File

advertisement

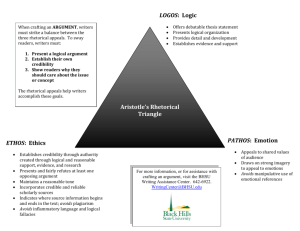

Essay Project 1, continued: Analyzing and Interpreting Rhetorical Stance From Summary to Analysis Now that you are skilled in the art of summary, you have a good foundation to stand on as you write your first paper. It is vital that you recognize the main idea and main points of a text so you can summarize that text; however, to become a successful creator of your own arguments, you must also recognize the rhetorical tools used by great writers. In other words, you know what they said, but how did they say it? Summary vs. Analysis A Summary requires you to use your own words to present the ideas of a text. A summary is shorter than the original text. A Rhetorical Analysis Essay requires you to move beyond simply telling what a text says; you must also discuss how the text is written. i.e. How does the author make an argument/thesis? What do you mean by “rhetorical analysis”? Rhetorical Analysis can sound confusing at first, so let’s take a closer look. Rhetoric is defined as “the art of persuasive or effective speaking or writing.” Analysis is the process of separating something into its parts. So, in a rhetorical analysis essay we take a close look at an argument/thesis and examine how different aspects of the essay reinforce that argument. Start with a close reading. In other words, annotate the text. What should I look for while I read? First, ask yourself “What is the author trying to say in this text?” In other words, what’s the point? Then, identify the audience. The intended reader of a text is very important in determining how effective the author is at presenting his/her ideas. What questions does the author address (directly or indirectly)? How does the author structure the text? What are the key parts, and how do they relate to one another and the thesis? Preparing continued… What evidence does the author use to support his thesis? How persuasive is the evidence? What strategies does the author use to generate interest in the argument and to persuade readers of its merit/importance? Aristotle’s Appeals: Ethos or The Ethical Appeal Logos or The Logical Appeal Pathos or The Emotional Appeal The Appeals: Ethical “Ethical appeals support the credibility, moral character, and good will of the argument’s creator” (Lunsford 168). To identify ethical appeals, ask yourself if the author is trustworthy, credible, and reliable. In other words: Is this person an authority figure on this subject? The Appeals: Logical The logical appeal includes facts to support the argument, as well as “firsthand evidence drawn from observations, interviews, surveys and questionnaires, experiments, and personal experience. Additionally, this appeal uses secondhand evidence drawn from authorities, the testimony of others, statistics, and other print and online sources” (Lunsford 168). Example: “It is well for us to remember that, in an age of increasing illiteracy, 60 percent of the world’s illiterates are women. Between 1960 and 1970, the number of illiterate men in the world rose by 8 million, while the number of illiterate women rose by 40 million” (from Adrienne Rich’s “What Does a Woman Need to Know?”). The Appeals: Emotional “Emotional appeals stir our emotions and remind us of deeply held values” (Lunsford 167). Some critics say emotional appeals manipulate the audience, but a good reader/interpreter can determine the fairness of the appeal as it relates to the argument. Identifying the Elements of an Argument When analyzing an argument, look for these common features: Claims (statements of fact, opinion, or belief that form the backbone of an argument) Reasons (These support the claims. Without good reasons, claims have no foundation on which to stand.) Assumptions (A writer expects his audience to hold certain assumptions. Cultural differences often point to different assumptions.) Evidence (the support) Qualifiers (words like few, often, in these circumstances, rarely, etc.. For example: “Grading damages learning” is less precise than “Grading can damage learning in some circumstances.”) Identifying Fallacies Fallacies are often viewed as flaws that damage the effectiveness of an argument. But sometimes they work. That’s why it’s important to look at every aspect of a rhetorical situation before you write-off an argument as “poor” or “unsound.” Verbal Fallacies Ad hominem—Makes a personal attack rather than focusing on the issues. Who cares what that fat loudmouth says about health care, anyway? Guilt by Association—Attacks someone’s credibility by linking her with someone untrustworthy. She does not deserve reelection; her husband had a gambling problem. False Authority—Using celebrities to testify to the greatness of a product about which they probably know very little. He’s today’s greatest basketball player—and he banks at National Mutual! Fallacies, continued Bandwagon—Suggests a great movement is underway— everybody’s doing it, and you should too! This new phone is everyone’s must-have item. Do you have one yet? Flattery—Tries to persuade readers by suggesting that they are thoughtful, intelligent, or perceptive enough to agree with the writer. You have the taste to recognize the superlative artistry of Kay Jewelry. In-Crowd Appeal—Invites readers to identify with an admired and select group. Want to know a secret that more and more of Milledgeville’s successful young professionals are finding out about? It’s Mountain Brook Condominiums! Fallacies, continued Veiled Threat—Frightens readers into agreement by hinting that they will suffer adverse consequences if they don’t agree. If Public Service Electric Company does not get an immediate 15 percent rate increase, its services to you may be seriously affected. False Analogy—Makes a comparison between two situations that are not alike in important respects. The volleyball team’s sudden descent in the rankings resembled the sinking of the Titanic. Fallacies, continued Begging the Question—A kind of circular argument that treats a debatable statement as if it had been proved true. TV news covered that story well; I learned all I know about it by watching TV. Post Hoc Fallacy—Assumes that just because B happened after A, it must have been caused by A. We should not rebuild the town docks because every time we do, a big hurricane comes along and damages them. Fallacies, continued Non Sequitur—Attempts to tie together two or more logically unrelated ideas as if they were related. If we can send a spaceship to Mars, then we can discover a cure for cancer. Either-Or Fallacy—Insists that a complex situation can have only two possible outcomes. If we do not build the new highway, businesses downtown will be forced to close. Hasty Generalization—Bases a conclusion on too little evidence or on bad or misunderstood evidence. I couldn’t understand the lecture today, so I’m sure this course will be impossible. Fallacies, continued Oversimplification—Claims an overly direct relationship between a cause and an effect. If we prohibit the sale of alcohol, we will get rid of binge drinking. Straw Man—Misrepresents the opposition by pretending the opponents agree with something that few reasonable people would support. My opponent believes that we should completely do away with the prison system. I disagree. In your first essay… …you will write a rhetorical analysis in which you’ll apply what we’ve learned today to a text from Unit 1. You’ll look at how the writer makes his or her argument. What appeals are used? What fallacies? What claims/reasons? Etc. Questions?