bauman's cash flow method

advertisement

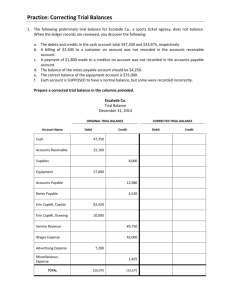

BAUMAN'S CASH FLOW METHOD Part I - Theory and Mnemonics When I studied and learned financial accounting, one of the most difficult topics for me was cash flow. There were two primary reasons for my difficulty. The first reason was that I had to memorize everything - I could not use any type of notes during an exam. That requirement in turn caused the second reason for my difficulty. It meant that I had to have some way of remembering the cash flow process long enough to be tested on it; who cared if I remembered it after the exam? I wouldn't care because at a later date I could always look up the process. For the exam, though, I relied on a mnemonic device, a mental way to make my memorization task easier. What I used was a key ingredient so that if I remembered just a small part, I could easily figure everything else out without having to remember all aspects of it. In other words, rather than trying to memorize all of the cash flow "formulae" by the author of my text, could I instead focus on one small part, memorize just that part, and by knowing and applying the basic accounting equation solve the rest of the puzzle? I found the positive answer in the Notes Payable account. Notes Payable (abbreviated herein as N/P), a liability account, became the key to the puzzle when I realized that its behavior mirrored the cash flow process. For example, if a promissory note is signed and the funds are received, two things happen when the transaction is journalized and then posted by the borrower. First, the Cash account increases by the amount of the note because the business received the cash. [Note: to identify specific accounts in the general ledger from items of general use, I’ll use upper case letters; in this case, a capital "C" to distinguish the Cash account from cash, the legal tender.] And second, the N/P account increases by the identical amount to show the newly created liability. Later, if the note is partially or wholly repaid (ignoring interest for now), the reverse happens to the accounts: cash is used to pay the lender, so the Cash account decreases, and along with the cash goes part or all of the liability N/P decreases as well. In terms of debits and credits when the note was signed and the cash received, the Cash account was debited and N/P was credited. Later, when the note is partially or wholly paid, Cash is credited and N/P is debited. My mnemonic key of using N/P analysis was therefore a simple one: if the Cash account increased because of an increase in the N/P account, then positive cash flow occurred. If the Cash account decreased because cash was used to pay part or all of the N/P, then negative cash flow occurred. In debit and credit terms, if N/P increased (with a credit), it meant that the matching debit was to Cash because the business received the cash, and cash flow was positive. If, on the other hand, N/P decreased with a debit because the matching credit was used to decrease the Cash account, it meant that cash was used to decrease the liability and cash flow was therefore negative. We can draw the conclusion about N/P cash flow by looking only at the N/P account itself; we don't have to look inside the Cash account. Given the relationship of debits and credits on the N/P account, I drew the relationship thus (and “tagging” will be explained later): Notes Payable Debits Credits are Are account decreases Account increases and equal and equal Cash Flow Decreases Cash Flow Increases or Or Cash Flow "Tag" negative Cash Flow "Tag" positive (-) (+) Of course, not all changes to N/P involve actual cash flow. For example, when an account payable (A/P) is exchanged for an N/P, no cash is immediately flowing, even though N/P is credited, and the N/P credit would normally indicate positive cash flow. The key here is that the A/P - N/P "swap" takes place without cash being involved; Cash is not one of the accounts used at the time of the “swap.” Only later does the Cash enter the system – when the maker pays the note. As we analyze the movement of amounts through the accounts, we want to assure ourselves that the transaction currently or eventually involves the Cash account; this is why we exclude the Cash account in our analysis. This topic will be discussed further in the section on asset accounts below. I then extended the logic of the N/P cash flow to all liability and equity accounts because I knew that the Accounting Equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity) would hold the logic true because they’re on the same side of the Equation. So my mnemonic key logically extended to: All Liability and Equity Accounts Debits Credits are are account decreases account increases and equal and equal Cash Flow Decreases Cash Flow Increases or or Cash Flow "Tag" negative Cash Flow "Tag" positive (-) (+) Once I established that all liability and equity accounts behaved identically (that is, positive cash flows were caused by credits and negative cash flows were caused by debits), I then turned my attention to all asset accounts except Cash. Due to the Accounting Equation, asset accounts behave the opposite of liability and equity accounts but not in cash flow terms! I then extended the mnemonic key to non-Cash asset accounts by reversing the account action of the N/P key: All Non-Cash Asset Accounts Debits Credits are are account increases but