How to Analyze a Poem

advertisement

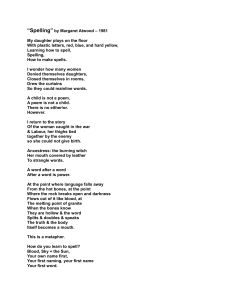

How to Analyze a Poem Instructions: Below, you will find the poem It is Dangerous to Read Newspapersby Margaret Atwood and an analysis of the poem. This is exactly what you will be doing when you analyze your poems. This is a sample of how to do the assignment. Here is what you do, step by step: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Read the poem. Underline all of the words that you don’t understand or think would have major significance. Look them up in the dictionary and write down the meaning. If there is a word or phrase that seems to have a particular connotation, write down the connotation or make a note to find out the connotation. Look up the author’s background. Find out when he/she wrote the poem. Are there references to the time period in the poem? If so, look up the time period. In this poem, the references to a typewriter, soldiers in flaming jungles, and bodies being bulldozed into pits are clear indications of the time period. Reread the poem. Write down what you think it means, now that you understand more about the author and time period. Go through the poem, looking for poetic devices. Underline them and categorize them as I’ve done in the sample, below. Now reread the poem again. Write down what you think it means, now that you understand more about the poetic devices. Reread your notes on the author’s bio and time period; reread your notes on the poetic devices; reread the poem. Now write your analysis. It is Dangerous to Read Newspapers by Margaret Atwood While I was building neat castles in the sandbox, the hasty pits were filling with bulldozed corpses and as I walked to the school washed and combed, my feet stepping on the cracks in the cement detonated red bombs. Now I am grownup and literate, and I sit in my chair as quietly as a fuse and the jungles are flaming, the underbrush is charged with soldiers, the names on the difficult maps go up in smoke. I am the cause, I am a stockpile of chemical toys, my body is a deadly gadget, I reach out in love, my hands are guns, my good intentions are completely lethal. Even my passive eyes transmute everything I look at to the pocked black and white of a war photo, how can I stop myself It is dangerous to read newspapers. Each time I hit a key on my electric typewriter, speaking of peaceful trees another village explodes. ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ It is Dangerous to Read Newspapers Analysis: Denotation: detonated: 1. to explode with suddenness and . to cause (something explosive) to explode. fuse: a tube, cord, or the like, filled or saturated with combustible matter, for igniting an explosive. charged: to fill or furnish (a thing) with the quantity, as of powder or fuel, that it is fitted to receive: to charge a musket. stockpile: a quantity, as of munitions or weapons, accumulated for possible future use lethal: of, pertaining to, or causing death; deadly; fatal: a lethal weapon; causing great harm or destruction. passive: not reacting visibly to something that might be expected to produce manifestations of an emotion or feeling; not participating readily or actively; inactive transmute: to change from one nature, substance, form, or condition into another; transform. Connotation: “the hasty pits were/filling with bulldozed corpses”: This is a reference to the Holocaust. We know this because Atwood was born in 1939 and the “hasty pits” were being filled when she was still young enough to be playing in a sandbox. We can deduce the time and historical event. “detonated red bombs”: This is a reference to the Cold War. “Red” is a reference to Communism. Atwood would have been in her early teens during this time. “the jungles are flaming, the under-brush is charged with soldiers”: This is a reference to the War in Vietnam. We can deduce this because the poem is written in 1968 and Vietnam had jungles set on fire by bombs.Poetic Devices: Alliteration: line 16: I am the cause … chemical toys line 24: white of a war Assonance: line 2: castles in the sandbox Consonance: line 6: washed and combed line 10: literate, and I sit Repetition: line 10: and literate, and I sit line 11: as quietly as a fuse Simile: line 11: as quietly as a fuse Metaphor: lines 12/13: the underbrush is charged with soldiers lines 16/17: I am a stockpile of chemical toys lines 17/18: my body is a deadly gadget line 19: my hands are guns Personification: line 22: my passive eyes Paradox: line 27: It is dangerous to read newspapers Written Analysis: If a poem is titled “It is Dangerous to Read Newspapers,” it seems only logical to determine what newspapers were reporting when that poem was written. What was Margaret Atwood reading in 1968? How could reading a newspaper possibly be dangerous? A simple Wikipedia search — something no one could have done when Atwood wrote the poem — shows the world was a very violent place in 