'Smart Baby' Products Reeling In Parents

Jacqueline L. Salmon and Jay Mathews

Copyright 2000, The Washington Post Co. All Rights Reserved

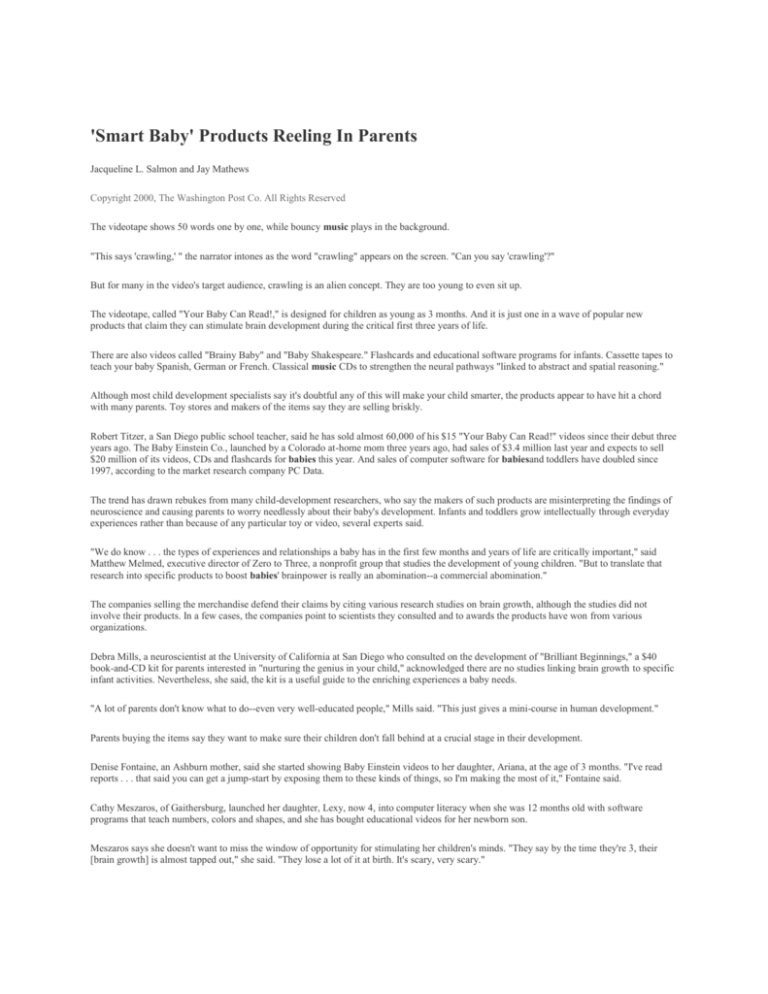

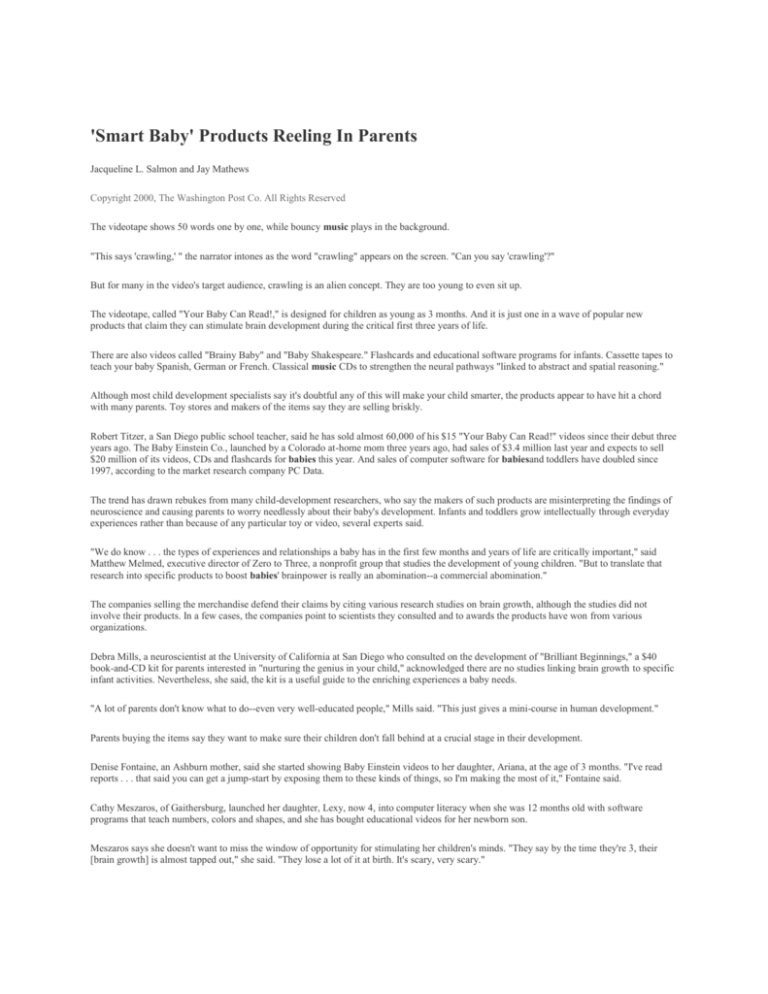

The videotape shows 50 words one by one, while bouncy music plays in the background.

"This says 'crawling,' " the narrator intones as the word "crawling" appears on the screen. "Can you say 'crawling'?"

But for many in the video's target audience, crawling is an alien concept. They are too young to even sit up.

The videotape, called "Your Baby Can Read!," is designed for children as young as 3 months. And it is just one in a wave of popular new

products that claim they can stimulate brain development during the critical first three years of life.

There are also videos called "Brainy Baby" and "Baby Shakespeare." Flashcards and educational software programs for infants. Cassette tapes to

teach your baby Spanish, German or French. Classical music CDs to strengthen the neural pathways "linked to abstract and spatial reasoning."

Although most child development specialists say it's doubtful any of this will make your child smarter, the products appear to have hit a chord

with many parents. Toy stores and makers of the items say they are selling briskly.

Robert Titzer, a San Diego public school teacher, said he has sold almost 60,000 of his $15 "Your Baby Can Read!" videos since their debut three

years ago. The Baby Einstein Co., launched by a Colorado at-home mom three years ago, had sales of $3.4 million last year and expects to sell

$20 million of its videos, CDs and flashcards for babies this year. And sales of computer software for babiesand toddlers have doubled since

1997, according to the market research company PC Data.

The trend has drawn rebukes from many child-development researchers, who say the makers of such products are misinterpreting the findings of

