Virtuous Teachers and Quality Learning

advertisement

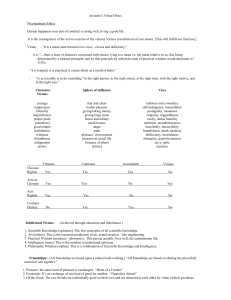

Virtuous Teachers and Quality Learning (Conference Paper, Prague Metropolitan University, 2009) Seán Moran, Waterford Institute of Technology, Ireland Introduction Quality learning is something we desire in all of our institutions. How could it be otherwise? We all want our students to have learning experiences of high quality, experiences which enable them to enrich and develop their knowledge during their time with us. Although we might agree wholeheartedly with this general principle that we ought to promote high quality learning, we would not all subscribe to the same particular view as to exactly what form this ‘high quality learning’ should take however. We teachers are all individuals, and we thus have our own views on what our job involves. Unfortunately, to the bureaucratic mind, this is untidy, inefficient and unacceptable. So we are presented with external targets to hit. Benchmarks, deliverables and success criteria (the labels vary, but the dismal concept remains the same) are defined for us, and our job is to make sure that they are achieved. Our role becomes an instrumental one. We are just the means to the students achieving pre-defined ends efficiently and effectively, whether we - or they - like it or not. Today, I hope to show that there is a better way of conceptualising our role as teachers. I would like to suggest an alternative to modernist obsessions with mechanistic, externallyimposed, short-term ends: to promote a much older, human, internal source of long-term flourishing. In short, I intend to show that 'high quality' flows from virtue. For quality learning, we need virtuous teachers who can also help students to develop their own intellectual virtues. Virtuous teachers When we think of great teachers of the past – Jesus of Nazareth, Socrates of Athens and Comenius of Moravia, for example – we do not evaluate them against how well they achieved some list of targets we have drawn up, but rather by considering their virtues. Chief amongst these was their desire to promote the flourishing of their disciples. They all set about this in different ways: Jesus by telling vivid stories (the Parables); Socrates by asking searching questions (the 'Socratic method') and Comenius by his conversational techniques. Imagine being a student of theirs. Would it ever occur to us to criticise Socrates for not using technology effectively?1 Would we complain about Jesus because his lessons did not equip us with the skill-set needed to compete aggressively in the global economy? And yet, would we deny that we had had a quality learning experience: one which contributed greatly to our overall flourishing? What they, and good teachers of every era, have in common is the virtue of 'practical wisdom' (phronesis in the ancient Greek). Aristotle defined phronesis as 'a true and reasoned state of 1 Even without computers and the internet, he could have done better than scraping wobbly diagrams in the sand with his stick, as Plato describes him doing in the Meno. capacity to act with regard to the things that are good or bad for men’2 In other words, using this virtue will help our students to progress towards the good and away from the bad. When we act from phronesis, we do those things in our classrooms which we hope will promote the flourishing3 of our students. In our situation, this largely means the linguistic flourishing of our students. Of course, merely having these noble aspirations for our students is not enough. We still need to have good academic knowledge (episteme) and imaginative teaching techniques (techne) in order to be able to fulfill our worthy ambitions. The difference is that the teacher's inner virtuous disposition – phronesis – is now seen as the fundamental cause of quality learning, not the existence of external targets. We do our best for our students because that is the kind of people we are. In the real world, of course, these targets are a fact of life and we have to pay some attention to them. This is not a problem for the virtue theory though, for part of phronesis is the sub-virtue of sophrosyne or prudence. It is prudent to have regard to legitimately-constructed targets, syllabuses and learning objectives, to the extent that these can help the students to flourish. But we ought not to follow unquestioningly such prescribed schemes. We cannot use them to evade our ethical duty - our obligation to deploy phronesis to promote students' flourishing - for this would be the teacherly version of the Nuremberg defence (to put things rather too strongly in order to make the point clear). Just as doctors swear a Hippocratic oath to do good for their patients, we too, I suggest, are bound by pedagogical ethics to do good for our students. Externally-imposed orders do not over-ride this obligation. My thesis, then, is that high quality learning is best cultivated by teachers using our virtues to promote the flourishing of students. We do the right thing when we trust our practical wisdom (phronesis), a virtue acquired by years of experience which enables us to recognise the important features of a particular learning situation and to act in such a way as to promote the flourishing of students. We develop an attunement to students and to their learning needs. We deploy whatever techniques