The Productive Benefits of Playgroups- Social Capital

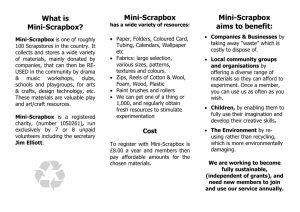

advertisement

Or as Humpty says:

"The question is," said Alice, "whether

you can make words mean so many

different things."

"The question is," said Humpty Dumpty,

"which is to be master - - that's all."

The structure of playgroups in Victoria

What is Social Capital?

What evidence do we have that playgroups

contribute to Social Capital?

Utilising the benefits of playgroups in the

early childhood setting

Continuum of Playgroups

Increasing level of family and service

support

Intensive

(agency-led)

Families move

between formats

according to need

Facilitated

(agency-led)

Community

Playgroups

(parent-led)

At the interface between

supported and intensive there

may be planned transitions

At the interface between

community and

supported there may be

occasional support

Outcomes

Nurturing children, supporting families, building

communities

Working for the day when all families with children under

school age:

have opportunities for social play and learning in their

communities; [ CHILD]

have positive social networks that support their

parenting; and [ PARENT ]

have opportunities for meaningful participation in

community life. [ COMMUNITY ]

CCCH Paper: Playgroups in Australia 2012

The commonalities of most definitions of social capital

are that they focus on social relations that have

productive benefits.

Social capital is about the value of social networks,

bonding similar people and bridging between diverse

people, with norms of reciprocity.

The Social Capital Research site

{http://www.socialcapitalresearch.com/definition.html}

Intuitively, then, the basic idea of “social capital” is that one’s

family, friends, and associates constitute an important asset,

one that can be called upon in a crisis, enjoyed for its own

sake, and/or leveraged for material gain. What is true for

individuals, moreover, also holds for groups. Those

communities endowed with a diverse stock of social networks

and civic associations will be in a stronger position to confront

poverty and vulnerability (Moser 1996; Narayan 1996), resolve

disputes (Schafft 1998; Varshney 1999), and/or take

advantage of new opportunities (Isham 1999). Conversely, the

absence of social ties can have an equally important impact.

Social Capital: Implications for Development Theory, Research, and Policy Final

version submitted to the World Bank Research Observer

To be published in Vol. 15(2), 2000

Social Capital

Group Characteristics

•

•

•

•

•

•

# memberships

Contribution of money

Frequency of participation

Participation in decision making

Membership heterogeneity

Source of group funding

Generalised Norms

•

•

•

Helpfulness of people

Trustworthiness of people

Fairness of people

Togetherness

•

•

How well people get along

Togetherness of people

Everyday Sociability

•

Everyday sociability

Neighbourhood Connections

•

•

Asking neighbour to help with a sick child

Asking neighbour to for yourself if sick

Volunteerism

•

•

•

•

•

Trust

•

Narayan and Cassidy 2001

Have you volunteered

Expectations of volunteering

Have you helped someone

Criticism of not volunteering

Fair contribution to neighbourhood

Trust of family, neighbourhood, other tribes, business,

government, service providers, justice organisations

Less social capital as vulnerability increases

Absence of benefits of

social capital

Continuum of Playgroups

Increasing level of family and service

support

Intensive

(agency-led)

Families move

between formats

according to need

Facilitated

(agency-led)

Community

Playgroups

(parent-led)

At the interface between

supported and intensive there

may be planned transitions

At the interface between

community and

supported there may be

occasional support

Social Capital: Community Playgroups

•

•

•

•

•

•

# memberships

Contribution of money

Frequency of participation

Participation in decision making

Membership heterogeneity

Source of group funding

Parent run and controlled, parents involved

in decision making through committee and

general involvement in playgroup activities.

A level of heterogeneity exists. Funded by

parents involved.

Generalised

Norms

•

•

•

Helpfulness of people

Trustworthiness of people

Fairness of people

Parents support each other, meet outside

of playgroup, assist with issues such as

PND. Families socialise. Shared

responsibility.

