Skaaning (2009b)

advertisement

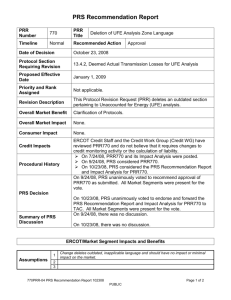

Measuring the Rule of Law Svend-Erik Skaaning, Assistant Professor, PhD Department of Political Science, University of Aarhus, Denmark skaaning@ps.au.dk 1 Measuring the Rule of Law Abstract This article offers a comparative review of seven rule of law measures. The assessment demonstrates that the differences are not only a question of form, but also of appropriateness. The shortcomings are, among others, restrictions in scope and availability of disaggregate data, insufficient codebooks, and unjustified aggregation procedures. Moreover, the indices tap into two different if related dimensions: quality of the legal system and societal order. Finally, statistical analyses show that if different indices are employed, the results change significantly. These findings suggest that more precaution is required in the development and employment of rule of law measures. Keywords: rule of law; measurement; dataset assessment 2 Introduction Since the end of the Cold War, efforts to advance the rule of law have accompanied democracy promotion for both personal security reasons and to support political and economic development. Governance reform programs initiated by international financial institutions and national aid agencies have emphasized rule of law as a key component for human welfare, stability, and growth (Haggard et al. 2008, 206; Carothers 1998; 2006). Naturally, the issue has also received significant attention in social scientific research, and many scholars have turned to quantitative rule of law measures to facilitate their studies (e.g. Andrews and Montinola 2004; Apodaca 2004; Barro 1997; 2000; Joireman 2001; 2004; Rigobon and Rodrick 2005). The development of governance indicators advances our ability to monitor differences and changes in the quality of government across space and time. However, while rule of law violations around the world underline the existence of human rights problems, the creation of good measures is not straightforward. Such efforts only signify a step forward if the development is followed by careful attention to the value of the data in terms of their reliability, validity, and equivalence. However, in contrast to the measurement of democracy (cf. Bollen 1993; Bollen and Paxton 2000; Hadenius and Teorell 2005; Lauth 2004; Munck and Verkuilen 2002), no one has yet stepped back and systematically taken stock of the conceptualization and operationalization of the different rule of law indices framing such analyses. The present article addresses this neglected issue and provides a comparative review of seven up-to-date indices (see table 1 below) that reflect, according to their users and generators, the de facto level of rule of law in many different countries.1 The measures are provided by five organizations. The first is made available by the private operating Bertelsmann Foundation2 (BF). The work of the German foundation is funded mainly by income earned from its shares in the media corporation Bertelsmann AG. Its rule of law measure is part of a larger dataset, which is compiled to investigate the level and conditions of – and to advance – constitutional democracy combined with a socially responsible market economy. Similarly, Freedom House3 (FH) explicitly supports the expansion of freedom in the world. Freedom House4 is an independent nongovernmental organization with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It relies on grants and donations from private organizations and government agencies, first and foremost the US State Department, and is responsible for no less than three of the 3 indices linked to three different projects, namely Freedom in the World (FW), Countries at the Crossroads (CC), and Nations in Transit (NT). Global Integrity5 (GI) is another independent, non-profit organization placed in Washington, D.C. It is financed by a diverse mix of charitable foundations, governments, multilateral institutions, and the private sector. The aim of Global Integrity is to produce information on governance and corruption trends in order to improve democratic and accountable political rule. The Global Integrity index of rule of law and access to justice is included in a wider dataset on national-level anti-corruption mechanisms. The only rule of law measure, included in this review, that is supplied by a for-profit organization, the US-based Political Risk Services Group6 (PRS), is the law and order index that constitutes a fraction of the International Country Risk Guide (Political Risk Ratings). The PRS only aims to provide a comparative assessment of the political stability of the countries covered and not to improve governance around the world. In this respect, it differs from the other data generators, including the World Bank7 (WB) that has compiled the final measure put under direct scrutiny, namely the rule of law indicator from the Worldwide Governance Indicators dataset. The first part of the assessment of these indices follows the different steps of dataset assessment suggested by Gerardo Munck and Jay Verkuilen (2002). Hence, the article proceeds in five parts. The first four concern the indices’ focus and scope, conceptualization, measurement, and aggregation. The fifth evaluates whether the differences in measurement involve differences in the result when the rule of law indices are substituted for each other as dependent variables in crossnational analyses. Focus and Scope Even though all the measures share a common focus on the rule of law, they are also marked by significant differences. One is whether the scores exclusively concern violations of rule of law committed by the government/state or if the assessments also take the society’s overall situation into consideration. Both possibilities are legitimate, but the focus depends on the particular research question, and therefore also which measure is more suitable. The scores provided by three measures – BF, GI, and one of the Freedom House ratings (CC) – only reflect the practices of the government/state and its agents. The WB and PRS indicators provide an evaluation of the general rule of law condition, while the other two Freedom House measures, FW and NT, take an 4 intermediate position; they focus predominantly, but not exclusively, on violations committed by the government/state. The information gathered in