Gender and educational and occupational choices

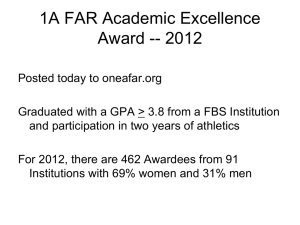

advertisement

Gender and Educational and Occupational Choices Jacquelynne S. Eccles University of Michigan Paper presented at the Gender Role Conference San Francisco April 2004 and Chinese University of Hong Kong, February, 2004 Acknowledgements: This research was funded by grants from NIMH, NSF, and NICHD to Eccles and by grants from NSF, Spencer Foundation and W.T. Grant to Eccles and Barber Why Do Women and Men Make Such Different Choices for Their Lives? In most cultures, women and men are concentrated in quite different occupations and roles. Why? My goal today is to provide one perspective on this quite complex question – a perspective grounded in Expectancy –Value Models of Achievement-related Choices Overview I began my research work in this area focused on one specific question: WHY ARE FEMALES LESS LIKELY TO GO INTO MATH AND PHYSICAL SCIENCE THAN MALES? Overview 2 I became increasingly aware, however, that this question is a subset of two much more general questions: WHY DOES ANYONE DO ANYTHING? WHAT PSYCHOLOGICAL, BIOLOGICAL, AND SOCIAL FORCES INFLUENCE THE CRITICAL CHOICES PEOPLE MAKE ABOUT HOW TO SPEND THEIR TIME AND THEIR LIVES? Goals Provide an overview of gender differences in occupational plans and choices Discuss alternative explanations for these differences – focusing on my Expectancy – Value Model of Achievement-Related Choices Summarize our research findings relevant to this question and this model Student responses to The Job Picture Story and Typical Day When I’m Thirty Essay NO. OF STUDENTS K-12 CAREERS 320 280 240 200 160 120 80 40 0 Females Males FEMALE A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O CAREER A 5% 95% B 14% 86% C 13% 87% D E 27% 32% 73% 68% F G H I J K L M N O 55% 48% 55% 61% 85% 98% 85% 87% 97% 42% 45% 52% 45% 39% 15% 2% 15% 13% 3% 58% N= 1987 A TRUCKDRIVER, CARPENTER, MECHANIC F DOCTOR, LAWYER, ARCHITECT, ACCT’NT K NURSE B PROFESSIONAL ATHLETE G ARTIST, ROCK STAR,SINGER, MUSICIAN L MODEL, DESIGNER, MOVIE STAR, DANCER C POLICE, FIREFIGHTER, MILITARY, PILOT H REPORTER, WRITER, TV ANNOUNCER M SECRETAR, FLIGHT, ATT. SALES CLERK D SCIENTIST. ENGINEER, COMPUTER SCI. I VETERINARIAN, FOREST RANGER, FARMER N UNPAID WORKER (HOMEMAKER, PARENT) E EXECUTIVE, BUSINESSPERSON, BANKER J TEACHER 0 THER MALE N=1962 TOTAL N= 3949 Participation in M/S/E careers In 1997, women represented * 23% of all scientists and engineers * 63% of psychologists * 42% of biologists * 10% of physicists/astronomers * 9% of engineers Source: National Science Foundation, 2000 Bachelor’s degrees in 2000 Percents Total M/S/E Physical Engineering Math/CS Earth Biological Social Psychology Women 28.0 0.8 1.7 2.2 0.2 6.5 8.6 8.0 Men 36.9 1.6 8.8 6.2 0.5 6.8 9.7 3.3 Source: NSF 02-327 Differences on Academic Indicators Females Earn Better School Marks than Males in All Subjects Areas at All Grade Levels Males Score Better than Females on Timed Standardized Tests Scores on Many Subject Areas Females are Now More Likely than Males to Pursue Many Forms of Advanced Education Males are More Likely than Females to be Placed in Remedial Educational Programs, to be Expelled from School, and to Drop Out of School Prematurely Common Explanations Biological Differences Brain differences – Hemispheric Specialization Specialized Sensitivities for Learning and Interests May be linked to verbal and spatial skills Such as preferences for speech input and faces versus mechnical objects Do not know the actual mechanisms but genetic studies suggest these may be heritable and may be sex-liked Disabilities Learning particular types of materials Social intelligence Anxieties Anxiety and Performance Performance Females Level Males Anxiety Common Explanations Hormonal Prenatal Linked to developing organizational structure of brain and other hormonal systems Postnatal Right after birth hormonal peaks Puberty