Togetherness

•

•

How well people get along

Togetherness of people

Playgroup parents operate as a friendship

group

Everyday

Sociability

•

Everyday sociability

Parents are involved in their community

and confident to participate in their

community

Neighbourhood

Connections

•

Asking neighbour to help with a

sick child

Asking neighbour to for yourself if

sick

Supports are obvious with parents

collectively parenting children and able to

assist each other

Volunteerism

•

•

•

•

•

Have you volunteered

Expectations of volunteering

Have you helped someone

Criticism of not volunteering

Fair contribution to neighbourhood

Purely volunteer based . Parents are

expected to participate as best they can in

the playgroup and encouraged to take on

decision making duties

Trust

•

Trust of family, neighbourhood,

other tribes, business,

government, service providers,

justice organisations

Group

Characteristics

•

20,000 families a week attending playgroup.

Trust is built within the group. Trust of

community

37% of parents learnt about good businesses in their

community through playgroup

49% learnt about toy libraries through playgroup

25% learnt about health services

92% rate their playgroup friendly

96% of parents agreed that attending playgroup has provided

them with a sense of friendship, community and/or

connectedness

95% said their child’s social skills benefit through interaction

with other children

67% said it gives their children opportunity for physical activity

58% said children benefit through learning to take turns and

share

Are the benefits of playgroups shared

evenly?

Do vulnerable families who do not attend

community playgroups get productive benefits

which build social capital?

How do we conceptualise the differences in

outcomes for families attending community

and supported playgroups?

Individualised

Community Wide

STRENGTHS

INTENSITY

PRESSURES

High

Pressure

High

Strength

Low

Strength

High

Pressure

Low

pressure

High

Strength

Low

Strength

Low

pressure

THE INTERPLAY OF COMMUNITIES:

The Differing Strategies For Empowerment

Low Strength

Low Pressure

Low Pressure

High Strength

High pressure

High Strength

Low Strength

High Pressure

UK Children in Need

Owen & Gill., The Missing Side of the Triangle

The Missing Side of the Triangle

A model for analysing the impact of community on parents and children

This model is based on the information and connections covered in The missing side of the triangle, by Gordon Jack and Owen Gill.

STRENGTHS

PARENTS

CHILDREN

1 Practical resources in the community

Employment (links to income

and social integration)

Good local shops (eg good

quality/value food)

Transport available (access

to employment and leisure

facilities)

Anti-poverty resources

(eg credit unions, welfare

rights advice)

Affordable local childcare

(access to employment for

parents)

Social network development

(eg drop-ins, community

centres)

Anti-poverty resources

(eg breakfast clubs, subsidised

holidays)

Good quality, accessible play

resources.

Specific resources for black,

other minority ethnic or dualheritage children, and children

with disabilities.

Social network development

(eg clubs, playgroups)

Local schools provide inclusive

and supportive environment.

PRESSURES

PARENTS

CHILDREN

High local levels of unemployment.

Inadequate local shops

(including rural accessibility)

Transport expensive, infrequent,

unreliable.

No access to financial advice or

services

Expensive credit facilities

Childcare resources inadequate

(opening hours, location, cost)

Leisure facilities, outings and

holidays not affordable or

accessible.

Lack of safe, local play

areas/facilities

Few organised clubs and outof-school activities.

No specific resources for black,

other minority ethnic or dualheritage children, or children

with disabilities

Local schools provide poor

educational and social

environment

(eg low achievement, bullying)

Culture of people

“keeping themselves to

themselves”

High rates of mobility into and out

of neighbourhood

Lack of links between wider family

networks and community networks

Lack of positive contact with

rang of people in community

Children’s networks disrupted

by high mobility of residents

Lack of links between school

and community networks

Parents see community as unsafe

(people safety, crime/drugs safety,

physical safety)

Harassment from neighbours

(including racial harassment)

Children perceive local

environment as threatening

(people, crime/drugs, physical

danger)

Harassment from local adults

and children (including racial

harassment)