equal Cash Flow Decreases or Cash Flow "Tag" negative (-) account decreases but equal Cash Flow Increases or Cash Flow "Tag" positive (+) The Inventory account comes to mind to solidify the non-Cash asset account cash flow logic: If cash is used to buy inventory, the Cash account decreases with a credit while the Inventory account increases with a debit. Now remember that when we are examining the accounts for cash flow, we DO NOT examine the Cash account; we are trying to explain the changes in the Cash account by looking at non-Cash accounts. In other words, to determine the Cash account changes we examine all accounts except the Cash account (see the endnotes in Part V). Therefore, in analyzing the cash flows associated with the Inventory account example here, we ignore the transaction's effect on the Cash account and focus only on the non-Cash account part of the transaction. Therefore, we use the Inventory account to see what's happened. Since the Inventory account increased with the purchase of inventory, we can say that negative cash flows occurred because we used cash to pay for the inventory. This relationship exists for all non-Cash asset accounts; for example, buying office supplies with cash decreases cash (cash outflows) and increases the Office Supplies balance. What about the cash flow effect of credit purchases of inventory or other non-Cash assets? If inventory had been purchased on credit, Accounts Payable (A/P) would have been credited. Since A/P is a liability, if it increases there is theoretically a positive cash flow; not until the A/P decreases with a cash payment, however, is there actual negative cash flow. The logic is not detoured because we are focusing on the non-Cash asset Inventory account - since it increased, cash flow is negative. We can say, however, that the amount of cash flow negativity can be affected by the change in the A/P account if some amount of inventory was purchased on credit. Knowing now that changes in non-Cash asset accounts may imply cash flows where none currently exist but may in the future, let's use another example. Let's assume an accounts receivable (A/R) customer's balance is exchanged for a note receivable (N/R). The credit to A/R would indicate a positive cash flow under my method; it is offset, though, by the simultaneous debit to N/R. Only when the maker honors the N/R and we actually receive the cash will we experience the positive cash flow as indicated by the credit to N/P and the debit to Cash. I believe it's clear how we can analyze non-Cash asset accounts: If a non-Cash asset account balance increased over the period it is safe to assume under this method that negative cash flows occurred. It is also safe to assume that if a non-Cash asset account decreased, negative cash flows have resulted and they would therefore be included in the statement of cash flows. Closely related to these types of non-Cash transactions are asset accounts that are affected by "asset-for-asset swaps." For instance, when prepaid insurance is purchased for cash, there is negative cash flow. But what if the purchase is made on account through A/P? In this case, the purchase has no actual cash flow, even though there is a debit to the prepaid account, which under my method would indicate negative cash flow. This time, there is a matching credit to the A/P account instead of Cash, and because the debit and credit offset each other, no actual cash flow occurs when the policy is bought. Then, at the end of the accounting period, a portion of the prepaid "decays" and an adjusting entry removes the "decayed" part of the asset with a credit to the prepaid and moves it to an expense account with a debit. Even after the adjustment, no actual cash flow has occurred because the credit to the prepaid and the debit to the expense account offset and nullify any cash flow. Actual cash flow occurs when A/P is reduced with the payment to the creditor. To summarize what has been discussed so far, I'll shorten the diagrams: All Non-Cash Asset Accounts Debits Credits equal equal Cash Flow decreases Cash Flow increases (-) (+) All Liability Debits equal Cash Flow decreases (-) Accounts Credits equal Cash Flow increases (+) All Equity Accounts Debits Credits equal equal Cash Flow decreases Cash Flow increases (-) (+) Notice the common thread through the three types of accounts: from a cash flow perspective, debits cause negative cash flow and credits cause positive cash flow. We can now ask ourselves: Does this common thread extend to revenues and expenses? What do you think? Let's find out. When a cash sale of merchandise or service occurs, the Cash account is debited and Sales or Service Revenue is credited; i.e., the Revenue account increases (let's use "Revenue" as a generic Sales or Services Revenue account). Again, we don’t analyze the Cash account, but instead we look only at the Revenue account. Its balance increased with the posted credit, and because cash entered the accounts, positive cash flow resulted from the sale. Using our diagram, a cash sale looks like: All Revenue Debits are account decreases and equal Cash Flow Decreases or Cash Flow "Tag" negative (-) Accounts Credits are account increases and equal Cash Flow Increases or Cash Flow "Tag" positive (+) Looking at the cash flow positive and negative of the Revenue account, we can see that the logic does continue; the cash flow positive and negative are the same