that if any bias does exist with those who attend those 8 who are considered middle-class in socioeconomic indicators attend public meetings in substantial numbers over the ultra-rich or the disadvantaged. Those who observe public meetings note that this venue does not draw a significant representation subsection of the public. As a result, attendance at public meetings is dominated by public officials, those who represent special interest groups, and others with a significant stake in the agenda of the public meeting (Poisner, 1996). It is noted that most of those in attendance do not speak, but merely listen to the proceedings. Because of the lack of general participation, often the impression taken away from a public meeting may not represent the views of the general public. Jansen and Kies (2005) maintain that citizens’ motivation to attend and participate is dependent on assumed political impact. This impact is absent if public official participation is limited or non-existent. Shoul and Rabinowitz (2011) claim there are five community actions conditions to encourage collaborative work in order to work towards a collective result. These include: 1. Community norms and policies that encourage collaborative behavior 2. Mutually trusting relationships between different people and points of views 3. Community networks and a web of organizational and individual relationships that is inter-connective 4. Widespread use of community problem-solving process 5. Leadership made up of respected community members Shoul and Rabinowitz’s premise that community norms and actions may substantiate McComas, Besley, and Black’s (2010) research related to public meeting 9 rituals. The authors state; “People may lose faith in the process and cease to participate if they believe their participation is limited through the strategic manipulation of rituals” (127). The act of ritualization and recognizing culture may have significant impact on participation of the general public. Deficiencies in the amount and quality of education of the general public also influence attendance. There appears to be a lack of educational opportunities related to roles and responsibilities provided to citizens by local government and educational opportunities towards civic responsibilities. However, demand for these kinds of educational programs appear to exist (Lachapelle and Shanahan, (2008) While focus on attendance and who attends public meetings, it is safe to say that public administrators also bear some of the burden of the number of participants. Poorly run public meetings have a profound influence over attendees returning to future meetings (Lachapelle and Shanahan, (2008).. Public administrators must also make clear what the intent of the meeting is. If there is an expert presenting information, the clarity and simplicity of explaining the information make the process of public meetings such that those in attendance will be more responsive to those leading the meeting. When public citizens are confronted with experts who fail to explain or fulfill their role, they have the right to challenge the experts. The lack of responding to the citizen public in a manner of respect, knowledge and understanding may lead to apathy and ultimately, low attendance at public meetings. Review of the Literature Why do people attend public meetings? 10 Why people attend public meetings is arguably linked to the question of why people participate in politics in general. This section of the paper will briefly examine why citizen participate in political acts. It will use McComas et. al’s (2006) three categories of research on “citizen participation in political activities” as a framework. In their evaluation of why citizens choose to attend or not to attend public meetings, McComas et al. (2006) explain that there are three basic categories of research on citizen participation in political activities. These categories include: 1) “Rational incentives,” 2) “Socioeconomic Status and Mobilization Incentives,” and 3) “Relational Incentives” (674-678). The first category of research on citizen participation is based on “rational incentives” (McComas et. al. 2006, 674). They contend that there are practical or rational reasons why people attend meetings. For example, people may indicate that they attend meetings because they are curious or they want to provide input to public officials. McComas et al. include Adams’s (2004) research on the functions of public meetings in this category of rational incentives. Adams (2004) argues that public meetings are not effective mechanisms for promoting deliberation or rational persuasion. They can, however, help citizens achieve other political objectives such as providing information to officials, showing support for or criticizing public officials, and communicating with other citizens. McComas et al. (2006) also believe that it is likely that citizens weigh the costs of attendance against the benefits, and there is less incentive to attend meetings when the costs outweigh the benefits. Finally, they argue that the timing of the meeting is also a rational consideration. A citizen’s motivation to attend a meeting may be affected by 11 how early or late a meeting is scheduled in the decision-making process. The second category, “Socioeconomic Status and Mobilization Incentives” is represented by the work of Sidney Verba and his collaborators (McComas et. al. 2006). This category of research highlights socioeconomic status and political efficacy. McComas et. al. explain that “in general, this research has found that people most likely to participate are those who have the greatest capacity to participate because of levels of education and relevant political experience, and those who believe they can make a difference (Almond & Verba, 1989; Rosenstone & Hansen, 1993; Verba, Schlozman, & Brandy, 1995)” (McComas et. al. 2006, 676). As early as the late 1960s’ Verba examined the problems of democratic participation. Verba (1967) argued that the likelihood that anyone will participate in politics is related to their resources, motivation, and the social structure and culture (Verba 1967). His evaluation of what motivates people to participate in general may be relevant to discovering why people attend public meetings. Verba (1967) examined at three different aspects of motivation: 1. “Does the individual believe in the effectiveness of political participation?” Those who have not experienced successful participation are not likely to believe that they will be effective. 