Lecture 17--Africa 1000-1800 AD

advertisement

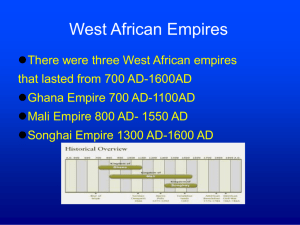

Lecture 17 --Africa 1000-1800 AD North Africa and Egypt: In this period, powerful dynasties arose in Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt. In Tunisia, the Fatmids ruled 909-969 AD, then conquered Egypt and ruled from Egypt 969-1171 AD, before Saladin conquered them. Saladin and Nur-a-din's dynasty, the Ayyubids (1171-1250) ruled Egypt until the uprising of the Mamluks (12501517 AD). Two dynasties ruled Morocco and Spain for a time: the Almoravids (10561147 in Senegal and the Western Sudan, 1062-1118 in Marrakesh and northwestern Africa, and 1085-1147 in Spain) and the Almohads (1130-1269 in northwestern Africa and 1145-1212 in Spain). The Ottomans gradually conquered almost all of the Mediterranean coast of Africa in the 16th century, though their hold was never very tight. By 1800, the principalities of the Mediterranean coast were largely independent and heavily engaged in piracy against Europe, though this would soon end. Even Egypt was mostly independent in practice. The Spread of Islam South of the Sahara: By 1800, Islam heavily influenced the Sudanic belt and the coast of East Africa as far south as modern Zimbabwe. Islam usually mainly converted rulers and merchants, though it brought a literate culture with it. In East Africa, Islamic city states stretched along the coast, trading with points east. In the west, Islam was carried into the sudan by overland routes. Some native rulers, such as the Almoravids and Almohads converted. Sahelian Empires of the Western and Central Sudan: Four states in this area arose into empires between 1000 and 1600 AD: Ghana, Mali, Songhai, and Kanem-Bornu in the central Sudan. Ghana (750-1076, 1087-1180 AD): Ghana was located between the Senegal and Niger Rivers, north of modern Ghana (in what is now southeastern Mauritania, Western Mali, and Eastern Senegal). Its capital, Kumbi Saleh, stood on the border between Sahel and Sahara trade networks. The capital was actually two cities six miles apart separated by a six-mile road. But settlements between the cities became so dense due to the influx of people coming to trade, that it merged into one. Most of the houses were built of wood and clay, but wealthy and important residents lived in homes of wood and stone. This large metropolis of over 30,000 people remained divided after its merger forming two distinct areas within the city—the royal quarter and the merchant quarter. Ghanaian rulers were matrilineal (traced descent through mothers). Various dependent states paid tribute in addition to the nation's trade taxes, making the kings very wealthy. The state controlled the gold trade from the interior northwards, as well as exporting kola nuts and importing salt, cloth, and metal goods. Moslems strongly influenced trade and the state, though they did not rule it. A huge well-armed army secured royal power. Conquered by the Almoravids for eleven years(10761087), they regained their independence, only to be destroyed by the rabidly antiMuslim Sosso people of the Kaniaga kingdom. Mali (1235 to 1645 AD): The Almoravids converted many in the Western Sahel in the 11th century. However, the collapse of Almoravid power in this area left a welter of small states for a time. In the mid-thirteenth century, one of the Ghana successor states, Mali, forged an empire under the leadership of the Keita ruling clan (especially Keita King Sundinaji (1230-1255 AD)). Mali stretched from the Atlantic coast (between the Senegal and Gambia rivers) to half-way along the Niger in the east, holding all of old Ghana and more besides. At its height, it was home to 20 million people. They now controlled the gold trading routes, exporting gold and importing salt and copper. They used war captives in the Niger river valley to grow lots of food. Rice, millet, beans, and yams were grown in large quantities. Metalworking and cotton weaving were the national craft specialties. The Malinke, speakers of Mande, were the main nation, living in cities of 10-15,000 surrounded by farmland. The Keita kings were moslems, who made the required pilgrimage to Mecca, especially in the 13th-14th century. Niani was the capital, located on a tributary of the Niger in the savannah on the edge of the forest, close to sources of gold, kola nuts, and palm oil. Mali was less a centralized bureaucracy and more the center of a vast sphere of influence which contained both subject kingdoms and centrally ruled provinces. The ruler was known as the Mansa, or "emperor". The greatest ruler was Mansa Musa (131237), whose pilgrimage to Mecca involved spending so much money, it triggered inflation all along his route. Musa was so generous that he ran out of money and had to take out a loan to be able to afford the journey home. Under his rule, the city of Timbuktu became known for its madrasas (Muslim religious schools), libraries, poets, and architects—a center for culture. The Mali Empire maintained a professional, full-time