here as they are for the Asset, Liability, and Equity accounts. Here also the question may arise: What if the sale is made on credit - in other words, what if Revenue is credited and A/R is debited instead of Cash? Similar to the purchase on account of inventory, there will be no actual cash flow until the customer pays their account (our A/R) balance down; the posting of the cash received will then increase the balance in the Cash account, and the credit to A/R will reduce that account. Prior to the receipt of the customer's cash there will be theoretical cash flow because the Revenue account increased. However, the amount of the actual cash flow isn't known and doesn't happen until the customer pays their account down and our business physically gets the cash. We must also look at the A/R balance to see if it increased or decreased simultaneously to the Revenue account; that's discussed later. For now, though, let's turn to the expense accounts in general by looking at a utilities payment. As we begin our discussion on expense accounts, we'll combine all expense, drawing, and dividends accounts using one heading: All Expense/Drawing/Dividend Accounts Debits Credits are are account increases account decreases and equal and equal Cash Flow Decreases Cash Flow Increases or or Cash Flow "Tag" negative Cash Flow "Tag" positive (-) (+) We can combine these accounts because we will arrive at the same mathematical result against the equity whether we use a transaction involving a drawing, dividend, or an expense account because they all reduce the equity in the same way. When a utility bill is paid with cash, the Cash account balance decreases with a credit and the Utilities Expense account increases with a debit. Cash flow is negative due to the cash payment of the utility bill. Mathematically the same results occur with the Dividend and Drawing accounts. But a word of caution is appropriate here. Some expenses will always be cash flow neutral. For examples, depreciation and depletion, like other non-cash expenses, transfer and reduce asset amounts to expense accounts without ever involving cash. Be careful in your cash flow analysis regarding these types of accounts! Now we know that we can add all revenue, expense, drawing, and dividend accounts to those asset, liability, and equity accounts previously discussed. So where does that leave us? Simply put, the mnemonic key of N/P has given us a wealth of information solely by our remembering that borrowing cash will be credited to N/P and debited to the Cash account, reflecting a positive cash flow. We now have examined all the major account types and we have discovered that all of them behave like the N/P account itself: in analyzing cash flows, all non-Cash account debits are negative cash flows and all non-Cash account credits are positive cash flows. Can we diagrammatically summarize our findings? You bet. Here’s a summary diagram: All Non-Cash Debits are Cash Flow Decreases or Cash Flow “Tag” negative (-) Accounts Credits are Cash Flow Increases or Cash Flow “Tag” positive (+) I believe it's crucial in our analysis of cash flows to know what's "inside" our accounts. In textbooks, it's easy for the author to tell us that all of the A/R balance was caused by customer transactions (so that we don't have to see if N/R transactions occurred). Or we can be told in a given problem that prepaids were not created on credit. But in the "real world" such account balances are not as clear-cut. While my method works, you also have to apply some common accounting sense and knowledge to the account balances to help determine your answers, no matter how you arrive at the figures for the statement of cash flows. It’s also helpful to understand why we analyze all of the accounts except Cash to discover the magnitude of cash flows and whether the flows were positive or negative. If we use the Accounting Equation and modify it slightly, you’ll see why. Here is the standard equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity 1) If we split Cash from Assets, we have: 2) If we solve for Cash, we have: 3) If we use the symbol (delta) to mean “change in” and apply it to our revised Accounting Equation, we now have: Cash + Non-Cash Assets = Liabilities + Equity Cash = Liabilities + Equity – Non-Cash Assets Cash = Liabilities + Equity – Non-Cash Assets This means that we can examine the liabilities, equity, and non-Cash asset accounts for changes from one period to another and we will be able to explain the change in the Cash account. That’s why we examine only the non-Cash accounts when we are building the statement of cash flows. See the endnotes on the last page for a further explanation. It’s also helpful to understand that in theory all journal entries, except those involving Cash, have a neutral cash flow. For example, purchasing office supplies on account increases Office Supplies with the debit part of the journal entry, and A/P is increased by the credit part of the journal entry. Using my method, the credit to A/P is judged to be a positive cash flow and the debit to Office Supplies is judged to be a negative cash flow. However, no actual cash flow occurred because Cash was not one of the journal entries. The negative cash flow journal entry, the debit to Office Supplies, was offset by the positive cash flow journal credit entry to A/P. Only when the A/P balance decreases by paying the vendor with cash is there