2. “Does the individual have specific interests for which he considers governmental activity relevant?” People are more likely to attempt to participate if they believe that governmental activity is relevant to their needs. 12 3. “Is political participation directly satisfying?” In addition to achieving a particular goal through participation, individuals may also find participation to be satisfying “in and of itself” or it may be socially satisfying. (Verba 1967, 64). In other words, Verba’s work suggests that people will be motivated to participate if they believe that they will be effective based upon past success, if they believe that the governmental activity is relevant their own needs, or if they find participation itself to be satisfying. The final category of research is on “relational incentives.” This body of research explains “participation based on citizens’ experiences with authorities and their decisionmaking procedures” (McComas et. al. 2004, 677). It looks at the effects that citizens’ perceptions of procedural fairness can have on their satisfaction with the process and outcomes. These three bodies of research indicate that there may be many reasons why citizens decide to participate in political activities. Citizens may participate for practical reasons such as curiosity or the desire to criticize public officials. Citizens may also make a “rational” calculation of whether the benefits of participation outweigh the costs before deciding to engage. The efficacy literature suggests that citizens participate because they believe that they may be effective, the government activity is relevant to them, or they simply find the process to be satisfying. Finally, the procedural justice research implies that participation may be affected by whether or not citizens perceive the process to be fair. How should public meeting and the public participation process be designed? 13 Although the literature on the design of public meetings is somewhat limited, the research on citizen participation does offer some recommendations for designing public meetings and the public participation process. For example, Crosby et. al. (1986) outline six criteria for citizen participation processes. First, the participants must be representative of the broader community and they should be selected by a method that is not manipulated by special interests or elected officials. Second, the hearing process should be structured in a manner that allows the average citizen to do an effective job at decision making. This means that citizens must be provided with accurate information, and given sufficient time to reflect on the information. Additionally, the agenda should be well planned, the group leader must facilitate, and participant views must be adequately recognized. Third, the procedures should be fair. Crosby et. al. (1986) concedes that there are no “perfect solutions” to some of the problems involved in ensuring fairness. For example, it is difficult to balance the desire to give everyone an equal opportunity to speak with the desire to run an efficient meeting. They conclude that “some combination of staff input, advocacy presentation, and an open agenda must be used in order to organize the information efficiently for decision making while at the same time being fair to the parties involved” (Crosby et al. 1986, 172). Fourth, the citizen participation process should be cost effective. The authors assert that if one form of citizen participation is significantly more expensive than another, the cost must be justified. Fifth, the method of participation should be “adaptable to a number of different tasks and settings” (Crosby et. al. 1986, 172). Finally, the recommendations made by the citizens who participate in the process should be given serious attention by public officials. 14 Similar recommendations have been made by Lukensmeyer and Boyd (2004). They offer seven principles of effective citizen engagement. Their principles were largely derived from the authors’ experience organizing large “21Century Town Meetings” for AmericaSpeaks, but they contend that they can be applied to “projects of various sizes, contexts, and approaches” (Lukensmeyer and Boyd 2004, 11). These principles are: 1) “Develop context-specific strategies” (11). The issues to be considered should be “ripe,” the project should be linked to other decision-making processes that are taking place, and there should be reason to believe that decision-makers will consider citizen input. 2) “Build credibility with citizens and decision makers” (11-12). Citizen engagement efforts should have diverse participation and should include community leaders. A reputable organization should serve as the “neutral broker” for the process. Additionally, the process should include a realistic assessment of trade-offs. 3) “Ensure diverse participation” (12-13). The process should engage those who are not already actively involved in the community and should expand beyond those who have “an axe to grind.” 