The Synodic Period of Jupiter in the Ch'u Silk Manuscript

advertisement

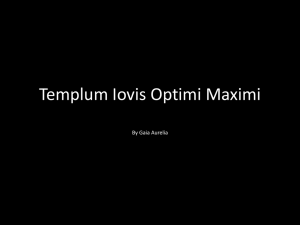

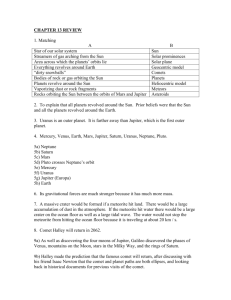

Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) 楚帛書中的歲星會合周期 ——楚帛書歲篇新解 The Synodic Period of Jupiter in the Chu Silk Manuscript ---- A New Interpretation of the Sui Chapter 歷史學系 2000 級 History Department 左婭 Zuo Ya 摘要: 本文首先考察了歲星占中的“贏縮”確鑿的天文學意義——“縮”指的是歲 星的逆行,而“嬴”則選取的是歲星速率較大的時段,從而進一步論證長沙 子彈庫戰國楚帛書中的歲篇是一個圍繞歲星會合周期及周期中的徐疾順逆 展開的有機整體。 Abstract The paper starts from the exploration of the accurate astronomical meanings of Ying 贏 (exceed) and Suo 縮 (recede), both as key descriptions of motions of Jupiter in traditional Chinese astrological literature. Ying 贏 turns out to fall into some accelerating phase of the planet’s prograde motion, and Suo 縮 the retrogression. In light of the conclusion, a further handle of the Sui chapter of Ch’u Silk Manuscript can be possibly achieved, that the whole chapter organically concerned some taboo of synodic cycle of Jupiter. 關鍵詞: 贏縮、會合周期、楚帛書歲篇。 Key words: exceed and recede, the synodic cycle of Jupiter, the Sui Chapter in Ch’u silk manuscript 374 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) Since the Zidanku Chu silk manuscript 子彈庫楚帛書 was excavated in the province of Hunan in the 1940s, a lot of scholars have been drawn to devote their energies continuously into the research of it1. It is known to all that either traditional historical records or archaeological data of Pre-Qin period China is comparatively sparse and fragmentary, especially when part of the textual records had, some to a considerable extent, been elaborated successively as they passed through time and can no longer be regarded comprehensive or free of bias. Dated between the 4th and 3rd century B.C., the Chu silk manuscript undoubtedly appears to be a significant piece of source to shed light on the research of middle and late Warring States period. How manuscript was structured, to be more specific, how the order of reading the paragraphs was arranged remained a problem not yet satisfactorily solved. The solution not only relies on understanding the physical layout of the manuscript as a borrowing from the cosmological theory of Chu people at that time2, but on precisely investigating into the content of each part. Among the three paragraphs our understanding of two have come to mature, one concerning the story telling of the remote history of the world’s creation, the other deploying the taboos of each month in a year. However, the situation is especially difficult for the remaining chapter, for a clear-cut theme, like what manifested in its two counterparts still stays out of our reach. Yet meanwhile researchers have shared one point of view that the chapter concerns some taboo, either of the movements of celestial bodies or of timing. For example, Shang Chengzuo considered the chapter about “the parallel disastrous changes of mountains and rivers caused by the eccentric motions of stars and planets”3. Li Xueqin proposed that the taboo mainly concerns a certain astronomical phenomenon “Ceni” 側匿 and meteors4. Rao Zongyi and Zheng Gang regarded the taboo relative with Jupiter and its abnormal progress “Shici” 失次 (missing the station)6 against the star background5. In Li Ling's view, the chapter pressed on the significance of people's understanding of and deference to time and seasons7. There always exists, it seems, some discrepancies that cannot be reconciled in various explanations. Furthermore, except the structure, the ambiguousness in the study of Sui Chapter also mars the internal evidence to judge the nature of the whole manuscript. In terms of Li Ling’s summary and classification, all the debates about the manuscript’s character fell into three categories, the official monthly almanac (Yueling 月令), the almanac of taboos (Liji 曆忌), and the chapter of celestial governors (Tianguanshu 天 官 書 )8. Each definition manifests some emphasis, differently and partially, on some chapter of the total three. Therefore, the vagueness both inside the Sui chapter and hanging over the manuscript as a whole make further investigations necessary. Before entering the Sui chapter particularly, I would like to call for attention onto two integral characteristics of the manuscript. In the first place, the fine appearance of the manuscript attests to its identity as a piece of work of art. Some researcher of history of art proposed that it is more of a silk painting than a silk manuscript