actual cash flow: the journal entry debit to A/P is matched by the journal entry credit to Cash. In this case, there is negative cash flow at the moment of payment. We are able to determine this negative cash flow because we are only looking at the non-Cash part of the transaction – the debit to A/P. We are not looking at the credit to Cash. Since the debit decreased A/P, we can therefore come to the reasonable conclusion that negative cash flow occurred because we know that the Cash account decreased to pay the A/P vendor. My method works because in a journal entry involving Cash we are really looking at the remaining non-Cash debit or credit part of the entry: if it’s a debit, negative cash flow results. If it’s a credit, positive cash flow results. Since we have now developed our knowledge of cash flow somewhat, what do we do with it? We use our knowledge and mnemonic key to analyze the various non-Cash accounts, which in turn will help us discover where the cash flows came from and where they were applied. However, the most important use of this knowledge will be to help you answer the homework problems and the chapter test questions!! Let's continue our examination of the cash flow process, but now we'll use some examples to cement the concept further. __________________________________________________________ Part II - Application In the real world as in your text, your compilation of information required to produce the statement of cash flows comes from the linking income statement between two successive year-end balance sheets and examination of the general ledger accounts (which is usually provided as "Additional Information" in your texts). Revenue and expense cash flows begin in the income statement for the accounting period, while non-Cash asset, liability, and equity accounts start the cash flow examination process by comparing the current end-of-period balance sheet with the balance sheet prepared at the end of the previous accounting period. Below is the income statement for the year ended December 31, 20X3, and the balance sheets dated December 31, 20X3 and 20X2, for Printer's Inc., a fictitious and growing company. Additional information about the 20X3 transactions is also shown following the statements. Printer's Inc. Income Statement For Year Ended December 31, 20X3 Sales Cost of goods sold Salaries and other operating expenses Interest expense Income tax expense Depreciation expense Loss on plant asset sale Gain on debt retirement Net income $630,000 $320,000 220,000 6,000 17,000 26,000 (589,000) (4,000) 18,000 $ 55,000 Printer's Inc. Balance Sheets December 31, 20X3 and 20X2 Assets Current assets: Cash Accounts Receivable Inventory Prepaid Insurance Total current assets: Long-term assets: Plant Assets Accum. Depr. Total assets Liabilities Current liabilities: Accounts Payable Interest Payable Income Tax Payable Total current liabilities: Long-term liabilities: Bonds Payable Total Liabilities Stockholders' Equity Contributed Equity: Common Stock, $1 par value Retained Earnings Total stockholders' equity Total liabilities and stockholders' equity 20X3 20X2 $36,000 70,000 89,000 12,000 $207,000 $17,000 50,000 75,000 10,000 $152,000 $245,000 (64,000) $388,000 $200,000 (52,000) $300,000 $45,000 8,000 25,000 78,000 $50,000 9,000 15,000 74,000 96,000 174,000 78,000 152,000 115,000 99,000 214,000 90,000 58,000 148,000 $388,000 $300,000 Additional Information about the 20X3 transactions: All accounts payable balances resulted from inventory purchases. Plant assets costing $85,000 were bought with $20,000 cash and $65,000 of bonds payable issued to the seller. Plant assets with an historical cost of $40,000 and associated accumulated depreciation of $14,000 were sold for cash. The result was a $4,000 loss. During the year, 25,000 more common stock shares were sold for $25,000. Bonds with a carrying value of $47,000 were retired during the year, costing $29,000 in cash, resulting in a gain of $18,000. Cash dividends of $14,000 were declared and paid. Interest expense equaled the amount paid in cash because bonds payable contract rates matched market rates; no premium or discount amount was involved. Our goal is to determine the cash flows involved with these statements while considering the Additional Information so we can prepare the statement of cash flows. When we finish, we’ll be able to explain the $19,000 increase in the Cash account between 20X2 and 20X3. Let's begin! We’ll use a process called "tagging" to identify cash flows. If you correctly "tag" cash flows as you analyze the accounts, your task will be greatly simplified. I will show you in the upcoming examples how to "tag" the cash flows. But for right now, "tagging" is very simply stated: cash inflows are positive "tag" suffixes (+); cash outflows are negative "tag" suffixes (-). You will use either of these two "tag" suffixes (+ or -) as you continue through the examples. Cash received from customers: Let's examine the revenue posted to Sales and revenue and collections posted to the A/R to determine cash flow from customers. Analyze the Sales account first. From the income statement we see that sales was $630,000. We know that the Sales account increased from $0 to $630,000 during the period (because Sales is a nominal account, it will start each accounting period with a zero balance). The Sales account increased to $630,000 by credits posted to it, matched by journal entry