Mawooshen-graphicsFinal-7-23

advertisement

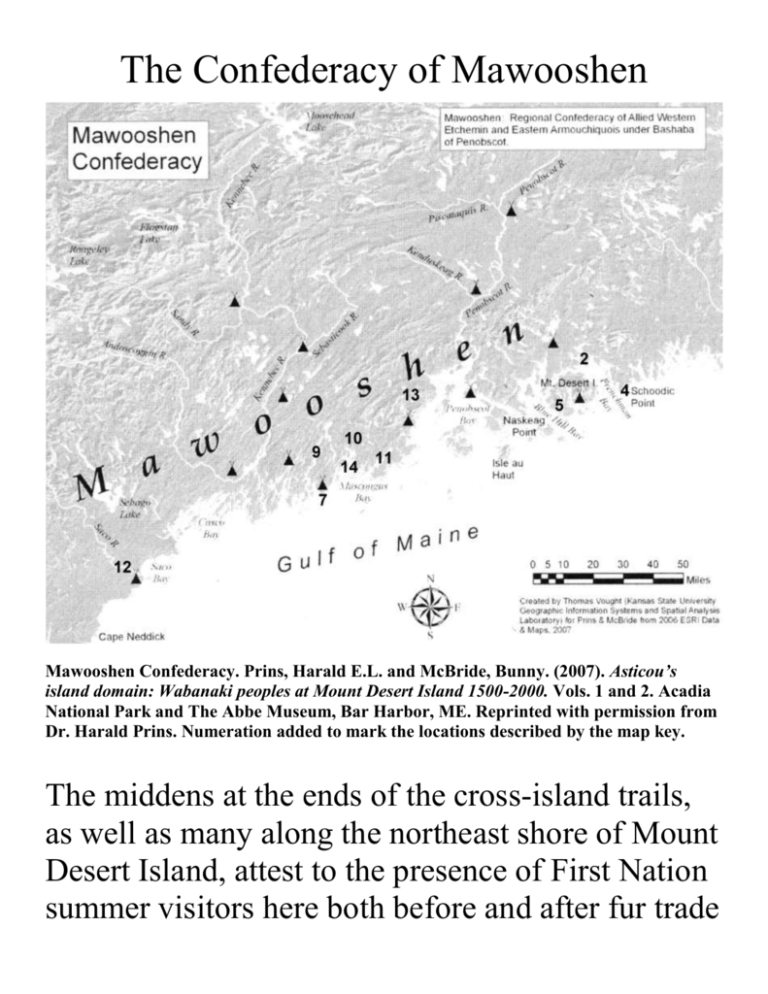

The Confederacy of Mawooshen Mawooshen Confederacy. Prins, Harald E.L. and McBride, Bunny. (2007). Asticou’s island domain: Wabanaki peoples at Mount Desert Island 1500-2000. Vols. 1 and 2. Acadia National Park and The Abbe Museum, Bar Harbor, ME. Reprinted with permission from Dr. Harald Prins. Numeration added to mark the locations described by the map key. The middens at the ends of the cross-island trails, as well as many along the northeast shore of Mount Desert Island, attest to the presence of First Nation summer visitors here both before and after fur trade related warfare and pandemics destroyed the Abenaki Confederacy of Mawooshen. This historical marker has been erected in memory of the First Nation communities of this Confederacy, also noted as Norumbega (10) on many maps, including Champlain’s shown below. Close-up of Champlain’s 1613 map from Norumbega Reconsidered (Brack 2010) fig. 8, pg. A-12. The Breakneck Hollow and Mt. Desert Island lie in the eastern region of the Confederacy of Mawooshen, which was described in detail by five Native Americans kidnapped by George Waymouth in 1605 near St. Georges Harbor (11). Ferdinando Gorges (1565-1647) recorded their description, which Samuel Purchas published in Purchas’s Pilgrims (1623). James Rosier, who accompanied Waymouth and documented his voyage, describes the presence of 275 Abenaki warriors who approached Waymouth’s vessel, probably to trade, on the day prior to the kidnapping. These natives were residents of the Abenaki community in central coastal Maine historically known as the Wawenoc, who lived between the Penobscot and Kennebec Rivers and used rapid canoe travel to trade in oysters, furs, and corn throughout the Confederacy. Later trade with the French involved exchange of furs and moose hides for axes, knives, kettles, and firearms. The oyster shell middens at Damariscotta (9) were among the largest in the world (see photo) and document the presence of a highly populated Abenaki community on the central Maine coast. Contemporary Map of the Wawenoc Homelands also known as the Norumbega Bioregion Oyster Shell Middens at Damariscotta Most of the oyster shells shown in this picture were excavated and used as fertilizer by local farmers in the 19th century Rufus King Sewall. 1895. Ancient voyages to the western continent: Three phases of history on the coast of Maine. Lincoln County News. pg. 24. The downfall of the Confederacy began at the Battle of Saco (12) in 1607, where the Souriquois (Tarrentines), which included the Micmac, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy, attacked and defeated the Abenaki of Mawooshen with the help of firearms supplied by the French. The ongoing fur trade wars between competing Native American communities culminated in the Battle of Hatchet Mountain in Hope (13) (1615), where the last Bashebas or chieftain of Mawooshen, possibly Asticou, was killed. “[Bessabez] had under him many great Subjects... some fifteen hundred Bow-Men, some others lesse, these they call Sagamores... [He] had many enemies, especially those to the East and North-East, whom they call Tarrentines... [H]is owne chief abode was not far from Pemaquid, but the Warre growing more and more violent between the Bashaba and the Tarrentines, who (as it seemed) presumed upon the hopes they had to be favored of the French who were seated in Canada[.] [T]heir next neighbors, the Tarrentines surprised the Bashaba and slew him and all his People near about him.” (Gorges 1890). In 1617-18, a vast pandemic, probably viral hepatitis, swept the New England coast, killing 90% of the First Nation population east of the Narragansetts in Rhode Island, including all but one member of the Plymouth community of Pawtuxet. Only a few hundred Wawenocs, including Samoset, who lived on Muscongus Island (14), survived to witness English settlers arriving at Pemaquid (7) in 1623 at what was then New England’s busiest port. Use of Native Americans to help with careening and contaminated trade goods were the two most important sources of pathogens that caused the great virgin soil epidemic that swept the New England coast in 1617. Illustration from Jane Curtis, Will