as for all the impressive illustrations around9. And its delicate language and wording, highly 375 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) praised by Shang Chengzuo10, are comparable to the well-known canons like Book of Poetry (Shijing, 詩經), Book of History (Shangshu, 尚書), The Zuo Traditions (Zuozhuan 左傳) and Chu poetry (Chuci, 楚辭). And Rao Zongyi described the fine calligraphy as "clusters of pearls and jade between lines"11. Secondly, whatever interpretation we give to Sui chapter, the fact that all the three paragraphs of the manuscript are loose connected in content can be hardly denied12. The deconcentration of content does apparently go against the integrality of the physical layout. To reconcile the discrepancy, I am inclined to regard the manuscript as a piece of individual writing. All the elements, systematically organized or loose connected, had been derived from the author's academic tradition and his own understanding of the tradition. Three Points Relative to Jupiter in Sui Chapter The observation and record of the synodic cycle of Jupiter, the "exceed and recede" in astrological literature and the incorporation of Jupiter's ephemerides into almanacs are three points worth remarking as we concern the Sui chapter of the manuscript. In accordance with both textual and archaeological data, it is no later than the early Western Han Dynasty that people were able to observe and record the synodic period of Jupiter systematically13. In the Jupiter divination part of the Divination of Five Planets (Wuxingzhan, 五星占), the record of the synodic period is as follows: (The Jupiter) stays visible for 365 days and setting in the West thereafter. It does not rise again in the East until the period of invisibility, thirty days ends. Every 395 days 【Jupiter reappears in the East】. It progresses twenty minutes daily, and one degree every twelve days.14 The whole cycle is divided into two parts by the characteristic phenomena "visibility" and "invisibility", the first lasting 365 days and the latter 30 days. It turns out to be a convenient division bent to adapt to people's common sense of time, that the whole cycle consists a year and a big month (in China's luni-solar calendar). The one-year-pluses-one-month conception of the synodic cycle is more obviously attested by the record of the "rising in the East as a morning star" of Jupiter in the Divination of the Five Planets. The sun shifts its positions with even motion along the zodiac. Meanwhile Jupiter measures out year-by-year the twelve zodiacal positions occupied by the sun in successive months -- reinforcing the solar cycle, at a slower pace. Suppose Jupiter rises from the mansion of Yingshi 營室 as a morning star in some year, and the sun rises from the same position in January of that year. In the February of the next year, the sun rises in the mansion of Dongbi 東壁, which is in the next "station" easterly of Yingshi, at the same time Jupiter has already moved and stayed in Yingshi for roughly a month15. In the Chapter of Celestial Governors (Tianguanshu 天官書) of the Shiji, Si Maqian 司馬遷 left a more detailed description of the synodic cycle of Jupiter to us: 376 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) The Jupiter rises, traveling east twelve degrees for roughly 100 days, and hesitates. Later on it starts to retrograde, eight degrees for 100 days, and again traveling eastbound.16 He also provides a brief but useful introduction to the judgment of the prograde and retrograde motions of the planet: To know about Jupiter's progression and retrogression, it is necessary to observe the motions of the sun and the moon.17 And the planet becomes some rather marked phenomenon according to the same literature: During the past 100 years, none of the five planets did not commit retrogression after they rose, and the moment they converted from hesitation to retrogression they become dazzling, and their colors altered.18 Furthermore, in the Inner Canon of Huangdi (Huangdi neijing 黃帝内經) Emperor Huang (Huangdi 黃帝) and Elder Qi (Qibo 歧伯) discussed the synodic period of Jupiter in a more descriptive prose with astrological comments as well: The emperor raises the question, "How does the motions (of the Jupiter) vary between quick and slow paces, prograde and retrograde motions?" Elder Qi answered, "If the planet hesitates for long and gets shrinking in shape, it is an alert to meditate on current affairs. If it leaves and comes back soon after and turns around, it is an alert to reflect on past mistakes. If it lingers about, it is time to discuss coming disasters and the virtue of the planet." 