debits to Cash and/or A/R. From our Part I diagrams, we know that all non-Cash account credits are positive cash flows. So mark the $630,000 with a positive cash flow "tag" as a suffix: $630,000 + If all of the revenue had been from cash sales, the $630,000 would be the positive cash flow generated by cash received from our customers and the Cash account would have increased. Because the business also offers the option of credit sales to its customers, however, we must modify the revenue cash flow by any change in A/R. Compare the balance of this year's A/R account to last year's balance: we find that the current balance of $70,000 grew from the $50,000 balance at the end of the previous year. We now ask ourselves several questions to determine whether we apply a positive or negative cash flow "tag" to the absolute difference between the year-end balances (absolute difference is the arithmetic difference between two numbers without respect to their negative or positive values). The first question we ask is: Did the balance in A/R increase or decrease from last period? Answer: it increased. Next question: What type of account is A/R? Answer: it's a non-Cash asset account. Next question: What increases a non-Cash asset account, a debit or credit? Answer: a debit. Final question: is a debit a positive or negative cash flow? Answer: it's a negative cash flow. Now that you have determined that the change in A/R is a negative cash flow, "tag" the absolute difference between the two balances of $20,000 ($70,000 - $50,000) with a negative cash flow suffix "tag" and place it under the previously "tagged" Sales amount thus: $630,000 + 20,000 and algebraically add them using their "tags" as mathematical operators: $630,000 + sales revenue 20,000 - A/R balance change $610,000 + cash inflow from customers The result is a $610,000 positive cash flow. Stopping for a moment, let's see if our calculation makes "cash flow sense." The business accounted for $630,000 in sales but part of that total came from credit buyers, as evidenced by the increase in A/R. Therefore, not all of the Sales account can be cash received from customers. Only the amount of sales not purchased by credit buyers can be counted as positive cash flow. As a result, $630,000 must be decreased by the amount of sales that went to credit customers. As an aside, if our A/R balance had not changed from last period to this, we could safely assume that mathematically all of our sales had been for cash even though that possibility is extremely remote. More likely when the A/R balance doesn't change from one period to the next, the charge sales by our customers were exactly matched by their payments; while the total of A/R may have stayed the same, the mix of customers probably changed. Anyway, back to our example. Our credit customers' balances increased by $20,000, meaning that not all of the sales revenue can be counted as cash. By subtracting the $20,000 increase in A/R from the sales revenue, we arrive at the actual cash portion of the total Sales account balance. As cash received, the $610,000 with the positive (+) "tag" shows positive cash inflow, and our "tagging" system has clearly identified it as such. Plus, you didn't have to remember any textbook formulae! Cash payments for inventory: To determine cash flows associated with the purchase of inventory, let's examine the Cost of Goods Sold (CGS), Inventory, and Accounts Payable (A/P) accounts. For this examination, we will shorten the process somewhat. First, examine CGS from this period's income statement. By our previous definition and because CGS is an "expense of sales," its cash flow logic behaves like a "regular" expense account: the CGS balance starts at zero at period beginning and due to posted debits (if using the perpetual system) or because under the periodic system its value is calculated rather than an account balance, its ending balance is "contra" to the Sales account. So whatever value it is by period end, and no matter the type of costing system used (perpetual or periodic), CGS is always negative cash flow. Regardless of its value, always "tag" CGS with a negative cash flow suffix thus: $320,000 Next, examine the change in the Inventory account from the prior period: it increased by $14,000 from $75,000 to $89,000; since non-Cash asset account increases are debits and debits are negative cash flows, "tag" the absolute difference of $14,000 with a negative cash flow suffix thus: $14,000 – Finally, examine the change in A/P from the previous accounting period: A/P decreased by $5,000 from $50,000 to $45,000, and from the Additional Information all A/P balances were caused by inventory purchases; A/P is a liability account; liability decreases are debits; and debits are negative cash flows. "Tag" the absolute difference of $5,000 with a negative cash flow suffix thus: $5,000 Arrange these three amounts vertically with their cash flow "tag" suffixes and algebraically add them being mathematically mindful of their suffix "tags": $320,000 14,000 5,000 $339,000 - CGS expense Inventory balance change A/P balance change cash payments for inventory The result is $339,000 negative cash flow. Ask yourself if this calculation makes "cash flow sense." You'll find that it does. Cash paid by the business for buying inventory that is sold (CGS) will always be negative cash flow modified by changes in the Inventory and A/P accounts. Let's continue