Adulthood Activational systems Psychological Differences Ability Self Concepts for Different Skill Areas Domain Specific Interests and Preferences More General Differences in Values and Goals Anxieties Social Experiences Family and Peers Role Models Expectations Provision of Differential Experiences Schools and Larger Society Differential Treatment Differential Teaching Practices for Different Subject Areas Very Difficult to Distinguish These Hypotheses All are Likely Influences In Addition, People Self-Socialize into the Culturally Approved Social Roles and Niches One Way to Frame the Question Do these differences exist even amongst a group of individuals who have sufficient intelligence to choose even the most demanding intellectual careers? For example amongst people who are highly gifted in both the verbal and mathematical areas? Highest Graduate Degrees Obtained by 1945 Degree N Men Percent Women N Percent Master's (arts or 58 11% 76 18% science) Ph.D. (or comparable 60 11% 13 3% doctorate) Law 79 14% 3 <1% M.D. 47 8% 5 1% M.B.A. 19 3% 1 <1% Graduate engineering 14 2% 0 degree Graduate certificate 1 <1% 13 3% in librarianship Graduate diploma in 0 8 2% social work Other 5 1% 3 <1% -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Note: Percentages based on total number of college graduates. Data derived from Terman and Oden, 1947] Current Gifted Research Similar differences emerge Females now more likely to go on to college but are still underrepresented in the physical sciences and engineering Another View Look at the proportion of women at each step along the pipeline Figure 1 40 40 30 Percent Who are Females Percent Who are Females Proportion of Females in Each Group 20 10 0 30 20 10 0 Math-SAT Freshman BS Degrees over 550 planning to major Engineering PhD Degrees Math-SAT over 550 Freshm an planning to m ajor BS Degrees Physical Sciences PhD Degrees Final View Put the question into a larger perspective – Why does anyone do anything? Subjective Task Value 1. Interest Value – Enjoyment one gets from doing the activity itself 2. Similar to Intrinsic Value Utility Value – Relation of the activity to one’s short and long range goals Similar in some ways to Extrinsic Value Subjective Task Value Continued 3. Attainment Value: Extent to which engaging in the activity confirms an important component on one’s self-schema or increases the likelihood of obtaining a desired future self or avoiding an undesired future self. a. Individuals seek to confirm their possession of characteristics central to their self-schema. b. Various tasks provide differential opportunities for such confirmation. c. Individuals will place more value on those tasks that provide the opportunities for this confirmation. d. Individuals will be more likely to choice those activities that have high attainment value. Subjective Task Value Continued 4. Cost – Psychological Costs Fear of Success, Fear of Failure, Anxiety Financial Costs Lost Opportunities to Fulfill Other Goals or to do Other Activities Key Features of Model 1. Focuses on Choice not on Deficits 2. Points Out Importance of Studying the Origins of Individuals’ Perception of the Range of Possible Options 3. Focuses on the Fact that Choices are made from a Wide Range of Positive Options How Does This Relate To Gender? Personal Identities Personal Experiences Self Concepts Personal Values Success Expectations Personal Goals Subcultural Scripts, Beliefs, and Stereotypes Life Choices Social Identities Salience Content Societal Beliefs, Images, and Stereotypes Perception of Barriers And Benefits Due to One’s Group Membership Subjective Task Value Gender-Roles and Ability Self Concepts and Personal Expectations Cultural Stereotypes about Which Gender is Supposed to be Good at Which Skills Extensive Socialization Pressures to Make Sure These Stereotypes are Fulfilled Gender-Roles and Subjective Task Value 1. 