19 It is quite clear that not only prograde and retrograde motions, but the variation of the paces had also come into the ken of the observers then. 377 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) Figure 1: the Analog Chart of the Apparent Orbit of the Jupiter The above three sources have clearly delineated the whole process of the synodic period of the Jupiter. They are combined to represent the achievement of the planet observation in the early years of Western Han Dynasty. It is a considerable achievement in people’s eyes today, especially whenever the precision of data in the Divination of the Five Planets is mentioned. The formulation and development of some school of observational astronomy in ancient China along with their observational technology and achievements were rather slow processes of accumulation, according to Joseph Needham, much slower than that of common affairs in daily life, whatever political, economic, or even cultural. Therefore, it is reasonable to deduce that the recognition and some less sophisticated grasp of the synodic period can possibly happen roughly a hundred years (as the time span is also mentioned in Shiji cited before in the paper) before then, that is, the middle and late Warring States period when the Chu silk manuscript came into formulation. Secondly, though "progression", "hesitation", or "retrogression" did not appear in the Jupiter part of the Divination of the Five Planets straightaway, the correspondent astrological hints were all actually displayed in the text. To dispel the vagueness of those hints and uncover the truth, it is necessary to give exact astronomical explanations of the key conceptions of Ying 贏 (exceed), Suo 縮 (recede) and Niu 紐 (knot) in the text. "Yingsuo" 贏縮 (exceed and recede, used inseparably in Chinese) are common jargons of astrologers that outlasted both the ancient and medieval China. It was widely used in descriptions of motions of planets, and later on in the delineation of the regular changes of the traveling speed of the sun and moon. "Yingsuo" was considered regular and even basic motions of the five planets then. Si Maqian wrote of it clearly enough: The five planets are the five assistants of the Heaven. Their visibility and invisibility, as well as progression and retrogression all obey certain laws.20 In traditional Chinese astrological materials we often encounter some apparently astronomical descriptions, which were actually more of people's astrological imagination than astronomical phenomena, for example, the drastically changed vision of shapes or colors of the stars. Obviously “Yingsuo” does not fall into this category in accordance with Si Maqian’s statement. So it is necessary to investigate more exactly, and more astronomically in my view, into the group of astrological concepts to repair the omission we formerly committed Both the Chapter of Celestial Governors in Shiji and the Chapter of Patterns of the Sky 天文志 in Hanshu 漢書 had defined “Yingsuo” in their own prose: With its motions of progression and retrogression, Jupiter looms over the correspondent countries. The country over which Jupiter lingers cannot be invaded, yet it owns the advantage to attack other countries. Whenever it exceeds some She 舍 (stellar house), it commits Ying. Whenever it recedes some She, it commits Suo.21 378 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) Where the Jupiter hangs over cannot be attacked, yet has the advantage to attack others. Ying is for Jupiter to exceed some She, and Suo to recede.22 Besides, Ban Gu made it more clearly of the phenomenon in the Chapter of Calendars (Lvlizhi 律曆志): Yingsuo. The Zuo Traditions said, "Jupiter abandoned the Ci 次 (station) of this year and exceeds into the Ci of the next year, resulting in the hazard to Niaonu and disasters to Zhou 周 and Chu 楚." The Yingsuo of the five planets is no irregular error at all. When Jupiter exceeds the Ci it will cause great disaster, while exceeds the She will evoke merely less serious misfortune. When there is no any exceeds, there is nothing wrong.23 Some similar data can also be drawn from the Prognostic Canon of "Opened Epoch" of Great Tang (Kaiyuan zhan jing 開元占經). In chapter 23 of Jupiter divination, the the Tradition of the Five Elements (Wuxing Zhuan 五行傳) was cited: Ying is for Jupiter to exceed some She, and Suo to recede. When it commits