with cash flows associated with other types of expenses. Cash payments for salaries and other operating expenses: To determine cash flows from the payment of salaries and other operating expenses, examine all operating expenses, prepaid expenses, and accrued liabilities. By definition all operating expenses are negative cash flows, so "tag" total operating expenses with a negative cash flow suffix: $220,000 -. Next, examine the change in the prepaid expenses (using Prepaid Insurance herein as an example) from last accounting period to this period: Prepaid Insurance increased from $10,000 to $12,000 and it was not financed by increases in A/P per the given Additional Information; all prepaids are non-Cash asset accounts; increases to non-Cash assets are debits; and debits are negative cash flows. "Tag" the $2,000 increase in the prepaids with a negative cash flow suffix: $2,000 -. Finally, examine any accrued liabilities (e.g., Salaries Payable) for increases (cash flow positives) or decreases (cash flow negatives), and "tag" them appropriately. In our example, there are no accrued liabilities associated with this category, so array the two "tagged" amounts here and algebraically add them using their suffix "tags" to find $222,000 negative cash flow associated with payments for operating expenses. $220,000 - operating expenses 2,000 - Prepaid Insurance balance change $222,000 - operating expenses cash flow Cash payments for interest and taxes: To determine cash flows associated with interest and taxes, let's examine interest expense and interest payable and then income tax expense and income tax payable. First, calculate cash flows for interest. Interest expense from the income statement is defined as a cash flow negative because it's an expense debit, and because there was no discount or premium amortization on the bonds payable, "tag" the $6,000 with a negative suffix: $6,000 -. The Interest Payable account balance decreased by $1,000 from $9,000 to $8,000. Because the Interest Payable account is a liability account and because its change was a decrease and because liability decreases are debits and because debits are negative cash flows, "tag" the absolute difference of $1,000 with a negative suffix: $1,000 -. Algebraically add the two “tagged” amounts: $6,000 - interest expense 1,000 - Interest Payable balance change $7,000 - cash flow for interest Now calculate the cash flow for income tax expense. Income tax expense is an expense debit and cash flow negative, so "tag" it: $17,000 -. Examine the change in the Income Tax Payable account next: The account's balance increased by $10,000 from $15,000 to $25,000; liability accounts increase with credits and credits are positive cash flows. "Tag" the absolute difference of $10,000 with a positive cash flow suffix: $10,000 +. Algebraically add them, mindful of their suffix "tags": $17,000 - Income tax expense 10,000 + Income Tax Payable balance change $ 7,000 - cash flow for income taxes Sale of plant assets: The cash received from any sale of plant assets will be, by definition, cash flow positive. Recall that a plant asset sale will decrease the balance in the Plant Asset account with a credit, but all of that credit will not necessarily be cash flow, because the asset's cash sale price must be considered. In our example, the Plant Asset contra account, Accumulated Depreciation - Plant Assets (herein referred to as A/D), was first adjusted to reflect depreciation expense up to the time of the sale. From the income statement, we know that $26,000 was the amount of the credit to A/D and the amount of the debit to Depreciation Expense for the accounting period. Remember though, that depreciation is a non-cash expense, so it will not figure into the cash flow positives or negatives. However, knowledge of how depreciation expense and A/D fit into a cash sale of a plant asset will help you calculate, in many instances, the amount of cash received from plant asset sales. While it is the cash received in the sale that we are most concerned about, we must also be aware of the sale transaction's effect on the other related accounts. Continuing on with the example, after the A/D credit of $26,000 is posted, the A/D associated with only the sold asset is withdrawn from the A/D account resulting in a $14,000 debit to A/D (from the Additional Information). Notice also that you could have calculated the $14,000 debit to A/D by knowing what the beginning and ending A/D balances were and by finding the $26,000 amount of the depreciation expense in the income statement. With a beginning A/D balance of $52,000, a depreciation charge of $26,000, and an ending A/D balance of $64,000, the debit to remove the sold asset's associated A/D must have been $14,000. With this information, I suggest using a journal entry format to determine other missing information: You know from the Additional Information that the sold plant asset cost $40,000 and should be removed from the Plant Asset account with a credit. You also know that there must be a debit to A/D for $14,000. Right now, with a debit of $14,000 and a credit of $40,000 we are short by $18,000 on the debit side, and $4,000 of the shortage is the amount of the loss (known from the Additional Information). For most problems of this type you will be given enough information to determine either the cash received (the sale price) OR the amount of the gain or loss. Array what