2. Different Hierarchies of Core Personal Values a. Concern with Social Goals versus Concern with Power or Achievement Goals; b. Concern with Social Relationships versus concern with Individual Achievement and Status. c. Interest in Things versus Interest in People. d. Interest in Cooperation versus Interest in Competition Density of Hierarchy a. Single-mindedness versus Diverse Interests Gender-Roles and Subjective Task Value Continued 3. Different Long Range Goals 4. Different Definitions of Success in Various Goals and Roles. a. What does it take to be a successful father versus a successful mother? b. What does it take to be a successful professional? c. What does it take to be a successful human being? Gender Differences in Values Among Gifted Children and Youth 1. Activity Interests a. Females less interested than males in physics, chemistry b. Females more interested in English, foreign languages, music, drama, medical-related majors, and biological sciences c. Females more interested in reading, writing and domestic activities and arts and crafts d. Females less interested in sports, working with machines, tools, and electronic equipment Gender Differences in Values Among Gifted Children and Youth Continued 2. Personal Values a. Females score higher on social and aesthetic values b. Females score lower on theoretical, economic and political values 3. Density of Values a. Females tend to rate a broader range of activities and future roles as important than do males. b. Males are more likely to rate a few activities very high and the remaining activities very low. Michigan Study of Adolescent Life Transitions (MSALT) U of M Affiliated Investigators: Waves 1-4 Jacque Eccles Carol Midgley Allan Wigfield Jan Jacobs Connie Flanagan Harriet Feldlaufer David Reuman Doug MacIver Dave Klingel Doris Yee Christy Miller Buchanan Waves 5-8 Jacque Eccles Bonnie Barber Lisa Colarossi Deborah Jozefowicz Pam Frome Sarah Lord Mina Vida Robert Roeser Laurie Meschke OVERVIEW OF DESIGN AND SAMPLE: MICHIGAN STUDY OF ADOLESCENT LIFE TRANSITIONS – MSALT DESIGN: On-going Longitudinal Study of One Birth Cohort Data Collected in Grades 6, 7, 10, 12; and again at Ages 20 and 25 Data Collected from Adolescents, Parents, and School – Most Using Survey Forms SAMPLE: Nine School Districts Approximately 1,200 Adolescents Approximately 90% White Approximately 51% Female Working/Middle Class Background Michigan Study of Adolescent/Adult Life Transitions: MSALT Time 1 Time 2 YEAR Fall 1983 Spring Fall 1984 1984 GRADE 6th 6th 7th WAVE 1 2 3 YOUTH SURVEY PARENTS SURVEY TEACHER QUESTIONNAIR E RECORD DATA FACE TO FACE INTERVIEW SPRIN 1988 G 1985 7th 10th 1990 1992 1996 2000 12th 6 years after H.S. 8 9 years after H.S. 4 5 6 2 years after H.S. 7 Time 3 9 + MSALT Sample General Characteristics School based sample drawn from 10 school districts in the small city communities surrounding Detroit. Predominantly White, working and middle class families Approximately 50% of sample of youth went on to some form of tertiary education Downsizing of automobile industry caused major economic problems while the youth were in secondary school BELIEFS AND GENDERED STEREOTYPES ABOUT MATH-RELATED PROFESSIONS PERCEPTIONS OF SOCIALIZERS ATTITUDES AND EXPECTATIONS GOALS AND GENERAL SELF-SCHEMATA 1. Personal Identity 2. Gender Role Identity 3. Career and Other Life Goals/Values 4. Minimum Standards for Achievement PERCEPTION OF TASK VALUE 1. Liking of math 2. Perceived usefulness of math 3. 