AP Art History - Ohio County Schools

advertisement

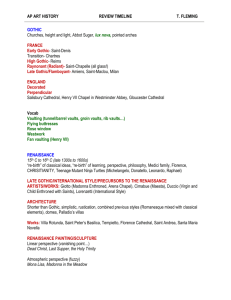

AP Art History AP Art History covers approximately 30,000 years of art creation, from the Prehistoric and Neolithic periods to 20th Century, Postmodern and current art trends. Though a brief survey of Asian, African and other Eastern Art is studied, the bulk of this year-long class covers mainly Europe and the rest of the Western World. The course studies historical transition of art periods, as well as how culture, religion, government and history reflect the personal and sociological art trends throughout the existence of humans. [C1] Texts Primary Text: Marilyn Stokstad’s Art: A Brief History. Prentice-Hall, 3rd Edition. Supplemental Texts: Helen Gardner’s Art Through the Ages. De la Croix and Tansey, 12th Edition. Carol Strickland’s The Annotated Mona Lisa: A Crash Course in Art History from Prehistoric to Post-Modern. Andrews and McMeel, 1992. Teaching Strategies: Throughout the year, each section or chapter will begin with a student reading assignment (usually a whole chapter, or half depending on the subject. Classroom discussions and lectures are based on PowerPoint presentations. Normally the day or two before test is spent reviewing these pieces of Art from the PowerPoints. Assessments: C1 – The syllabus is organized to include course content material from the ancient world through the 21st century. Topics Taught Include: First Semester: Introduction to Art and Prehistoric to High Renaissance. Second Semester: Baroque and Rococo to Present. Most tests for this class are based on three parts: Slide identification: Identify fifteen to twenty pieces including the name, artist (if applicable), approximate year and period. Multiple Choice: The format for this section runs parallel to the AP Test, where several of the questions are based on works shown directly on the test. Approximately 30-40 multiple choice questions make up a test. Written Response: Short-essay questions often compare and contrast two periods, artworks or cultures. Non-Western art is included as part of the essay when applicable. This essay accounts for about fifteen to twenty percent of the test. Week I and II: Introduction and Prehistoric Art [C1] During this section, students will learn basic aesthetic terminology (such as the principles or Art), and discuss the philosophies of what makes good art. Students will explore events or cultural conditions that can affect the way art is made, such as technology, war, government, politics and religion. [C2] To begin exploring art history, students will study the Prehistoric and Neolithic periods, and discuss the purpose of creating such items like cave paintings, the Woman of Willendorf or Stonehenge. Reading: Introduction and Chapter 1 of the primary text. Week III: Ancient Near Eastern Art Students will see the birth of civilizations and how the conquering of lands affected the change in the art of those regions. A good mneumonic used in class is, “Some Apples, Bananas And Peaches” to remember the five basic periods from this section: Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian and C2 – The course teaches students to understand works of art within their historical context by examining issues such as politics, religion, patronage, gender, function and ethnicity. The course also teaches students visual analysis of works of art. The course teaches students to understand works of art through both contextual and visual analysis. Persian (Neo-Sumerian and Neo-Babylonian are included in this section.) Influences of geography, politics (hieratic scale) and religion are heavily discussed in this week. [C3] C3 – Roughly 20 percent of this course is devoted to art beyond the European tradition. Reading: Excerpts from Epic of Gilgamesh and Hammurabi’s Code, and the first half of Chapter 2 (pgs. 37-47). Test: Prehistoric and Ancient Near East. Week IV: Egyptian Art This section will see the merging of Upper and Lower Egypt into an Empire, comparing and contrasting its religion and politics to those studied from the Near East. Examples of both sculpture and architecture from Old, Middle and New Kingdom are presented, with emphasis on the stylistic changes during Akhenaton’s Amarna Period. Styles of full figure sculpture are also highlighted. Reading: Second half of Chapter 2 (pgs. 48-61) Test: Old, Middle and New Kingdom Egyptian Art Week V: Aegean & Greek Art Emphasis is placed on Cycladic, Minoan and Mycenaean cultures. With the development of major palaces, fortresses and tombs, students will be able to explain how geography and location of a culture (be it inland, coastal or island) affects its art and architecture. It is also noteworthy to contrast the differences between the Minoan and Mycenaean civilizations. The second half of this unit shows the development from Archaic and Geometric Greek products to the establishment of a mature Early, High and Late Classical Greek environment. The unit will begin to explain Greek philosophy and how it influences sculpture and figure vases. The unit will conclude with discussing the relationship between a city-state plan and how landscape affects the placement of buildings. Reading: Chapter 