Ying, there will be wars in the country; when suo, there will be worrisome affairs in the country. And the Jingzhou Divination (Jingzhou Zhan 荊州占) was also cited: When Jupiter exceeds the proper She and into the further next, next two or next three She, it is called Ying. Consequently the kings and vassals will have worrisome affairs, or else the sky splits and the ground shakes. When Jupiter recedes the proper She and into the next, next two or next three She behind, it is called Suo. Consequently the kings and vassals will have sad affairs, and in three years there will be wars. The mountains break down and the ground shakes. Whenever Jupiter retrogresses, it will emanate comets in the correspondent mansion, one of which is Tianbei 天棓 (the tine of Heaven), one Tiancheng 天 槍 (the speargun of Heaven), one Tianchan 天欃 (the spear of Heaven) and one Tianfu 天茀 (the sharp grass of Heaven). And in the Jupiter part of the Divination of the Five Planets there are records that are rather similar to the Jingzhou Divination: If Jupiter misses the proper Ci for the former, former two or three She, it is called Suo of Heaven; 【 there will be worrisome affairs in the correspondent country.The country is to be defeated. If Jupiter misses the proper Ci for the next, next two or three She, it is called Ying of Heaven.】During the year there will be flood. And the sky splits, or else the ground shakes. Niu shares the same results in divination.24 Ban Gu had wrote it quite clear in the Chapter of Calendar, that the "Yingsuo" was little relative to Jupiter's eccentric motion "Shici", to which I have given a brief explanation in note 6. Though the word "Ci" appears in the statement of the Divination of the Five Planets, it can in no way equals the twelve stations of the 379 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) Jupiter cycle, that is, the twelve zodiacal divisions measured out by Jupiter. As we all know, the eccentric motion of "Shici" is caused by the gap between the true period of revolution of 11.86 years and the conceptual period of 12 years. It is the discord between man-made chessboard and heaven-driven chessmen. As the erroneous timing accumulates, Jupiter will inevitably and predictably exceeds the supposed-properly-situated station into the next one. However, the error accumulates in merely one direction and no possibility in the opposite direction ever exists. "Receding the proper Ci" will never come to be astronomically true for Jupiter. As a matter of fact, if we investigate into "Suo" individually we find no other explanation but the "retrogression" of the planet for it, which had been put down with certain precision in Shiji cited formerly in this paper. Yet it does not naturally follow that "Ying" corresponds progression, which is basically the common status of Jupiter, thus can in no way meet the astrological need of irregularity. During a synodic period the superior planets obey the following rule: easternmost conjunction→westernmost →stationary→opposition→stationary→ →conjunction quadrature quadrature ︱← prograde →∣ ← retrograde →∣ ← prograde →∣ ∣ ① ∣ ∣ ② ∣ In the two stages of progression, the two mouths right after some conjunction and the two mouths right before the next conjunction, as I marked with ① and ② in the chart, are worth concerning, during which the traveling speed of Jupiter is unusually high. Because of the astrological nature and common usage of the concept “Ying”, I do not employ any accurate reckoning or diagrams to fix the time periods mathematically. The astrological element in this sort of prognosis was not so much a matter of celestial events and movements, but of interpretative arts. Therefore, the true astronomical process cannot impose any restrictions in the best sense of the word on the astrologers, when they did not intend to be rigorous without their habitual ambiguousness. Thus I am inclined to believe that the special time spans are merely sources for the random omen takings in its pragmatic sense. It is the very duty and right for prognosticators to section and select. The “quick paces” described in the Huangdi neijing undoubtedly belong to the two time spans. In other words, if Jupiter is astrologically defined in the motion of Ying by the observer, it must fall into the special periods astronomically. In addition, the phenomenon of "Niu" which "shares the same results in divination" in the Divination of the Five Planets is very likely to be a figurative hint of Jupiter's stationary