4. GENDERED STEREOTYPES ABOUT MATH SKILLS APPROPRIATENESS SELF-CONCEPT OF MATH ABILITY Importance of doing well in math 1. Worth of the amount of effort needed to do well Enroll in advanced courses 2. Aspire to mathrelated careers EXPECTANCIES INTERPRETATION OF PAST MATH EVENTS PERCEPTIONS OF THE DIFFICULTY OF MATH ACHIEVEMENT BEHVAIOR 1. Current 2. Future Two Basic Questions ARE THERE GENDER DIFFERENCES ON THESE SELF-RELATED BELIEFS? DO THE GENDER DIFFERENCES IN THESE SELF-RELATED BELIEFS MEDIATE THE GENDER DIFFERENCES IN INVOVLEMENT? BUT FIRST, ARE THERE GENDER DIFFERENCES IN LONG TERM OCCUPATIONAL PLANS? Gender Differences in Ability Self Concepts – 7th Grade 6 5.5 5 Girls Boys 4.5 4 3.5 3 Math English Sports Gender Differences in Subjective Task Value – 7th Grade 6.5 6 5.5 5 Girls Boys 4.5 4 3.5 3 Math English Sports How Young Do These Differences Emerge Childhood and Beyond Study Similar Measures Similar Population in Southeastern Michigan 4 Middle Class School Districts Primarily White 3 Cohorts Beginning in 1st, 2nd, and 4th grades Followed Longitudinally until age 22 Gender Differences in Ability Self-Concepts: 1st, 2nd, & 4th Graders Mean Ratings 7 Girls Boys 6 5 4 General Throw Sports Tumble Music Ability Self-Concepts Read Math WORRY ABOUT PERFOMANCE ACROSS DOMAINS Mean Rating for Worry 5.5 5.0 4.5 4.0 Girls Boys 3.5 3.0 2.5 Math Reading Sports Domain Not be liked Hurt oth. Feel. Mean Rating of Importance IMPORTANCE OF ABILITY IN DIFFERENT DOMAINS 6.5 6.0 5.5 Girls Boys 5.0 4.5 4.0 Math Reading Sports Domain Music Social Enjoyment of Different Domains Mean Rating for Liking 6.5 6 5.5 Girls Boys 5 4.5 4 Math Reading Sports Domain Music Conclusion Gender Differences Occur across Several Domains for Both Ability Self Concepts and Subjective Task Values Gender Differences Emerge Quite Young Do These Differences Mediate Gender Differences in Course Taking and Activity Involvement? Predicting Number of Honors Math Classes (sex, DAT) N = 223 (honors students) Gender .15 Number of Honors Math Courses (R² = .08) .22 Math Aptitude Predicting Number of Honors Math Classes N = 223 (honors students) Self-Concept of Ability in Math .15 Gender (R² = .06) .12 .14 .18 Number of Honors Math Courses Interest in Math (R² = .19) (R² = .02) .13 .25 Math Aptitude .14 Utility of Math (R² = .04) Predicting # of Physical Science Classes (sex, DAT) Gender .16 Number of Physical Science Courses .34 Math Aptitude (R2 = .15) Predicting # of Physics Classes Gender Self-Concept of Ability in P.S. (R2=.06) .16 .09 .13 Number of Physical Sciences Courses (R2=.34) .09 Linking P.S. (R2=.03) .17 .09 .48 .20 Math Aptitude .19 Utility Of P.S. (R2=.05) Predicting Team Sports Self-Concept of Ability in Sports (R² = .09) Team Sports 10th grade (R² = .29) .15 .31 .04 Gender .24 .13 .29 Utility of Sports (R² = .08) .23 .27 .18 Liking Sports (R² = .05) Team Sports 12th grade (R² = .21) Ability Self-Concept R² = 8% .11 (.46) .28 Sex .21 Utility Value .36 (.53) Free Time Spent R² = 32% R² = 5% .19 .17 (.46) Importance Value R² = 4% Correlation: Sex – Time Spent = .14 Partial Correlation: Sex – Time Spent = .002 (controlling mediating variables) Conclusion In this sample, the gender differences in Utility Value were the strongest mediators of gender differences in math and physical science course enrollments. A slightly different pattern is emerging for math in the CAB study: Math Ability Self Concept is having a stronger effect. In this sample, the gender differences in all three expectancy – value beliefs mediated the gender differences in involvement in sports. What about College Course Choices? MSALT DESIGN Wave 1,2 3,4 5 6 7 8 9 Grade 6 7 10 12 12+2 12+6 12+9 Age 12 13 16 18 20 24 27 Year 83-'84 84-'85 88 90 92 96 99 Specific Sample Characteristics for Analyses Reported Today Those who participated at Wave 8 (age 25) Female N = 791 Male N = 575 Those who completed a college degree by Wave 8 Female N = 515 Male N = 377 Analyses: Within Sex Discriminant Function Analyses Use 12th grade Domain Specific Ability SCs and Values to predict College Major at age 25 Use age 20 General Ability SCs and Occupational Values to predict College Major at age 25 Analyses 2: Between Sex Logistic regression to test for mediators of sex differences in college Math/Engineering/Physical Science majors Time 1 Measures: th 12 Grade Math/Physical Science Self-Concept of Ability Math/PS Value and Usefulness Biology Self-Concept of Ability Biology