Dickinson's terse, frequently imaginistic style is even more modern

advertisement

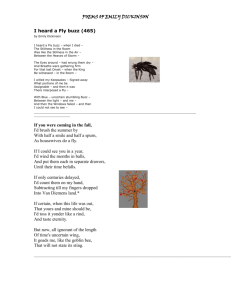

Emily Dickinson The Belle of Amherst Biography Born December 10, 1830 the second of three children to a Calvinist family in Amherst, MA. Father was a lawyer and one of the wealthiest and most respected citizens in the town, as well as a conservative leader of the church Educated at Amherst Academy. At 17, began college at Mount Holyoke Female Seminary; she became ill the spring of her first year and did not return. It was later, during her mid-twenties that Emily began to grow reclusive. Biography She spent sociable evenings with guests such as Samuel Bowles, editor of the Springfield Daily Republican She also enjoyed dancing, buggy rides, parlor games, and other forms of entertainment until she began to seclude herself Around 1860, she stopped visiting with other people and became a recluse She almost always wore white. She often lowered snacks and treats in baskets to neighborhood children from her window, careful never to let them see her face. Biography By the 1860s, she lived in almost total physical isolation from the outside world, but actively maintained many correspondences and read widely. She wrote 1775 poems, but only seven of them published in her life time. Before her death, she asked her sister to burn all her poems. However, her sister published them instead. Dickinson’s Poetry Dickinson was able to create a very personal and pure kind of poetry. Regular meter—hymn meter and ballad meter, also known as Common meter – Quatrains – Alternating tetrameter and trimeter – Often 1st and 3rd lines rhyme, 2nd and 4th lines rhyme in iambic pentameter The use of dashes Influenced by nature and spiritual themes Dickinson’s Poetry Dickinson’s terse, frequently imaginistic style is even more modern and innovative than Whitman’s Her poetry exhibits great intelligence and often evokes the agonizing paradox of the limits of the human consciousness trapped in time. The subjects of Dickinson’s poetry are the traditional ones of love, nature, religion, and immortality Her poetry is also notable for its technical irregularities Other characteristics of her style include sporadic capitalization of nouns; convoluted and ungrammatical phrasing; off-rhymes; broken meters; bold, unconventional, and often startling metaphors; and aphoristic wit. Dickinson’s Publishing Career Dickinson began a correspondence with Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a local intellectual, journalist, and anti-slavery activist She asked Higginson for advice with her poetry Higginson responded with much praise and gentle criticism, but he advised her against publishing her poetry because of its raw form and subject matter Higginson became Dickinson’s intellectual mentor. Even though he admitted feeling out of her league in poetical talent, he ultimately did not recognize the worth of her poetry At the time of her death, only seven of her poems had been published. Posthumous Publication After her death, her poems were heavily edited and published by Higginson and friend Mabel Loomis Todd. Thomas Johnson produced a collection of Dickinson’s more than 1700 poems in three volumes in 1955; he restored her original capitalization and punctuation. What’s the Difference? EDITED VERSION BECAUSE I could not stop for Death, He kindly stopped for me; The carriage held but just ourselves And Immortality. We slowly drove, he knew no haste, And I had put away My labor, and my leisure too, For his civility. We passed the school where children played, Their lessons scarcely done; We passed the fields of gazing grain, We passed the setting sun. ORIGINAL VERSION Because I could not stop for Death, He kindly stopped for me; The carriage held but just ourselves And Immortality. We slowly drove, he knew no haste, And I had put away My labor, and my leisure too, For his civility. We passed the school, where children strove At recess, in the ring; We passed the fields of gazing grain, We passed the setting sun. An excerpt of poem 712, or “Because I could not stop for Death, called “The Chariot” by Higginson and Todd. On the left is the edited version; on the right, the original. Note the major changes in lines 9 and 10. Dickinson’s Legacy Dickinson died May 15, 1886 of nephritis (kidney disease). Dickinson is considered influential to poets such as Adrienne Rich, Richard Wilbur, Archibald MacLeish, and William Stafford. Along with Walt Whitman, Dickinson is one of the two giants of American poetry of the 19th century. The Dickinson Homestead in Amherst, Massachusetts The Dickinson Homestead in Amherst, Massachusetts (garden) The Dickinson Homestead in Amherst, Massachusetts (bedroom) The Dickinson Homestead in Amherst, Massachusetts (Dress) If you were coming in the Fall If you were coming in the Fall, I ’d brush the Summer by With half a smile, and half a spurn, As Housewives do a Fly. If certain, when this life was out– That yours and mine, should be I ’d toss it yonder, like a Rind, 15 And take Eternity– If I could see you in a year, 5 I ’d wind the months in balls– And put them each in separate Drawers, For fear the numbers fuse– But, now, uncertain of the length Of this, that is between, It goads me, like the Goblin Bee— That will not state—its sting. 20 If only Centuries delayed, I ’d count them on my Hand, 10 Subtracting ,till my fingers dropped Into Van Diemen’s Land. My life closed twice before its close My life closed twice before its close— It yet remains to see If Immortality unveil A third event to me So huge, so hopeless to conceive As these that twice befell. Parting is all we know of heaven, And all we need of hell. The Soul selects her own Society The Soul selects her own Society— Then—shuts the Door— To her divine majority— Present no more— Unmoved—she notes the Chariot’s—pausing— At her low Gate— Unmoved—an Emperor be kneeling Upon her Mat— I ’ve known her—from an ample nation— Choose one— Then—close the Valves of her attention— Like Stone— 5 10 Much Madness is divinest Sense Much Madness is divinest Sense— To a discerning perceptive Eye— complete Much Sense—the starkest Madness— ‘Tis the Majority succeed In this, as All, prevail— Agree Assent—and you are sane— Demur—you're straightway dangerous— Object And handled with a Chain— Success is counted sweetest Success is counted sweetest By those who ne'er succeed. To comprehend a nectar Requires sorest need. Not one of all the purple Host Who took the flag today Can tell the definition So clear of Victory As he defeated—dying— On whose forbidden ear The distant strains of triumph Burst agonized and clear! Because I could not stop for Death Or rather—He passed Us— The Dews drew quivering and chill— For only Gossamer, my Gown— My Tippet—only Tulle— Because I could not stop for Death— He kindly stopped for me— The Carriage held but just Ourselves— And Immortality. We slowly drove—he knew no haste And I had put away My labor and my leisure too, For his Civility— 5 We paused before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground— The Roof was scarcely visible— 15 The Cornice—in the Ground— We passed the School, where Children strove At Recess—in the Ring— 10 We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain— We passed the Setting Sun— Since then— ’tis Centuries—and yet Feels shorter than the Day I first surmised the Horses’ Heads Were toward Eternity— 20 This is my letter to the World This is my letter to the World That never wrote to me— The simple News that Nature told— With tender Majesty Her Message is committed To Hands I cannot see— For love of Her—Sweet countrymen— Judge tenderly—of Me Hope is the thing with feathers Hope is the thing with feathers That perches in the soul, And sings the tune without the words, And never stops at all, And sweetest in the gale is heard; And sore must be the storm That could abash the little bird That kept so many warm. I've heard it in the chillest land, And on the strangest sea; Yet, never, in extremity, It asked a crumb of me.