motion. The pronunciations of the two characters "Niu" (knot) and "Liu" (the stationary motion) are similar in ancient Chinese. Additionally, "She" was frequently employed as unit of measure in the divination of Yingsuo. However, it cannot help us understand the phenomenon properly in terms of its astrological randomness. In comparison with the standard unit system of "Zhang 丈", "Chi 尺" and "Cun 寸" before Western Han and the entry degrees into mansions after, She turned out to be only a figurative utilization derived from the 28 stellar 380 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) mansions (Ershiba she 二 十 八 舍 )25. The respective breaths of the 28 lodges constantly varied according to people’s observations and calculations in different times. Thus the unit of measure She can be merely understood as the mathematical division of the equator, that is, 12.86 degrees average. Data drawn from relative materials can help verify the hypothesis. In Hanshu it wrote: (Venus) rises in the East, travels through four She for 48 days, stands for 20 days and descends in the East at last. It rises in the West, travels through four She for 48 days, stands for 20 days and descends in the West at last.26 The elongation of Venus to the sun can reach the maximum of 47 degrees, which was represented in the Chinese traditional record above as "four She". Therefore a single She equals 11.75 degrees. The two amounts roughly tally in terms of naked-eye observation. Since the hypothesis of She was proved, the descriptions of Jupiter motions in She can all be converted into numerical terms. For example, the “next, next two and three She” both appeared in the Divination of the Five Planets and Hanshu drew an arch of more than 32 degrees against the star background, which was however supposed to be the route of Jupiter during its one time of Ying. This could hardly come to be astronomically true for the planet advances but roughly 30 degrees per year. Moreover, the truth was also correctly recorded in the same source. They are combined to demonstrate the dubious usage of She was not a result of people’s inaccuracy in observation but its intrinsic character of random prognostication. Another example of Mars can contribute its weight to the conclusion as well. In the Chapter of Composition of Music (Zhiyuepian 製樂篇) in Lvshichunqiu 呂氏春秋 it wrote: In the reign of Songjing King (Songjing gong 宋景公), once the Dazzling Dluder (Yinghuo 熒惑) lingers about the Xin 心 lodge. The king asked Ziwei 子韋 about it. Ziwei answered, "The disaster looms over the king, but it can be transferred to the prime minister." The king said, "The prime minister has promised the duty to assist in administering the country (so that he should not be the one to face the disaster)." Ziwei said, "then it can be transferred to common people." The king opposed, "If people were all slayed, whose king would I myself be?" Ziwei went on, "It can be transferred to the Year (Sui, 歲)." The king said, "Human beings would undoubtedly die if the Year went ruined. If I myself, as a king, kill people in this way, who will admit in my being the governor?" Ziwei concluded, "You have made three remarks that show your extreme virtues and kindness, so that you are surely to be awarded by the Heaven. The Dazzling Deluder will move away for three She". Later on the Dazzling Deluder shifted as expected. Mars here is supposed to travel three She, that is, more than 30 degrees in a rather short time. Yet in Shiji people then also demonstrated their rather precise grasp of paces of Mars: The Dazzling Deluder takes a faster pace of 1.5 degrees daily when it travels eastbound.27 Again the ends cannot meet if She is to be restricted to accurate mathematical units of measure. Therefore, it is reasonable to reach the conclusion that She cannot be 381 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) properly employed to understand the phenomenon Yingsuo correctly. Being the basic motions of Jupiter, conceptions like "Ying" and "Suo" are widely seen, and systematically organized in all types of Jupiter divination in later times. And the divination concerning the two usually occupies the initial part of whatever Jupiter divination. In a more primitive style as compared to the astrology in medieval China, the Jupiter divination in the Divination of the Five Planets merely relied on two major groups of omens, one the "Yingsuo", the other the "Jingtui" 進退 (advance and retreat). Again we consult the sources of astronomical