army in order to defend its borders. The entire nation was mobilized with each tribe obligated to provide a quota of fighting age men. The military was 90% footmen and 10% cavalry. An infantryman, regardless of weapon (bow, spear, etc.) was called a sofa. Sofas were organized into tribal units under the authority of an officer called the kelé-kun-tigui or "war-tribemaster". The common sofa was armed with a large shield constructed out of wood or animal hide and a stabbing spear called a tamba. Bowmen formed a large portion of the sofas. Three bowmen supporting one spearman was the ratio in Kaabu and the Gambia by the mid 16th century. Equipped with two quivers and a shield, Mandinka bowmen used iron headed arrows with barbed tipped that were usually poisoned. They also used flaming arrows for siege warfare. Cavalry wore chainmail and fought with spears and lances. In the 15th century, strife over the throne eroded Mali's power and the rival state of Songhai arose. Songhai (1275-1591 AD): Songhai became a major power as Mali declined, in the reign of Sonni Ali (1464-1492), becoming the strongest state in Africa. The Songhai are thought to have settled at Gao as early as 800 A.D., but did not establish it as the capital until the 11th Century, during the reign of Dia Kossoi. However, the Dia dynasty soon gave way to the Sonni, preceding the ascension of Sulaiman-Mar, who gained independence and hegemony over the city and was a forbearer of Sonni Ali Ber. Mar is often credited with wresting power away from the Mali Empire and gaining independence for the then small Songhai kingdom. Sonni Ali overran most of the old Mali empire and regions east of it, especially dominating the Niger valley. They now controlled the trade routes northwards. Sonni Ali was a Moslem and he promoted moslem governance and scholarship. Timbuktu became the premiere center of learning for the entire Sudan. In its last years, however, civil war tore the state apart. Kanem and Kanem-Bornu(1000-1396 AD, 1396-1575 AD, 1575-1893 AD ): Kanem arose after 1100 AD in the central Sudan around Lake Chad as a confederation of black nomadic tribes. King Mai Dunama Dibbalemi (1221-1259 AD) and his nobles embraced Islam and used it to sanction his rule and to justify expansion through wars against polytheists. Civil war and invasion shifted the Kingdom's main focus southwest to the Bornu region. Turkish aid ad guns enabled the Kanuri leader Idris Alawma (1575-1610 AD) to unite Kanem and Bornu into a moslem state, extending his rule even into Hausaland. By 1700, his empire was crumbling, though the state lingered on until 1893 in weakened form. The Eastern Sudan: Christian states survived along the upper Nile from the 7th to the 13th century AD. However, Islam gradually spread into the area, replacing Christianity, which was strongest among the elites. By the 18th century, Moslems ruled the whole area. The Forestlands—Coastal West and Central Africa West African Forest Kingdoms: The Example of Benin: The Benin Empire or Edo Empire (1440-1897) was a large pre-colonial African state of modern Nigeria. It was a sophisticated state. The city of Ibinu (later called Benin City) was founded in 1180 AD on the African coast; it became a city-state, and after 1440, the capital of an Empire. Benin State and Society: In its early years, the power of the king (oba) was limited by an order of tribal chieftans(the uzama). Only in the fifteenth century, with King Euware, did the monarchy establish autocratic power and begin enlarging the state. Oba Ewuare the Great (1440-1475 AD), the first Golden Age Oba, is credited with turning Benin City into a military fortress protected by moats and walls. It was from this bastion that he launched his military campaigns and began the expansion of the kingdom from the Edo-speaking heartlands. The lands of Idah, Owo, Akure all came under the central authority of the Edo Empire. At its maximum extent the empire is claimed by the Edos to have extended from Onitsha in the east, through the forested southwestern region of Nigeria and into the present-day nation of Ghana. The Obas governed along with a council of townsfolk and chieftans, though over time, the council grew weaker. By the 17th century, the Oba was seen as a supernatural figure. Humans were sacrificed in the worship of former kings. Benin Art: The Benin were master artists, especially in brass sculptures, though they also worked in terracotta and ivory. The best work are bronze plagues showing legendary and historical scenes, once mounted on the walls and columns of the royal palace. They also liked making brass heads. These artifacts show the sophistication of some African societies before major European contact. European Arrivals on the Coastlands: Between 1400 and 1800, trade with Europeans began working changes on the western coast of Africa. Europeans came to buy slaves, gold, and ivory and brought European manufactured goods and American foodstuffs to Africa. Corn, peanuts, squash, sweet potatos, manioc and