1968. The War in Vietnam was raging with a series of military offensives and massacres. Newspapers were filled with gruesome images of the war and equally graphic images of student protesters being beaten for marching against it. There were riots in the streets, pictures of buildings being set afire, students being shot, and what looked like society falling apart. And, most shocking of all, there were two very high level assassinations: Presidential front-runner Bobby Kennedy and Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King. But Atwood does not start with this. She starts, instead, with herself in a sandbox. While she is creating castles in her sandbox, murdered Jews are being hastily buried in pits in Germany and Poland. This is a strange juxtaposition of images. Both show digging and activity, but one represents innocence and the other, evil. Why does she do this? She does it to shock us and pull us into the poem and she does it to give us a subtle message: Our whole lives, whether we are aware or not aware, there is suffering and evil and destruction. Even when we are oblivious as children, bad news still exists. The next stanza brings us further into her childhood and early teens. While children today might not know the expression, children in Atwood’s day were superstitiously careful when walking on sidewalks. “Step on a crack, break your mother’s back” was the rhyme every child knew. Only this time, it isn’t “step on a crack, break your mother’s back,” it’s “step on a crack, detonate a bomb.” The fear during the Cold War was of nuclear annihilation: the end of the world. Students in the early 1950‘s would have known about the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and they would have participated in the drills every school conducted, drills in which they heard an air raid siren and were told to huddle under their desks until the all clear was given. In the first two stanzas, Atwood is a child — in a sandbox and walking to school — and yet already the news of the world has infiltrated her life. Whether she was reading the newspapers or not, the bad news, the news that spoke of destroyed life and the potential destruction of the whole world, was out there every day. If the child Atwood felt she could control the world by being orderly or not stepping on cracks, the adult Atwood is not so naive. By now a grownup and literate, she sits in her chair “as quiet as a fuse.” This simile works in two ways: It shows her nervousness and fear, and it shows her complicity. A fuse is the thing that allows a bomb to explode. By “reaching out in love” and “having good intentions,” she hopes she can avoid adding to the violence in the world. If she is the fuse, perhaps her good behaviour can keep at least one bomb from being lit. Just as she tries to control her world as a child by being orderly and careful, she tries to control her world as an adult by being a good person. But it isn’t to be. When her “passive eyes” read the news, she isn’t responsible for it but she feels guilty and declares “I am the cause.” This is the same guilty feeling we have watching people on TV suffering in a famine. We don’t cause the suffering of others by having more but we feel guilty and spoiled, all the same. Atwood looks at the massacres in Vietnam (“the jungles are flaming, the underbrush is charged with soldiers”) and feels that by being safe in North America and just watching from afar, she is culpable. If her country is involved in the war and her country is sending soldiers to kill, then she is “completely lethal.” It doesn’t matter if she has good intentions or if she feels compassion, “(her) hands are guns.” Even when she tries to speak against the war, when she hits a key on her electric typewriter, “speaking of peaceful trees,” it is meaningless. She has no power to stop the war or to stop any of the ugliness she reads about in the newspaper. By the time she has typed a sentence, she knows another village will have exploded. By the time we reach the end of the poem, we realize she has made the same point she starts out with. When she was a child playing in her sandbox, unaware of the news of the day, atrocities were happening. Now, as an adult, no matter what she does — whether she is quiet and passive or involved and aware — the atrocities in the world will still occur. She cannot affect the events occurring in the world and she cannot be unaware. She cannot have the innocence she had in her childhood sandbox. Her “passive eyes” will “transmute” everything she looks at. If she looks at a sandbox now, she will see the dead bodies being shoveled into the pits. The images of the 20th century are part of her and she cannot “unsee” what she has seen. The news is part of who she is and how she sees the world. Her innocence is lost. In a sense, reading that first newspaper is like taking a bite of the apple: Dangerous. http://watsonpoetry.wordpress.com/how-to-analyze-a-poem/