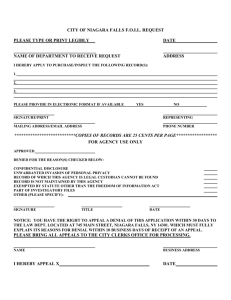

supreme court of canada

advertisement

CLERKSHIP

HANDBOOK

Hiring for 2012/13

Career & Professional Development Office

Faculty of Law

The University of Western Ontario

London, ON

Career Services Office

Faculty of Law

University of Calgary

Calgary, AB

Career Development Office

Osgoode Hall Law School

York University

Toronto, ON

Career Development Office

Faculty of Law

McGill University

Montreal, QC

Career Services Office

Faculty of Law

University of New Brunswick

Fredericton, NB

October 2010

1

FOREWORD

The first eight editions of the Clerkship Handbook were updated and published by the Faculty of

Law at the University of Western Ontario. This ninth edition is the result of a collaborative effort

between various faculties of law across Canada.

In this handbook, you will find helpful information about selected clerkship programs offered

throughout Canada. It represents a compilation of data contained in brochures produced by the

courts as well as research, advice and comments from judges, past and present clerks, law

professors, students and career offices. This latest edition also includes information from a

wider range of Canadian courts.

While this Handbook endeavours to be as up–to–date and accurate as possible, it is

advised that you refer to specific postings and websites to cross–reference information.

It should also be noted that, at the time of publication, the courts in Manitoba, Newfoundland

and Prince Edward Island did not have formal clerkship programs.

2

Table of Contents

CLERKING ............................................................................................................................................... 4

APPLICATION DEADLINES FOR 2012–2013 CLERKSHIPS ............................................... 5

APPLICATION INFORMATION ........................................................................................................ 7

SUPREME COURT OF CANADA .................................................................................................. 10

FEDERAL COURT & FEDERAL COURT OF APPEAL ......................................................... 15

TAX COURT OF CANADA ............................................................................................................... 19

COURT OF APPEAL FOR ONTARIO .......................................................................................... 23

ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE & ........................................................................ 28

ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE–DIVISIONAL CRT....................................... 28

COUR D’APPEL DU QUÉBEC ....................................................................................................... 32

BRITISH COLUMBIA COURT OF APPEAL & .......................................................................... 35

BRITISH COLUMBIA SUPREME COURT .................................................................................. 35

COURT OF APPEAL OF ALBERTA ............................................................................................. 39

COURT OF QUEEN’S BENCH OF ALBERTA .......................................................................... 43

PROVINCIAL COURT OF ALBERTA ........................................................................................... 46

COURT OF APPEAL FOR SASKATCHEWAN ......................................................................... 48

COURT OF QUEEN’S BENCH FOR SASKATCHEWAN ...................................................... 52

SASKATCHEWAN PROVINCIAL COURT ................................................................................. 55

NOVA SCOTIA COURT OF APPEAL .......................................................................................... 58

NEW BRUNSWICK COURT OF APPEAL .................................................................................. 60

CLERKING IN IQALUIT, NUNAVUT - NUNAVUT COURT OF JUSTICE ........................ 62

APPENDIX ............................................................................................................................................. 66

WHY YOU SHOULD APPLY FOR A CLERKSHIP AT THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA

............................................................................................................................................................................... 66

CLERKING AT THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA .................................................................... 68

CLERKING AT THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA .................................................................... 82

CLERKSHIP AT THE FEDERAL COURT OF APPEAL FOR MR. JUSTICE SEXTON .......... 84

CLERKING AT THE COURT OF APPEAL FOR ONTARIO............................................................. 87

CLERKING AT THE COURT OF QUEEN’S BENCH AND COURT OF APPEAL OF

ALBERTA .......................................................................................................................................................... 91

CLERKING AT THE COURT OF QUEEN’S BENCH AND COURT OF APPEAL OF

ALBERTA .......................................................................................................................................................... 94

ADVICE AND COMMENTS FROM OSGOODE ALUMNI ................................................................. 96

CLERKSHIP INTERVIEW EXPERIENCES ............................................................................................ 99

3

CLERKING

A.

INTRODUCTION

Clerking is a prestigious and unique alternative to articling. Judicial clerkships are usually 12–

month terms that satisfy the “articling” requirement of the licensing process. However, clerking

is not restricted to your articling year. Some law school graduates clerk after graduate school or

following their call to the bar. Several courts in Canada, both at the trial and appeal levels, offer

clerking opportunities. Under the direction of one or more justices, clerks research points of

law, prepare memoranda of law, and attend court proceedings. In short, they learn how the

justice system works.

B.

ADVANTAGES OF CLERKING

Challenging opportunities to learn about diverse areas of law and advocacy skills;

Receiving unique insights into how complex legal and policy arguments are decided;

Gaining a solid understanding of court procedures, rules of civil procedure, sentencing

principles, rules of statutory interpretation, and (where applicable) standards of appellate review;

Developing strong legal reasoning and legal writing skills;

Having personal contact with judges and the opportunity to candidly discuss cases with judges;

Benefiting from high prestige of position in future academic and career endeavors, including

graduate school, work with law firms, the government, and internationally. For example, some

U.S. firms regard clerkships highly and may “credit” clerks (i.e. hiring them as second year

associates after clerkship) and offer other significant bonuses to clerks;

Manageable work hours (40–50 hrs./wk.) depending on the judge, clerk, and circumstances.

C.

DRAWBACKS OF CLERKING

No “hirebacks” at courts – however, employment prospects for former clerks are usually quite

favourable and at some courts clerks join a hiring pool for government positions;

Clerk salaries are significantly lower than those at large firms;

Fees associated with the lawyer licensing process are not usually covered.

4

APPLICATION DEADLINES FOR 2012–2013 CLERKSHIPS

OCTOBER

October 31, 2010

Court of Appeal for Saskatchewan

NOVEMBER

Early November

Nunavut Court of Justice

{For 2011 – 2012}

DECEMBER

December 1, 2010

(by Noon)

Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta

{Both Edmonton and Calgary}

December 1, 2010

(by Noon)

Court of Appeal of Alberta

{Both Edmonton and Calgary}

December 31, 2010

Tax Court of Canada

JANUARY

January 4, 2011

(by 3:00 p.m.)

Supreme Court of Canada – submit to the SAO

End of January

New Brunswick Court of Appeal

January 24, 2011

(by 4:30 p.m.)

British Columbia

(Supreme Court and Court of Appeal)

January 28, 2011

Federal Court & Federal Court of Appeal

January 28, 2011

Court of Appeal for Ontario

January 28, 2011

(by 5:00 p.m.)

Ontario Superior Court of Justice

January 28, 2011

(by 5:00 p.m.)

Ontario Superior Court of Justice –

Divisional Court

FEBRUARY

Early February

Cour d’appel du Québec

5

February 18, 2011

Court of Queen’s Bench for Saskatchewan

MARCH

March 31, 2011

Provincial Court of Alberta

{Both Edmonton and Calgary}

March 31, 2011

Nova Scotia Court of Appeal

MAY

May 13, 2011

Saskatchewan Provincial Court

** These courts have specifically requested the Faculty of Law to collect applications from

students before the official deadline; therefore, students should treat Faculty’s internal deadline

date as final.

6

APPLICATION INFORMATION

A.

GENERAL

Students should consult the section on the courts for specific application requirements. Keep

the following points in mind:

Generally, application deadline dates are much earlier than private firms with most

falling in January and February but others even earlier.

Application requirements also differ as a sample of legal writing, official transcripts

(not copies), reference letters, and a recommendation from the Dean may be required.

Depending on the level of court, clerkships can be highly competitive. Students with

strong academic interests and standing have the best chance of clerking at the most

senior levels of courts, especially at the Supreme Court of Canada. However, do not

make the erroneous assumption that your grades and other qualifications will prevent

you from securing a valuable clerkship. Generally, the courts are looking for students

who have a record of solid academic performance, not straight A’s.