Lack of established positive

community norms around childcare

practice and values

Children do not experience

stable and established

community norms

Negative sense of identity and

belonging conveyed to certain

children (eg teenagers, poor

children, black, other minority

ethnic and dual-heritage

children, children with

disabilities)

Lack of personal resources or

knowledge to access available

facilities

Personal demands too high to

develop reciprocal supportive

relationships

Alienates potential sources of

support

Networks produce demands rather

than support

Perception that facilities are not

accessible for their family

Experience of frequent house

moves including homeless

Lack of personal resources to

access available facilities,

networks and opportunities

Alienates other children/other

children bully or stigmatise

her/him

Family networks either very

limited or difficult

Child has had frequent moves

(including homeless)

Perceptions that facilities are

not accessible for her/him

High level of individual

‘environmental stress’ (eg poor

quality housing, unemployment,

lack of childcare)

Parents feel unsupported,

threatened, or frightened in their

community (mental health issues,

isolation)

Parents’ ambitions are to leave the

community.

Children feel threatened,

frightened, and unvalued in

their community.

Anxiety, depression, anti-social

behaviour, school

failure/exclusion.

2 Natural networks in the community

Reciprocal ‘helping’

relationships in community

Long term residence of

families

Non-threatening relations

with immediate neighbours

Balances community – mixed

age structure

Established and supportive

social networks

Good contact with immediate

neighbours

Positive contact with significant

adults from different generations

in community

Integration between school and

community networks

3 Child and family safety in the community

Established positive

community norms around

childcare practice and values

Children perceive their

immediate area to be safe, rather

than threatening (people, safety,

crime/drugs, safety, physical

safety)

4 Community norms around children and childcare

Established positive

community norms around

childcare practice and values

Children experience stable and

established community norms

Positive sense of identity and

belonging conveyed to all

children

5 The individual family and child in the community

Personal resources and

knowledge to access

available facilities

Personal resources to

develop and maintain

supportive networks

Perceptions that local

facilities are accessible for

their family

Developing confidence in using

available facilities and

opportunities

Developing confidence in local

networks with other children

Perception that facilities are

accessible to them (eg black,

other minority, ethnic or dualheritage children and children

with disabilities see facilities as

accessible)

6 Cumulative impact of all of the above

Low level of individual

environmental stress

Feel supported in the

community in their parental

role of bringing up children

Community is perceived as a

“good place to bring up

children”

Children feel their community is

a good place to be living

Children feel safe and valued in

their community

Development of positive identity,

self-esteem, and security

The full publication, incorporating research and practice examples, is available from Barnardo’s UK Childcare Publications

Individualised

Community Wide

STRENGTHS

INTENSITY

PRESSURES

Intensive

Playgroups

Transitional

Model

Supported/

Facilitated

Playgroups

Community Playgroups

Transitional

Model

Intensive

Playgroups

Supported

Playgroups

Limited

Transitional

Model

Community Playgroups

Transitional

Model

Intensive

Playgroups

Supported

Playgroups

Transitional Model

Community Playgroups

Recent research conducted by the Telethon Institute in

Western Australia demonstrated that for disadvantaged

families prolonged playgroup attendance is associated

with:

Better learning outcomes- particularly for boys

Better social-emotional outcomes particularly for girls

Mothers have greater and more consistent social support

More books in the home

Less TV

More participation in other activities

and that Prolonged attendance improves outcomes.

Children from disadvantaged families are less likely to

access playgroup services but participation is higher

than expected.

The evidence suggests that these are the children who

have the most to gain from attending with social and

learning outcomes significantly improving.