4 of the primary text, and “What is Art”, written by Plato. Week VI: The Spread of Greek Culture C2 – The course teaches students to understand Week Six not only shows the development of an emotional Hellenistic style, but explores how the styles of the Greek culture spread across other Mediterranean and Near East Cultures. [C2] Reading: Chapter 5 in the primary text. Test: Aegean, Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic Greek Art. Week VII: Roman Art Teaching Roman Art deals with several important aspects: How political propaganda is used through art; How structure and organization led to the development of a Roman Empire; and How the conquering of the Greeks led to an insatiable appetite for Classical Greek imitation. The students will compare and contrast the relationship of Roman architecture to that of the Greeks. What elements did the Romans add to an already scientific set of architectural and sculptural rules? [C2] The class will discuss the development of Etruscan Art and how its style changed the perception of house and sarcophagus design. Reading: Chapter 6 in the primary text. Test: Roman and Etruscan Art Week VIII: Early Christian, Jewish and Byzantine Art This section begins around the birth of Christ (featuring Jewish prayer houses) to the Edict of Milan by Constantine, allowing religious freedom and legalizing Christianity. works of art within their historical context by examining issues such as politics, religion, patronage, gender, function and ethnicity. The course also teaches students visual analysis of works of art. The course teaches students to understand works of art through both contextual and visual analysis. This chapter shows the movement of mosaics from Roman houses and civic centers to use as religious illustrations, such as the Good Shepherd. It begins identifying specific figures in mosaics, and explain how the Church and State were merged together as one entity. C3 – Roughly 20 percent of this course is devoted to art beyond the European tradition. It is also important to note the change of the Roman basilica as a government building to a house of worship. The students should explain the differences between a basilica plan such as Santa Sabina to a central plan like Hagia Sophia. [C3] Discuss how the Iconoclasm creates a ‘Dark Age’ for art and culture. Reading: Chapter 7 of the primary text. Test: Early Christian, Jewish and Byzantine Art Week IX: Early Medieval Art in Europe This chapter gives a deeper look into how religion and the rituals that follow influence the architectural design of Christian Churches and Islamic Mosques. For example, the students explore the differences in the Hagia Sophia before and after the invasion of the Ottoman Turks in 1453. [C3] Students will see the development of manuscript illumination, as well as the inclusion of Hiberno- and Anglo-Saxon tribal work, such as understanding how uncovering burial ships full of art validate literary works like Beowulf. This chapter also explains how the Carolingian and Ottonian Empires affected the layout of the Christian Church, and the reemergence of sculptural works with the Church, such as Bishop Bernward’s doors. Reading: First half of Chapter 10 of the primary text (up to pg. 256), and excerpts from Beowulf. Week X: Romanesque Art As technology increases to make for better roads and travel, pilgrimages greatly affect the planning and layout of Christian Churches (such as ambulatories), as well the position of the C3 – Roughly 20 percent of this course is devoted to art beyond the European tradition. Medieval Church and royalty. Students should be able to explain how the decorative tympanum (such as Gislebertus’ Last Judgment) is considered ‘sculptural religious propaganda’, and describe the terms associated with a three-story elevation of a Romanesque church: nave, gallery, clerestory. Reading: Second half of Chapter 10 (pgs. 256-271). Test: Early Medieval and Romanesque Art. Week XI: Gothic Art The development of both French style and a more ‘spiritual design’ led to the rise of the University, Scholasticism and Gothic Architecture. Students will examine how the spirituality and academia of the French differ or compare to that of the Greeks. It is imperative that students see the very different styles between that of Romanesque and Gothic. This chapter will focus on building styles of Early, High and Late Gothic, as well as to distinguish between French and English Gothic. (It is also helpful to distinguish between English Decorated and English Perpendicular Gothic.) Students should see the relationship between Gothic cathedrals and sculpture (such as the Royal Portal). Video: History Channel’s Modern Marvels: Gothic Cathedrals. Reading: First half of Chapter 11 of the primary text. Week XII: Gothic Painting (ProtoRenaissance) Students will learn how the Gothic era influenced early 14th century Italian artists such as Duccio, Cimabue, Giotto and the Lorenzetti Brothers. Students will see how the Greca Mannera (‘Greek Manner’) style developed, along with the new technique of modeling figures with lights and shadows. The class should be able to see which of these techniques is ‘new’ (Renaissance) and which are still