table 1 shows that none of the datasets contain scores for any years before 1984 and that more than half of them just cover four years or less. However, many of the indices show rather impressive country coverage. FW and WB simply cover all independent countries and some more or less autonomous territories. The people behind GI have the same intention, but countries are tentatively chosen according to three criteria: availability of experts and balance with regard to geography and basic freedom and civil liberties. Table 1 about here PRS is not linked to an explicit principle concerning the inclusion of countries. Nonetheless, it tends to be somewhat biased towards rich and large countries, 8 while the novel and bi-annual BF is limited to all developing and transformation countries with more than two million inhabitants. CC and NT also focus on transformation countries. CC covers 60 countries around the world that Freedom House considers to be strategically important and at a critical crossroads in determining their political future; half of the countries are evaluated in odd years, half in even years. NT just covers all the former Communist states of Europe and Eurasia, except Mongolia. As the scope of the datasets is restricted in time and space, their value and relevance for particular research questions are limited. Especially the ability to track back in time the developments in respect for the rule of law is severely restricted. For example, none of the indices cover the whole period of the third wave of democratization (since 1975), not to speak of the postWWII era; to mention just two demarcations often used in diachronic, empirical research. Furthermore, not all measures support direct comparisons with experiences of rich, long-enduring democracies (primarily OECD members) and/or small countries. Thus, more effort is certainly needed in expanding rule of law measures back in time. On the other hand, the scope limitations lower the risk of conceptual stretching (cf. Sartori 1970). Conceptualization Regarding the attributes and their components, which the data generators have associated with rule of law, the concept is rather stretched as many different aspects are emphasized. But even though it is doubtful whether there is a correct specification, all definitions and specifications are not equally 5 reasonable. They can be either too maximalist or too minimalist, or they can be infected by redundancy and conflation (Munck and Verkuilen 2002, 9-13). As to the definition of rule of law, one way to address the different conceptualizations is to compare them with theoretically well-grounded classifications. According to Lon Fuller, in a country characterized by the rule of law, the law should fulfill several criteria: generality, publicity, prospectivity, clarity, non-contradictoriness, capability of compliance, stability, and congruence between declared rules and the acts of administrators (1981, 158; cf. Raz 1977, 196). In a discussion of previous attempts to reveal common principles associated with the concepts of constitutionalism, Rechtsstaat, and the rule of law, Hans-Joachim Lauth (2001, 33) recognizes these eight attributes. But he expands on the list even further to cover the fourteen attributes shown in table 2. Table 2 about here There are good reasons to acknowledge these elements as parts of the core concept. Even though the number of defining attributes appears rather overwhelming, they do not, by far, constitute an exhaustive list of all the elements that have been linked to the rule of law in legal and social scientific research. This is illustrated by the conceptual overview of all the indices shown in appendix A. It demonstrates the presence of interesting similarities as well as differences among the constitutive elements. Compared to the attributes presented in table 2, none of the measures cover all of them, at least not explicitly. While most measures emphasize judicial independence and equality before the law, the questions of whether the laws are publicly promulgated, clear, comprehensive, coherent, and stable are hardly addressed. On the other hand, quite a number of supplements to the list are also present among the attributes. As a result, it is possible to distinguish between at least three clusters of attributes, that is, conceptual dimensions of the rule of law. One dimension concerns the general quality of the legal system, where an independent and impartial judicial system with high integrity, respect for the decisions of the courts, due process, and equality before the law make up core attributes. A second dimension addresses the extent to which personal integrity rights, such as freedom from arbitrary arrests, police violence, and inhuman/degrading treatment, are violated by the government. Finally, a third dimension covers features related to whether order or open conflict, violence, upheavals, and crime characterize a country. Whereas all measures consider the functioning of the legal system, GI is the only dataset to focus exclusively on the first dimension. The practice of the legal system is the principal focal point 6 of four other indices, namely BF, CC, NT, and FW, out of which only the latter addresses order besides personal integrity rights. PRS pays attention to the legal system’s strength and impartiality and public respect for law obedience. The same applies to the covering of personal integrity by WB. One would think that the more dimensions an index captures, the higher the risk of maximalist conceptualizations. This is, however, not necessarily so. Actually, some of the most blatant examples of maximalism are not caused by a multidimensional view. One of the attribute components associated with FW demands an effective and democratic control of law enforcement officials. Likewise, NT emphasizes the importance of legislation that provides protections for fundamental political, civil, and human rights in addition to the state’s and nongovernmental actors’ respect for all of these fundamental rights in practice. In both cases, the conceptual domain of rule of law shows a considerable overlap with that of democracy.9 You can also question whether the level of crime and violence (PRS,10 WB), protection of property rights (CC, WB), and agents’ confidence in the rules of society (WB) should be constitutive parts of the rule of law concept. In general, one