4) “Establish informed dialogue” (13). Participants should be given detailed background information that is balanced and neutral. Professional facilitators and issue experts should be utilized. 5) “Create a safe public space” (13-14). A “safe” environment that encourages citizens to share their thoughts can be facilitated by arranging the tables and chairs closely together, ensuring that services are handicapped accessible, 15 providing adequate staff to respond to participant questions, and giving participants the opportunity to provide anonymous feedback, when appropriate. 6) “Influence decision making” (14). A combination of strategies can help citizen engagement processes to have more influence on decision makers. 7) “Sustain citizen commitment” (14-15). Inform citizens about how their input was used, solicit their participation on ongoing committees, or invite them to join an implementation team, if appropriate. Finally, King et. al. (1998) offer several practical suggestions for overcoming barriers to authentic participation. In general, they suggest that we “change the way we meet and interact with each other and with citizens. Specifically, they recommend having “many small meetings; roundtable discussions; outside facilitators; equal participants” and no one being privileged due to position, status, or other characteristics (King et al. 1998, 324).” There are several common themes that run through the literature on designing public meetings and the public participation process. The commonalities include the representative participation by members of the community, accurate information for citizens regarding the issues, the use of facilitators to assist with the process, physical arrangements (eg. tables and chairs) that invite participation, and serious consideration of the recommendations by public officials. These criteria, as well as others noted above, contribute to the design of effective public meetings and citizen participation processes. How should conflict be dealt with? 16 The role of conflict in groups has been a matter of debate among public administration and management theorists since the early 20th Century. Views about the nature and utility of conflict fall along a continuum of two extremes--those that argue that conflict should be avoided and those that contend that conflict should be embraced. The predominant view in the early 20th Century was that conflict is dysfunctional. Robbins and Judge (2009) explain that “the traditional view of conflict was consistent with the attitudes that prevailed about group behavior in the 1930s and 1940s. Conflict was seen as a dysfunctional outcome resulting from poor communication, a lack of openness and trust between people, and the failure of managers to be responsive to the needs and aspirations of their employees” (485). This perspective was shared by theorists such as Elton Mayo who argued that conflict should be avoided (Fry and Raadschelders, 2008). One notable exception to this early trend was Mary Parker Follett’s work on social conflict. Unlike her contemporaries, Follett saw social conflict as “neither good nor bad, but simply inevitable” (Fry and Raadschelders 2008, 113). Her message was that “healthy solutions” to conflict are possible (Fox, 1968, 524). Follett’s approach to conflict was echoed in the human relations view which dominated from the late 1940’s to the mid-1970’s (Robbins and Judge, 2008). Like Follett, this school of thought argued that conflict was natural, inevitable, and potentially beneficial. More recently, the interactionist view of conflict has emerged. According to this approach, conflict should not only be accepted, it should be encouraged. The premise is that managers in organizations should encourage constructive conflict in order to keep the group innovative, self-critical, and creative (Robbins and Judge 2008). 17 In addition to these three views on the nature of conflict, there are also a variety of conflict management techniques. Conflict resolution techniques include problem solving, creating shared goals, expanding resources, avoidance, smoothing, compromise and using formal authority to promote a resolution (Robbins and Judge 2008 citing Robbins 1974). Conversely, there are also conflict-stimulating techniques such as bringing in people with diverse backgrounds and designating a devil’s advocate (Robbins and Judge 2008).1 These various views and techniques have been used by theorists and practitioners to explain, describe, and manage conflict in the workplace and in other social groups. It is acknowledged, however, that public meetings differ from other organizational settings in some fundamental ways. For example, a person may work for an organization for many years, while a public meeting may last for only a matter of hours. The limited duration of relationships in public meetings can alter the incentive for resolving conflict in a meaningful and healthy way. On the other hand, the manner in which conflict is viewed, as either harmful or beneficial, can change the manner in which conflict is perceived and utilized in any setting. If conflict is perceived as unhealthy, techniques may be used to avoid conflict in the workplace or in a public meeting. On the other hand, if conflict is viewed as healthy, then techniques may be employed to welcome different viewpoints, encourage conflict, and seek creative solutions. In other words, the various perspectives on conflict and conflict management techniques used in other organizational settings may also be relevant to public meetings. 1 Not all of the Robbins and Judges (2008) conflict management techniques have been listed. Techniques such as training and organizational restructuring were not included. 