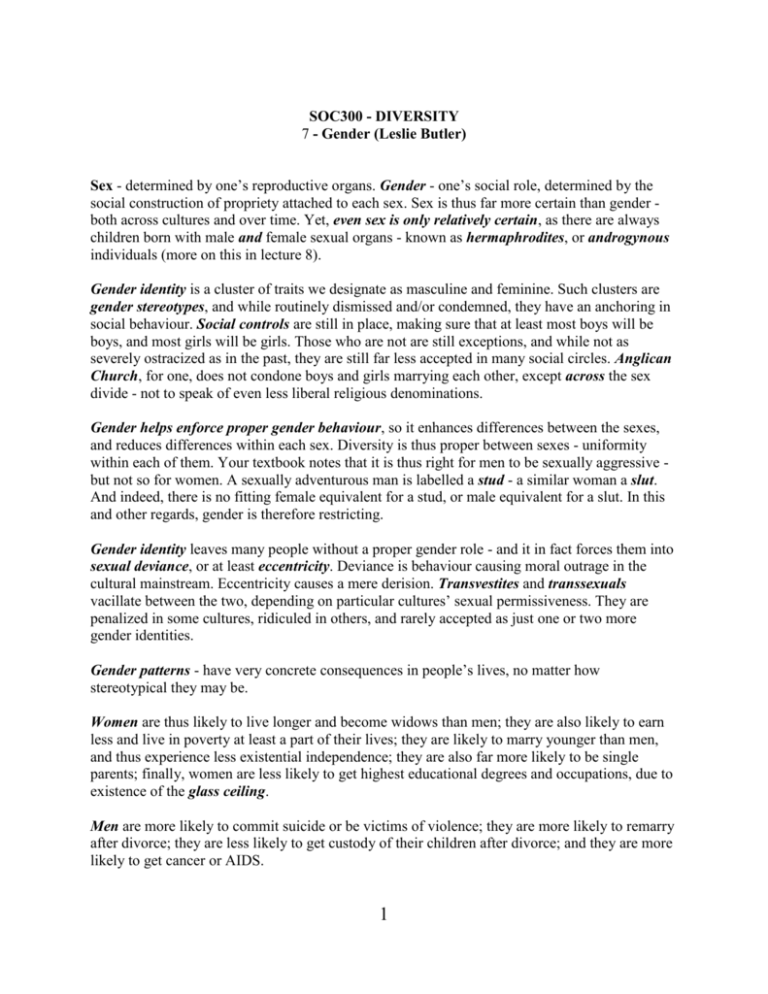

SOC300 - DIVERSITY

7 - Gender (Leslie Butler)

Sex - determined by one’s reproductive organs. Gender - one’s social role, determined by the

social construction of propriety attached to each sex. Sex is thus far more certain than gender both across cultures and over time. Yet, even sex is only relatively certain, as there are always

children born with male and female sexual organs - known as hermaphrodites, or androgynous

individuals (more on this in lecture 8).

Gender identity is a cluster of traits we designate as masculine and feminine. Such clusters are

gender stereotypes, and while routinely dismissed and/or condemned, they have an anchoring in

social behaviour. Social controls are still in place, making sure that at least most boys will be

boys, and most girls will be girls. Those who are not are still exceptions, and while not as

severely ostracized as in the past, they are still far less accepted in many social circles. Anglican

Church, for one, does not condone boys and girls marrying each other, except across the sex

divide - not to speak of even less liberal religious denominations.

Gender helps enforce proper gender behaviour, so it enhances differences between the sexes,

and reduces differences within each sex. Diversity is thus proper between sexes - uniformity

within each of them. Your textbook notes that it is thus right for men to be sexually aggressive but not so for women. A sexually adventurous man is labelled a stud - a similar woman a slut.

And indeed, there is no fitting female equivalent for a stud, or male equivalent for a slut. In this

and other regards, gender is therefore restricting.