should not include attributes under the same conceptual umbrella if they are likely to be causally related. Regarding redundancy, the measures explicitly distinguish between different levels of abstraction; WB and NT only operate on two levels, though. The providers of the other indices have made efforts to sort the attributes and attribute components systematically, but they have not been equally successful in doing so. CC provides at least three redundant attribute components. For instance, if all persons are entitled to equal protection under the law, and all persons are equal before the courts and tribunals, then it is not possible to discriminate on the grounds of gender, ethnicity, or sexual orientation in the legal system.11 Similarly, concerning BF, if the separation of powers works, it means that the judiciary is independent. As to the problem of conflation, GI offers an illustration of the problem when it places the rather specific attribute ‘Judges are safe when adjudicating corruption cases’ on the same abstraction level as (e.g.) ‘Citizens have equal access to the justice system’. The conceptual bounds of the rule of law are obviously unsettled. The term ‘rule of law’ is certainly ‘used in a plethora of ways, often with different and even contradictory implications for both research and policy’ (Haggard et al. 2008, 220-221). An equivalent to the widely acknowledged – although disputed – definition of democracy (polyarchy) by Robert Dahl (1989, 221) has not yet been established. But the best answer to the problem is not necessarily to abandon the concept altogether and commence on a more disaggregated approach; only to focus, for 7 example, on judicial independence (Ríos-Figuera and Staton 2008). Much leverage can be gained by strengthening the conceptualization of the key concept that is here to stay, although essentially contested (Waldron 2002). In any case, researchers should pay attention to the conceptualization underlying the measures, since some of them may fit their research questions better than others. It can make a significant difference whether one is interested in, say, the security of persons or businesses. This final comment on the conceptualization is also worth keeping in mind when we move on to the question of measurement. Measurement A clarification of the conceptual landscape is a prerequisite for proper measurement; that is, the operationalization of the rule of law. A codebook is necessary in order to record and make public the rules and choices guiding the coding process and to increase consistency, transparency, and replicability. As the quality of available information is often questionable and inconsistent across nations, over time, and vis-à-vis different aspects (cf. Bollen 1992, 189), it is extra important to establish equivalence through firm guidelines. As shown in table 3, all measures base their scores on a broad range of information. Information on the condition of rule of law is calibrated into numerical values according to predetermined sets of coding standards. This kind of subjective measurement has been heavily disputed because reliability problems are likely to arise owing to random and systematic measurement errors introduced by the raters who interpret the sources differently. Then again, rule of law and all its key traits are very difficult to measure through objective indicators, and the validity of the measures should generally have the highest priority (Munck and Verkuilen 2002, 18). The Freedom House measures and BF stand out for their narrative country reports, which accompany their numerical assessments, while GI takes the lead when it comes to a detailed description of the circumstances, sources, and review comments that have influenced the score of each component. Table 3 about here Even though a comprehensive coding manual is warranted, the Freedom House codebooks (FW, CC, NT) consist of little more than checklists defining the parameters of the indicators combined with mere standard descriptions of how to interpret the numerical scores assigned to the cases.12 8 Furthermore, the checklists used in the data construction have undergone changes over the years, meaning that the diachronic, internal consistency of the scores is questionable. The guidelines outlined in the codebooks of BF and GI have become increasingly detailed, so that they now represent good backgrounds for the coding process. In contrast, it is questionable whether an outright PRS code manual even exists. According to the generator, the scores are assigned based on a series of pre-set questions for each component. However, neither the list of questions nor information on the methodology are made available, and both are likely to be inadequate. As to the use of coders, all datasets are based on the work of more than one coder to support intercoder reliability. Furthermore, in all cases except PRS, the scores are based on assessments made by “experts” rather than students, and the data are scrutinized through comprehensive review processes. Despite these positive features, however, statistical interrater reliability tests are missing. The overall percentage of agreement13 (or near-agreement) was published for the overall BF dataset, but only for the 2003 assignments. Among the guidelines found in the codebooks, we are often presented with the range and graduation of numerical scores to be assigned. Mostly the measurement levels of the examined measures are neither theoretically justified nor attached to discussions directed towards maximizing homogeneity within classes using a minimal number of distinctions (cf. Munck and Verkuilen 2002, 17-18). Variance truncation could pose a problem concerning the attribute components of GI and PRS, because of crude measurement scales. On the other hand, the more fine-grained options linked to the other measures are not unproblematic either; they make it more demanding to define criteria for each point and more difficult for the coders to employ them consistently. Aggregation When the process of assignment is concluded, researchers often combine the disaggregate scores into overall indices. But this analytical step is usually not founded in theoretical and empirical justification, and the rule of law measures do not deviate from this trend. The data providers do not base their aggregations on explicit theory about the relationship