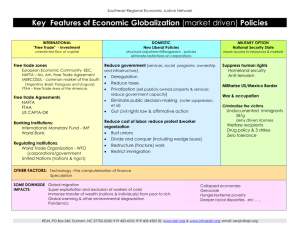

Taxation, Non-Discrimination and International Trade in Services

advertisement