you know in journal entry format and then solve for the unknown element: Date A/D - Plant Assets (given) Cash (received) Loss (given) Sold Plant Assets (given) 14,000 (unknown) 4,000 40,000 The cash received must be $22,000 to balance with the remainder of the entry. If the cash amount is given but not the loss or gain, you can compute the unknown amount by using a similar type of journal entry format. Once the amount is known, "tag" it with the appropriate suffix for insertion into the statement of cash flows: $22,000 + Cash received from plant asset sale and we also "tag" the payment for the purchase of plant assets given in the Additional Information: $20,000 - cash purchase of plant assets net of bonds payable Cash payments to retire bonds payable: Calculation of cash flows for bond retirements is similar to that of Depreciation, A/D, and the sale of plant assets. They're similar because frequently the cash paid isn’t given and you must analyze the associated accounts to determine it. Again, I suggest using the journal entry approach used in the depreciation problem above. Examine the Bonds Payable account balances to determine that to have a balance of $96,000 after a beginning balance of $78,000 and an issuance of $65,000 for plant assets (given in the Additional Information), there must have been a retirement of $47,000 in bonds payable. Then look at the income statement to find any gain or loss on the transaction. In this example, you know from the income statement that there was a gain of $18,000. Use the journal entry format to solve for the unknown element: Date Bonds Payable Cash (paid) Gain (from income statement) 47,000 (unknown) 18,000 With this journal format it's easy to see that the cash paid must be $29,000 to balance the entry. Most problems of this type ask for solving the cash paid because the income statement carries the gain or loss on the retirement of the bonds. $29,000 - Retired bonds payable Cash received from sale of common stock: Almost always you can determine if stock was sold or bought during the accounting period by examining the contributed equity section of the balance sheets. In our example, the Common Stock account increased by $25,000. By our previous definition, we know that equity account increases are credits and credits are positive cash flows. So the $25,000 increase in the account will be "tagged" with a positive cash flow suffix: $25,000 + cash flow received from sale of common stock Cash payments for paying dividends: This calculation involves examination of the Retained Earnings account. Analyze the account to determine what the debit must have been if you are given a beginning balance, an ending balance, and a net income (or loss). In our example, with a beginning balance of $58,000 and a net income of $55,000 and an ending balance of $99,000, the debit required to achieve that ending balance must be $14,000. $14,000 is therefore the amount of the dividends paid in cash and it should be "tagged" with a negative cash flow suffix thus: $14,000 -. $14,000 - cash flow from dividends A question comes to mind here regarding dividends declared but unpaid. With dividends payable, the Retained Earnings account is still debited, so you might be tempted to count the debit as negative cash flow. However, dividends payable will also result in the creation of a liability as well as decreasing the Retained Earnings account. Therefore the negative cash flow debit to Retained Earnings and the positive cash flow credit to Dividends Payable cancel each other and result in zero actual cash flow. This conclusion also passes the "makes sense" test because when a dividend is payable and has not yet been paid, no cash has left the business. __________________________________________________________ Part III - Building the Statement of Cash Flows Once the cash flows have been determined for each of the operations, investing, and financing categories, it's a relatively simple matter to construct the statement of cash flows. You will also find that the "tagging" method works equally well with building a statement of cash flows using the "indirect method," which is shown after the "direct method" immediately below. Printer's Inc. Statement of Cash Flows (Direct Method) For The Year Ended December 31, 20X3 Cash flows from operating activities: Cash received from customers Cash paid for inventory Cash paid for salaries and other operating expenses Cash paid for interest Cash paid for taxes Net cash from operating activities Cash flows from investing activities: Cash received from sale of plant assets Cash paid for purchase of plant assets Net cash from investing activities Cash flows from financing activities: Cash received from issuing stock Cash paid to retire bonds Cash paid for dividends Net cash from financing activities Net increase(or decrease) in cash Cash balance at beginning of 20X3 Cash balance at end of 20X3 $610,000 (339,000) (222,000) (7,000) (7,000) $35,000 $22,000 (20,000) 2,000 $25,000 (29,000) (14,000) (18,000) $19,000 17,000 $36,000 Indirect Method The indirect method uses a format that differs from the direct method only in the section where net cash provided or used by operating activities is calculated. The investing and financing sections of the statement of cash flows are exactly the same under either method. When we use the indirect method to determine cash flows, we start with the net income figure from the