Start early! This includes researching the various courts, drafting your application, and

obtaining reference letters.

If you have general questions about clerkships, students can contact Catherine Bleau, Director

of the Career Development Office – catherine.bleau@mcgill.ca. For questions about Supreme

Court clerkships, please contact Professor Hoi Kong – hoi.kong@mcgill.ca.

B.

COVER LETTER, RÉSUMÉ, AND REFERENCES

Draft your cover letter and résumé specifically for the clerkship application process, focusing on

your research and writing skills.

Unlike résumés that are submitted to traditional law firms, courts tend to look for more

substantive material; therefore, your résumé can be longer than two pages.

Keep in mind most courts are looking for:

strong analytical ability to deal with complex legal arguments, critically and logically;

excellent writing skills, with the ability to clearly summarize long and complex arguments;

excellent research abilities, and in general, good problem–solving abilities; and,

strong capacity to work collegially, as well as to take initiative and to work independently

Your best references will come from law professors who know you and can comment on your

research and writing skills. Therefore, doing independent research projects with a professor is a

great way to build an academic relationship.

7

Acquiring reference letters from professors who have clerked with the particular court you are

applying to is helpful. References from former non–academic employers and law firms are not

as relevant.

Remember to give your referees plenty of time to draft the letters and also be sure to supply

them with a copy of your most current résumé as well as the correct address and contact

name for the court to which you are applying. To avoid confusion, also remind your referees

to indicate your name on the front of the sealed reference letter, particularly if it is being sent

independent of your application.

C.

WRITING SAMPLE

Many courts require one or more writing samples and/or generally look for strong research and

writing skills. Here are a few suggestions:

D.

It is a good idea to have a legal paper, case comment, or article that you can include

with your application or make reference to in your cover letter and/or interview. If a

court does not require a writing sample, it is still recommended that you make reference

to one in your cover letter.

If submitted with your application, the writing sample need not be the copy graded by the

professor. In fact you can make any changes or corrections recommended by the

professor to improve your paper.

If a court asks candidates to submit “writing samples” but does not specify how many,

assume that two samples are sufficient. If you have more than 2 samples that you

would like to include, feel free to do so.

TRANSCRIPTS

A number of courts require official transcripts, not copies, to be included with the application.

Official transcripts are sent by the institution directly to a third party or are given to the student in

a sealed envelope. Turnaround time can be lengthy so remember to order them early. Be

sure to include all post–secondary transcripts, including CECEP marks (for Quebec students).

Additional notes:

If you are applying to the Supreme Court of Canada, remember to include your sealed transcript

with the application you submit to the Student Affairs Office (SAO, NCDH 433).

If your Fall Term marks are not available by the deadline, you should include the most recent

transcript with your application. When your up–to–date transcript that includes your Fall Term

marks becomes available, send it to the court. If you are making such arrangements, indicate

this in your cover letter.

E.

TIPS FROM STUDENTS WHO ARE FORMER LAW CLERKS

8

Clerks must possess research, writing, and summarizing skills. Thus, gain experience and

polish your skills while in law school.

Clerks must be confident in their abilities and must be able to give their opinions to judges.

It is recommended that you clerk as soon after law school or graduate schools as possible

because your chances for being hired as a clerk are better then.

Do not be discouraged from applying even if you feel your grades are not competitive

enough. Varying past experiences and connections formed with judges during interviews

may get you the job!

Apply to as many courts as possible even if you think you are not competitive enough for a

certain court.

Consider clerking for more than one court. The experience will give you comparative and

in–depth insights into the Canadian judicial system.

Students should enjoy legal research and must have the ability to process information very

quickly.

Do some research and writing early on apart from the 1st year legal research and memo

writing assignment. Take on an independent study project or work on getting a publishable

article out of a seminar with a paper requirement.

At the Supreme Court of Canada, judges are looking for good academic researchers, not

litigators. They are also looking for people who want the experience for its own sake, and

not as a stepping stone to something else.

9

SUPREME COURT OF CANADA

A.

INTRODUCTION

There are approximately 27 clerkships available with the Supreme Court of Canada in Ottawa,

Ontario, running from the beginning of August or September to the end of July or August of the

following year. In the past, some clerks began in January and ended their term in December.

Each Justice hires 3 clerks, often including 1 clerk who holds a civil law degree. By agreement

with the individual Justice, the period of employment may be extended for a period not

exceeding an additional 12 months. The Law Society of Upper Canada recognizes these

clerkships as fulfilling the articling requirement. It should be noted, however, that not all law

societies recognize service as a law clerk as fulfilling all or part of their articling requirements.

Completed applications must be received by the Student Affairs Office (SAO) by the

deadline. A summary of the application process is on p. 14. If you have any questions

about the application process, please consult Professor Hoi Kong (514-398-2945).

The Supreme Court asks all law school Deans to review applications and prepare a cover letter

for use by the Court. Following the deadline date and before the cover letter is prepared, the

Dean may wish to meet with the applicants individually. If so, you will be notified by his office.

B.

SALARY AND BENEFITS

At present the annual salary is $59,009 plus a fixed amount to assist with relocation from any

point in Canada to Ottawa and return. Law clerks will be engaged as term employees within the

Public Service and as such will receive benefits and conditions of employment as term

employees.

C.

DUTIES

A law clerk, under the direction of the Judge for whom the clerk works, researches points of law,

prepares memoranda of fact and law and generally assists the Judge in the work of the Court.

Furthermore, law clerks are expected to devote their full time and attention to the performance

of their duties. No time off is permitted to attend any bar admission course or examination

which may occur during the period of employment.

There is an article in the Appendix by Professor Erika Chamberlain on “Why You Should Apply

for a Clerkship at the Supreme Court of Canada”.

For more information about law clerks and the role they play at the Supreme Court see the

article on clerking coauthored by Mitchell McInnes, Janet Bolton and Natalie Derzko that

appears at the end of this booklet.

D.

QUALIFICATIONS

Bachelor of Laws or a Juris Doctor from a recognized Canadian university or its equivalent is

required. Proficiency in one official language is mandatory. Candidates are requested to

10

indicate their level of proficiency in both official languages in reading, written and oral

proficiency. Only persons holding Canadian citizenship or having permanent resident status in

Canada or a work permit for Canada may apply. You must indicate in your application the basis

on which you are entitled to work in Canada. Preference is given to Canadian citizens.

Applications made by persons who are not Canadian citizens are accepted, however, if there

are sufficient qualified applicants who are Canadian citizens, the selection will be confined to

those applicants.

E.

THE APPLICATION

Completed applications must be received by the SAO by Tuesday, January 4, 2011. Following

McGill’s internal process, applications will be forwarded to the Supreme Court before the

January 24, 2011 deadline.

Applications should include the following:

1. A cover letter which addresses all requirements as listed on the posting;

2. A curriculum vitae;

3. official transcripts of all marks obtained in post–secondary studies, including law school and

any other post-graduate courses; **No Photocopies**

4. Four sealed letters of reference [which will include one from the Dean] addressed to: Cara

McLean, Chambers of the Chief Justice of Canada. One of these references may be from

the present Dean of the faculty where the applicant obtained his or her law degree. The

letters may be included with your application or sent separately by the persons who have

agreed to forward references.

The Supreme Court requirements specify that you need references from “four (4) persons,

including the Dean of Law.” You need only include three sealed letters of reference as the

Dean’s letter will be prepared after you have submitted all the above material. The Supreme

Court has not requested a writing sample so do not include one as it will not be considered.

However, it is recommended that you make reference to your writing in your cover letter. Note

that incomplete or late applications will not be circulated or considered.

Again, students must clearly indicate in their cover letters how they meet the requirements of

the position. The letter must not exceed one page.