Parents benefit too with the study finding mothers from disadvantaged

families who went to playgroup were:

more likely to have consistently good support from friends over time

more likely to see improvements in the level of support they received from friends

over time

less likely to see declines in the level of support they received from friends over

time

The study found that children from disadvantaged families attending

playgroup also:

Have more books in the home

Watch less TV

Attend more activities outside the home (e.g. swimming pools, museums, movies,

cultural events)

Social Capital

Group Characteristics

•

•

•

•

•

•

# memberships

Contribution of money

Frequency of participation

Participation in decision making

Membership heterogeneity

Source of group funding

Generalised Norms

•

•

•

Helpfulness of people

Trustworthiness of people

Fairness of people

Togetherness

•

•

How well people get along

Togetherness of people

Everyday Sociability

•

Everyday sociability

Neighbourhood Connections

•

•

Asking neighbour to help with a sick child

Asking neighbour to for yourself if sick

Volunteerism

•

•

•

•

•

Trust

•

Narayan and Cassidy 2001

Have you volunteered

Expectations of volunteering

Have you helped someone

Criticism of not volunteering

Fair contribution to neighbourhood

Trust of family, neighbourhood, other tribes, business,

government, service providers, justice organisations

Less social capital as vulnerability increases

Absence of benefits of

social capital

Continuum of Playgroups

Increasing level of family and service

support

Intensive

(agency-led)

Families move

between formats

according to need

Facilitated

(agency-led)

Community

Playgroups

(parent-led)

At the interface between

supported and intensive there

may be planned transitions

At the interface between

community and

supported there may be

occasional support

Focusing solely on the most disadvantaged will not reduce

health inequalities sufficiently.

To reduce the steepness of the social gradient in health,

actions must be universal, but with a scale and intensity that

is proportionate to the level of disadvantage.

Individualised

Community Wide

High Social Capital already

exists

INTENSITY

Social Capital needs to be built

▫ INTENSITY

Vast

proportion

of families

can

participate

in

community

playgroups

and

organise

these

These families participate well in

kindergarten, child care and school

Smaller proportion of

families under significant

pressure find it difficult

to engage with

community based

playgroups and require

higher levels of

facilitation via intensive/

supported playgroups.

These groups should be

transitioned as their

strengths are built

How are you working with

your supported playgroups

to transition these families?

▫ INTENSITY of FACILITATION

Lowest 2-3%

Vast

proportion

of families

can

participate in

community

playgroups

and organise

these

Smaller proportion of

families under

significant pressure

find it difficult to

engage with

community based

playgroups and require

higher levels of

facilitation via

intensive/ supported

playgroups. These

groups should be

transitioned as their

strengths are built

There are a smaller

number of families

in this community

who can sustain

participation in a

community

playgroup and

these should be

encouraged.

Likely to get these

families participating

first in any initiative

The majority of families

in this community have

higher pressures than

strengths. These families

find it difficult to engage

with community

playgroups and require

more facilitated and

intensive engagement

strategies to harness &

maintain their

participation in

playgroups. These

playgroups are

supported or

therapeutic in nature.

How are you working with your

supported & intensive playgroups to

transition these families?

How are playgroups useful in the institutional/

formal early childhood setting

35% of parents attending playgroup also had

their children in childcare

46% of parents learnt about kindergarten ,

preschool and school through playgroup

27% of parents learnt about child care

through their playgroup

97% of parents agreed that attending

playgroup assisted their child’s development

Why playgroups are useful to child outcomes in

early childhood.

Children learn and grow in relationship with their parents:

Companionable Learning- Dr Roberts

Parents are children’s first and most enduring educatorsParents are engaged from the start in playgroups and

vulnerable parents learn to engage.

Parents have training in committees and decision making prior

to getting to child care, Kindergarten and school. They

participate.

Children are prepared and comfortable in groups of their peers

& the routine of learning environments.

For vulnerable children and families

Playgroups can make up the disparity of

disadvantage with prolonged attendance.

Parents can increase their trust in services such as

children's services and increase their participation.

The groundwork with literacy , learning and routine

is established in playgroup.

Good transition planning and relationships with

supported playgroups can maximise a vulnerable

families participation in children's services.

Co-Location

Transition Program- active regional planning

Regional versus metropolitan- the benefits of

a regional community

Active Engagement with the broader service

sector- primary health, housing, child and

family services.