Gender identity leaves many people without a proper gender role - and it in fact forces them into

sexual deviance, or at least eccentricity. Deviance is behaviour causing moral outrage in the

cultural mainstream. Eccentricity causes a mere derision. Transvestites and transsexuals

vacillate between the two, depending on particular cultures’ sexual permissiveness. They are

penalized in some cultures, ridiculed in others, and rarely accepted as just one or two more

gender identities.

Gender patterns - have very concrete consequences in people’s lives, no matter how

stereotypical they may be.

Women are thus likely to live longer and become widows than men; they are also likely to earn

less and live in poverty at least a part of their lives; they are likely to marry younger than men,

and thus experience less existential independence; they are also far more likely to be single

parents; finally, women are less likely to get highest educational degrees and occupations, due to

existence of the glass ceiling.

Men are more likely to commit suicide or be victims of violence; they are more likely to remarry

after divorce; they are less likely to get custody of their children after divorce; and they are more

likely to get cancer or AIDS.

1

Gender spheres - refer to patterns of female and male behaviour which affect people’s work,

education and leisure. Women predominate in traditionally ‘female’ or ‘caring’ occupations like

nursing, social work, teaching, services and clerical work - creating a female occupational

sphere.

Men predominate in technology, administration, professions and manual labour - creating a male

occupational sphere. These spheres are supported by the existence of educational spheres,

where women enroll in programs training people for the above ‘female’ occupations more than

men, and men enroll in ‘male’ occupations programs more often than women.

Leisure spheres are also gendered. There are female leisure spheres and male leisure spheres.

The former include swimming, cross-country skiing, fitness clubs, yoga practices and bowling.

The latter range from football and hockey, to hunting and working out. This does not imply a

strict gender separation, but it does mean that a degree of such separation exists.

The existence of gender spheres raises the issue of equality. Namely, are men and women

different but equal, or different and unequal? The answer is that they are different and unequal:

in pay, in occupational achievements, or in the amount of housework they do. Men are unequal

in terms of child custody at divorce (courts give children’s custody to women ten times more

often than to men), they spend more hours working for pay, and they are more likely to fall prey

to occupational hazzards associated with stress.

Sexual politics - your textbook argues that women have a degree of power over men when it

comes to sexual exchanges, due to an apparently greater sexual appetite of men. This is why

female prostitutes and fashion models can earn more than their male colleagues. So, do women

have a degree of sexual power over men, or is this a cultural myth?

Progressivism and conservatism in gender analyses - often identified with nurture vs. nature

debates. To argue that human behaviour is socially constructed (nurtured), at least implies that it

is malleable, and ultimately improvable, if you wish. To argue that human behaviour is

biologically determined at least implies that it is perennial, and that we are stuck with it.

Theories of gender spheres - structural functionalists argue that the roles women and men play

in society are natural, and that they help society run and maintain itself with the least degree of

friction. Exclusion of women from workforce was deemed justifiable on the grounds that it

increases the chance for each family to have some earned income. Gender spheres thus help

reduce conflict in society. Conflict theorists argue that gender spheres within which women are

payed less than men, and men are forced to compete for jobs against cheaper female labour

ultimately benefit employers - managers and capitalists - who are ever more often women.

Conversely, feminist conflict theorists argue that gender spheres help maintain male domination

over women.

Meritocracy vs. social connections - the idea of meritocracy, or dominance of the most

deserving members of society is firmly defended by structural functionalism, and made famous

2

by Davis and Moore. In the area of gender, this would mean that men have higher earnings,

more property and political power because they work harder to gain them - or that they are more

capable. The critics of meritocracy argue that women are prevented from achieving more by

systemic barriers - such as the laws barring them from combat; hiring criteria demanding certain

strength or height; or cultural messages relaying that some jobs are for men, others for women.

Individual choice - all the above cautions us that we are not free to pursue our life choices at

will, but that such choices are often made for us by the nature of our gender spheres.

3