All materials/envelopes should be clearly marked “Clerkship Application 2012−2013”.

All letters should be addressed to:

Ms. Cara McLean

Chambers of the Chief Justice of Canada

Supreme Court of Canada

301 Wellington Street

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0J1

Questions may be directed to:

Ms. Cara McLean

Chambers of the Chief Justice of Canada

11

lcp-paj@scc-csc.gc.ca

F.

INTERVIEWS

Only those selected for an interview will be contacted and at that time will be asked to provide

two (2) writing samples. The Judges of the Court will conduct interviews during the week of

March 7, 2011. Candidates to be interviewed will be advised by letter, e-mail or telephone and

should include in their materials an address, e-mail address and telephone number where they

can be reached or a message can be left during the day. All hiring will be completed by April 1,

2011. Unsuccessful interviewees will be advised by April 1, 2011, or as soon as possible

thereafter.

G.

APPLICATION AND INTERVIEW ADVICE FROM UWO STUDENTS, CLERKS,

PROFESSORS AND VISITING JUDGES

Applications and Interviews

Do not be discouraged if you do not get a position after 2nd year. The clerkship application

process is extremely competitive and it is not uncommon to see SCC clerks who have

recently been called to the bar or who are lawyers who have been in practice for a few

years. Because the SCC is very competitive and marks are the easiest way to narrow the

applicant pool, strong academics are very important. Your best references will come from

professors who can comment on your research and writing skills. If possible, have

something you can show the judge, such as a legal paper, case comment, or article. –

Wendy Adams, Professor and Former SCC Clerk (Oct/99)

The SCC is looking for someone with good marks (strong B+ average), experience, and

reference letters. The reference letters should be academic. This does not necessarily

mean you have to get letters from law professors only. For example, well–known political

science professors or constitutional scholars are very good references. References from

former non–academic employers and law firms are less relevant. Keep in mind that

interviewers want you to do well. You should be prepared − know your CV, re–read any

relevant articles, legal papers, or cases. – Richard Gold, Professor and Former SCC Clerk

(Oct/98)

Draft your cover letter and résumé specifically for the clerkship application process,

focussing on research and writing skills as well as your community interests. I had

interviews with the SCC and with law firms. The SCC seems interested in you as a full

individual (e.g. what does law mean to you, what issues are you interested in, etc). I found it

very helpful to consult with professors when I was preparing my application. References

make ALL the difference so make sure you have established relationships with professors.

Also make sure you do not see your reference letters – they have more value that way. The

SCC is not generally looking for one–dimensional people. Good marks and good writing

skills are not necessarily enough. The Court looks for community mindedness as well.

Therefore, you should keep up your extra–curriculars while you are in law school. UWO

Grad and 1999/00 SCC Clerk (Oct/98)

12

The interviews are generally 30 minutes each and are conducted by the judges individually.

They are scheduled consecutively; therefore, if you have more than one, be prepared to

interview without a break. Each judge has a very different interview style. Some will ask

substantive questions while others do not. Some will engage you in a debate about judicial

activism. It’s not a bad idea to have a case in mind that you are interested in and

knowledgeable about and offer it up for discussion. Former UWO Student and 2000/01

SCC Clerk (Oct/99)

13

SUPREME COURT CLERKSHIPS – POSTES D’AUXILIAIRES JURIDIQUES À LA COUR SUPRÊME

(for/pour 2012–13)

Applications for 2012–13 must be handed in at the SAO by

Tuesday 4 January 2011 (3:00 p.m.); an application

includes the following documents:

(1)

Les candidatures pour 2012–13 doivent être remises au plus

tard mardi le 4 janvier 2011 (15 h) au Secrétariat des études;

les candidats doivent fournir :

A curriculum vitae;

(1)

Un curriculum vitae;

(2)

Official transcripts of all marks obtained in all postsecondary studies (this includes CEGEP). If an institution

will not release an official transcript to you, have it sent

directly to Prof. KONG, c/o SAO (S.C.C. clerkship

applications), Faculty of Law, 3644 Peel, Montreal, H3A

1W9. For your legal studies at McGill, you may provide an

unofficial transcript, substituting an official transcript after

the January marks meeting.

(2)

Des relevés officiels de notes obtenues au cours de

toutes leurs études post-secondaires (ce qui comprend le

CEGEP). Si une institution ne remet pas de relevés officiels

aux étudiants, faites envoyer le relevé au Prof. KONG, a/s

Secrétariat des études (Stages à la C.S.C.), Faculté de droit,

3644 Peel, Montréal, H3A 1W9. Pour vos études juridiques à

McGill, vous pourriez fournir un relevé non officiel, y

substituant un relevé officiel après la publication des notes en

janvier.

(3)

A list of the names of three (3) referees who will

provide reference letters. The list should also mention that

your fourth referee is the dean.

(3)

Une liste des noms de trois (3) répondants qui

fourniront des lettres de recommandation. La liste doit aussi

mentionner que la quatrième lettre sera fournie par le doyen.

(4)

The three reference letters. These letters should be

addressed to: Office of the Chief Justice of Canada, Supreme

Court of Canada, Wellington Street, Ottawa, K1A 0J1, but

should be handed in to SAO by 4 January 2011 (3:00 p.m.).

(4)

Les trois lettres de recommandation. Ces lettres

doivent être adressées à : Cabinet du Juge en chef du Canada,

Cour suprême du Canada, rue Wellington, Ottawa, K1A 0J1,

mais doivent être remises au Secrétariat des études au plus tard

le 4 janvier 2011 (15 h).

(5)

A cover letter explaining why the position of law

clerk is being sought and addressing all requirements stated

on the posting found at http://www.scc-csc.gc.ca/empl/lcaj/prog-eng.asp. This letter must not exceed one page.

Address it to the Office of the Chief Justice of Canada; Dear

Chief Justice and Justices of the Supreme Court.

(5)

Une lettre motivant votre demande pour un poste

d’auxiliaire juridique et indiquant que vous satisfaites à toutes

les exigences mentionnées dans l’avis disponible à

http://www.scc-csc.gc.ca/empl/lc-aj/prog-fra.asp.

Vous

devriez vous en tenir à une seule page et adresser la lettre au

Cabinet du Juge en chef du Canada.

Students are responsible for ensuring that their application is

COMPLETE and at the SAO on 4 January 2011 (3:00

p.m.), to enable the dean to prepare a comparative letter of

reference as required by the Supreme Court. Incomplete or

late applications will not be considered.

Les candidats doivent s'assurer que leur demande est complète

et que TOUS les documents, y compris les lettres de

recommandation, sont au Secrétariat des études en date du

4 janvier 2011 (15 h), afin de permettre au doyen de préparer

une lettre de recommandation comparative tel que requis par la

Cour suprême. Les demandes incomplètes ou tardives ne

seront pas considérées.

The dean’s office forwards all of the applications directly to

the Supreme Court late in January 2011 by courier.

Le bureau du doyen s’occupe d’envoyer toutes les demandes à

la Cour suprême à la fin de janvier 2011 par messager.

For further information:

Pour plus d’information :

Prof. Hoi Kong

Supreme Court Clerkship Coordinator

398-2945; hoi.kong@mcgill.ca

Prof. Hoi Kong

Coordonnateur des stages à la Cour suprême

398-2945; hoi.kong@mcgill.ca

14

FEDERAL COURT & FEDERAL COURT OF APPEAL

A.

INTRODUCTION

The Federal Court [Trial Division] and the Federal Court of Appeal are national and bilingual

Courts. Judges of the Courts travel extensively as they sit in every province. There are normally

44 clerkships available: 12 clerks are hired for the Federal Court of Appeal and 32 for the

Federal Court. Each judge of the Court, except for those who have elected supernumerary

status, has a law clerk.

