Rostovian take

advertisement

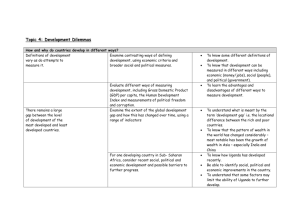

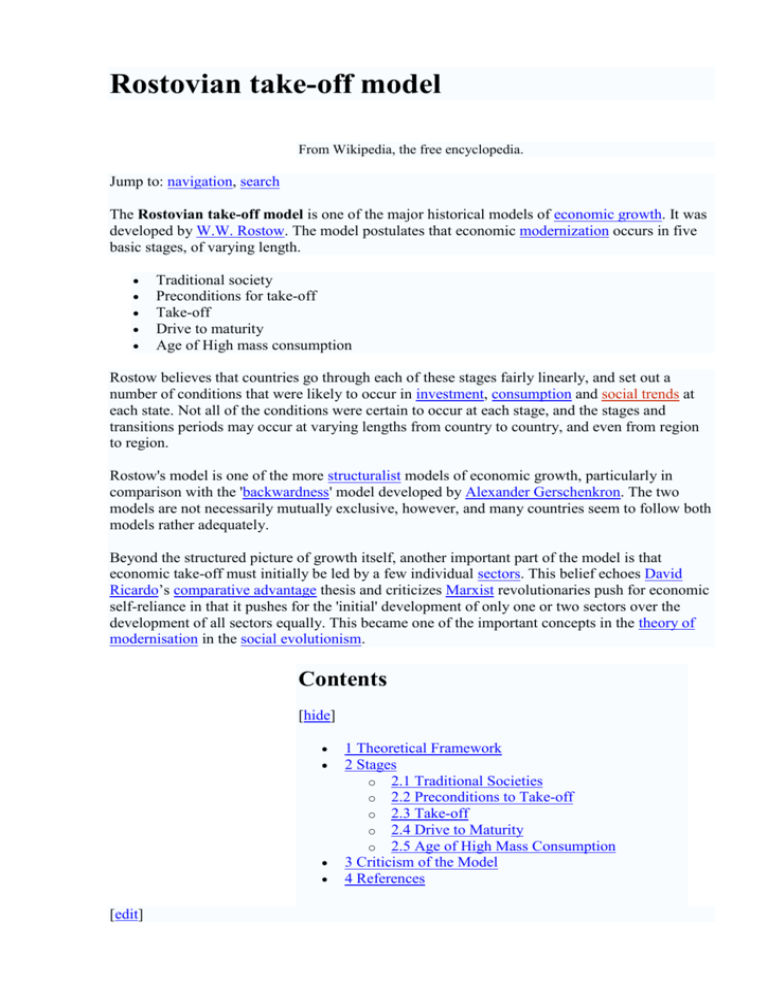

Rostovian take-off model From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Jump to: navigation, search The Rostovian take-off model is one of the major historical models of economic growth. It was developed by W.W. Rostow. The model postulates that economic modernization occurs in five basic stages, of varying length. Traditional society Preconditions for take-off Take-off Drive to maturity Age of High mass consumption Rostow believes that countries go through each of these stages fairly linearly, and set out a number of conditions that were likely to occur in investment, consumption and social trends at each state. Not all of the conditions were certain to occur at each stage, and the stages and transitions periods may occur at varying lengths from country to country, and even from region to region. Rostow's model is one of the more structuralist models of economic growth, particularly in comparison with the 'backwardness' model developed by Alexander Gerschenkron. The two models are not necessarily mutually exclusive, however, and many countries seem to follow both models rather adequately. Beyond the structured picture of growth itself, another important part of the model is that economic take-off must initially be led by a few individual sectors. This belief echoes David Ricardo’s comparative advantage thesis and criticizes Marxist revolutionaries push for economic self-reliance in that it pushes for the 'initial' development of only one or two sectors over the development of all sectors equally. This became one of the important concepts in the theory of modernisation in the social evolutionism. Contents [hide] [edit] 1 Theoretical Framework 2 Stages o 2.1 Traditional Societies o 2.2 Preconditions to Take-off o 2.3 Take-off o 2.4 Drive to Maturity o 2.5 Age of High Mass Consumption 3 Criticism of the Model 4 References Theoretical Framework Rostow's model is descendent from the liberal school of economics, emphasizing the efficacy of modern concepts of free trade and the ideas of Adam Smith. It also denies Friedrich List’s argument that countries reliant on exporting raw materials may get “locked in”, and be unable to diversify, in that Rostow’s model states that countries may need to depend on a few raw material exports to finance the development of manufacturing sectors which are not yet of superior competitiveness in the early stages of take-off. In that way, Rostow’s model does not deny John Maynard Keynes in that it allows for a degree of government control over domestic development not generally accepted by some ardent free trade advocates. Although empirical at times, Rostow is hardly free of normative discourse. As a basic assumption, Rostow believes that countries want to modernize as he describes modernization, and that the society will ascent to the materialistic norms of economic growth. [edit] Stages [edit] Traditional Societies Traditional societies are marked by their pre-Newtonian understanding and use of technology. These are societies which have pre-scientific understandings of gadgets, and believe that gods or spirits facilitate the procurement of goods, rather than man and his own ingenuity. The norms of economic growth are completely absent from these societies. [edit] Preconditions to Take-off The preconditions to take-off are, to Rostow, that the society begins committing itself to secular education, that it enables a degree of capital mobilization, especially through the establishment of banks and currency, that an entrepreneurial class form, and that the secular concept of manufacturing develops, with only a few sectors developing at this point. This leads to a take off in ten to fifty years. [edit] Take-off Take-off then occurs when sector led growth becomes common and society is driven more by economic processes than traditions. At this point, the norms of economic growth are well established. In discussing the take-off, Rostow's is a noted early adopter of the term “transition”, which is to describe the passage of a traditional to a modern economy. After take-off, a country will take as long as fifty to one hundred years to reach maturity. [edit] Drive to Maturity The drive to maturity refers to the need for the economy itself to diversify. The sectors of the economy which lead initially begin to level off, while other sectors begin to take off. This diversity leads to greatly reduced rates of poverty and rising standards of living, as the society no longer needs to sacrifice its comfort in order to strengthen certain sectors. [edit] Age of High Mass Consumption The age of high mass consumption refers to the period of contemporary comfort afforded many western nations, wherein consumers concentrate on durable goods, and hardly remember the subsistence concerns of previous stages. Rostow