Value and Usefulness English Self-Concept of Ability English Value and Usefulness High School Grade Point Average Sex Differences in Domain Specific Self Concepts and Values Self Concept and Value at Age 18 by Sex 5.5 5 Mean Value 4.5 4 Female 3.5 Male 3 2.5 2 t ep c n e M / ath lu Va i Sc M / ath i Sc lf Se Co gy o ol Bi l Se pt ce n o fC o Bi e alu V gy lo gli n E sh lf Se nc Co t ep E li ng sh lue Va Fi A GP l na Time 2 Measures: Age 20 Ability-Related Math/Science General Ability Self Concept Intellectual Ability Self Concept Efficacy for jobs requiring math/science Relative ability in logical and analytical thinking High School Grade Point Average Time 2 Measures: Occupational Values Job Flexibility Mental Challenge Opportunity to be creative and learn new things Working with People Does not require being away from family Working with others Autonomy Own Boss Time 2 Measures: Comfort with Job Characteristics Business Orientation: Comfort with tasks associated with being a supervisor People Orientation: Comfort working with people and children Sex Differences in General Self Concepts and Values 6 5.5 Mean Value 5 4.5 4 3.5 3 2.5 A y y t t pt GP t ed ilit ge ted en om ple e l n ep b n n n d i c o a e c e x ie e n n to ri ll en Fin Or F le ha Co Au hP Co ep eO t s f C f l e d i l e l s l p u n w l e I o ta Se Se alu Va sin Pe al en in g lu e *V ce u u k a M t r n B V o e ie le c alu /Sc eW t el V h u n * t l I Va Ma Female Male Time 3 Measures: Age 25 Final College Major Occupation at Age 25: Coded into Global Categories based on Census Classification Criteria Sex Differences in College Majors 120 100 Frequency 80 Female 60 Male 40 20 0 Math/Science Biology Business Social Science Sex Differences in Occupations Occupation at Age 25 by Sex 160 140 Frequency 120 100 Female 80 Male 60 40 20 0 Math/Science Biology Business Domain Specific Attractors: + Self Concepts and Values + Domain Specific Detractors: Anxieties Non-Domain Detractors: + Values and Self Concepts Academic Choice - + Non-Domain Attractors: General Achievement Predicting Women’s Math/Engineering/Physical Science (M/E/PS) and Biological Science College Major from Domain Specific SCs and Values at 18 Predicting Science vs. Other College Major Final GPA Math/sci value Math/sei self concept Predicting Biology vs. Other College Major 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 Discriminant Function Coefficient English value Math/Sci Value Biology self concept Value Biology -0.4 -0.2 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 Discriminant Function Coefficient 0.8 1 Predicting Women’s M/E/PS and Biological Science College Major from General Self-Concepts and Values at 20 Predicting Math /Science vs. Other College Major Working with people Final GPA Intellectual Self Concept Pridicting Biology vs. Other College Major Math/Sci Self Concept -0.4 -0.2 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 Discriminant Function Coefficient 0.8 1 Value working with people People Oriented Math/sci Self Concept 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 Discriminant Function Coefficient 0.7 0.8 Predicting Men’s M/E/PS and Biological Science College Major from Domain Specific SCs and Values at 18 Predicting Science vs. Other College Major Final GPA Math self concept Math/sci value Predicting Biology vs. Other College Major 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 Discriminant Function Coefficient Final Gpa Biology self concept Biology Value 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 Discriminant Function Coefficient 0.8 0.9 Predicting Men’s M/E/PS and Biological Science College Major from General SelfConcepts and Values at 20 Predicting Math/Science vs Other College Major People oriented Value Working with People Predicting Biology vs. Other College Major Final GPA Math/Sci -0.4 Value flexibility -0.2 0 0.2 0.4 Discriminant Function Coefficients 0.6 0.8 Math/Sci Self Concept Value