The Law Society of Upper Canada recognizes these one–year contract positions as fulfilling the

articling requirement. Other provinces may give partial credit to clerking to satisfy articling

requirements. Candidates should verify this with the law society of the jurisdiction in which they

will seek admission to practice.

Law clerks for the Federal Court and the Federal Court of Appeal will begin their terms on

Tuesday, August 7, 2012.

The Appeal Division serves as the following:

Appellate body of the Trial Division of the Federal Court of Canada;

Appellate body of the Tax Court of Canada; and

Court of original jurisdiction for judicial review applications of federal boards such as the

Canadian

Labour

Relations

Board,

the

Canadian

Radio−Television

and

Telecommunications Commission, and the Human Rights Commission of Canada.

The Trial Division deals with matters (other than tax) that fall under federal jurisdiction. This

includes the following areas of law:

intellectual property law (patent, copyright, and trademark);

admiralty law;

refugee and immigration law;

aboriginal law;

human rights law;

constitutional law;

Crown liability (concurrent jurisdiction with Superior Court of Justice); and

reviews of federal minister decisions.

Completed applications must be sent directly to the Court and received by their deadline.

B.

SALARY AND BENEFITS

Salary - $55, 102 per annum.

Vacation – 3 weeks (15 working days)

Sick leave entitlement – sick leave entitlement is credited at the rate of 1.25 days per

month.

Volunteer leave – 1 day per fiscal year.

15

C.

Personal leave – 1 day per fiscal year.

Benefits –

o Dental Plan (premiums presently covered by employer);

o Public Service Health Care Plan (optional – employee and employer contribute);

o Long Term Disability Insurance (mandatory);

o Death Benefits (mandatory); and

o Superannuation Plan (mandatory).

Relocation allowance – taxable lump sum allowance based on the distance of relocation

and the number of dependants. The allowance is also payable at the end of the clerkship

term under certain conditions.

DUTIES

Under the direction of the Judges to whom they have assigned, law clerks research points of

law, prepare legal memoranda, edit judgments and assist in the preparation of speeches and

papers for presentation by a judge. At the Federal Court, law clerks also assist the

Prothonotaries. The areas of law to which the law clerks are exposed include administrative

law, Crown liability, intellectual property, admiralty, immigration, income tax, human rights,

aboriginal and environment law.

D.

CAREER PROSPECTS

The Federal Court of Canada literature refers to the success its law clerk programme

participants have had in securing employment after their call to the bar. While the majority are

now counsel at major law firms in Canada and abroad or with the Federal Department of Justice

or other agencies, others are counsel with various organizations such as the Canadian Medical

Association, Stentor Telecom Policy Inc., Mutual Life Assurance Co. and Superior Propane Inc..

Some have become law professors while others have become provincial Crown Attorneys.

Finally, some are with the United Nations and Foreign Affairs.

Following completion of the one−year clerkship term, law clerks are permitted to take 12 months

leave without pay. During this period, the law clerks remain eligible to apply for legal advisory

and other positions open only to employees of the Federal Public Service.

E.

QUALIFICATIONS

1. Bachelor of Laws or Juris Doctor or other law degree from a recognized Canadian Law

school or equivalent;

2. Language requirements vary according to the position. Proficiency in one of the official

languages is mandatory. Proficiency in the other official language is required for certain

positions only.

Please note that preference will be given to Canadian citizens. The Federal Court of Canada is

committed to employment equity.

F.

THE APPLICATION

16

Candidates must provide the following materials by January 28, 2011:

NOTE: Envelope must be clearly marked with “Law Clerkship Application 2012−2013”

1. a curriculum vitae [specify citizenship];

2. official transcripts of law school marks and copies of transcripts for all other post–secondary

studies;

3. three (3) letters of reference;

4. a letter explaining why the position is being sought (i.e. cover letter); and

5. one (1) sample of legal writing which the candidates have written themselves.

An application will be considered provided the documents over which the student has control

(curriculum vitae, letter of explanation and writing samples) are filed by the deadline. Official

transcripts and letters of reference which will be sent directly to the Court may follow; however,

the student should indicate in the cover letter that arrangements have been made for them to be

sent to the Court.

All material should be sent to:

Mr. Marc D. Reinhardt, B. Admin. – LL.L.

Director, Law Clerkship Program

Courts Administration Service

90 Sparks Street, 5th floor mailroom

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0H9

If you are applying to both the Appeal and Trial Divisions, you only need to submit one

application, as applications will automatically be considered for both Courts unless

indicated otherwise. If you are applying to only one, indicate this in your covering letter. For

further information regarding Federal Court of Appeal clerkships, please contact Mr. François

Giroux at (613) 995-4549 or by email at francois.giroux@cas-satj.gc.ca. For further information

regarding Federal Court clerkships, please contact Mr. Marc D. Reinhardt at (613) 995−4547 or

by e-mail at marc.reinhardt@cas-satj.gc.ca.

You may also visit the following websites:

Federal Court of Appeal www.fca-caf.gc.ca

Federal Court www.fct-cf.gc.ca

Courts Administration Service at www.cas-satj.gc.ca

G.

INTERVIEWS

Interviews will take place between February and May 2011 and are conducted by judges of the

Federal Court of Appeal and the Federal Court, either at the law school or at the Court’s local

office closest to the law school. Second and subsequent interviews may be held.

The selection process is usually completed by the middle of June in conjunction with most of the

Ottawa firms that hire articling students. However, where there are new judicial appointments to

the Court, interviews may be held at any time. Additional clerks may be hired right up to the

time the clerkship term begins. Students should note that these additional positions are not

17

always advertised; therefore, interested candidates should ensure they inform the Court of their

continued interest.

H.

APPLICATION AND INTERVIEW ADVICE FROM UWO STUDENTS, CLERKS,

PROFESSORS, AND VISITING JUDGES

The interview tends to be informal. The judges want to discover what kind of person you

are, your interests, and your ability to interact with others. – Lemieux J. (Oct/99)

18

TAX COURT OF CANADA

A.

INTRODUCTION

There are approximately 12 clerkships available with the Tax Court of Canada in Ottawa. This

number changes depending on operational requirements. Unlike other courts, students are not

assigned to any particular judge. However, discussion and interaction with the judges is

encouraged, and generally the judges have an open door policy.

The provincial law societies generally recognize articling at the Tax Court of Canada as fulfilling

all or part of their articling requirements. The Law Society of Upper Canada recognizes it in full.

However, it is the responsibility of the applicants to confirm this with the law society in question.

Currently, there are approximately 25 judges at the Tax Court of Canada. The Tax Court of

Canada deals with disputes between individuals and the Crown arising under the Tax Court of

Canada Act or any other act under which the Court has original jurisdiction.

As described in its literature, the Tax Court of Canada offers Canadians the following:

an independent review of Canada Customs and Revenue Agency (CCRA)

decisions;

an independent review of applications for extensions of the time for appealing to

the TCC or the Federal Court of Canada;

at the CCRA’s request, the interpretation of legislation within the TCC’s fields of

jurisdiction;

the awarding to parties of legal costs arising out of court proceedings; and

the provision of information and documents on appeals before the Court and on

its past decisions.

Although the focus of the Court is on tax law, cases that come before the Court may involve

other areas of law such as corporate and commercial, family, constitutional, contracts, trusts

and estates law, among others.

Law clerks are generally hired on a determinate basis for a period of 12 consecutive months.

Starting date will be August 2, 2011, subject to operational requirements.

Completed applications must be sent directly to the Court and received by their deadline.

B.

SALARY AND BENEFITS

The current salary is $54,288. Clerks also receive 3 weeks (15 working days) of paid vacation.

Sick leave entitlement is credited at the rate of 1.25 days per month. Benefits include: dental

care plan, public service health care plan, disability insurance, death benefits, superannuation

plan.

C.

DUTIES

19

The majority of the workload consists of:

preparing legal opinion of fact and law prior to the hearing of a case as well as

following the hearing of a case;

researching specific legal questions; and

reviewing, editing, and commenting on draft reasons for judgment.