between the attributes, just as they do not test the empirical dimensionality of their datasets in any systematic way. 14 I have therefore carried out such tests myself, and the results (not reported) indicate that CC and BF are unidimensional and that GI is not. Unfortunately, the data generators of the remaining measures do not score the cases on a low level of abstraction, despite a working definition that disaggregates the main concepts (NT).15 Or 9 they do not make their lower-level data publicly available, even if requested (FW, PRS). In this way, these measures only allow their users to discriminate between countries according to their overall rule of law score without the possibility of digging a bit deeper into interesting relationships or making use of alternative aggregation procedures. It is telling that – despite the missing theoretical (and empirical) establishment of links between the constitutive attributes – all use the same aggregation rule, namely taking the simple average at the component level. Apparently, examinations of alternative aggregation procedures, such as weighting the features differently or to consider some of them as either necessary or sufficient (cf. Goertz 2006), have not been considered. Comparisons of competitive indices linked to similar concepts have often been limited to simple correlation tests, to clarify whether they tend to tap into the same latent phenomenon. Following up on this tradition, table 4 presents the bivariate correlations between the rule of law indices under scrutiny. The differences in conceptualization, sources, coding, and so on manifest themselves in some of the associations, but not all of them show the very high values one would expect from measures meant to reflect the same concept, at least in name. The correlation between CC and PRS even displays the opposite direction of the expected. Broadly speaking, CC, NT, and GI show the lowest statistical association with the other measures, whereas FW, WB, and – less so – BF are more strongly related with their rivals. Table 4 about here A closer look at the correlations indicates that the measures represent more than one principal dimension. The same impression evolves from a rotated factor analysis, which includes the four measures covering most countries and concerns the data from one of the only overlapping years (i.e. 2005). The results show two principal factors with eigenvalues above 1, explaining 68 per cent and 26 per cent of the variation, respectively. The first component tends to reflect the legal system’s quality, and it seems reasonable to understand the second as representing societal order, which would be in accordance with the distinctions suggested above in the section on conceptualization. WB is equally associated with both dimensions. This finding is not surprising because it reflects the fact that all the data from the original measures are used in the construction of WB, and that it is based on a very broad definition and range of sources. Do the Differences Matter? 10 The many differences and similarities in the conceptualizations and measurements of rule of law naturally intrigue our curiosity of what would happen if these measures were employed interchangeably. It has recently been stated that robustness checks are particularly important when making claims about the effects of rule of law (Haggard et al. 2008, 222). Other researchers have already begun to take up this task (Ríos-Figuera and Staton 2008, 19-22). However, no checks on the solidity of the causes of the rule of law have so far been carried out. Thus, the four indices with the widest country coverage are used interchangeably to represent the dependent variable in two analyses. The first is a replication study of an interesting study by Sandra Joireman (2004), in which she used an institutional approach to investigate whether and how much the legal system influences the degree to which countries are characterized by the rule of law. More specifically, the hypothesis tested was whether common law systems show a better performance in this respect than civil law systems, as it has been suggested in the literature (cf. Hayek 1973; Eisenberg 1988; La Porta et al. 1999). Relying on the PRS measure, Joireman found that the proposition is only supported in those countries that have been colonized. The replication analysis employs the same method as the original study, namely the MannWhitney U-test. However, while Joireman focuses on the average rule of law level across years, the huge differences in diachronic coverage make it more suitable to focus on the scores for 2005, which is one of the two years of common coverage. Moreover, to increase the country coverage, the data used to distinguish common law from civil law countries, on the one hand, and between formerly colonized countries and those not colonized, on the other, come from La Porta et al. (1999).16 The findings, presented in table 5, demonstrate a significant difference in respect for the rule of law between common law and civil law countries if the WB or FW measures are used. However, the opposite conclusion is derived if we pin our faith on the PRS or BTI scores. Moreover, the same patterns in results emerge if the analysis only includes former colonies. This means that the differences in rule of law measurement do in fact make a difference, and the main conclusion of the original study by Joireman does not rest on solid empirical ground. Table 5 about here 11 In the second analysis, the same four measure are used interchangeably as dependent variables, but another method is employed, that is, multiple OLS-regression. Furthermore, the model is expanded with additional explanatory factors used in other rule of law studies. These are: oil production (Barro 2000; Hansson and Olsson 2006), wealth (Barro 2000; Joireman 2004), country size (Hansson and Olsson 2006), ethno-religious fractionalization (Hayo and Voigt 2005; Weingast 1997; Hansson and Olsson 2006), communist past (Hoff and Stiglitz 2004; Sandholz and Taagepera 2005), and religion (Barro 2000; Hayo and Voigt 2005). The operationalization of the independent variables is presented in appendix B. Finally, to see whether the results depend on the case coverage, regressions are run for all countries and the countries included in all four datasets, respectively. The year in focus is still 2005. The