uses the Buddenbrooks dynamics metaphor to describe this change in attitude. In Thomas Mann’s novel, Buddenbrooks, a family is chronicled for three generations. The first generation is interested in economic development, the second in its position in society. The third, already having money and prestige, concerns itself with the arts and music, worrying little about those previous, earthly concerns. So too, in the age of high mass consumption, a society is able to choose between concentrating on military and security issues, on equality and welfare issues, or on developing great luxuries for its upper class. Each country in this position chooses its own balance between these three goals. [edit] Criticism of the Model Rostow's thesis assumes a strong bias towards a western model of modernization. It deemphasizes any difference between how leading sectors develop in free and controlled markets. However, Rostow’s consideration of non-western cases such as China shows that to some extent, modernization can be achieved in different ways and through free market or controlled economic means and still fit into his model. It is more at his description of the final age, the age of high mass consumption, where controlled economies seem most to find no niche in Rostow’s work. Even there, though, it could be said that the society seeks out economic equality at the complete detriment of any luxury. The most disabling assumption that Rostow is accused of is trying to fit economic progress into a linear system. This charge is correct in that many countries make false starts, reach a degree of transition and then slip back, or as is the case in contemporary Russia, slip back from high mass consumption (or almost) to a country in transition. On the other hand, Rostow’s analysis seems to emphasize success because it is trying to explain success. To Rostow, if a country can be a disciplined, uncorrupt investor in itself, can establish certain norms into its society and polity, and can identify sectors where it has some sort of advantage, it can enter into transition and eventually reach modernity. Rostow would point to a failure in one of these conditions as a cause for non-linearity. Another problem that Rostow’s work has is that it considers mostly large countries: countries with a large population (Japan), with natural resources available at just the right time in its history (Coal in Northern European countries), or with a large land mass (Argentina). He has little to say and indeed offers little hope for small countries, such as Rwanda, which do not have such advantages. In my opinion, this lack cuts to the heart of his analysis. Neo-liberal economic theory to Rostow, and many others, does offer hope to much of the world that economic maturity is coming and the age of high mass consumption is high. But that does leave a sort of 'grim meathook future'[1] for the outliers, which do not have the resources, political will, or external backing to become competitive. (See Dependency theory) [edit] References 1. ^ "Grim Meathook Future" is a quote from new media writer Joshua Ellis [2]. W. W. Rostow. The Stages of Economic Growth: A non-communist manifesto Cambridge University Press (1960) Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rostovian_take-off_model" Dependency theory From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Jump to: navigation, search International Relations Theory Realism Liberalism Idealism Neoconservatism Institutionalism Functionalism Marxism Critical theory Isolationism Dependency theory is the body of social science theories by various intellectuals, both from the Third World and the First World, that create a worldview which suggests that the wealthy nations of the world need a peripheral group of poorer states in order to remain wealthy. Dependency theory states that the poverty of the countries in the periphery is not because they are not integrated into the world system, or not 'fully' integrated as is often argued by free market economists, but because of how they are integrated into the system. The premises of dependency theory are: Poor nations provide natural resources, cheap labor, a destination for obsolete technology, and markets to the wealthy nations, without which they could not have the standard of living they enjoy. First World nations actively, but not necessarily consciously, perpetuate a state of dependency through various policies and initiatives. This state of dependency is multifaceted, involving economics, media control, politics, banking and finance, education, sport and all aspects of human resource development. Any attempt by the dependent nations to resist the influences of dependency will result in economic sanctions and/or military invasion and control. This is very rare, however, and dependency is enforced far more by the wealthy nations setting the rules of international trade and