restatement of the doctrine of piercing

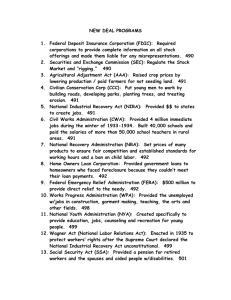

advertisement