results of the multiple regressions are summarized in table 6. A few explanatory variables consistently show a significant (oil production, wealth) or non-significant (ethno-religious fractionalization, common law) association with rule of law. On the other hand, the results linked to the remaining variables demonstrate interesting dissimilarities across case coverage and/or rule of law indices. For example, lifting the restriction of common inclusion of cases means that the variable Protestant turns significant for the WB and PRS indices, and insignificant for the BTI measure. Likewise, the inclusion of more countries means that communist past tends to have a negative rather than no impact on the rule of law, if the latter is measured by WB or FW Table 6 about here Not only do we see differences in whether the relationships are significant or not, the significant associations for some variables (colonized, communist past, Muslim) even show opposite directions. In other words, the association of the explanatory variables with rule of law ranges from positive over non-existing to negative, depending on the index used to operationalize the rule of law. Also worth mentioning are the positive, significant associations between the PRS index and communist past as well as Muslim, which contradict the theoretical expectations. Taken together, the mixed findings for many of the variables indicate that the results are not very robust. Previous general studies exploring the sources of rule of law have only used a single rule of law index. Their conclusions have thus depended heavily on the reliability and validity of the scores employed. The results from this study indicate that this problem is far from trivial, as the differences in measurement and coverage of the rule of law indices have considerable consequences 12 for the substantial findings – and much more so than in the related field of democratization studies (cf. Bollen and Paxton 2000; Casper and Tufis 2003; Hadenius and Teorell 2005). Conclusion The review of seven rule of law measures has lent support to some general conclusions. First, the indices differ significantly on all the parameters addressed in this article, that is, focus and scope, conceptualization, measurement, aggregation, and association with suggested explanatory factors. The assessment also demonstrated that often the differences were not equally (im)plausible. In general, the justifications made in relation to the index constructions were inadequate. Among the particular shortcoming were: considerable restrictions in the coverage of years and countries, conceptual pitfalls in the form of redundancy and weak theoretical foundation, limitations in the creation and availability of disaggregate data, insufficient codebooks, and missing references to sources undermined the operationalizations. As regards the aggregation procedures, they were characterized by the default option of using unweighted averages rather than being grounded in theory and tests of empirical dimensionality. In fact, the rule of law measures empirically (and conceptually) tapped into at least two distinct dimensions; one is reflecting the quality of the legal system and the other is capturing the level of order in society. The considerable differences were also underlined by replication studies and a multiple-regression analysis, which showed that replacing the rule of law measures – as the dependent variable – changed the results significantly. Future research can benefit in three ways from the explications and critical points put forward in this assessment. First, the findings provide implicit and explicit suggestions for improving the existing measures. Second, we can learn from the advantages and disadvantages of previous measures when we set out to construct new datasets and indices related to good governance in general and rule of law in particular. Third, the shortcomings of – and differences in – the leading measures call for re-examinations of the many studies that, in one way or another, have used them as rule of law indicators. All in all, the findings suggest that we have to be more careful when developing and applying rule of law indicators, but not that we should give up our search for better measurement tools. 13 Appendix A: Attributes Linked to the Rule of Law Measures Measure Attributes Attribute Components Rule of Law (BF) Checks and balances Working separation of powers Independent judiciary Legal or political penalties for power abusing officials Civil rights Protection of civil liberties and possibility of seeking redress for violations Independent judiciary Judiciary not subject to interference Judges appointed and dismissed in a fair and unbiased manner Judges rule fairly and impartially Governmental authorities comply with judicial decisions which are enforced Private concerns comply with judicial decisions which are enforced Rule of law in civil and criminal matters Protection of defendants’ rights, including presumption of innocence Access to independent, competent legal counsel Fair, public, and timely hearing by competent, independent, and impartial tribunal Prosecutors independent of political control and influence Prosecutors independent of powerful private legal/illegal interests Effective and democratic control of law enforcement officials Law enforcement officials free from the influence of non-state actors Protection from political terror, unjustified imprisonment, exile, torture, and freedom from war and insurgencies No arbitrary arrests and detentions and no fabrication or planting of evidence No beating of detainees or use of excessive force or torture Conditions in pretrial facilities and prisons humane Citizens have means of effective petition and redress Population not subjected to physical harm, forced removal etc. due to conflict/war Laws, policies, and practices guarantee equal treatment Various distinct groups have equality before the law Violence against such groups not widespread and perpetrators brought to justice No legal/de facto discrimination in employment, housing etc. against such groups Women enjoy full equality in law and practice Non-citizens enjoy basic human rights Independent judiciary Independent, impartial, and non-discriminating administration of justice Judges/magistrates protected from interference by executive and legislative Governmental authorities