cocoa spread across western and central Africa. Coastal states grew in power off the trade, but also began to attack their neighbors to obtain more slaves to sell to the Europeans. Europeans dubbed regions of the coast according to the products they bought there—Grain/Pepper coast, Ivory Coast, Gold Coast, Slave Coast, etc. Senegambia: The region between the Senegal and Gambia rivers was one of the first to be affected. Senegambians provided gold, salt, cotton goods, hides, and copper as well as 1/3rd of all slaves sold to Europeans in the 16th century. After that, the slave trade shifted south and east. The Gold Coast: After 1500, it was the major outlet for West African gold trading. Beginning with the Portuguese in Elmina in 1481, European nations began building coastal trading posts/forts. The trade encouraged the growth of larger states. American crops spread here, helping prosperity, but rising levels of slave trading disrupted the gold trade. Central Africa: Before 1500, formidable natural barriers kept most outsiders out of Central Africa: swamps, rainforest, and desert. After 1500, the Portuguese traded first for ivory and cotton cloth, then increasingly for slaves. The Kongo Kingdom: The Kingdom of Kongo (c. 1400 – 1914) (Kongo: Kongo dya Ntotila or Wene wa Kongo) was an African kingdom located in west central Africa in what are now northern Angola, Cabinda, Republic of the Congo, and the western portion of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. At its greatest extent, it reached from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Kwango River in the east, and from the Congo River in the north to the Kwanza River in the south. It was as large as England. The kingdom consisted of several core provinces ruled by a monarch, the Manikongo (sixteenth century spelling of 'Mwene Kongo) of the Bakongo (Kongo peoples, also known as the Essikongo), but its sphere of influence extended to the neighboring states such as Ngoyo, Kakongo, Ndongo and Matamba as well. It was located on a fertile, well-watered plateau south of the lower Zaire river valley. Kongo society was dominated by its king, who acted as spokesman of the gods, who stood atop a pyramid of tax-collecting governors and village headmen rewarded for their faithfulness in paying their taxes. The Portuguese traded luxury goods, especially textiles, tobacco, and alcohol, for slaves, which depleted the Kingdom's labor supply. The Portuguese initially tried to convert the Africans, but over time, they abandoned that in favor of ever more slave purchasing. Wars increasingly erupted to gain slaves. King Affonso I (1506-1543) was a Christian but fell out with the Portuguese, who tried to undercut his authority. A power struggle now broke out between the Portuguese and the Kongo monarchy, and eventually the ruling class became westernized and the Kongo military came to depend on forces of musketeers. The kings took on Spanish and Portuguese names and sparred constantly with the Portuguese over terms of trade and political power. The Kingdom was Christianized, but developed its own forms of Christianity. In the eighteenth and nineteenth century, Kongo artists began making crucifixes and other religious objects that depicted Jesus as an African. Such objects produced by many workshops over a long period (given their variety) reflect that emerging belief that Kongo was a central part of the Christian world, and fundamental to its history. Angola: Further south, Angola was reduced to chaos by the wars of the Slave Trade. East Africa: Swahili Culture and Commerce: By the 13th century, Islamic traders dominated the eastern coast of Africa from Mogadishu to Kilwa. A common language developed from the interaction of Bantu and Arabic speakers: Swahili. It is the most widely spoken language of sub-Saharan Africa. Although only 5-10 million people speak it as their native language today, Swahili is somewhat of a Southeast African lingua franca, being spoken by around 80 million speakers in the present. Islam and Swahili arose together in the coastal cities. Swahili civilization hit its peak in the 14th-15th centuries. The harbor trading towns were the administrative centers of the local Swahili states, and most were located on coastal islands or peninsulas. The towns were well built and sophisticated in culture. The ruling dynasties were African with some Arab or Persian blood. Society consisted of three groups: local nobility, commoners, and foreign traders, with slaves as a fourth. The export of ivory, gold, slaves, turtle shells, ambergris, leopartd skins, pearls, fish, sandalwood, ebony and local cotton cloth paid for the import of cloth, porcelain, glassware, china, glass beads, and glazed pottery. Cowrie shells were a common currency for the Inland trade, but coins were used in the cities and for foreign trade. The Portuguese and the Osmanis of Zanzibar: The arrival of the Portguese, sworn enemy of the 'Moors' (African Moslems) brought about the collapse of the coastal trade. They saw