commerce. Dependency theory first emerged in the 1950s, advocated by Raul Prebisch whose research found that the wealth of poor nations tended to decrease when the wealth of rich nations increased. The theory quickly divided into diverse schools. Some, most notably Andre Gunder Frank, adapted it to Marxism. "Standard" dependency theory differs sharply from Marxism, however, arguing against internationalism and any hope of progress in less developed nations towards industrialization and a liberating revolution. Former Brazilian President Fernando Henrique Cardoso wrote extensively on dependency theory while in political exile. The American sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein refined the Marxist aspect of the theory, and called it the "world system." Contents [hide] 1 Spread of theory 2 Implications 3 Practical Failure 4 See also 5 External link [edit] Spread of theory Dependency theory became popular in the 1960s and 1970s as a criticism of standard development theory that seemed to be failing due to the continued widespread poverty of large parts of the world. With the seeming growth of the East Asian economies and India in the last few years, however, the theory has fallen somewhat out of favour. It disagrees sharply with classical and free-market economics. It is far more accepted in other disciplines such as history and anthropology, which can count for or against it. The system of dependency was said to be created with the industrial revolution and the expansion of European empires around the world due to their superior power and wealth. Some argue that before this expansion, the exploitation was internal, with the major economic centres dominating the rest of the country (for example southeast England dominating the British Isles, or the Northeast United States dominating the south and east). Establishing global trade patterns in the nineteenth century allowed this system to spread to a global level. That had the benefit of further isolating the wealthy from both the dangers of peasant revolts and rebellions by the poor. Rather than turn on their oppressors as in the American Civil War or in communist revolutions, the poor could no longer reach the wealthy and thus the less developed nations became engulfed in regular civil wars. Once the superiority of rich nations was established, it could not be shaken off. This control ensures that all profits in less developed countries are taken by the better developed nations, preventing reinvestment and thus growth. [edit] Implications While there are many different and conflicting ideas on how developing countries can avoid the negative consequences of such a world system, several of the following practices were adopted at one time or another by such countries: Promotion of domestic industry. By subsidizing and protecting industries within the periphery nation, these third-world countries can produce their own products rather than simply export raw materials. Import limitations. By limiting the importation of both luxury goods and manufactured goods that can be produced within the country, supposedly, the country can avoid having its capital and resources siphoned off. Forbidding foreign investment. Some governments took steps to keep foreign companies and individuals from owning or operating property that draws on the resources of the country. Nationalization. Some governments have gone so far as to forcibly take over foreign-owned companies on behalf of the state, in order to keep profits within the country. [edit] Practical Failure While dependency theory as a purely theoretical approach to global economics still exists, to date, all attempts to use the theory to find a practical solution within its framework have failed. The reasons include, but are not limited to: Corruption. State-owned industries tend to have a much higher rate of corruption than privatelyowned companies. Lack of competition. By subsidizing in-country industries and preventing outside imports, these companies have no incentive to improve their products, to try and become more efficient in their processes, to please customers, or to research new innovations. Proponents of dependency theory claim that the theory of comparative advantage breaks down when capital - including both physical capital like machines and financial capital - is highly mobile as it is under the conditions of globalization. For this reason, the theories of dependency theory may offer many new insights in a world of highly mobile multinational corporations. Market economists have any variety of case studies to point to in order to discredit dependency theory; the improvement of India's economy after it moved from state-controlled business to open trade is by far one of the most cited examples (see also economy of India, Commanding Heights). Also, India's example seemingly contradicts dependency theorists' aforementioned