The majority of files that the law clerks work on are appeals arising under the Income Tax Act

and Part IX of the Excise Tax Act (GST).

The clerks are usually not assigned to work for any one judge; rather, each judge decides

whether he or she requires the assistance of a clerk. The clerk co–coordinator ensures there is

an even workload among the clerks. When assigned to a file, a clerk usually works with a judge

on that file until it is closed, which may often take up to 9 months.

D.

CAREER PROSPECTS

Following their clerkship, many law clerks have great success moving into the tax practice of a

traditional law firm, the Department of Justice or the Department of Finance. Because of the

specialized knowledge they gain during their clerkship, law clerks often excel in tax litigation.

E.

QUALIFICATIONS

1. Graduation from a recognized Canadian law school or a law degree recognized by a

provincial law society;

2. Interest and proficiency in tax law and commercial transactions;

3. Introductory course in tax law and at least one additional course in tax law such as

international taxation or corporate tax prior to graduation;

4. Proficiency in both official languages is an asset but is not essential. Some positions will be

designated as bilingual;

5. Preference will be given to Canadian citizens;

6. Any appointment is subject to the applicant receiving a law degree before October 1, 2012.

F.

THE APPLICATION

Candidates must forward the following by December 31, 2010:

1. a cover letter

2. a résumé;

3. official transcripts of law marks and copies of all other marks obtained in post–secondary

studies; and

4. a list of three (3) persons, including: a) a senior professor of your law faculty; b) a professor

who has taught you at least one course in tax law, and c) one other person. These

individuals will be forwarding references on your behalf.

It is recognized that transcripts and letters of reference that must be sent directly to the Court

may follow. However, the applicant should indicate in the covering letter that these

arrangements have been made, and the documents must arrive shortly after the application

deadline.

20

Provide your current address and telephone number and the addresses and telephone numbers

where you may be contacted. Please specify your citizenship on your résumé. While official

transcripts need not be submitted with applications, they may be requested at interviews.

Please note that the letters of reference and transcripts will not be returned.

Applications must be mailed to:

Tax Court of Canada

200 Kent Street

Ottawa, ON

K1A 0M1

Attention: Julie Lauzon, Executive Legal Counsel, Chambers of the Chief Justice.

Tel: (613) 995−4789 or 1−800−927−5499

Email: clerkships-TCC@cas-satj.gc.ca

The TCC adheres to the principle of employment equity.

A tour of the premises and communication with a current law clerk can be arranged at any time.

For further information, you may contact Julie Lauzon, Executive Legal Counsel, Chambers of

the Chief Justice, at (613) 995−4789 or 1−800−927−5499 or write to: clerkships-TCC@cassatj.gc.ca

G.

INTERVIEWS

A preliminary screening of applications will be done to determine which applicants will be invited

for a first interview.

The first interview normally takes place in the city where the applicant is attending law school

and is conducted by a judge of the Court who has a sitting nearby. In the event that applicants

are required to travel to attend an interview, travel expenses may be authorized in accordance

with Treasury Board guidelines. The first interview will take place during the months of

February and March 2011.

A second interview, for those who are invited, will take place in Ottawa during the month of May

2011. This interview will be with the judges on the Law Clerk Committee. The results are

usually communicated by telephone within the following weeks.

Candidates are required to provide the interview panel with a sample of their writing.

H.

APPLICATION AND INTERVIEW ADVICE FROM UWO STUDENTS, CLERKS,

PROFESSORS, AND VISITING JUDGES

The Court primarily hears cases pertaining to income tax, GST, and employment insurance.

It also hears Canadian Pension Plan, Export/Import, and extension of time cases. Sittings

are held throughout the country and the Court also has its own facilities in major cities

(including London). Where it doesn’t, it uses federal/provincial facilities. Although students

can attend sittings outside Ottawa, they must do so at their own [financial] cost. – Rip J.

(Oct/99)

21

Qualities the Tax Court looks for include the following: ability to get along with people, good

academics, prepared to work, interested in tax, and solid grounding in law. A background in

accounting can be helpful but the Court’s focus is on open–mindedness and a varied

background (e.g. in undergrad). These qualities are sought because the Court hears a

variety of cases. Often, an income tax case will involve real estate or trusts law issues.

Some judges in fact do not prefer candidates with an accounting background because of

their tendency to approach tax law from a business perspective rather than a legal one.

Although a specialization in tax is not required, students in Western’s Tax Concentration

Program have a definite advantage. – Rip J. (Oct/99)

If you are in the Tax Concentration Program, indicate this in your cover letter or reference

letter. Also specify what the program entails (how many and what types of tax courses you

are required to take, etc.). The Court is interested in candidates who know tax case law –

Western offers a whole course devoted to this subject. – UWO Grad and 1999/00 Clerk

(April/99)

Interviews tend to be informal; often, you are asked to discuss a tax case of interest to you.

– Rip J. (Oct/99)

My interview was scheduled with 5 judges and the administrator of the clerking program. It

lasted 30 minutes. The administrator had some input but did not ask questions. The Court

was interviewing 20 people in 2 days; therefore, the schedule was tight. Each judge asked

some questions. Priority seemed to be placed on bilingualism, work experience, and the

fact that I was interested in tax. There were some substantive questions. I was asked if I

had read any interesting cases lately, and was also asked what I thought about a case

pertaining to a controversial provision in the Income Tax Act (the general anti avoidance

rule). I believe it was important to my success that I answered questions honestly from a

position that I believed was correct, even though one of the judges disagreed with me. I

would not recommend taking a very aggressive stance, but I believe it is important to state

an educated and well thought opinion. Don’t be afraid to tell your interviewers exactly what

you want; there is nothing wrong with politely and professionally communicating your

expectations and wants. – UWO Grad and 1999/00 Clerk (April/99)

22

COURT OF APPEAL FOR ONTARIO

A.

INTRODUCTION

There are up to 17 clerkships available and the Law Society of Upper Canada recognizes these

as fulfilling the articling requirement.

The Court of Appeal for Ontario is located in historic Osgoode Hall in downtown Toronto. The

Court is comprised of 24 judges who hear over 1500 civil and criminal appeals each year.

These appeals relate to a wide variety of issues including commercial, administrative, family,

criminal, and Charter law issues. The Court also hears various young offender proceedings in

addition to appeals argued by inmates in Toronto and Kingston. In 98% of cases, the Court of

Appeal is the last avenue of appeal for litigants in the province.

Clerks are given the option of starting their clerkships either at the beginning of August or just

after Labour Day. All clerks are required to stay to the end of June and encouraged to stay for

the duration of their 12-month contracts.

Completed applications must be sent directly to the Court and received by their deadline.

B.

SALARY AND BENEFITS

Comparable to other clerkship and government articling positions.

C.

DUTIES

Each law clerk is assigned two rotations. During those rotations each clerk works with one or

two judges. Close exposure to a variety of judges ensures a wide range of experiences and

enables clerks to benefit from the knowledge and perspectives of several members of the Court.

Law clerks’ tasks can vary from judge to judge and include the following:

preparing bench memos summarizing facts, issues and arguments for judges prior to the

hearing;

engaging in pre− and post−hearing legal research in diverse areas of law;

critically appraising complex legal arguments;

editing draft judgments;

attending hearings and having the chance to observe outstanding advocates; and

discussing cases with judges.

Law clerks’ work with their individual judges is supplemented by activities and responsibilities

shared among the clerks. These additional responsibilities include organizing a seminar series,

in which members of the judiciary, prominent lawyers and other members of the legal

community are invited to discuss various topics with all of the law clerks. All clerks are given the

opportunity to travel to Kingston to assist judges in the hearing of appeals brought by

unrepresented prison inmates.

23

D.