comply with judicial decisions Judges appointed, promoted, and dismissed in a fair and unbiased manner Judges appropriately trained Primacy of rule of law in civil and criminal matters Presumption of innocence Fair, public, and timely hearing by competent, independent, and impartial tribunal Rights and access to independent counsel Access to independent counsel if beyond means when serious felonies Prosecutors independent of political direction and control Public officials and ruling party actors prosecuted for abuse of power Accountability of security forces and military to civilian authorities Effective and democratic control of the police, military, and security service Police, military, and security services refrain from interference in politics Police, military, and security services accountable for abuses of power Members of police, military, and security services respect human rights Protection of property rights Right to own property alone and in association with others Adequate enforcement of property rights and contracts Protection from arbitrary/unjust deprivation of property Equal treatment under the law All persons entitled to equal protection under the law All persons equal before the courts and tribunals No discrimination on the grounds of gender, ethnicity, or sexual orientation Rule of Law (FW) Rule of Law (CC) Legislation provides protections for fundamental political, civil, and human rights Judicial Framework and Independence (NT) The state and nongovernmental actors respect fundamental rights in practice Independence and impartiality in the interpretation and enforcement of constitution Equality before the law Effective reform of the criminal code/criminal law 14 Suspects and prisoners protected in practice against arbitrary arrest, detention without trial, searches without warrants, torture, and abuse, and excessive delays in the criminal justice system Judges are appointed in a fair and unbiased manner, and they have adequate legal training before assuming the bench Judges rule fairly and impartially, and courts are free of political control and influence Legislative, executive, and other governmental authorities comply with judicial decisions, and judicial decisions are enforced effectively Appeals mechanism for challenging criminal judgments Judgments in the criminal system follow written law Judicial decisions are enforced by the state Rule of Law and The judiciary is able to act Access to Justice independently (GI) Judges are safe when adjudicating corruption cases Law and Order (PRS) In law, there is a general right of appeal In practice, appeals are resolved within a reasonable time period In practice, citizens can use the appeals mechanism at a reasonable cost In practice, judgments in the criminal system follow written law In practice, judicial decisions are enforced by the state In law, the independence of the judiciary is guaranteed In practice, national-level judges are protected from political interference In law, the distributing cases to national-level judges is transparent and objective In law, national-level judges protected from removal without relevant justification In practice, no judges physically harmed because of adjudicating corruption cases In practice, no judges killed because of adjudicating corruption cases Citizens have equal access to the justice system In practice, judicial decisions are not affected by racial or ethnic bias In practice, women have full access to the judicial system In law, provision of legal counsel for defendants who cannot afford it In practice, provision of adequate legal counsel for defendants who cannot afford it In practice, citizens with median yearly income can afford to bring a legal suit In practice, a typical small retail business can afford to bring a legal suit In practice, all citizens have access to a court of law, regardless of location Law Strength and impartiality of the legal system Order Popular observance of the law Agents have confidence in the rules of society Agents abide by the rules of society High quality contract enforcement Rule of Law (WB) High quality police High quality courts Low likelihood of crime Low likelihood of violence 15 Appendix B: Operationalization of Explanatory Factors Oil production. Oil production is operationalized by using IMF’s (2007) list of hydro-carbon rich countries (2000-2005) found in the Guide on Resource Transparency. These countries rely heavily on oil production for government revenues and receive the value of 1 and the rest a 0 meaning that the variable is treated as a dichotomy. Wealth. Wealth is measured by a standard wealth indicator, namely (natural log of) GDP per capita (PPP) using data from the Penn World Tables for the year 2004. Country size. The (natural) log of a country’s total area in square kilometres is used to measure this variable, based on data from the World Development Indicators provided by the World Bank (2008). Ethno-religious fractionalization. Data on the degree of heterogeneity are taken from Alesina et al. (2003), who have constructed scores of ethnic and religious fractionalization. The values of the indices correspond to the probability that two randomly selected people belong to different ethnic and religious groups, respectively; meaning that a high value on the index corresponds to a high degree of fractionalization in a given country (2003, 158-160). As the same logic applies to both ethnic and religious fractionalization, a combined measure has been constructed based on the maximum value of the two original indices for each country. Communist past. A dummy variable for communist and post-communist countries has been constructed. Dominant religion. Following the procedure used by M. Steven Fish (2002), two dummy variables have been created distinguishing between countries where Islam and Protestantism are the dominant (plurality or majority) religions, respectively. 16 References Alesina, Alberto, Arnaud Devleeschauwer, William Easterly, Sergio Kurlat, and Romain Wacziarg. 2003. Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth 8:155-94. Andrews, Josephine T., and Gabriella R. Montinola. 2004. Veto Players and the Rule of Law in Emerging Democracies. Comparative Political Studies 37:55-87. Apodaca, Clair. 2004. The Rule of Law and Human Rights. Judicature 87:292-99. Barro, Robert (1997). Determinants of Economic Growth: A Cross-Country Empirical Study. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. Barro, Robert. 2000. Rule of Law, Democracy, and Economic Performance. In 2000 Index of Economic Freedom, eds. Gerald P. O’Driscoll Jr., Kim R. Holmes, and Melanie Kirkpatrick. Washington and New York: Heritage Foundation and Wall Street Journal. Bollen, Kenneth A. 1992. Political Rights and Political Liberties. In Human Rights and Statistics: Getting the Record Straight, ed. Thomas B. Jabine, and Richard P. Claude. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Bollen, Kenneth A. 1993. Liberal Democracy: Validity and Method Factors in Cross-National Measures. American Journal of Political Science 37:1207-30. Bollen, Kenneth A., and Pamela Paxton. 2000. Subjective Measures of Political Democracy. Comparative Political Studies 33:58-86. Carothers, Thomas. 1998. The Rule of Law Revival. Foreign Affairs 77:95-106. Carothers, Thomas. 2006. Promoting the Rule of Law Abroad: The Search for Knowledge. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Casper, Gretchen, and Claudio Tufis. 2003. Correlation versus Interchangeability: The Limited Robustness of Empirical Findings on Democracy using Highly Correlated Datasets. Political Analysis 11:196-203. Chomsky, Noam, and Edward S. Herman. 1988. Manufacturing Consent. New York: Pantheon Books. Dahl, Robert A. 1989. Democracy and Its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press. Eisenberg, Melvin A. 1988. The Nature of the Common Law. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Fish, M. Steven. 2002. Islam and Authoritarianism. World Politics 55:4-37. 17 Fuller, Lon L. 1981. The Principles of Social Order. Durham: Duke University Press. Goertz, Gary. 2006. Social Science Concepts: A User’s Guide. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Hadenius, Axel, and Jan Teorell. 2005. Assessing Alternative Indices of Democracy. IPSA Committee on Concepts and Methods Working Paper Series (Political Concepts No. 6). Haggard, Stephan, Andrew MacIntyre, and Lydia Tiede. 2008. .“The Rule of Law and Economic Development. Annual Review of Political Science 11:205-34. Hansson, Gustav, and Ola Olsson. 2006. Country Size and the Rule of Law: Resuscitating Montesquieu. Working Paper 200, School of Economics: Göteborg University. Hayek, Friedrich A. 1973. Law, Legislation, and Liberty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Hayo, Bernd, and Stefan Voigt. 2005. Explaining de facto judicial independence. PhilippsUniversität Marburg, Working Paper No. 200507. Hoff, Karla, and Joseph Stiglitz. 2004. After The Big Bang? Obstacles to the Emergence of Rule of Law in Post-Communist Societies. American Economic Review 94:753-63. Joireman, Sandra F. 2001. Inherited Legal Systems and Effective Rule of Law: Africa and the Colonial Legacy. Journal of Modern African Studies.39:571-96. Joireman, Sandra F. 2004. Colonization and the Rule of Law: Comparing the Effectiveness of Common Law and Civil Law Countries. Constitutional Political Economy 15:315-38. La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert Vishny. 1999. The Quality of Government. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 15:222-79. Lauth, Hans-Joachim. 2001. Rechtsstaat, Rechtssysteme und Demokratie. In Rechtsstaat und Demokratie, ed. Michael Becker, Hans-Joachim Lauth, and Gert Pickel. Opladen: Leske + Budrich. Lauth, Hans-Joachim. 2004. Demokratie und Demokratiemessung: Eine konzeptionelle Grundlegung für den interkulturellen Vergleich. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. Munck, Gerardo, and Jay Verkuilen. 2002. Conceptualizing and Measuring Democracy: Evaluating Alternative Indices. Comparative Political Studies 35:5-34. Raz, Joseph. 1977. The Rule of Law and Its Virtue. Law Quarterly Review 93:185-211. 18 Rigobon, Roberto, and Dani Rodrick. 2005. Rule of Law, Democracy, Openness, and Income. The Economics of Transitions 13:533-64. Ríos-Figueroa, Julio, and Jeffrey K. Staton. 2008. Unpacking the Rule of Law: A Review of Judicial Independence Measures. IPSA Committee on Concepts and Methods Working Paper Series (Political Concepts No. 21). Sandholtz, Wayne, and Rein Taagepera. 2005. Corruption, Culture, and Communism. International Review of Sociology 15:109-31. Sartori, Giovanni. 1970. Concept Misformation in Comparative Politics. American Political Science Review 64:1033-53. Waldron, Jeremy. 2002. Is the Rule of Law an Essentially Contested Concept (in Florida). Law & Philosophy 21:137-64. Weingast, Barry R. 1997. The Political Foundations of Democracy and the Rule of Law. American Political Science Review 91: 245-63. 19 Table 1 Generator, Dataset, and Scope of the Rule of Law Measures Countries17 Generator Dataset Index Years 2003, 2005, 2007 Bertelsmann Foundation Bertelsmann Transformation Index Rule of Law (BF) 125 Freedom House Freedom in the World Rule of Law (FW) 193 2005-2007 Freedom House Countries at the Crossroads Rule of Law (CC) 30(60) 2003-2006 Freedom House Nations in Transit Judicial Framework and Independence (NT) 29 1996-2007 Global Integrity Global Integrity Index Rule of Law and Access to Justice (GI) 55 2003, 2006, 2007 The PRS Group International Country Risk Guide Law and Order (PRS) 139 1984-2007 World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators Rule of Law (WB) 212 1996, 1998, 2000, 20022007 20 Table 2 Principles of the Rule of Law 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. General laws and not ad personam Publicly promulgated laws Prohibition against retrospective laws Clear and comprehensive laws No contradictory or inconsistent laws No law should be impossible to respect Relative stability in the lawmaking Proportionality in the law Equality before the law Precedence of law, no one is above the law Independent and effective juridical control Due process Liability to pay compensation for any damage caused Absence of arbitrary state action and promotion of legality 21 Table 3 Sources and Coders Measure Sources Coders Rule of Law (BF) Broad range of information Expert. Review by expert from country/region, regional coordinator, and academic board Rule of Law (FW) Broad range of information, including information from news reports, academic analyses, organizations, professionals contacts, and visits (general list of reports used for the survey) Researcher/outside consultant. Review by analysts and academics with regional