claims about comparative advantage and mobility, as much as its economic growth came as the result of such movements as outsourcing, one of the most mobile forms of capital transfer. [edit] See also [edit] External link Sociocultural evolution An introduction to dependency theory Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dependency_theory" Dependency Theory: An Introduction Vincent Ferraro, Mount Holyoke College South Hadley, MA July 1996 Background Dependency Theory developed in the late 1950s under the guidance of the Director of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America, Raul Prebisch. Prebisch and his colleagues were troubled by the fact that economic growth in the advanced industrialized countries did not necessarily lead to growth in the poorer countries. Indeed, their studies suggested that economic activity in the richer countries often led to serious economic problems in the poorer countries. Such a possibility was not predicted by neoclassical theory, which had assumed that economic growth was beneficial to all (Pareto optimal) even if the benefits were not always equally shared. Prebisch's initial explanation for the phenomenon was very straightforward: poor countries exported primary commodities to the rich countries who then manufactured products out of those commodities and sold them back to the poorer countries. The "Value Added" by manufacturing a usable product always cost more than the primary products used to create those products. Therefore, poorer countries would never be earning enough from their export earnings to pay for their imports. Prebisch's solution was similarly straightforward: poorer countries should embark on programs of import substitution so that they need not purchase the manufactured products from the richer countries. The poorer countries would still sell their primary products on the world market, but their foreign exchange reserves would not be used to purchase their manufactures from abroad. Three issues made this policy difficult to follow. The first is that the internal markets of the poorer countries were not large enough to support the economies of scale used by the richer countries to keep their prices low. The second issue concerned the political will of the poorer countries as to whether a transformation from being primary products producers was possible or desirable. The final issue revolved around the extent to which the poorer countries actually had control of their primary products, particularly in the area of selling those products abroad. These obstacles to the import substitution policy led others to think a little more creatively and historically at the relationship between rich and poor countries. At this point dependency theory was viewed as a possible way of explaining the persistent poverty of the poorer countries. The traditional neoclassical approach said virtually nothing on this question except to assert that the poorer countries were late in coming to solid economic practices and that as soon as they learned the techniques of modern economics, then the poverty would begin to subside. However, Marxists theorists viewed the persistent poverty as a consequence of capitalist exploitation. And a new body of thought, called the world systems approach, argued that the poverty was a direct consequence of the evolution of the international political economy into a fairly rigid division of labor which favored the rich and penalized the poor. How Can One Define Dependency Theory? The debates among the liberal reformers (Prebisch), the Marxists (Andre Gunder Frank), and the world systems theorists (Wallerstein) was vigorous and intellectually quite challenging. There are still points of serious disagreements among the various strains of dependency theorists and it is a mistake to think that there is only one unified theory of dependency. Nonetheless, there are some core propositions which seem to underlie the analyses of most dependency theorists. Dependency can be defined as an explanation of the economic development of a state in terms of the external influences--political, economic, and cultural--on national development policies (Osvaldo Sunkel, "National Development Policy and External Dependence in Latin America," The Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 6, no. 1, October 1969, p. 23). Theotonio Dos Santos emphasizes the historical dimension of the dependency relationships in his definition: [Dependency is]...an historical condition which shapes a certain structure of the world economy such that it favors some countries to the detriment of others and limits the development possibilities of the subordinate economics...a situation in which the economy of a certain group of countries is conditioned by the development and expansion of another economy, to which their own is subjected. (Theotonio Dos Santos, "The Structure of Dependence," in