and knowledge our practical wisdom tells us will help students - both at that moment and as part of their lifelong learning. And if there is a clash between (i) achieving an immediate target and (ii) the best interests of the students' lifelong flourishing, then we act in a way which favours the latter. For example, there comes a point when good judgement indicates a pause in dealing with phrasal verbs, for a few lighthearted minutes, in order to safeguard the long-term good of the students. If this is not done, and the lesson-plan is rigidly enforced, then the students may well master the phrasal verbs being covered that day but begin to hate the target language. When further language lessons are offered in the future, they might then show an impressive grasp of phrasal verbs by using one ending in “off!” So much for the virtue of phronesis in teachers. But what about our students? Do they also need to bring some virtues to their learning if it is to be a quality experience? My contention is that they do, and that part of our virtuous teaching ought to be directed towards developing our students' intellectual virtues. Virtuous Learners Unlike us teachers, students do not have an obligation to 'act with regard to the things that are good or bad for men' as Aristotle puts it in his definition of phronesis. Of course, we 2 Aristotle Nicomachean Ethics Book VI. For present purposes, we can take 'men' here to mean 'mankind'. 3 Eudaimonia in the Greek. require them not to do any harm to other learners, and we hope that they may even do some good, but this latter hope is not an obligation for students qua learners in the same way that it is an obligation for us qua teachers. Their chief duty as students is to engage in high quality learning. Full engagement is a necessary feature of this quality learning, and this in turn depends on students being well motivated. Good motivations, apart from the fleeting and transitory kind, are based on virtues (unlike bad motivations, which are based on vice). One might object that learning can still occur with very little motivation on the part of the students. And so it can, but only at the expense of their flourishing and only with the exercise of rigorous control by the teacher. Once the control is relaxed, or the student is away from the formal situation, the absence of motivation would make the learning stop immediately. So methods which bypass the need for stable motivations (based in turn on well-entrenched intellectual virtues) are conducive neither to long-term learning nor to flourishing. We can see the importance, then, of helping our students to develop not just their knowledge, but also their intellectual virtues. In fact, some epistemologists argue that knowledge can only be acquired through the operation of these virtues. A true belief only becomes knowledge if the student forms it by the exercise of intellectual virtue. So, if we attempt to teach something to a student without engaging that student's virtues, we will only succeed in programming them, and will not be giving them knowledge. To an extent, this programming is a perfectly acceptable part of teaching - some things just have to be learned 'parrot fashion' – but we need to be aware of the dangers of relying too heavily on behaviourist methods. If we wish to see high quality learning, we must help learners to develop their intellectual virtues. Next, I consider the details of this proposal vis-à-vis the study of languages. Virtues in Language Learning The Irish philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch gives a flavour of what these virtues might be in the case of language learning (paraphrased by Ana Lita, 2003): The study of a language requires patience and humility, the acknowledgement of ignorance (as Socrates considers virtue to require) and, most importantly, an understanding of the “otherness” of a foreign language ... To learn a language means to not only learn its grammar rules and how to apply them, but also to appreciate its individuality, its uniqueness and its independence. This fosters the love that is necessary for deeply understanding a foreign language ... Selfish thoughts and interests must be put aside even when there is a practical value in learning a language. While learning a language for its intrinsic value, the effort displays virtue for it is an example of loving something real outside the self. 4 So what other virtues ought we to help cultivate in students? To answer this, we need to turn to the new philosophical field of virtue epistemology. There are two main schools of thought in contemporary virtue epistemology: those of the Americans Ernest Sosa and Linda Zagzebski. Sosa defines intellectual virtue very broadly to encompass any human attribute which reliably leads to true beliefs. These attributes include not only those features which we would normally consider to be virtues – stable character-traits such as ‘… a disposition to receive others’ say-so when we hear it or read it.’5 but also cognitive qualities such as a 4 Ana Lita “Seeing” Human Goodness: Iris Murdoch On Moral Virtue Minerva - An Internet Journal of Philosophy 7 (2003): 143–172 5 Ernest Sosa (2007) A Virtue Epistemology: Apt Belief and Reflective Knowledge (Oxford: Oxford University Press), p.95 retentive memory and physiological gifts such as acute eyesight. We can see the attraction