working with people Value mental challenge Final GPA People Oriented Business Oriented -0.4 -0.3 -0.2 -0.1 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 Discriminant Function Coefficient 0.4 0.5 Mediation of Sex Differences Used logistic regression to assess the extent to which the Time 1 and Time 2 predictors explained the sex difference in majoring in Math/Engineering/Physical Science Step 1: Sex only Step 2: Sex plus all of Time 1 or Time predictors Time 1 Predictors of Science College Major l Fi na G PA Ma th Math SC Valu e er 2 Gend er 1 Gend 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 Coefficient B 0.5 0.6 0.7 Time 2 Predictors of Science College Major Final GPA M ath/SC Gender 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 Coe fficie nt B 0.4 0.5 0.6 Conclusions 1: Strong support for the predictive power of constructs linked to the Expectancy Value Model. Domain Specific SCs and Values push both women and men towards the related majors Some evidence that more general values can also push people away from M/S/PS majors and towards Biology-Related majors Sex differences in selection of M/E/PS college major are accounted for by Expectancy Value Model Predicting M/E/PS vs. Biology Major From General Self-Concepts and Values at 20 Business Oriented Final Gpa Intellectual Self Concept People Oriented Math/Sci self concept Value working with People Intellectual Self Concept -0.8 -0.6 -0.4 -0.2 0 0.2 0.4 Discriminant Function Coefficient for Females 0.6 0.8 Math/Science Self -Concept Final GPA Value Flexibility Business Oriented People Oriented Value Work With People -0.6 -0.5 -0.4 -0.3 -0.2 -0.1 0 0.1 0.2 Discriminant Function Coefficient for Males 0.3 Predicting M/E/PS vs. Social Science Major From Self-Concepts and Values at 18 Math/Sci self concept Math/Sci Value English Self Concept English Value Final GPA -0.6 -0.4 -0.2 0 0.2 0.4 Discriminant Function Coefficient for Females 0.6 0.8 Final GPA English Value English Self Concept Math/Sci Value Math/Sci self concept -0.6 -0.4 -0.2 0 0.2 0.4 Discriminant Function Coefficient for Males 0.6 0.8 Predicting M/E/PS vs. Social Science Major From General Self-Concepts and Values at 20 Final GPA Intellectual Self Concept Math/Sci Value 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 Discriminant Function Coefficient for Females Final Gpa Math/Sci Value Intellectual SelfConcept 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 Discriminant Function Coefficient for Males 0.7 0.8 Conclusions 2 Even stronger support for both the push and pull aspects of the Eccles et al. Expectancy Value Model Strong evidence that valuing having a job that allows one to work with and for people pushes individuals away from M/E/PS majors and pulls them toward the Biological Sciences Analyses 3 Now lets shift to the second set of analyses: those linking self concepts and values from ages 18 and 20 to occupational plans at age 20 and actual occupations at age 25 Predicting M/E/PS vs Biology Occupations at 25 from Self Concepts and Values at 18 Value Biology Final GPA Math/Sci self concept -0.4 -0.2 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 Discriminant Function Coefficient for Females 0.8 Final GPA Math/sci self concept Math/sci value 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 Discriminant Function Coefficient for Males 0.8 Predicting M/E/PS vs Biology Occupation at 25 from General Self Concepts and Values at 20 Final GPA Value Flexibility Value Math/Sci Value Working with People People Oriented -0.8 -0.6 -0.4 -0.2 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 Value Autonomy Discriminant Function Coefficient for Females Value Working with People -0.7 -0.6 -0.5 -0.4 -0.3 -0.2 -0.1 Discriminant Function Coefficient for Males 0 Predicting M/E/PS vs Business Occupations at 25 From Self Concepts and Values at 18 Math/sci Value Math/Sci Self Concept Final GPA 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 