K.T. Fann and Donald C. Hodges, eds., Readings in U.S. Imperialism. Boston: Porter Sargent, 1971, p. 226) There are three common features to these definitions which most dependency theorists share. First, dependency characterizes the international system as comprised of two sets of states, variously described as dominant/dependent, center/periphery or metropolitan/satellite. The dominant states are the advanced industiral nations in the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The dependent states are those states of Latin America, Asia, and Africa which have low per capita GNPs and which rely heavily on the export of a single commodity for foreign exchange earnings. Second, both definitions have in common the assumption that external forces are of singular importance to the economic activities within the dependent states. These external forces include multinational corporations, international commodity markets, foreign assistance, communications, and any other means by which the advanced industrialized countries can represent their economic interests abroad. Third, the definitions of dependency all indicate that the relations between dominant and dependent states are dynamic because the interactions between the two sets of states tend to not only reinforce but also intensify the unequal patterns. Moreover, dependency is a very deepseated historical process, rooted in the internationalization of capitalism. Dependency is an ongoing process: Latin America is today, and has been since the sixteenth century, part of an international system dominated by the now-developed nations.... Latin underdevelopment is the outcome of a particular series of relationships to the international system. Susanne Bodenheimer, "Dependency and Imperialism: The Roots of Latin American Underdevelopment," in Fann and Hodges, Readings, op. cit., p. 157. In short, dependency theory attempts to explain the present underdeveloped state of many nations in the world by examining the patterns of interactions among nations and by arguing that inequality among nations is an intrinsic part of those interactions. The Structural Context of Dependency: Is it Capitalism or is it Power? Most dependency theorists regard international capitalism as the motive force behind dependency relationships. Andre Gunder Frank, one of the earliest dependency theorists, is quite clear on this point: ...historical research demonstrates that contemporary underdevelopment is in large part the historical product of past and continuing eonomic and other relations between the satellite underdeveloped and the now developed metropolitan countries. Furthermore, these relations are an essential part of the capitalist system on a world scale as a whole. Andre Gunder Frank, "The Development of Underdevelopment," in James D. Cockcroft, Andre Gunder Frank, and Dale Johnson, eds., Dependence and Underdevelopment. Garden City, New York: Anchor Books, 1972, p. 3. According to this view, the capitalist system has enforced a rigid international division of labor which is responsible for the underdevelopment of many areas of the world. The dependent states supply cheap minerals, agricultural commodities, and cheap labor, and also serve as the repositories of surplus capital, obsolescent technologies, and manufactured goods. These functions orient the economies of the dependent states toward the outside: money, goods, and services do flow into dependent states, but the allocation of these resources are determined by the economic interests of the dominant states, and not by the economic interests of the dependent state. This division of labor is ultimately the explanation for poverty and there is little question but that capitalism regards the division of labor as a necessary condition for the efficient allocation of resources. The most explicit manifestation of this characteristic is in the doctrine of comparative advantage. Moreover, to a large extent the dependency models rest upon the assumption that economic and political power are heavily concentrated and centralized in the industrialized countries, an assumption shared with Marxist theories of imperialism. If this assumption is valid, then any distinction between economic and political power is spurious: governments will take whatever steps are necessary to protect private economic interests, such as those held by multinational corporations. Not all dependency theorists, however, are Marxist and one should clearly distinguish between dependency and a theory of imperialism. The Marxist theory of imperialism explains dominant state expansion while the dependency theory explains underdevelopment. Stated another way, Marxist theories explain the reasons why imperialism occurs, while dependency theories explain the consequences of imperialism. The difference is significant. In many respects, imperialism is, for a Marxist, part of the process