18 How do you define civility? Perhaps civility could be considered the quality of the public deliberation and those involved. Civility breeds opportunities for both the citizen and the public official. Lack of civility in public meetings may bring a well-meaning meeting to a disturbing end. Civility is about more than merely being polite, although being polite is an excellent start. Civility fosters a deep self-awareness, even as it is characterized by true respect for others. Civility requires the hard work of staying present even with those with whom we have deep-rooted and perhaps fierce disagreements. It is about constantly being open to hear, to learn, to teach and to change. It seeks common ground as a beginning point for dialogue when differences occur, while at the same time recognizes that differences are enriching. It is patience, grace, and strength of character Institute for Civility in Government (2012). Public meetings in the United States are designed in theory that offers a large range of opportunities to participate with one another as well as public officials regarding public problems and policies. While mentioned previously in this paper, the concept that with fewer people attending public meetings, those with professional interests and vocal activists eventually create a hostile atmosphere (Williiamson and Fung, 2004). Rogers (2011) points out that the approach people take to discussion and debate is characterized by an attitude that public meetings can become a dialog of "I disagree with you - and not only that, but you're a bum and I'm going to yell so loud I can't hear what you're saying." 19 Defining the principle of civility is difficult. As a foundation for democracy and civil discussions, civility urges public officials and the citizen public to set a high standard for civil discourse as an example for others in resolving differences constructively and without disparagement of others Rogers (2011). The lack of this form of civic engagement is assumed to result in a democratic deficit (Rose and Saebo,2010). Certain types of civility behavior lead to poor consequences. McComas, Besley, and Black (2010) note that while some participants in the meeting may perform as part of the ritualistic behavior often found in public meetings, may also provoke criticism and less than desirable outcomes. Costa (2002) states that one can understand the frustrations and anger when attending public meetings, but the only thing that will get everyone through the process is the ability to respectfully listen and then respond. This lack of civility may lead others to avoid or ignore public meetings because of the poor behavior of other citizens and public officials. Methodology Citizen Responses Archived focus group data was coded for themes. In all, 17 focus groups conducted by Consensus KC, a consulting firm who conduct public forums related to the deliberative process was used for the citizen viewpoint. Patton (2002) states that archived data can prove to be a valuable asset not only with what is learned directly, but also the stimulus for paths of inquiry. This data was a stimulus for us to ask similar probing questions of public officials who regularly engage in public forums. 20 The data from Consensus KC represent a wide range of citizen opinion. After reviewing the data and coding in a consistent qualitative method, four major themes emerged. These include: 1) why people attend public meetings; 2) dealing with conflict (in public meetings); 3) the design of public forums or meetings 4) defining civility. This archived data was valuable in that the focus groups were from a diverse cross-section of attendees. These included various age groups, male and female responses, educational levels, and differing political views and beliefs. Public Officials In order to gain another perspective on citizen participation and public meetings, four city officials were interviewed. These included three city managers and one recently retired city manager. The interviews consisted of two female and two males. All were interviewed in their offices or place of their choice. Following Patton’s (2002) definition of the standardized open interview, questions were worded and asked that maintained consistency with each city official. This approach requires fully wording each question before the interview. Since the questions were open-ended, the official was welcome to elaborate or add further comments. Since coding and the emerging themes of the focus groups were done prior to these interviews, questions similar to the themes were asked. Why do people attend public meetings? Twenty-two percent of the focus groups participants indicated that they attend public meetings for emotional reasons. The most frequently noted emotions were fear, anger, passion, and frustration. 21 Fearful When asking why citizens attended public meetings 32% of those that indicated emotional reasons said that they were fearful of what may be decided or acted upon. One respondent noted it was “Fear. If fear is involved, it motivates you to get involved, to engage and protect your interest. Another citizen stated “I worked at a hospital as a health professional. When I would see people fear they won't get their food stamps, you want to advocate for them.” One group member noted; “there are lots of things to fight for, (in public meetings) and if I think it will affect my ability to have enough money to live here, I'm going to get in there and fight for it.” Action also motivated another person. “Fear is one of the strongest motivators and can drive a lot of action.” A public official noted this when asked why citizens attend public meetings. “From our perspective, our residents rarely attend a public meeting and so when they do attend. . . it’s because they are very upset. So they