CAREER PROSPECTS

In the Court’s brochure, the clerkship experience is described as one that equips law clerks with

skills and insights that enable them to follow one of numerous career paths. Because the

judges of the Court come from a variety of legal backgrounds, they are also able to provide

valuable advice and support to clerks in their employment search. Former clerks are now

pursuing successful careers in diverse areas, such as the following:

E.

Criminal Defence

Crown Prosecution

Academia

Politics

Corporate and Securities Law in Canada and the US

Civil Litigation

International affairs

Foreign Service

QUALIFICATIONS

The Court seeks applicants who are personable, well-rounded and who have strong academic

credentials. In addition, solid research, writing and analytical skills are important, as is the

ability to work well with judges and other staff. Bilingualism is an asset but is not required for

most positions. Applicants must be in their final two years of law school.

F.

THE APPLICATION

All application material must be received by the court by Friday, January 28, 2011.

All prospective candidates are required to submit the following as part of their application:

1. a cover letter [addressed to Justice Laskin]

2. a current curriculum vitae;

3. official transcripts of all university marks (photocopies of official transcripts are

acceptable);

4. two letters of reference (at least one from a law professor); and

5. one legal writing sample (do not submit a moot factum).

Application deadlines for the 2012-2013 Clerkship Program:

All candidates attending law schools in Ontario:

To your law school’s career services office by the internal deadline set by that office.

All other candidates submit directly to:

The Honourable Justice John Laskin

c/o Lori Levine

Coordinator, Legal Support Services

24

Court of Appeal for Ontario

Osgoode Hall, Concourse Level

130 Queen Street West

Toronto, Ontario M5H 2N5

Applicants are also invited to contact current articling students at the Courts if they have any

questions. Names and contact information of current articling students may be obtained from

the Courts’ brochure, or the posters. For further information, applicants are invited to visit the

Court’s web site at http://www.ontariocourts.on.ca/.

Travel Expenses to interviews in Toronto will be reimbursed up to $100.00 for those travelling

from within Ontario and up to $200.00 for those travelling from outside of the province of

Ontario. Complete a travel expense claim form when attending the Court for interviews.

G.

INTERVIEWS

All clerkship interviews will be the week of February 21 & 28, 2011 with one or more judges of

the Court. The judges usually travel to the Ontario law schools to conduct interviews. Some

schools’ Career Development Offices co–ordinate the interview schedule and then notify

students who have been selected. The Court will notify those selected to be law clerks for the

2012−2013 articling year by mid−late April 2011, but not before the Supreme Court of Canada

has completed its selection of clerks, whichever is later.

H.

APPLICATION AND INTERVIEW ADVICE FROM UWO STUDENTS, CLERKS,

PROFESSORS, AND VISITING JUDGES

The Court’s Frequently Asked Questions page, provides some excellent information on

the application and interview portions of the process –

http://www.ontariocourts.on.ca/coa/en/lawclerkprogram/faq.htm

The Court of Appeal processes a lot more cases than the SCC (approx. ten times the

caseload of the SCC). It also acts very much as a “gatekeeper” versus the SCC which

makes policy for the country. By gatekeeper, I mean it functions to prevent the

floodgates from opening based on decisions of the SCC. The Court of Appeal is an

intermediate appellate court and the highest court in Ontario and, therefore, it does set

the policy for Ontario. The Court also tends to be more practical. A number of the

judges have backgrounds in business law as compared to those of the SCC who may

have more academic backgrounds. The Court of Appeal generally does not have

discretion to decide whether to hear cases as the SCC does. – Richard Gold, Professor

and Former Ont.C.A. Clerk (Feb/99)

Although it is not a 9−5 job, the work schedule is manageable. My typical workday was

from 8:30−6:30. − UWO Grad and 1999/00 Clerk (Oct/99)

Clerks will tend to learn a lot more about advocacy at the Ont.C.A. than at the SCC. At

the Ont.C.A., clerks will see more facta and hear more arguments, both good and bad.

– Richard Gold, Professor and Former Clerk of the Ont.C.A. and S.C.C. (Feb/99)

25

The clerks review appeals that the judges think will be “troublesome” and the judges

generally look to the clerks for criticism of judgments. As to the work atmosphere, it is

excellent – it is collegial and informal and doors are open for discussion on a regular

basis. This year, the judges also organized a mock appeal for all interested clerks to

give them advocacy experience and immediate feedback. − O’Connor J.A. (Oct/99)

Aside from the typical responsibilities, clerks also spend a limited amount of time

engaging in recruiting, organizing desk books, and giving tours of the Court. The offices

of the clerks are separated from the offices of the judges. Generally, clerks keep a suit

in the office but otherwise dress casually. − UWO Grad and 1998/99 Clerk (Nov/98)

The Court looks for excellent writing, analytical, and problem solving skills. Any

experience that demonstrates these skills is valued (e.g. research assistant) – UWO

Grad and 1998/99 Clerk

Interviews are very short – each is scheduled for about ½ hour. The interview lasts

about 20 minutes (maximum) and the interviewers use the last 10 minutes to review

without the candidate present. There will usually be two judges and one law clerk

conducting the interview. They will have your résumé, transcripts, and writing sample

with them. You should be very familiar with your writing sample and it is possible that

you may be questioned on it. The interviewers typically do not ask substantive

questions. This is the only interview before a decision is made. It is important to be

yourself. Judges expect integrity and honesty; therefore, reflect these qualities in your

answers. You should answer questions with certainty, conveying the impression that

you will be clerking (i.e. after clerking, I plan to do X, Y, and Z). The Court usually

selects one or more clerks from each of the Ontario law schools. If you have interviewed

with the SCC, the Ont.C.A. will extend the time of the offer until you find out whether or

not you have received a SCC clerkship offer. This was not done in the past. – Richard

Gold, Professor and Former Ont.C.A. Clerk (Feb/99)

Some typical questions include:

Why do you want to clerk? This is one of the key interview questions and telling

them it will look good on your résumé is not a good answer. You should convey your

enthusiasm about clerking and your passion for the law clearly.

What do you plan to do after clerking/articling? What are your goals? Have you

applied to any other courts? What will you do if you are offered a position by the

Supreme Court of Canada, Federal Court of Canada, etc.?

Why do you want to clerk at the Ontario Court of Appeal? You should have an

understanding of what the Court does when you answer this question – articulate this

or have it in mind when you give an answer. You should also read the literature

available on the work of the Court. − Richard Gold, Professor and Former Ont.C.A.

Clerk (Feb/99)

Comments on Career Prospects

Hiring record is excellent. At Borden & Elliot (where Justice O’Connor was a former

partner), clerking was considered an advantage. Judges also feel it is important to

assist clerks in obtaining a job. It is also common to see clerks who summer at law firms

between their second and third year of law school and then return to those firms after

finishing clerkship. For students who are interested in litigation, clerkship is a definite

26

advantage because it offers a unique opportunity to learn and anticipate what judges

think about written and oral advocacy approaches. − O’Connor J.A (Oct/99)

Jobs are not a big concern. Clerks who summered at law firms between second and

third year of law school generally have the option of going back to the law firms they

worked for. Clerks seem to pursue a wide variety of career paths, including private

practice in Canada or the U.S., graduate studies, and business. Boutique litigation firms

tend to look very favourably upon Court of Appeal clerks. – UWO Grad and 1998/99

Clerk and (Nov/98).

27

ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE &

ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE–DIVISIONAL CRT

A.

INTRODUCTION

There are approximately 22 clerkships available and the Law Society of Upper Canada

recognizes these one–year contract positions as fulfilling the articling requirement. Two

clerkship positions are with the Superior Court of Justice – Divisional Court. Interested students

should refer to the next section to learn more about these positions.

Completed applications must be sent directly to the Court and received by their deadline.

B.