phenomena and find no other comparables but the one that fits the "Yingsuo". We can neither discriminate the two according to the way of recording in the other two astrological literatures, in the Chapter of Celestial Governors of Shiji, the omen descriptions being "Yingsuo", while in the Chapter of Sky Patterns in Hanshu the one appearing as "Jintui". The difference between "Yingsuo" and "Jintui" in the Divination of the Five Planets turns out to be a man-made one. The intentional product betrays the significance of the divination concerning motions of exceeds and recedes in Jupiter divination. The last point I would like to press on is the Jupiter ephemerides' incorporation into almanacs. The particularly chosen ephemerides in the diagram of the Divination of the Five Planets are displayed as points of “chen chu dongfang” 晨出東方 (Jupiter’s rising from the East as a morning star)28. When Jupiter emerges from the sun in the morning, it just overtakes the sun and journeys away from the light of it. The phenomenon happens right after a conjunction. I tabulated the data in the diagram in a clearer style in the following: st Rising in the East with Yingshi 營室 The 1 year of Qinshi Emperor 29 reign 秦 始皇元年 Rising in the East with Dongbi 東 壁 2 Rising in the East with Lou 婁 3 Rising in the East with Bi 畢 4 rd 5 th 7 th 6 th 【8 】 th 7 th 【9 】 th 8 th 【40 】 3 nd 4 rd 5 th 6 th 9 nd 【2 】77 th 【10 】 th 1 st 【4 】79 2 nd 【5 】80 th 382 th th rd 【3 】78 th th Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) Rising in the East with Dongjin g 東井 th 7 th 8 th 9 th th 1 5 Rising in 6 the East with Liu 柳 Rising in the East with Zhang 張 7 Rising in the East with Zhen 軫 8 Rising in the East with Kang 亢 9 th th 9 ·The 1 year of Han 漢元·The st 【1 】 year of Huixiao emperor 孝 惠【元】 th 30 th 1 st 【3 】 20 2 nd 【4 】 st 3 rd 5 nd 4 th rd 5 th 6 th Rising in 10 the East with Xin 心 2 st 3 nd 4 Rising in the East with Dou 斗 1 Rising in the East with Xunv 婺 女 2 th st th 2 nd 2 nd th 【6 】81 th 【7 】82 rd 【3 】 rd th th 4 th 【1 】84 th 5 th 2 nd 85 6 th 6 th 3 rd 86 th 7 th 7 th 87 th 8 th · Dai emperor 代 皇 【8 】83 st 88 The Jupiter motions from the first year of the reign of Qinshi Emperor to the fifth year of the reign of Hanwen Emperor are kept in the chart. The teams contain the years every-twelve grouped. And the rows consist of successive years. The certain star mansion that accompanies the morning star Jupiter, among the 28 mansions, occupies the beginning part of every row30. Hinging on the point of "rising in the East as a morning star", the synodic period of Jupiter had been incorporated into the almanac neatly. Such interest and effort of astrologers can be seen again, in our later discussion of the Sui chapter of the Chu silk 383 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) manuscript. A New Interpretation of the Sui Chapter31 All the materials above about the synodic period of Jupiter, it seems, come to jointly demonstrate the maturing knowledge of planets owned by people in early Western Han. Yet today we do not pay attention to the achievement sufficiently while studying relative materials. The knowledge, in my view, can serve as a key to unravel the mystery of Sui Chapter of the manuscript. The “Sui Chapter” dubbed with “Sui” 歲 (Year or a brief form of Year star) was actually about the Year Star, which is the special appellation of Jupiter in traditional Chinese astrology. And the content of the chapter was occupied by the description of the planet’s motions in a synodic period and certain taboo related to the phenomenon. Zheng Gang shared the same point of view with me to some extent, pointing out the whole chapter hinges on the motions of Jupiter. However, connecting the comets caused by Yingsuo described in the text with those in Jupiter divination (as I cited formerly in this paper), he assumed that the chapter was about the eccentric motion Shici32. I have demonstrated in the last section that “Yingsuo” had little relationship with “Shici”. Moreover, all the conceptions of time appearing in the chapter were confined to month and day. They were hardly possible to be included into the Jupiter cycle of twelve years. In another sense, the abnormal "Shici" would render little negative effects on the common calendar measured out by solar years. Thus the Sui Chapter in no way concerned Jupiter cycle. By citing the months and days as important evidence to oppose the view of Jupiter cycle, I intend to particularly discuss the problem of them, which comes to be most difficult and puzzling for researchers. They were included respectively in line three and line four of the chapter: 李歲□月,内(入)月七日、八日,□又(有) (霧) (霜)雨土, 不得其參職。