Curtis and Frank Lieberman. (1995). Monhegan the Artists’ Island. Down East Books, Camden, ME, pg. 14. The lingering presence of the Wawenoc community was noted in hundreds of documents, letters, and town/state histories. Frank Speck interviewed Francis Neptune, the last speaker of the Wawenoc dialect, at Bécancour, Quebec in 1912. Academic revisionists deleted mention of this First Nation community after 1990, as well as other Abenaki riverine communities, such as the Kennebecs; they are now referred to as “western Etchemins” (Prins and McBride 2007). Bourque’s Twelve Thousand Years: Native Americans in Maine (2001) makes no mention of either the Wawenoc nation (15) or the Confederacy of Mawooshen. Wawenock Homelands. Drawn by Kerry Hardy, Merryspring Nature Center, Camden The Wawenoc Homelands are still clearly still represented on the map of Penobscot territories (1928). A detailed explanation of the ecology of the rich natural resources of the Wawenoc and other First Nation community homelands can be found in Hardy’s Notes on a Lost Flute (2009). Penobscot Tribe Map. From Speck (1928) and Norumbega Reconsidered, pg. A-26, fig. 24. Bibliography: Suggested Reading Baker, Emerson W., Churchill, Edwin A., D’Abate, Richard S., Jones, Kristine L., Konrad, Victor A. and Prins, Harald E. L., Eds. (1994). American beginnings: Exploration, culture, and cartography in the land of Norumbega. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE. Bourque, Bruce J. (2001). Twelve thousand years: American Indians in Maine. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE. Brack, H. G. (2010). Norumbega reconsidered: Mawooshen and the Wawenoc diaspora. Pennywheel Press, Hulls Cove, ME. Gorges, Ferdinando. (1890). Sir Ferdinando Gorges and his Province of Maine. In: Publications of the Prince Society. Baxter, James P. Ed., Vol. 2. No. 19. Burt Franklin, NY. Greene, Francis B. (1906). History of Boothbay, Southport, and Boothbay Harbor, Maine 1623 - 1905 with family genealogies. Loring, Short and Harmon, Portland, ME. Hadlock, Wendell S. (1941). Three shell heaps on Frenchman’s Bay. Bulletin VI, The Robert Abbe Museum, Bar Harbor, ME. Hale, Richard W. (1949). The story of Bar Harbor, an informal history recording one hundred and fifty years in the life of a community. Ives Washburn, NY. Hardy, Kerry. (2009). Notes on a lost flute: A field guide to the Wabanaki. Down East Books, Camden, ME. Mitchell, Harbour, III and Spiess, Arthur E. (Spring 2002). Early archaic bifurcate base point occupation in the St. George River valley. Maine Archaeological Society Bulletin. 42(1). pg. 15-24. Morey, David C. (2005). The voyage of Archangell: James Rosier’s account of the Waymouth voyage of 1605 - A true relation. Tilbury House, Gardiner, ME. Mosher, John and Spiess, Arthur. (2004). An archaic site at Mattamiscontis on the Penobscot River. The Maine Archaeological Society Bulletin. 44(2). pg. 1-35. Prins, Harald E. L. and McBride, Bunny. (2007). Asticou’s island domain: Wabanaki peoples at Mount Desert Island 1500-2000. Vols. 1 and 2. Acadia National Park and The Abbe Museum, Bar Harbor, ME. Purchas, S. (1625). The Description of the country of Mawooshen, discovered by the English in the Yeere 1602.3.5.6.7.8. and 9. In: Hakluytus posthumus or Purchas his pilgrims. Vol. 4. Henry Fetherston, London. Rosier, James. (1605). A true relation of the voyage of Captaine George Weymouth. Reprinted in Burrage, Henry, S. Ed. (1930). Early English and French voyages chiefly from Hakluyt 1534-1608. Charles Scribner’s Sons, NY. Russell, Howard S. (1980). Indian New England before the Mayflower. University Press of New England, Hanover, NH. Sewall, Rufus King. (1859). Ancient dominions of Maine. Bath, ME. Sewall, Rufus King. (1895). Ancient voyages to the western continent: Three phases of history on the coast of Maine. Lincoln County News. pg. 24. Snow, Dean. (1980). The archaeology of New England. Academic Press, NY. Speck, Frank G. (1928). Wawenock myth texts from Maine. 43rd Annual Report of the Bureau of American ethnology. Bureau of American Ethnology, Washington, DC. Spiess, Arthur E. and Cranmer, Leon. (Fall 2001). Native American occupations at Pemaquid: Review and results. Maine Archaeological Society Bulletin. 41(2). pg. 1-25.