SALARY AND BENEFITS

Salary and benefits are the same from region to region. Law clerks are contract employees of

the Ministry of the Attorney General and are represented by the Association of Law Officers of

the Crown (ALOC). Benefits include vacation pay, statutory holiday pay, 4% pay in lieu of

benefits, paid sick days and an educational stipend. Law clerks are also included in the Ministry

of the Attorney General hireback pool and may apply for internal counsel positions after clerking

and completion of bar admission.

C.

DUTIES

Successful candidates will work closely with judges and become involved in many aspects of

the civil and criminal trial process. Law clerks are encouraged to attend trials, civil motions

court, jury selections, sentencing hearings, case conferences, bankruptcy hearings, summary

conviction appeals, and family court. The duties of clerks include the following:

providing judges with oral opinions and written memoranda of law on a broad range of legal

topics;

reviewing pleadings;

preparing case summaries;

assisting in drafting jury charges; and

editing judgments.

Law clerks may also be invited to assist judges in preparing scholarly work, speeches and

presentations on law–related topics.

In Toronto, for each three or four month period at the Court, each law clerk is typically assigned

to work for eight to ten full-time and supernumerary judges. The judges themselves are

assigned to various rotations, including family, criminal, commercial, and civil.

In Brampton, Hamilton, London, Newmarket, Ottawa, Sudbury, Thunder Bay and

Windsor, the clerks provide assistance to all of the judges sitting in the region. These clerks

are exposed to diverse areas of the law and have the opportunity to develop year–long working

relationships with the judges in their region.

28

All law clerks attend educational seminars throughout the year in which judges and senior

counsel are invited to engage in informal discussions with the clerks. The clerks participate in

selecting the speakers to be invited and the topics to be discussed. Law clerks have also

traditionally been invited to attend judges’ conferences and training is provided to clerks during

an initial two-day orientation session.

The Divisional Court clerks in Toronto provide legal research to the judges assigned to the

Divisional Court and prepare pre–hearing bench memoranda. The Divisional Court clerkship

appeals most to those who have a strong interest in administrative, labour, constitutional,

judicial review and appellate legal issues.

The Divisional Court is the main forum for legal challenges to government action. High profile

cases include the same-sex marriage case, school closing cases across the province, a case

challenging the “zero tolerance” regime for doctors who sexually abuse patients, the Polewsky

case dealing with small claims court fees, and a variety of important environmental cases.

D.

LOCATIONS

* Students interested in clerking at the Superior Court of Justice, but not specifically the

Divisional Court, may apply for one of the 22 positions referred to in the separate Court

advertisement. Candidates may apply for both Superior Court of Justice and Divisional

Court positions. If applying for both, please submit only one application but clearly

indicate which positions you are applying for and your order of preference.

Website Links:

http://www.ontariocourts.on.ca/scj/en/lawclerkprogram/articling.htm

http://www.ontariocourts.on.ca/scj/en/lawclerkprogram/articlingdiv.htm

There are approximately 10 positions available in Toronto, and a total of approximately 12

positions in the following centres:

Brampton (2),

Hamilton (2),

London (1),

Newmarket (2),

Ottawa (2),

Sudbury (1)

Thunder Bay (1) and

Windsor (1),

If applying for more than one location, candidates must indicate in their cover letters the

order of their preferred locations. **If applying for a Divisional Court position (see separate

job

advertisement:

http://www.ontariocourts.on.ca/scj/en/lawclerkprogram/articlingdiv.htm),

candidates must indicate their order of preference between Superior Court position(s)

and the Divisional Court position.

29

Candidates may apply for both the Superior Court of Justice and Superior Court of Justice –

Divisional Court positions. If applying to both the Superior Court of Justice and Superior Court

of Justice – Divisional Court, submit one application only that clearly indicates you are applying

to both and your order of preference.

While the majority of the Court’s work is done in English, qualified clerks have the opportunity to

work on cases heard in French. Candidates applying for the position in Ottawa must be fluent in

spoken and written French and English.

Clerks in Toronto enjoy offices downtown on the sixth floor of the court house at 361 University

Avenue, adjacent to the Judges’ Library and the Law Society’s Great Library in historic Osgoode

Hall. In the other regions, clerks maintain offices inside the regional court houses and have

access to both local law libraries and, with the assistance of the Toronto law clerks, the Toronto

law libraries. Each clerk is equipped with internet and Quicklaw access, and current computer

equipment and software.

E.

CAREER PROSPECTS

Clerks recommended for inclusion in the Ministry Hire–Back pool are eligible to apply for

restricted Crown Counsel Positions for one year following completion of the Licensing process.

F.

QUALIFICATIONS

The Court seeks applicants who possess strong academic records, excellent legal research and

writing skills, and the ability to produce high–quality work under strict deadlines. One of the 2

positions in Ottawa must be fluent in spoken and written English and French. Bilingualism is an

asset in the other regions. Some travel may be required for clerks working in regions outside

Toronto.

G.

THE APPLICATION

Please submit the following in triplicate by the deadline: Friday, January 28, 2011 by 5:00

p.m. The Court does not accept applications by email or by fax:

1. a covering letter indicating your preferred court location (or the order of preference if you are

applying for more than one location);

2. a current curriculum vitae;

3. official or photocopied transcripts of all university marks, including first semester of second

year law;

4. one legal writing sample (maximum 15 pages); and

5. two letters of reference referring to your legal research and communication skills.

Your application should be sent by mail or courier to:

Melissa Phillips, Counsel, Office of the Chief Justice

Superior Court of Justice

361 University Avenue, Room 621

Toronto, ON M5G 1T3

30

Tel: (416) 327–5005

Applications by e-mail or by fax will not be accepted.

For more information about the application process and the clerking program go to

http://www.ontariocourts.on.ca/scj/en/lawclerkprogram/articling.htm

H.

INTERVIEWS

Interviews will take place in March/April 2011 either in person or, where necessary, by

conference call. The Court does not pay travel costs to attend interviews. Note that law clerks

are contract employees of the Ministry of the Attorney General.

I.

APPLICATION AND INTERVIEW ADVICE FROM UWO STUDENTS, CLERKS,

PROFESSORS, AND VISITING JUDGES

Offers an unparalleled opportunity to observe advocacy, especially given there are fewer

opportunities now available to students and junior lawyers to observe courtroom

proceedings. Clerking also gives you the opportunity to know what judges think and how

they perceive different arguments. Clerks outside Toronto work for a large number of

judges and must be fairly organized and independent. – Leitch J. (Oct/99)

How busy you are depends a lot on which judges are sitting. You can definitely have a

life outside work. – 1998/99 Clerk (Oct/99)

At least half of the interview questions are about substantive points of law and your

research abilities.

o E.G. What is the best way to find the Airspace Act for New Brunswick? You must

also be able to articulate yourself well and persuade effectively. – 1998/99 Clerk

(Oct/99)

31

COUR D’APPEL DU QUÉBEC

A.

INTRODUCTION

Sous la direction du juge en chef du Québec, la Cour d'appel est composée de 19 juges puînés

ainsi que de quelques juges surnuméraires. La Cour d'appel siège à Québec et à Montréal,

généralement en formation de trois juges, exceptionnellement en formation élargie. Le plus

haut tribunal du Québec, la Cour d'appel agit en dernier ressort dans plus de 99% des affaires

qui lui sont soumises. Elle est la gardienne de l'intégrité et du développement du droit civil au

Québec. Sa vocation la distingue à cet égard des autres cours d'appel canadiennes.

Le service de recherche est composé d'environ 17 avocat(e)s-recherchistes à Montréal et 9 à

Québec. La Cour bénéficie des services d'un coordonnateur, qui voit au bon déroulement du

processus de sélection, assure la formation et l'intégration des nouveaux recherchistes au sein

de l'équipe et leur apporte un soutien juridique.

Les avocat(e)s-recherchistes sont, dans la majorité des cas, sélectionné(e)s un an avant leur

entrée en fonction; un concours est ouvert chaque année, en décembre et en janvier.