天雨喜喜,□是 (失)月,閏之勿行:一月、二月、三月, 是胃(謂) (失)終亡,奉□□其邦。四月、五月是胃(謂)亂紀亡。 (Li year □ month, entering into the month for seven or eight days. □ fog, frost and rain of soil. Yet it does not turn out to be effective. It rains dauntingly. □missing the month, no intercalary should be utilized: the first, second and the third months being the end of subversion; while the fourth and fifth month being the end of chaos.) (In Chinese the expression of “seven days” can equal that of “the 7th day” literally, meanwhile the expression of “the first month” or “one month” can equal January. So my interpretation of the text adapts to my own understanding, leaving the controversy caused by the possible confusions of the translation to discuss later. ) Li Xueqin considered “Qiri, bari”(七日, 八日) to be “the 7th and 8th days of some month”33. And almost all the researchers hold or acquiesce in the view that "Yiyue, eryue,sanyue" (一月、二月、三月) and "siyue, wuyue" (四月、五月) represent January, 384 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) February, March, April and May. Shang Chengzuo assumed that the funeral and related activities of the tomb owner would explain for the time concepts34. The owner died in January and was buried in May according to certain rituals. However, the Sui Chapter cared little about individual welfare or private affairs if it is exploited from the grand. Instead the chapter is suffused with judicial atmosphere and furnished with the basic logic of “theory of correspondences” as Schafer once defined traditional Chinese astrology35. Furthermore, the most serious defect of this explanation is that the “Yiyue, eryue sanyue” and “Siyue, wuyue” were not historically proper appellations for the months from January to May. In the inscription of Ding of Chu King 楚王 鼎 January was called "Zhengyue". Since the Western Zhou founded its reign the months were often called "wang ji yue" 王幾月 (some month of the King). What’s more important is the discovery of the unique system of months' appellations of Chu people themselves. The system has been displayed in various unearthed materials, like the Jiudian bamboo strips, Shuihudi bamboo strips and the fragmental pieces of silk manuscript excavated from the same site of the manuscript now we focus36. The first five months of a year are successively called Dongluan 冬 , Quluan 屈 , Yuanluan 遠 , Jingshi 荊尸 and Xiashi 夏尸 other than the simple ordinals. Chen Mengjia tried to reconcile the discripancey, raising the usage of "Yiyue" in oracle-bone inscriptions37. Dong Zuobing used to dicuss "Yiyue" and "Zhengyue" in Shang inscriptions and found that in early years of Shang 商 "Yiyue" was used and later replaced by "Zhengyue"38. Why Chu people in middle and late Warring States period should resume the old habit of Shang Dynasty remains dubious. Liu Xinfang also supported the view by proposing that the set of months was about the arrangement of leap months39. However, it comes to be an established historical fact that before the Taichu Calendar 太初曆 in Western Han the intercalary month was fixed down at the end of the year. The more sophisticated method with flexibility was the fruit of the advances in people’s handle of calendrical technology in later times. Therefore, the months mentioned in the text are more likely to be common ordinals without particularity of fixed positions in a year. As a matter of fact, the sort of time expressions is frequently seen in astrological literatures. In the Mixed Divination of Sky Patterns and Meteorology (Tian wen qi xiang za zhan 天文氣象雑占) it said: In two months the country will go into chaos. Elsewhere in the same source we find: Baiguan (a type of comet) appears. In five days there will be rebellions in the country.40 So it is in the Chapter of Celestial Governors in Shiji, where we read: When (Jupiter) advances in the Northeast, it emanates Tianbei (the Tine of Heaven) in three months; ...when it advances in the Southeast, it procreates a comet; ...when it recedes in the Northwest, it emanates Tianchan (the Spear of 385 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) Heaven); ...when it recedes in the Southwest, it emanates Tiancheng (the Spear gun of Heaven). Similar records can also be found in the Chapter of Sky Patterns of Hanshu, and in later times, countless of them with more complicated appearances can be