Gothic. Students willlook at Giotto’s Arena Chapel and discuss how painting and architecture emerge as one whole piece. The class will read excerpts of Vasari’s Lives of the Artists and see how a Renaissance writer views these same pieces. Reading: Second half of Chapter 11 (pgs. 295-303) of the primary text. Test: Gothic Architecture and Painting (Late Gothic) Week XII: Early Renaissance Art (Outside of Italy) The class will examine the Burgundian style and the International Style (as seen in the Limbourgh Brothers’ Tres Riches Heures). How is this style of painting different than that considered Late Gothic? The students should see the beginnings of the triptych altarpiece, and the importance of private donors for Flemish Church altarpieces (such as the Merode Altarpiece or Ghent Altarpiece) and compare those with the frescoes by Massacio in the Branacci Chapel. This chapter will explore the extremely detailed work of the Flemish artists like Van Eyck, Van der Weyden and Petrus Christus. Reading: First half of Chapter 12 (pgs. 305-318) in the primary text. Week XIV: Early Renaissance Art (Italy) The birth of new ideas spreads across Italy, yet many artists still pay homage to Classical art. One good comparison is Fra Angelico’s Annunciation to Jan Van Eyck’s painting of the same name. [C2] This chapter will show how wealthy patrons (such as the Medicis) affected the collection of art. Students will compare that to the patronage of specific altarpieces in the North. C2 – The course teaches students to understand works of art within their historical context by examining issues such as politics, religion, patronage, gender, function and ethnicity. The course also teaches students visual analysis of works of art. The course teaches students to understand works of art through both contextual and visual analysis. Reading: Second half of Chapter 12 in the primary text. Test: Early Northern and Italian Renaissance. Week XV: Renaissance Art in Italy The class will look at the definition of ‘Renaissance Man’ and see the importance of architecture, painting and sculpture becoming one, especially within the same group of artists. One such example is Michelangelo’s David, Ceiling of Sistine Chapel and layout for St. Peter’s. The students will see the relationship between artist and patron, such as Raphael and the Stanza Della Segnatura or Michelangelo and Pope Julius II. Students will explore why some artists like Tintoretto and Pontormo decided to forgo the Classical painting technique to pursue a distorted, emotional “Mannerist” style of painting. Based on this style, debate whether Spanish artist El Greco should be considered ‘Mannerist’ or ‘High Spanish Renaissance’. Reading: First half of Chapter 13 in the primary text. Week XVI: Renaissance Art in the North As the Northern Countries begin the Reformation, artists begin to exhibit their own styles as painters like Bosch, Bruegel, Durer, Altdorfer, Holbein and Grunewald personalize their art. Students will compare the style of Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece to an altarpiece by an earlier Flemish artist. [C2] See how artists like Pieter Bruegel the Elder was one of the first to use peasants as his main subject matter, not just including them in a religious scene. Reading: Second half of Chapter 14 in the primary text. Test: High Northern and Italian Renaissance. Week XVII & XVIII: Baroque Art Contrary to many of the cultures already studied, the Baroque C2 – The course teaches students to understand works of art within their historical context by examining issues such as politics, religion, patronage, gender, function and ethnicity. The course also teaches students visual analysis of works of art. The course teaches students to understand works of art through both contextual and visual analysis. period covers styles that span across Italy, France, Spain, Flanders and the Netherlands. Each country had their own goals, techniques and styles depending on the location, government, economy and religion. Students will learn how the power of the Counter-Reformation in Italy changed the dynamics of painting, architecture and sculpture, while the lack of a strong government (and a strict Protestant society) in the Dutch Republic made for many nonreligious works. Compare how Dutch painters like Jacob Ruisdael made a living doing landscapes, while French Baroque artists like Claude Lorrain compromised his landscapes with a nod to Classical elements. Using Rubens, Van Dyck and Velazquez as examples, students will see how artists made their living as court painters who attempt to paint their patrons in a slightly unrealistic light of nobility. When studying French Baroque, the class will look at the evolution of Rococo and contrast the styles between a Baroque painter like Poussin and a Rococo painter like Watteau. Students will investigate the general view of life in France as opposed to those living in the Netherlands. Reading: Chapter 14 of the primary text. Test: Baroque Art Week XIX & XX: Neoclassicism, Romanticism & Realism Students study the widespread popularity of the Classical movement throughout France, and its impact on the art during the French revolution. Students will see how these