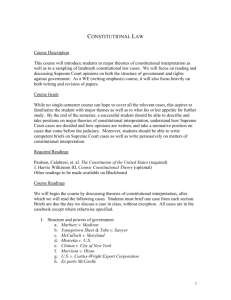

Vlad Perju

advertisement