attend to voice their concern about what it is that’s going on. The problem with that is that you always have, we have a problem getting out the “silent majority.” We only hear from the people who are being negative about something. People are still coming to public hearings because they feel very strongly one way or the other about something. But I found that people came on both sides of the issue to the hearings.” Another official stated; “they come for a lot of reasons. It’s often about entertainment, fascination, and the reactions of others. They want to feel a part of what is going on. I’ve also seen times when (the public) want to be obstinate and object to everything. Almost to be mean.” 22 Anger Anger also called citizens to action in public meetings. Thirty two percent of the responses related to emotions also mentioned anger as a strong reason to attend public meetings. “It would be more an anger issue with me. I’m not going to the city council meeting and congratulate someone”. Yet another participant noted; “Anger is the emotion that will drive me there or maybe curiosity. Things like financial or education or health care, employment or definitely immigration issues. I think if I knew something that might be of help from personal experience that I would speak. If I knew I could tell them how I feel. If I hear about it I would attend. It’s about frustration or anger.” One person posited: “For the first three years I was angry and thought these people were stupid and ignorant and I couldn’t even stand to talk to them. Then I decided the anger was only hurting me.” When a city manager was asked about conflict in public meetings, he had this to say. “I think you establish guidelines early; establish these from the beginning. It’s important to take control early. When you give everyone time to speak is almost like releasing a pressure valve. It all begins with self-discipline. The (public) group will police themselves.” A comment from another city official noted; “I see times where they (public) wear their religion and emotion on their sleeve. It’s a lot to do with recognizing the issues for conflict early and communicating. Also, do what they (public) understand and sometimes simplify the issues” Passion 23 Passion was also an important issue. Twenty percent of those responding that they attended public meetings for emotional reasons mentioned passion as a reason to attend. Passion had different meanings to various focus group participants. One mention of passion was the reason why citizens become involved. Another is related to the passion that comes forth in public meetings. A focus group respondent noted; “if the meeting is designed well and the purpose is communicated –with clarity around purpose of meeting and structure allows people to be passionate, acknowledge that they are being heard.” Another said; “these kinds of meetings have a place for emotion or passion. It shouldn’t be that it can’t be there. Some of the greatest moments in history have come in those moments of passion.” One more mention of passion was noted; “When you question and dig deeper into a person’s passion you can understand where they’re coming from and can better appreciate where they’re coming from.” A public official noted that passion is an issue. Even administrators….I think they have emotions and ideas and they should. It’s part of the passion….part of what you are…it is part of what make you….I mean you are not robots…nobody likes to see robots ….nobody wants to hear robots speak they want hear somebody that has emotion, the reason why they like something sometimes it just boils down to values. Sometimes, though you have to stay stoic and if you are just passionate about something you just need to be neutral. I don’t think there is anything necessarily wrong with the people getting a little angry; by that I mean to show that they have passion.” Frustration 24 When attending public meetings as a citizen, frustration was a felt emotion that was reported. Sixteen percent of those responding that they attended public meetings for emotional reasons mentioned frustration as a reason to attend. “Remember the meeting on strategic plan when there was trouble with the neighborhood. For neighbors to make it adamantly clear they didn’t want a school building in detriment to the neighborhood: frustration drove them to come.” Another similar comment states “But I feel impacted by things and don’t go – there is some kind of tipping point. Maybe for me it is frustration – the lack of progress on issues. We seem to be continuously talking and not moving forward; I don’t feel there is a lot of honesty in the public process.” The focus group interviews often blurred together with respondents voicing their opinion related to frustration and anger intermingling with one another. As an example, one person noted that; “there is a lot of anger and frustration is one of the biggest factors. When there’s a public meeting, there’s a lot of us versus them feeling, like “what are they going to do to us now?” One person noted; “I think if I knew something that might be of help from personal experience then I would speak. If I knew, I could tell them how I feel. If I hear about it I would attend. It’s about frustration or anger.” A city manager with over 30 years’ experience noted that he had a different level of frustration than the public who attend these meetings. When asked what frustrated him in public meetings, he stated; “Nothing, really. I enjoyed these meetings more than I found frustration. It’s the Democratic process. I try to recognize the frustrating issues from a public perspective before the meeting and get a good feel for public reaction. He goes on to state; “It’s difficult when those attending these meetings have a partial understanding of the issues.” “I want to go faster, but the process (public meetings) 25 takes time and process. Sometimes it feels like an inability to persuade. Like, ‘why don’t they understand?’ But along with that, they (the public) are unique and we can’t think the same way through the process.” Self-Interest In addition to citing emotional reasons for participation such as fear, anger, passion and frustration, self-interest was a comment made by 16% of those in the focus groups as it relates to attending public meetings. “I’m trying to get more involved in politics, and as a (potential) politician I might go for that reason.” Another typical comment read; “People who show up at these things are motivated by the way the issue is framed. If you can frame it in terms of money in their pocket, they’ll show up. If you can hit them in terms of core emotional issues, they’ll show up.” One respondent stated his feelings this way; “Self-interest – when an issue will affect you or your family.” Another idea was stated in a way that addressed a larger issue of re-zoning in this person’s community. “A lot of people turned out, even those who weren’t affected personally because if you do this to these folks what will you do to us?” In addition, a respondent mentioned; “It would have to affect me financially, whether it be a tax issue or a property issue or a family issue, something that has to do with one of those three factors. It has to have a major impact on my life in order for me to get involved. Family means like education, especially with younger kids. I went to my first board of education meeting about a local school spending issue.” A city official made this remark about self-interest in public meetings. “You’re really a part of that, you are a relevant thing, I mean you’re just, all of a sudden you go 26 to work the next day, somebody says something about it and you say…oh yeah, I was there….I know about that…..you know….you just become relevant. Everybody wants….it’s human nature, everybody wants to be a part of something. One administrator noted; “One week virtually you have a council meeting and no one shows up; you have a budget hearing and all kinds of people show up. Most of the time it is a personal interest that they have that brings them to a public meeting.. A similar comment made by official states; “A lot of times we will see citizens attend meetings when it involves primarily their neighborhoods.” How should meetings be designed? The questions regarding meeting design and conflict were combined since structure, procedures, and ground rules are subthemes that permeated much of the focus group discussion on both design and conflict. Design When asked about meeting design, 10% of the respondents mentioned that ground rules should be established. One focus groups participant stated that “Whoever is in charge of the meeting needs to be in charge of the meeting. That’s a skill not everyone has. Just because you are a public official doesn’t mean you know how to hold a meeting.” “The people behind the ideas are afraid of the audience.” “Roberts rules – there’s time and a place for that.” “Having rules – mutual understanding about how we’re going to behave tonight.” Another participant had this to say about meeting structure; “the environment that events occur in. If you have people who are making 27 decisions behind wooden barrier that says something. If you want conversation, set up room different. Change that dynamic.” With regard to the room structure, one respondent stated, “I like small tables. It invites everyone in. You can look directly at the person. When everyone is sitting but one person standing, it can be intimidating. If you’re in the back, it’s hard to hear or see how they’re feeling about an issue.” When the same question was asked of a city manager, the response was; “I like to give them a note card and a pen when they come in so that as they come up with questions, they can write them down so they haven’t forgotten them when it’s time to ask questions. That seems to help people to not interrupt during a presentation. I think you establish the ground rules in the beginning.” Conflict When the focus groups discussed conflict in public meetings, structure, procedures and ground rules were often intertwined with the responses. Twenty percent of the respondents mentioned the need for structured meetings, procedures and ground rules when asked how conflict should be dealt with. Some comments centered around city officials and the meeting design. “Is it set up for people to have a discussion or for just a one-way thing? School board meetings don’t have a chance to be civil because it’s set up for confrontation… Usually starts with official making a speech and then saying I’m sure you have a question. Their staffers have arranged to call on certain people. There isn’t a chance to have a real dialogue.” Interestingly, a respondent stated; “We tend to be a little more civil here in the chicken fried Midwest. I saw on TV, town hall meetings when legislators would go home and all we saw was them being yelled 28 at.” “In our meetings, the person who was in charge would start off by saying; we’re going to have a civil discussion, ‘don’t talk too long, if you do I’ll cut you off.’ Set the rules. When someone announces the rules before you begin you have a better meeting.” When asked about dealing with conflict, a city official discussed various meeting structure ideas as well. “Each meeting has its own dynamic. It’s about recognizing the dynamic. Not too much structure and no absolutes.” One manager stated it this way; “You have to call and be on the agenda. That way we know what the issues are about. This way we can educate evenly.” Another thought was; “anticipate (the issue) and head it off.” Another interesting point was to break the public into small groups. “It’s the best way to come up with ideas and avoid conflict.” Another city administrator noted that “Well, the truth is that I think [conflict] has to be dealt with immediately. And I think that it has to be deal with strongly.” How do you define civility? As stated in the literature section, civility fosters a deep self-awareness, even as it is characterized by true respect for others Institute for Civility in Government (2012). Civility appears to be a major theme. Over 23% of those in the focus groups mentioned that civility means respect in some form. When the focus group was probed on what they expect civility to look like in public meetings they responded accordingly. “It’s hard to be civil. There will always be two sides.“ An opposing view states; “Being civil is listening well, looking people in the eye, smiling.” “Civility is about respect. Respect of everyone’s opinion.” “Approaching people in a non-threatening way. It’s treating other 29 people the way you would like to be treated in public.” “My liberal friends don’t go on the attack. But my religious right friends will go on the attack.” “I think civility is a part of the human condition, part of living together and interaction. It can happen at the national or local level. It’s how people strive to solve problems. Sometimes they behave uncivilly”. A young focus group member posited; “nobody should be allowed to dominate. Everybody should be heard. Adults don’t like to follow rules.” A corresponding comment made in another focus groups states; “younger people may not know the rules of how you should address someone, like saying Mr. Mayor. It can be taken as incivility. It can cause an undercurrent.” “Age has a lot to do with it. Tradition. People maybe expect things to be a certain way.” Another simple definition notes; “Everything we know about civility we learned in kindergarten.” One city official noted this about civility; “And it’s really getting…It used to be when I first came, my issue was civility. Trying to get them to be civil to each other. We have really instituted a lot of changes to better control people. And when they get to talk, and when they stand, and who they address, and who they are talking to. So as not to get in an argument.” Another comment related to civility from public officials noted; “It’s about mutual respect. It’s the Golden Rule. Both sides must give the due respect and appreciate all values. It gives a sense that there is no battle if everyone is respectful.” “Be respectful. Everyone is entitled to their opinion and thoughts. Treat each other with respect.” A conflicting thought read, “I am not sure how to get it. Sometimes I ask myself, “how did I get it last time?’ We become civil by self-educating.” 30 Limitations and Delimitations A delimitation of this study looked at response rates to questions that were 10% or greater. While other interesting data was presented to the researchers, the length and complexity and reporting of these data was not feasible for this research paper. A major limitation of the research was the number of responses from public officials. While some of the public official views were similar in thought, a few comments were unique such as one who noted there were few, if any frustrations with city meetings. Another noted some meetings took on an air of citizen fanaticism. Perhaps interviewing a greater number of public officials may lead to either supporting or refuting some of the observations. Conclusion While the majority of comments related to the perceptions of public officials and citizens of the decision-making process came from the focus groups, the addition of public officials and their thoughts added a dimension that in some cases agreed or refuted comments by the citizens. Both groups are interested in making the process one that leads to respectful and engaging dialog. Specific common ground and collaboration for both groups do exist, and ‘getting the cards on the table’ may be one step in either developing or continuing to cultivate an understanding between each group’s perceptions during public meeting process. Culture change in who attends public meetings and why citizens attend public meetings requires community members and city officials to adopt new ways of thinking and acting (Shoul and Rabinowitz, 2011). 31 This shift in cultural thinking and acting happens when the new culture becomes the norm and is simply how a community does as a matter of course. The data from this study demonstrate some interesting commonalities among the literature, focus groups participants’ views, and public officials’ perspectives. With regard to why people attend public meetings, Verba’s work appears to be the most relevant. Verba (1967) argued that people are more likely to participate if they think that government activity is relevant to their needs. Both the focus groups and public officials indicated that self-interest is a key reason why people attend public meetings. Additionally, the findings regarding how public meetings and the public participation process should be designed are relatively consistent among the literature, focus groups and public officials. The literature outlined several procedures and aspects of the physical environment that should be taken into consideration including the agenda, facilitators, small meetings, and roundtables. Likewise, the majority of respondents noted similar meeting design changes. This was as simple as time allotments (two minutes seemed to be the norm) of those who are discussing the issue, rearranging the meeting facility such as small groups, tables and chairs, dispose of physical barriers such as higher level seating and wooden barriers, and