themselves on a holy crusade and conquered much of the coast for a time. However, after 1660, the Arabian state of Oman drove the Portuguese out of the towns north of Mozambique and established a major base in the Zanzibar archipelago, off the coast of modern Tanzania. By the late 18th century, prosperity returned to the area, until the British took over in the 19th century. Southern Africa: Southeastern Africa: "Great Zimbabwe": The Mutapa Empire, also known as Mwene Mutapa (Portuguese: Monomotapa) or the Empire of Great Zimbabwe was a medieval kingdom (c. 1450-1629) which used to stretch between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers of Southern Africa in the modern states of Zimbabwe and Mozambique. We know it only through the archaelogical remains left behind. It enjoys great fame for the ruins at its old capital of Great Zimbabwe. Great Zimbabwe was a huge 60 acre site encompassing two major building complexes—one is an acropolis, while the other, larger one is was ringed by a 32 foot high, 17 foot thick wall. The acropolis housed a shrine, the large one the royal dwellings. The empire is thought to have been established by the Rozvi whose descendants include the modern-day Shona people. The founder of the ruling dynasty was Mbire, a semi-mythical potentate active in the 14th century. Great Zimbabwe reached its zenith around the 1440s by virtue of its brisk trade in gold conducted with Arabs via the seaport of Sofala south of the Zambezi delta. The fabrics of Gujarat were traded for gold along the coast. By the beginning of the 16th century, the pressures from European and Arab traders began to change the balance of power in the region. Mbire's purported great-great-grandson Nyatsimba was the first ruler to assume the title of the "owner of the Conquered Lands and Peoples", which became hereditary among his descendants. It was he who moved the capital from Great Zimbabwe to Mount Fura by the Zambezi. The Portuguese began their attempts to subdue the Shona state as early as 1505 (when they took hold of Sofala) but were confined to the coast for many years, according to Fernand Braudel until 1613. In the meantime, the Monomotapa Empire was torn apart by rival factions, and the gold from the rivers they controlled was exhausted. The trade in gold was replaced by a trade in slaves. Around this time the Arab states of Zanzibar and Kilwa became prominent powers by providing slaves for Arabia, Persia and India. The empire was further weakened by the Zulus' migration down to their present location in South Africa from an area north of the Zambezi river which they had left because of a plague complicated by a severe drought. It was finally conquered in 1629 by the Portuguese and never recovered. South Africa: The Cape Colony: In 1652, the Dutch created the Cape Colony as a waystation for their ships heading to Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia. It gradually became a farming colony as well, home to the ancestors of the modern Afrikaners. The local Khoikhoi had neither a strong political organization nor an economic base beyond their herds. The Khoikhoi ("men of men") are a historical division of the Khoisan ethnic group of southwestern Africa, closely related to the Bushmen (or San, as the Khoikhoi called them). They had lived in southern Africa since the 5th century AD and, at the time of the arrival of white settlers in 1652, practised extensive pastoral agriculture in the Cape region. They bartered livestock freely to Dutch ships. As Company employees established farms to supply the Cape station, they began to displace the Khoikhoi. Conflicts led to the consolidation of European landholdings and a breakdown of Khoikhoi society. Military success led to even greater Dutch control of the Khoikhoi by the 1670s. The Khoikhoi became the chief source of colonial wage labour. As social structures broke down, some Khoikhoi people settled on farms and became bondsmen or farmworkers; others were incorporated into existing clan and family groups of the Xhosa people. The colony also imported slaves. Slavery set the tone for relations between the emergent and ostensibly "white" Afrikaner population and the "coloreds" of other races. Free or not, the latter were eventually identified with slave peoples. After the first settlers spread out around the Company station, nomadic white livestock farmers, or Trekboers, moved more widely afield, leaving the richer, but limited, farming lands of the coast for the drier interior tableland. There they contested still wider groups of Khoikhoi cattle herders for the best grazing lands. Again the Khoikhoi lost. By 1700, their way of life was destroyed. Cape Society was thus a complex mixture of Dutch officials and ministers, the Trekboers, the Khoikhoi, slaves and the children of interbreeding between the groups. A new vernacular language of the colonials now emerged: Afrikaans, derived from the Dutch language, but influenced by contact with locals. After 1806, the British took over the colony.