lincoln christian seminary

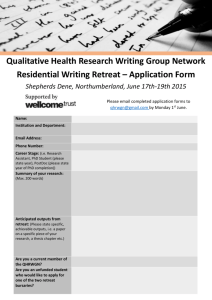

advertisement