establishing certain rules prior to opening the session for comments. Additionally, the public officials alluded to specific ground rules when asked about meeting design. The data on conflict is somewhat inconclusive. The fact that 20% of the focus groups participants stated that structured meetings, procedures, and ground rules are needed indicates that they believe that conflict is somewhat inevitable, but should be 32 managed. On the other hand, the public officials’ views appear to be more in line with the traditional perspective that conflict is dysfunctional. Community debate and the deliberative process in the United States involving citizens and public officials date back to New England town meetings that are centuries old. One may argue that the same themes explored in this paper are no different than those faced by our founding fathers and the I republic of citizens. The three primary themes structure, procedure, and civility are issues each public forum must consider as consequential to productive public forums. Finally, as a key issue and a term found throughout the interviews, civility was one that almost all agreed with. The definition and comprehension of the term was quite simple; treat each other with respect. 33 References: Adams, Brian (2004) “Meetings and the Democratic Process”. Public Administration Review, 64 (1): 43-54. Bryan, F.M.(1999), “Direct Democracy and the Civic Competence: The Case of the Town Meeting.” In S.Elkin and K.E. Soltan(eds.), Citizen Competence and Democratic Institutions; Pennsylvania State University Press Costa, Peter, 2002. “Housing Plan Stirs Emotion.” Boston Globe, October 6. Cooper, Terry. Bryer, Thomas, Meek, Jack. (2006) “Citizen-Centered Collaborative Public Management." Public Administration Review, Special Issue, December 2006: 76-88. Crosby,Ned., Kelly, Janet,, Schafer, Paul (1986). Citizen Panels: A New Approach to Citizen Participation. Public Administration Review, 46 (2): 170-178. Fox, Elliot M. (1968) “Mary Parker Follett: the Enduring Contribution.” Public Administration Review, 28 (6): 520-529. Fry, Brian R. and Jos C.N. Raadschelders. (2008), Mastering Public Administration. 2ed. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. 34 Hill, Carolyn J. and Laurence E. Lynn Jr. (2009) Public Management: A ThreeDimensional Approach. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. Jansen, D and Kies, R. (2005) “Online forums and deliberative democracy.” Acta Politica 4093:317-335. Kathi, Pradeep Chandra and Terry L. Cooper. (2005) “Democratizing the Administrative State: Connecting Neighborhood Councils and City Agencies.” Public Administration Review 65 (5): 559-67. King, Cheryl Simrell, Kathryn M. Feltey, and Bridget O’Neill Susel.(???) The Question of Participation: Toward Authentic Public Participation in Public Administration. Public Administration Review, 58 (4): 317-326. Lukensmeyer, Carolyn and Ashley body. 2004. “Putting the ‘Public’ Back in Management: Seven Principles for Planning Meaningful Citizen Engagement.” Public Management. . Lachapelle, P.R. and Shanahan, E.A. (2008) “The Pedagogy of Citizen Participation in Local Government: Designing and Implementing Effective Board Training Programs for Municipalities and Counties.” Journal of Public Affairs Education 16(3): 401-419. 35 McComas, Katherine A., John C. Besley, and Craig W. Trumbo. (2006) “Why citizens Do and Do Not Attend Public Meetings about Local Cancer Cluster investigations.” The Policy Studies Journal, 34 (4): 671-698. McComas, Katherine A., John C. Besley, and Craig W. Trumbo, (2010) “The Rituals of Public Meetings.” Public Administration Review; Jan/Feb;7o(1): 122-130. Proquest. Meehan, Elizabeth. (2003)” From Government to Governance, Civic Participation and ‘New Politics’’ the Context of Potential Opportunities for the Better Representation of Women.” Occasional Paper No. 5. Center for Advancement of Women in Politics School of Politics and International Studies, Queen’s University Belfast. http://www.qub.ac.uk/cawp/research/meehan.pdf (Accessed 5/27/2010) Gross, M.B. (1996) “Political Poison at the Grass Roots”. New York Times, May 4, p 19. Patton, M.Q. (2002) Qualitative research & evaluative methods. Sage Publications. Poisner, J. A (1996) “Civic Republican Perspective on the National Environmental Policy Act’s Process for Citizen Participation.” Environmental Law; Spring 53-94. Putnam, R. (2000) Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster. 36 Rhodes, R.A.W. (1996) “The New Governance: Governing without Government.” Political Studies 44: 652-667. http://law.hku.hk/gl/rhodes.pdf (Accessed 12/29/11). Robbins, Stephen P. and Timothy A. Judge. (2009), Organizational Behavior. 13 ed. Pearson. Shoul, Mark and Rabinowitz, Philip. (2011) “Creating a New Kind of Community Organization to Mobilize the Politically Sidelined Majority Around the Issue of Building Civic Cultures of Collaboration.” National Civic Review, 36-47. doi: 10.1002/ncr.2257 Sloat, Amanda. (2002)” Governance: Contested Perceptions of Civic Participation.” Scottish Affairs 39. Verba, Sidney. (1967) “Democratic Participation.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 373, Social goals and Indicators for American Society , 2: 53-78. Vigoda, Eran. (2002) “Responsiveness to Collaboration: Governance, Citizens and the Next Generation of Public Administration. “ Public Administration Review 62(5) 527-540. 37 Williamson, Abby and Fung, Archon (2004) “Public Deliberation: Where Can We Go?” National Civic Review 3-15. Retrieved from Pro-Quest, 2012. Yang, Kaifeng and Kathe Callahan (2007) “Citizen Involvement Efforts and Bureaucratic Responsiveness: Participatory Values, Stakeholder Pressures, and Administrative Practicality.” Public Administration Review 67(2): 249-64. 38 39