income statement and adjust the net income amount to determine the net amount of cash provided or used in operating activities. The adjustments to net income are not journalized but are added to or subtracted from the net income amount because we want to eliminate those amounts included in calculating net income which are not a part of operating cash flows during the accounting period and we want to include operating cash flows that were not recorded as revenues and expenses. In other words, we are reconciling the accrual method of accounting to the cash basis of accounting. We also examine the changes in current assets and current liabilities to complete our calculation of operational cash flows. Using the same income statement, balance sheets, and Additional Information as we used in the direct method, let's construct a statement of cash flows using the indirect method: Printer's Inc. Statement of Cash Flows (Indirect Method) For The Year Ended December 31, 20X3 Net income Adjustments to reconcile net income to net cash from operating activities: Depreciation expense Loss on sale of plant assets Gain on retirement of bonds Change in Accounts Receivable Change in Inventory Change in Prepaid Insurance Change in Accounts Payable Change in Interest Payable Change in Income Tax Payable Total adjustments Net cash from operating activities Cash flows from investing activities: Cash from sale of plant assets Cash paid for plant assets Net cash from investing activities Cash flows from financing activities: Cash received from issuing stock Cash paid to retire bonds Cash paid for dividends Net cash from financing activities Net increase(or decrease) in cash Cash balance at beginning of 20X3 Cash balance at end of 20X3 Note that in sale of plant assets these three items are accrual net income by $55,000 $26,000 4,000 (18,000) (20,000) (14,000) (2,000) (5,000) (1,000) 10,000 (20,000) $35,000 $22,000 (20,000) 2,000 $25,000 (29,000) (14,000) (18,000) $19,000 17,000 $36,000 the operations section we add back depreciation expense and the loss on the but we subtract the gain on the bond retirement. We do so because although used to determine net income, they are non-Cash amounts and we must modify our these amounts to properly calculate the cash flows from operations. Note also that in both the direct and indirect methods the different amounts carry their "tagged" suffixes into the statements of cash flows. For example, in the direct method, we had a positive "tag" on the $610,000 received from customers, and you'll find that positive amount in the statement of cash flows. We also had "tagged" $319,000 as a negative sum when we calculated cash flow for cash-paid inventory purchased. In the indirect method statement, note that the change in A/R was a negative $20,000 cash flow, just as we had "tagged" it when we analyzed the account and discovered that the A/R balance had grown by $20,000 from one year to the next. In summary, then, one of the very useful qualities about the "tagging" method is that if you carry the suffix along with the amount, you'll always know whether it will be positive or negative cash flow when you place the amount in the statement of cash flows. Note that the schedule of non-cash investing and financing activities is excluded from presentation from both the direct and the indirect methods herein since it is not a mathematical approach to determining cash flows from the two balance sheets and the connecting income statement. __________________________________________________________ Part IV - Final Thoughts I call this method of cash flow analysis what I do because it was the thought process I developed so that I could pass my financial accounting course. Before I developed the method I had never seen it in print anywhere, nor have I since, so I claim the title and method. I understand that you may not be comfortable with it and you may prefer to use another method of learning cash flow calculations. That's all well and good, and in fact I don't mind if you do. However, I know my method works for students who choose to use it. For me, it was an easy way to memorize what I needed to know for testing purposes. Additionally, I find its use so easy from the outset that I have completely discarded the traditional textbook method. And I can truthfully tell you that from a teaching perspective it continues to allow me the luxury of not having to memorize textbook formulae so that I can discuss it with you in the classroom. Its beauty is its simplicity. __________________________________________________________ Part V – End Notes Earlier in Part I, we modified the Accounting Equation to be: Cash = Liabilities + Equity - Non-Cash Assets If we take only the beginning and ending balance sheets and analyze the changes in the non-Cash asset, liability, and equity accounts, we can determine the change in the Cash account. In the balance sheets, the liabilities increased $22,000, the equity accounts increased $66,000, and the non-Cash asset accounts increased $69,000. Plugged into the modified Accounting Equation, we get: Cash = $22,000 + $66,000 - $69,000 Cash = $19,000 and $19,000 is the positive amount of the Cash account increase. This solution gives us the total of the Cash account changes but it doesn’t give us the categories we need of operations, investing, and financing. That’s why we use the income statement to link the two period balance sheets.