neuroscience and causing parents to worry needlessly about their baby's development. Infants and toddlers grow intellectually through everyday

experiences rather than because of any particular toy or video, several experts said.

"We do know . . . the types of experiences and relationships a baby has in the first few months and years of life are critically important," said

Matthew Melmed, executive director of Zero to Three, a nonprofit group that studies the development of young children. "But to translate that

research into specific products to boost babies' brainpower is really an abomination--a commercial abomination."

The companies selling the merchandise defend their claims by citing various research studies on brain growth, although the studies did not

involve their products. In a few cases, the companies point to scientists they consulted and to awards the products have won from various

organizations.

Debra Mills, a neuroscientist at the University of California at San Diego who consulted on the development of "Brilliant Beginnings," a $40

book-and-CD kit for parents interested in "nurturing the genius in your child," acknowledged there are no studies linking brain growth to specific

infant activities. Nevertheless, she said, the kit is a useful guide to the enriching experiences a baby needs.

"A lot of parents don't know what to do--even very well-educated people," Mills said. "This just gives a mini-course in human development."

Parents buying the items say they want to make sure their children don't fall behind at a crucial stage in their development.

Denise Fontaine, an Ashburn mother, said she started showing Baby Einstein videos to her daughter, Ariana, at the age of 3 months. "I've read

reports . . . that said you can get a jump-start by exposing them to these kinds of things, so I'm making the most of it," Fontaine said.