Discriminant Function Coefficient for Females Biology Self Concept Final GPA Value Biology Math/Sci Self Concept Math/Sci Value 0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 Discriminant Function Coefficient for Males 0.8 Predicting M/E/PS vs Business Occupation at 25 from General Self Concepts and Values at 20 Value Flexibility Value Mental Challenge Value Working with People Intellectual Self Concept Math/Sci Value -0.4 People Oriented -0.2 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 Intellectual Self Concept Discriminant Function Coefficient for Females Value Working People Value flexibility Math/Sci Self Concept Final GPA -0.6 -0.4 -0.2 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 Discriminant Function Coefficient for Males 0.8 Conclusions Expectancy Value Model provides a good explanatory framework for understanding both individual differences and sex differences in educational and occupational choices What about Gender Roles? Role of Traditionality in Terms of Family Role of Gender Role Stereotypes of Achievement Domain The Impact of Girls’ Gender-Role Beliefs on their Educational and Occupational Decisions. Self-Concept of Abilities Gender-Role Beliefs Achievement-Related Decisions Content •High school courses taken •Gender stereotypes of ability and value •Belief that women’s domain is in the home Values •Occupational aspirations •College major •Occupation at age 20 Expectations for Adult Responsibilities Status and Expected Labor Force Participation •Aspire to a family flexible job •Status of educational and occupational aspirations Figure 7. Traditionality, Values, Expectations of Adult Responsibilities, and Aspirations – Theoretical Model. Importance of Children GPA Importance of career Traditionality Status/Family Flexible Achievement Choices •Value of family flexible occupation •Status of occupational aspiration •Status of age 20 occupation Degree of Responsibility for Income SES Degree of Responsibility for Childcare and Household •Status of age 20 salary What About Gender Role Stereotypes? Figure 3.Gender Stereotypes of Math, Self-Concept, Values & Math/Physical Science Outcomes – Theoretical Model. 10th Grade Math Self-Concept of Ability Math Ability Stereotype 7th Grade Math Self-Concept of Ability 10th Grade Physical Science Self-Concept of Ability Math and Physical Science Achievement Choices •Number of high school courses taken •Occupational aspirations •College major Math Value Stereotype 7th Grade Math Value 10th Grade Math Value 10th Grade Physical Science Value Note: The paths between the stereotype variables and the outcomes are free. •Current occupation CONCLUSIONS General psychological model works very well across domains Values are key and yet they are often neglected in studies of gender differences while efficacy/ability selfconcepts and over emphasized Gender-role ideology is central to acquisition of gendered values Gendered values help predict both sex differences and individual differences within sex in activity choice Anticipated costs may be critical in long term choices Applications Interventions to increase the participation of females in M/E/PS need to focus on increasing women’s understanding that M/E/PS and Informational Technology jobs can help people and do involve working with people as well as increasing their confidence in their ability to succeed in these fields. Characteristics of Effective Classrooms Frequent Use of Cooperative Learning Opportunities Frequent Use of Individualized Learning Opportunities Infrequent Use of Competitive Motivational Strategies Frequent Use of Hands-On Learning Opportunities Frequent Use of Practical Problems as Assignments Active Career and Educational Guidance Aimed at Broadening Students’ View of Math and Physical Sciences Frequent Use of Strategies Designed to Create Full Class Participation The End Thank You More details and copies can be found at www.rcgd.isr.umich.edu/garp/