expertise Rule of Law (CC) Broad range of information (references in narrative report) Scholar/analyst. Review by regional expert committee and internal Freedom House committee Judicial Framework and Independence (NT) Broad range of information (references in narrative report) Expert. Review by academic advisors and Freedom House Rule of Law and Access to Justice (GI) Broad range of information (precise references in report) In country reporters/researchers. Review by Global Integrity Law and Order (PRS) Broad range of information PRS staff with special country expertise Rule of Law (WB) Second-hand scores from eleven representative and thirteen non-representative sources (no basic coding) 22 Table 4 Correlations between the Rule of Law Indices Rule of Law (BF) Rule of Law (FW) Rule of Law (CC) Judicial Framework and Independence (NT) Rule of Law and Access to Justice (GI) Law and Order (PRS) Rule of Law (WB) Rule of Law (BF) 1.00 (359) 0.93 (244) Rule of Law (FW) 0.93 (244) 1.00 (578) 0.45 (56) 0.71 (60) -0.92 (81) -0.95 (83) 0.24 (58) 0.45 (89) 0.19 (303) 0.52 (416) 0.68 (359) 0.80 (577) Rule of Law (CC) 0.45 (56) 0.71 (60) 1.00 (120) -0.86 (17) 0.06 (14) -0.22 (94) 0.31 (120) Judicial Framework and Independence (NT) -0.92 (81) -0.95 (83) -0.86 (17) 1.00 (331) -0.47 (25) -0.36 (210) -0.92 (248) Rule of Law and Access to Justice (GI) 0.24 (58) 0.45 (89) 0.06 (14) -0.47 (25) 1.00 (114) 0.29 (100) 0.60 (114) Law and Order (PRS) 0.19 (303) 0.52 (416) -0.22 (94) -0.36 (210) 0.29 (100) 1.00 (3167) 0.78 (1240) Rule of Law (WB) 0.68 (359) 0.80 (577) 0.31 (120) -0.92 (248) 0.60 (114) 0.78 (1240) 1.00 (1800) Factor loadings (factor 1) 0.99 0.98 - - - -0.10 0.55 Factor loadings (factor 2) -0.04 -0.04 1.00 0.60 Note: Results refer to bivariate Pearson’s r correlations (n in parentheses) and a principal component factor analysis using Oblique rotation. 23 Table 5 Mean Comparisons – Common Law vs. Civil Law PRS 2005 (all) N 138 (civil law) 72 (common law) 98 (civil law) 41 (common law) Mean Rank 96.11 123.49 70.44 68.94 Sum of Ranks 13263.5 8891.5 6903.5 2826.5 Mann-Whitney U Asymp. Sig. 3672.5 0.002** 1965.5 0.839 FW2005 (all) 128 (civil law) 64 (common law 91.18 107.14 11671.0 6857.0 3415.0 0.060* BTI2005 (all) 91 (civil law) 28 (common law) 58.91 63.55 5360.5 1779.5 1174.5 0.533 WB2005 (col.) 118 (civil law) 67 (common law) 80.03 115.84 9443.5 7761.5 2422.5 0.000** PRS 2005 (col.) 81 (civil law) 37 (common law) 57.80 63.22 4682.0 2339.0 1361.0 0.420 FW2005 (col.) 108 (civil law) 59 (common law) 75.05 100.38 8105.5 5922.5 2219.5 0.001** 86 (civil law) 24 (common law) Note: *p<0.1, **p<0.01 (two-tailed). 53.98 60.96 4642.0 1463.0 901.0 0.343 WB2005 (all) BTI2005 (col.) 24 Table 6 Summary of Regression Results with Rule of Law Indices as Dependent Variable WB05 PRS05 FW05 BTI05 Oil Production - (-) - (-) - (-) - (-) Wealth + (+) + (+) + (+) + (+) Country Size - (-) ns (ns) - (ns) ns (ns) Ethno-religious Fractionalization ns (ns) ns (ns) ns (ns) ns (ns) Not Colonized + (ns) + (+) ns (-) - (-) Common Law ns (ns) ns (ns) ns (ns) ns (ns) Communist Past - (ns) + (+) - (ns) ns (ns) Muslim ns (ns) + (+) - (-) - (-) Protestant + (ns) + (ns) + (+) ns (+) Note: + denotes a positive, significant association; - denotes a negative, significant association; ns denotes an insignificant association (p>0.1); bracketed results refer to the analysis with restricted (i.e., common) country coverage. 25 Notes 1 All descriptive information on the datasets is found on the webpages of the providers if no other source or reference is mentioned. 2 http://www.bertelsmann-transformation-index.de 3 http://www.freedomhouse.org 4 This organization has faced serious critique; it has been accused of having a right-wing bias and to overstate the level of freedom in ‘US-friendly’ countries (Bollen 1992, 205; Chomsky and Herman 1988). 5 http://www.globalintegrity.org 6 http://www.prsgroup.com 7 http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi2007 8 This impression is supported by the results (not reported) of a simple statistical test showing that, on average, the countries included in the sample are significantly larger (measured by area) and richer (measured by GDP/capita) than the ones excluded. 9 This critique also applies to the third Freedom House measure, since CC, among others, builds upon the attributes effective and democratic control of the police, military, and security service and that police, military, and security services refrain from interference in politics. 10 PRS is also characterized by the opposite pitfall, namely excessive minimalism, as popular observance of the law is not enough to secure order (the state and foreign powers could also ruin it). PRS is generally defined in unspecific and vague terms, which make it difficult to get a grip on its intension. On the other hand, the simplicity of this measure minimizes the risks of conceptual conflation and redundancy. 11 Similarly, if there is adequate enforcement of property rights and contracts, protection from arbitrary/unjust deprivation of property is in place, and if an independent, impartial, and non-discriminating administration of justice exists, judges/magistrates do not experience interference by executive and legislative. 12 This point also applies to GI. 13 This simple measure has several more sophisticated alternatives, such as Cohen’s kappa and Krippendorf’s alpha. 14 WB constitutes an exception to the latter point, as it is based on the use of an unobserved components model on the data from different sources (including the scores of the other measures examined in this article). The values of WB are weighted averages of the underlying data, with weights reflecting the precision of the individual data sources. 26 15 No aggregation rule is applied in the construction of the Bertelsmann rule of law scale for 2003, as the cases are not coded at a disaggregate level. 16 The few missing values have been replaced by scores based on information from CIA’s The World Fact Book, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook. 17 The number of countries concerns the latest year covered. Most datasets have increased the number of countries covered during their lifetime. 27

![[#EXASOL-1429] Possible error when inserting data into large tables](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/005854961_1-9d34d5b0b79b862c601023238967ddff-300x300.png)