of a reliable memory as a desirable property of the language student, and a good 'ear' (both physical and metaphorical) as being similarly useful, but whether or not these can be described as 'virtues' is arguable. Zagzebski 6, on the other hand, dismisses such knowledge-conducive properties as good eyesight as mere 'faculties' and argues that genuine intellectual virtue consists of voluntary, stable dispositions to seek what she calls ‘cognitive contact with reality’. In our case of language learning, these would be dispositions to engage with linguistic and cultural realities. Zagzebski gives many examples of intellectual virtues. A selection of these which I feel students need in the lifelong learning of a language are: the social virtues of being communicative, including knowing your audience and how they respond being able to recognize reliable authority autonomy intellectual humility the virtues opposed to ... conformity sensitivity to detail intellectual perseverance, diligence, care and thoroughness originality and creativity the ability to recognize the salient facts insights into persons the ability to think up illuminating ... interpretations of literary texts the virtue that is the mean between the questioning mania and unjustified conviction The need for good judgement This is a very interesting list, with which many of us would agree, but closer analysis reveals that some of the virtues given are in conflict with each other. 'Humility' seems to be opposed to 'autonomy', for example, and likewise 'the virtues opposed to conformity' conflict with that of 'recognising authority'. How are learners to resolve these clashes? Once again, virtue comes to the rescue – in this case the over-riding virtue of phronesis or practical wisdom. Knowing when to be humble and accepting of authority and when to be autonomous and nonconformist is a very important judgement for the learner to make, and this depends on the virtue of practical wisdom. If we teachers always insist on conformity, then the learner never has the opportunities to cultivate the practical wisdom required to make their own judgements. So, as well as structuring our lessons to allow the efficient learning of a language, we also need to allow space for students to develop the intellectual virtues – particularly the virtue of phronesis. We can model virtuous learning and set a good example by, for instance, using a dictionary or other reputable resource ourselves - thus showing that we have the virtue of ‘being able to recognize reliable authority’. Instead of always giving our interpretation of texts in the target language, we can allow the students to try this for themselves first, thus fostering 'the ability to think up illuminating interpretations of literary texts' Yes, it takes longer and is not apparently as efficient, but, in the long run, finding ways such as these of developing not 6 Linda Zagzebski (1996) Virtues of the Mind (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) only language skills and knowledge but also intellectual virtue will reap rewards later on. Conclusions By developing the intellectual virtues in our students (using our own practical wisdom) we will be helping to cultivate lifelong learners who engage in quality learning. If, on the other hand, we do not bear in mind the intellectual virtues and help students to develop them alongside their language proficiency, we will not truly be unleashing the potential of our students. Richard Paul feels that educational institutions do not generally cultivate the virtues, with disastrous consequences: ... the present structure of curricula and teaching not only discourages [the] development [of the intellectual virtues] but also strongly encourages their opposites. Consequently, even the “best” students enter and leave college as largely miseducated persons ... 7 If we want our students to be properly educated and enjoy high quality learning, a consideration of the intellectual virtues is vital. For quality learning, students need virtuous teachers who can help cultivate their intellectual virtues, as well as simply teaching a language and aiming at short-term targets. I leave the last words to a countryman of yours, the Czech educationalist Jan Amos Komensky, better known as Comenius: The virtues are learned by constantly doing what is right…. it is by learning that we find out what we ought to learn, and by acting that we learn to act as we should. … But it is necessary that the child be helped by advice and example at the same time. 8 Biographical Note: After teaching in London, Yorkshire, Cheshire, Manchester and Belfast, and leading the flexible Post Graduate Certificate in Education at The Open University in Ireland, Mgr. Seán Moran now lectures on Masters programmes in education at Waterford Institute of Technology, Ireland and is visiting professor of pedagogy at Zemaitija College, Lithuania. He is also carrying out doctoral research in the philosophy of education at St Patrick’s College, Drumcondra, Dublin.. Email:sean@seanmoran.com 7 Richard Paul, 'Critical Thinking, Moral Integrity and Citizenship: Teaching for the Intellectual Virtues' in Guy Axtell (2000) Knowledge, Belief and Character (Lanham, USA: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.) p.164 8 Comenius, The Great Didactic, London, Adam & Charles Black, 1896, Chap. XXIII, p. 367