conservative yet free-thinking ideas created the beginning of American art in the 1770’s. French artists David and his former pupil Ingres are studied closely, as well as American artists Copley, Stuart, West and even Thomas Jefferson’s architectural work. In England, the class looks into the life of the upper class through the works of Hogarth, Reynolds and Gainsborough. In contrast, the Romantic period is then examined, not only as a comparison and contrast from the Neoclassical period, but how this loose style affected the study of landscapes. English artists like Turner and Constable are analyzed against each other, as are several of the Hudson River School artists (Cole, Church, Bierstadt, Duncanson and Durand.) The introduction of photography is very important in this chapter, as it officially begins the distinct separation of ‘naturalism’ in art versus ‘realism’. Reading: Chapter 17 of the primary text. Test: Neoclassicism, Romanticism and Realism. Week XXI & XXII: Late Nineteenth-Century Art in Europe and the U.S. This chapter begins with the study of Manet, who has been credited with being one of the forefathers of Impressionism. Many consider his work different from the Impressionists. If so, how was he an influence, and how was he different? In general, the students will study the art of the Impressionists and learn why the study of light and color created a new way of painting. Lives of Post-Impressionists artists are also taught in this section, as these artists created a unique style either based on visual technique (like Seurat and Cezanne) or more emotional colors (like Gauguin and Van Gogh.) Students will learn about the significance of the Eiffel Tower’s opening in 1889 and how the use of cast iron dramatically changed architecture and structure. Reading: Chapter 18 of the primary text. Video: A&E Biography on Vincent Van Gogh. Test: Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Architecture in the late 1800s. Week XXIII & XXIV: Modern Art in the Early 20th Century Never in art history has the ‘tree of art’ branched out into so many different styles, theories and techniques than in the first forty years of the 1900s. From the Expressionists, like The Fauves, to Die Brucke, Cubism, Dada, Surrealism and Constructivism, the class delves into the various ‘roles’ in art: The role of the artist in society The role art has as a communication device and in context The role of subject matter (or lack thereof) in art This chapter discusses art in its response to war, such as the Dadaist reaction to World War I. This section also examines architecture and its attempt to balance good function with radical aesthetics. Examples of this include Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie Style, De Stijl and the introduction of Walter Gropius and the Bauhaus movement. The class will see how the influence of African masks influenced and inspired the movement that became Cubism. [C3] Reading: Chapter 19 of the primary text. Test: Expressionism, Die Brucke, Cubism, Dada, Surrealism and Constructivism. Week XXV & XXVI: Art after 1945 In this chapter, we begin to see art styles that are truly American, with little or no European influence. Much of the style of painting is primarily that of the Abstract Expressionists and Color field painters. Does art need to have subject matter or a message to be considered art? Can aesthetics by itself, namely colors and shapes, void of subject matter, still be considered art? Students discuss their original philosophies of art from the beginning of C3 – Roughly 20 percent of this course is devoted to art beyond the European tradition. the school year and see if their writings still hold true after surveying over 25,000 years of art. Pop Art, the antithesis of Abstract Expressionism, also emerges in the late 1950s through the 1960s. Students will study how American commercialization affects the art around. Also included in this section are Photorealism, Earthworks / Land Art and Conceptual / Performance Art. Reading: Chapter 19 of the primary text. Test: Art after 1945. Week XXVII: Independent Study of Non-European Culture Due to an AP Curriculum is at least 2 weeks shorter than most, our class is forced to condense the amount of time spent on Non-Western cultures. To accommodate for this, students choose one particular area of Non-Western Culture (not studied previously in class) and become an expert at it. Students will then give a 15-minute presentation using PowerPoint (and handouts) that includes the region, styles, techniques, etc. Students must also find a Western connection to this artwork. To finish, students must create a 15-20 question test over their culture to give to the class. Among the possible cultures to choose from include: Hindu, African, Chinese / Buddhist, Japanese / Pacific Rim, and Islamic. Week XXVIII: Getting Ready for the Test The last week before the test focuses more than ever on improving their AP essay writing. Now that all of the information has been covered, students will be given sample AP essays from the past as writing assignments. Using the rubrics in the AP handbook, the class will continue to learn what makes a good essay and how the readers score each essay.