by which the world is transformed and is therefore a process which accelerates the communist revolution. Marx spoke approvingly of British colonialism in India: England has to fulfil a double mission in India: one destructive, the other regenerating--the annihilation of old Asiatic society, and the laying of the material foundations of Western society in Asia. Karl Marx, "The Future Results of the British Rule in India," New York Daily Tribune, No. 3840, August 8, 1853. For the dependency theorists, underdevelopment is a wholly negative condition which offers no possibility of sustained and autonomous economic activity in a dependent state. Additionally, the Marxist theory of imperialism is self-liquidating, while the dependent relationship is self-perpetuating. The end of imperialism in the Leninist framework comes about as the dominant powers go to war over a rapidly shrinking number of exploitable opportunities. World War I was, for Lenin, the classic proof of this proposition. After the war was over, Britain and France took over the former German colonies. A dependency theorist rejects this proposition. A dependent relationship exists irrespective of the specific identity of the dominant state. That the dominant states may fight over the disposition of dependent territories is not in and of itself a pertinent bit of information (except that periods of fighting among dominant states affords opportunities for the dependent states to break their dependent relationships). To a dependency theorist, the central characteristic of the global economy is the persistence of poverty throughout the entire modern period in virtually the same areas of the world, regardless of what state was in control. Finally, there are some dependency theorists who do not identify capitalism as the motor force behind a dependent relationship. The relationship is maintained by a system of power first and it does not seem as if power is only supported by capitalism. For example, the relationship between the former dependent states in the socialist bloc (the Eastern European states and Cuba, for example) closely paralleled the relationships between poor states and the advanced capitalist states. The possibility that dependency is more closely linked to disparities of power rather than to the particular characteristics of a given economic system is intriguing and consistent with the more traditional analyses of international relations, such as realism. The Central Propositions of Dependency Theory There are a number of propositions, all of which are contestable, which form the core of dependency theory. These propositions include: 1. Underdevelopment is a condition fundamentally different from undevelopment. The latter term simply refers to a condition in which resources are not being used. For example, the European colonists viewed the North American continent as an undeveloped area: the land was not actively cultivated on a scale consistent with its potential. Underdevelopment refers to a situation in which resources are being actively used, but used in a way which benefits dominant states and not the poorer states in which the resources are found. 2. The distinction between underdevelopment and undevelopment places the poorer countries of the world is a profoundly different historical context. These countries are not "behind" or "catching up" to the richer countries of the world. They are not poor because they lagged behind the scientific transformations or the Enlightenment values of the European states. They are poor because they were coercively integrated into the European economic system only as producers of raw materials or to serve as repositories of cheap labor, and were denied the opportunity to market their resources in any way that competed with dominant states. 3. Dependency theory suggests that alternative uses of resources are preferable to the resource usage patterns imposed by dominant states. There is no clear definition of what these preferred patterns might be, but some criteria are invoked. For example, one of the dominant state practices most often criticized by dependency theorists is export agriculture. The criticism is that many poor economies experience rather high rates of malnutrition even though they produce great amounts of food for export. Many dependency theorists would argue that those agricultural lands should be used for domestic food production in order to reduce the rates of malnutrition. 4. The preceding proposition can be amplified: dependency theorists rely upon a belief that there exists a clear "national" economic interest which can and should be articulated for each country. In this respect, dependency theory actually shares a similar theoretical concern with realism. What distinguishes the dependency perspective is that its proponents believe that this national interest can only be satisfied by addressing the needs of the poor within a society, rather than through the satisfaction of corporate or governmental needs. Trying to determine what is "best" for the poor is a difficult analytical problem over the long run. Dependency theorists have not yet articulated an operational definition of the national economic interest. 