Tous/toutes les candidat(e)s sont tenu(e)s d'être admissibles au stage du Barreau lors de

l'embauche. L'emploi est d'une durée de deux ans, ce qui permet aux avocat(e)s-recherchistes

d'acquérir une importante expérience en droit dès le début de leur carrière. Les 6 premiers

mois sont reconnus par le Barreau du Québec à titre de stage de formation professionnelle.

Completed applications must be sent directly to the Court and received by their deadline.

B.

UN POSTE STIMULANT ET FORMATEUR

Dès son arrivée, l'avocat(e)-recherchiste est assigné(e) à un juge avec lequel il/elle travaillera

pendant tout son séjour à la Cour et avec lequel il/elle développera une relation privilégiée. Une

bonne partie du travail se déroule avant l'audition des pourvois, l'avocat(e)-recherchiste devant

analyser en profondeur les dossiers qui lui sont confiés dans le but de formuler une opinion

juridique et d'assurer un soutien au juge sur chacune des questions en litige. Position d'autant

plus intéressante qu'elle permet de bien comprendre la nature des fonctions d'un magistrat.

L'avocat(e)-recherchiste assiste aux auditions des dossiers sur lesquels il/elle a travaillé. Il/Elle

peut ainsi examiner d'un point de vue critique le déroulement de l'audience. Si le dossier est

mis en délibéré, il/elle peut être amené(e) à réaliser des recherches supplémentaires. Ainsi,

il/elle suit le cheminement des dossiers jusqu'à ce que jugement soit rendu. Le stage offre donc

une occasion unique de travailler dans les coulisses du système judiciaire et de se familiariser

avec son fonctionnement.

De plus, un stage à la Cour d'appel permet de toucher à une variété de domaines : droit

constitutionnel, droit criminel, droit administratif, droit civil, droit des affaires, etc. Grâce à cette

diversité, les avocat(e)s-recherchistes acquièrent une polyvalence inestimable, des

connaissances approfondies et une précieuse expérience pratique sur la façon de mener à bien

un dossier de litige. Une étude rapide des emplois occupés par les avocat(e)s-recherchistes à

la suite de leur passage à la Cour d'appel montre que ceux-ci/celles-ci travaillent dans une

multitude d'organisations, que ce soit :

32

Cabinets d'avocats de toute taille;

Fonction publique québécoise ou fédérale;

Avocat de la défense ou du ministère public (droit criminel);

Organismes gouvernementaux ou paragouvernementaux;

Contentieux d'entreprises;

Milieu universitaire; etc.

Des ententes avec l'Université Laval et l'Université de Montréal permettent aux avocatsrecherchistes d'obtenir des crédits d'équivalence aux fins de certains programmes de maîtrise

(stage de recherche, travaux de recherche juridique réalisés dans le cadre de leurs fonctions).

Pour avoir plus d'informations sur ces ententes, nous vous invitons à vous adresser à un

représentant du Service de recherche de la Cour d'appel.

Celles et ceux qui sont désireux(ses) de relever le défi d'un emploi stimulant sont invité(e)s à

soumettre leur candidature au siège de la Cour à Montréal, à celui de Québec ou aux deux.

Lorsqu'un concours est ouvert, un avis est affiché sur les sites Web de la Cour d'appel et de

l'École du Barreau du Québec ainsi que dans les divers centres de développement

professionnel des facultés de droit.

C.

COMPÉTENCES RECHERCHÉES

La Cour recherche des candidates et des candidats qui possèdent un très bon dossier scolaire

ainsi que des aptitudes à la recherche et à la rédaction; ils/elles doivent également faire preuve

de maturité et d'autonomie dans l'exercice de leurs fonctions. Ils/Elles doivent maîtriser le

français et l'anglais.

D.

START DATE AND TERM OF EMPLOYMENT

As noted above, clerkships with the Court of Appeal of Quebec last two years. Most clerkships

will begin in January or June 2012. However, there is a certain amount of flexibility depending

on the needs of the Court. The Court will take into account the availability of the applicant

during the interview. If possible, it will try to accommodate the desires of each applicant.

E.

LE DOSSIER

Le dossier doit être soumis avant le début février, 2011. Though not a signatory to the Entente

de recrutement, the deadline for the Cour d’appel normally corresponds with the Course aux

stages recruitment process in Montreal.

Le dossier de candidature doit comprendre les documents suivants :

1. Lettre de présentation justifiant l'intérêt pour le poste;

33

2. Curriculum vitae;

3. Relevés officiels des notes (les photocopies de relevés officiels des notes sont

acceptées) :

a) CÉGEP (pour celles et ceux qui n'ont pas encore obtenu de diplôme universitaire);

b) Universités (les relevés de notes de toutes les études universitaires);

c) École du Barreau (si programme complété);

4. Deux lettres de recommandation (dont l'une, dans la mesure du possible, d'un

professeur de droit);

5. Un travail de rédaction juridique réalisé dans le cadre des études en droit;

6. Une preuve de statut de résidant(e) permanent(e), le cas échéant.

Le dossier de candidature doit être soumis à l'une ou l'autre des adresses ci-dessous ou aux

deux endroits, le cas échéant :

Montréal

Madame Arlette Raymond

Cour d'appel du Québec

100, rue Notre-Dame Est, bureau 3.60

Montréal (Québec) H2Y 4B6

Téléphone : 514 393-2040 poste 51246

Télécopieur : 514 864-4662

Courriel : araymond@judex.qc.ca

Québec

Madame Diane Simard

Cour d'appel du Québec

300, boul. Jean-Lesage, bureau 4.59

Québec (Québec) G1K 8K6

Téléphone : 418 649-3432

Télécopieur : 418 266-0374

Courriel : dianesimard@judex.qc.ca

All 2012 – 2014 articling applications must be received by early February 2011.

F.

POUR PLUS D’INFORMATIONS

For the most up-to-date information and deadlines, interested candidates should consult:

http://www.tribunaux.qc.ca/c-appel/Stage/stage.html

Pour de plus amples renseignements concernant le service de recherche, veuillez

communiquer avec:

Me Pascal Pommier, coordonnateur

Téléphone: 514-393-2040 poste 51370

Courriel: pascal.pommier@justice.gouv.qc.ca

34

BRITISH COLUMBIA COURT OF APPEAL &

BRITISH COLUMBIA SUPREME COURT

A.

INTRODUCTION

The British Columbia Judicial Law Clerk Program was established in 1973. One of the original

aims of the program was to improve the quality of advocacy in the province. Since that time it

has fulfilled its original mandate and has continued to expand its objectives.

For 2012-2013, 30 full-time law clerks will be hired for the two superior courts. The Court of

Appeal will employ 12 law clerks. The Supreme Court will employ 18 law clerks: 2 law clerks will

be located in Victoria, 3 law clerks will be located in New Westminster, and 13 law clerks will be

located in Vancouver. Most Court of Appeal clerkships are for 10 months (September through

June), although some spaces are available for 11 or 12–month clerkships. The Supreme Court

clerkships are for 12 months (September through August).

The time spent as a law clerk partially fulfills the articling requirements for call and admission to

the Law Society of B.C. After completing the clerkship, students must apply to the Law Society

for a reduction of the articling period. Law clerks typically complete their articling requirements

with a law firm, the Ministry of the Attorney General or the Department of Justice. All of these

employers support participation in the Judicial Law Clerk Program. Generally speaking, the

time frame for admission to the bar for students who have been law clerks in B.C. is 18 to 22 ½

months following graduation from law school.

Completed applications must be sent directly to the Court and received by their deadline.

B.

SALARY AND BENEFITS

Law clerks with the British Columbia courts are auxiliary employees of the provincial Ministry of

the Attorney General. The salary for the law clerk position is comparable to the salary of