Cathy Meszaros, of Gaithersburg, launched her daughter, Lexy, now 4, into computer literacy when she was 12 months old with software

programs that teach numbers, colors and shapes, and she has bought educational videos for her newborn son.

Meszaros says she doesn't want to miss the window of opportunity for stimulating her children's minds. "They say by the time they're 3, their

[brain growth] is almost tapped out," she said. "They lose a lot of it at birth. It's scary, very scary."

But educators and researchers say there is no cause for such worrying. They say that parents who read and play with their babies, respond to their

cues and show them affection are giving them all that's needed for optimum brain development. What matters are "things that good parents have

known how to do since the beginning of time," said Robert Slavin, an educational researcher at Johns Hopkins University.

Critics of the smart-baby products say those who market them are confusing neurology--the study of the brain as a spongy, grayish lump--and

psychology, the study of human behavior.

There are many psychological studies--having nothing to do with brain cells--showing that very young children deprived of normal experiences

develop emotional or intellectual disabilities. Meanwhile, neurologists have discovered that the number of synapses--vital connection points--in

the brain increases enormously from before birth to age 3 and begins to drop in early puberty.

But scientists say there is no evidence that this surge of synapses will get an extra boost from particular images, sounds or activities, although

brain growth can decrease when children are severely abused or neglected.

"There are no data to show that with each new experience you're adding synaptic connections," said Harry Chugani, director of the PET center at

Children's Hospital of Michigan, who has been at the forefront of research into children's brain development.

But many of the new educational products come with claims that science has indeed demonstrated a link between brain growth and specific

experiences.

"So Smart," a video produced by the Baby School Company Inc., tells parents that it "presents images scientifically proven to stimulate your

infant's developing mind."

In the video, thick-lined drawings and words flow along the screen accompanied by classical music. Company co-founder Scott Tornek said his

wife, a clinical psychologist, designed images that would capture babies' attention.

Some critics of such videos say they could actually impede a baby's development if they were to cut down on the amount of interaction between

parent and child. Tornek and other video producers say they encourage parents to watch the tapes with their children.

The Baby Einstein videos feature babies' faces, nature scenes and close-up views of brightly colored toys. On the soundtrack are nursery rhymes

in various languages, Shakespearean poetry and classical music.

"What we are saying is that you can use television to offer 'field trips' for your baby into these beautiful forms of human expression," said Julie

Aigner-Clark, founder of the Baby Einstein Co. "We tell parents to sit with their babies in front of the TV, watch these pictures together and . . .

tell them what they are, how they work."

The music CD that comes with Brilliant Beginnings says that "the parts of the brain your baby will later use for higher-level intellectual

activities, such as reading and math, are stimulated by exposure to complex music."

Researchers say there have been relatively few studies on how music affects intelligence. A widely publicized study in the early 1990s said that

college students' test scores rose after they listened to a Mozart sonata, but that link has not held up in other studies.

As for the products that claim to teach foreign languages to babies, researchers say that exposing an infant to a second language is unlikely to

have any benefits unless the child hears it constantly.

And although school officials have stressed the importance of reading aloud and giving books to children before they start kindergarten, several

educators are skeptical about the products designed to teach babies how to read.

Titzer, who developed the "Your Baby Can Read!" video, said he used such videos with his own two daughters and they were able to recognize

words in books at 9 months.

Researchers say it is possible for a child under the age of 2 to read--to look at a printed word, say it aloud and point to an object to demonstrate

the word's meaning. But they also question whether developing that skill at such a young age will make the child a better reader in later years.

George Forman, a professor of early childhood education at the University of Massachusetts, said that drilling very young children with

flashcards or videos could make it harder later for them to learn to sound out words that weren't covered in those lessons.

The best advice for raising a smart baby, said Robert Pianta, professor of clinical psychology at the University of Virginia, is "relax and enjoy

playing with your children."