5. The diversion of resources over time (and one must remember that dependent relationships have persisted since the European expansion beginning in the fifteenth century) is maintained not only by the power of dominant states, but also through the power of elites in the dependent states. Dependency theorists argue that these elites maintain a dependent relationship because their own private interests coincide with the interests of the dominant states. These elites are typically trained in the dominant states and share similar values and culture with the elites in dominant states. Thus, in a very real sense, a dependency relationship is a "voluntary" relationship. One need not argue that the elites in a dependent state are consciously betraying the interests of their poor; the elites sincerely believe that the key to economic development lies in following the prescriptions of liberal economic doctrine. The Policy Implications of Dependency Analysis If one accepts the analysis of dependency theory, then the questions of how poor economies develop become quite different from the traditional questions concerning comparative advantage, capital accumulation, and import/export strategies. Some of the most important new issues include: 1. The success of the advanced industrial economies does not serve as a model for the currently developing economies. When economic development became a focused area of study, the analytical strategy (and ideological preference) was quite clear: all nations need to emulate the patterns used by the rich countries. Indeed, in the 1950s and 1960s there was a paradigmatic consensus that growth strategies were universally applicable, a consensus best articulated by Walt Rostow in his book, The Stages of Economic Growth. Dependency theory suggests that the success of the richer countries was a highly contingent and specific episode in global economic history, one dominated by the highly exploitative colonial relationships of the European powers. A repeat of those relationships is not now highly likely for the poor countries of the world. 2. Dependency theory repudiates the central distributive mechanism of the neoclassical model, what is usually called "trickle-down" economics. The neoclassical model of economic growth pays relatively little attention to the question of distribution of wealth. Its primary concern is on efficient production and assumes that the market will allocate the rewards of efficient production in a rational and unbiased manner. This assumption may be valid for a well-integrated, economically fluid economy where people can quickly adjust to economic changes and where consumption patterns are not distorted by non-economic forces such as racial, ethnic, or gender bias. These conditions are not pervasive in the developing economies, and dependency theorists argue that economic activity is not easily disseminated in poor economies. For these structural reasons, dependency theorists argue that the market alone is not a sufficient distributive mechanism. 3. Since the market only rewards productivity, dependency theorists discount aggregate measures of economic growth such as the GDP or trade indices. Dependency theorists do not deny that economic activity occurs within a dependent state. They do make a very important distinction, however, between economic growth and economic development. For example, there is a greater concern within the dependency framework for whether the economic activity is actually benefitting the nation as a whole. Therefore, far greater attention is paid to indices such as life expectancy, literacy, infant mortality, education, and the like. Dependency theorists clearly emphasize social indicators far more than economic indicators. 4. Dependent states, therefore, should attempt to pursue policies of self-reliance. Contrary to the neo-classical models endorsed by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, greater integration into the global economy is not necessarily a good choice for poor countries. Often this policy perspective is viewed as an endorsement of a policy of autarky, and there have been some experiments with such a policy such as China's Great Leap Forward or Tanzania's policy of Ujamaa. The failures of these policies are clear, and the failures suggest that autarky is not a good choice. Rather a policy of self-reliance should be interpreted as endorsing a policy of controlled interactions with the world economy: ppor countries should only endorse interactions on terms that promise to improve the social and economic welfare of the larger citizenry.