Chapter 1: Introduction to the Food and Policy System and the

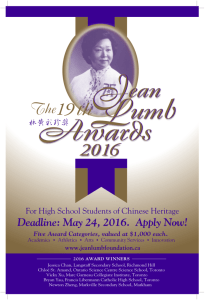

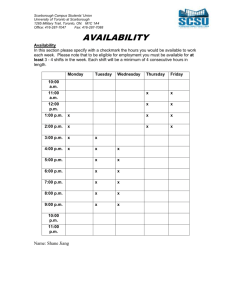

advertisement