found in literatures like Kaiyuan zhanjing and Yi si zhan 乙巳占 (the Yisi Divination). The time expressions do not serve common calendars. In comparison with fixed months and days in almanacs, they act as numbers more than as ordinals. The months and days in the Sui chapter share the same characteristics with them. Yet there still exists a major difference between the two, for the time concepts in the manuscript are astronomically meaningful. The Sui chapter was originally divided into three parts with red square marks, with part 1 from "隹 □月則 (贏)絀不 (得) (其)(當)" to "是月以 為 之正隹十又二歲□", part 2 from "隹(惟)李 匿" to "敬之毋隔(忒)",and part 3 all the rest of the text. In part 1 the retrogression and hesitation of Jupiter in an abnormal sydonic period, and the ghostly emanations produced within the process were delineated. Part 2 turns to press on the understanding of the sydonic period's incorporation into the common calendar, and methods of shunning the disasters mentioned in part 1. In the last part, people were warned that if they do not frequently practice the sacrifice, negative effects would be rendered on the their civil construction. The theme of synodic period of Jupiter penetrates the whole text. 隹□□□四月則贏絀不得其當。 There are mainly two ways to punctuate the initial sentence of the chapter, one as "惟 十又(有)四月,則贏絀不得其當", proposed by Li Ling in 1985 yet later abandoned41; the other as "隹□□□四,月則贏絀不得其當" supported by most scholars. The major difference between the two views turns out to be the subject located before the predicate "Yingchu" 贏絀 (which is an equivalent of "Yingsuo"). In the more applauded one moon is supposed to commit “Yingsuo”, that is, to engage in irregular movements of exceed and recede. When used specially in astronomical and astrological records of moon, the jargon "Yingsuo" serves to indicate the constant variation of its speed. However, the first awareness of such variation occurred in the Eastern Han Dynasty42. In Western Han people had merely a primitive handle of the average traveling speed of the moon. Chen Jiujin proposed that the earliest record of perigee of moon available appeared in the Commentary on the Five Orders (Wujilun, 五紀論 )by Liu Xiang in late Western Han43: During the journey towards Qianniu and Dongjing (both are star mansions), the moon travels 15 degrees daily. During that towards Lou and Jiao, it travels 13 degrees. It is the equator that causes the difference. It is hardly possible to push the scientific awareness through hundreds of years upward to the times when Chu manuscript was composed. Thus the second way of punctuation, though generally accepted, cannot be firmly established in terms of historical background. 386 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) If the first punctuation is employed, the whole sentence turns out to be “Entering the 14th month, □ exceeds and recedes irregularly.” The subject is literally omitted. Li Ling had previously proposed that the whole sentence was about an erroneous 14th month in a solar year44. The evidence of this type of occurrence can indeed be found in the ocacle-bone inscriptions of Huang group 黃 組 in late Shang Dynasty according to Chang Yuzhu’s research45. However, the explanation cannot satisfactorily repair the omission of the subject. Neither a year nor the 14th month can exceed and recede in any sense. Liu Xinfang regarded the "exceed and recede" as figurative expressions of length changes of lunar months. Yet it is merely a hypothesis without any sound evidence46. The 14th month is indeed an error, but of the synodic period of Jupiter instead of a solar year. It has demonstrated formerly in this paper that people then considered the synodic period to be a length of 13 months. However, the true span of time exceeds the conceptual one 3.44 days. As a result, every ten years the ending point of some synodic period, or in its preferred sense, a time of rising as a morning star, will drift forward into the 14th month. Consequently all the periods of prograde and retrograde motions will shift away from what they were supposed to be fixed in. It is Jupiter that "exceeds and recedes irregularly". If not intentionally plotted out, the stages marked out by the characteristic phenomena of Jupiter do not actually cooperate with daily-used calendars. All the irregularities mentioned in the text are man-made products emanated inevitably from the gap between people's conceptual systems of different knowledge. And that is why such strange description as "the sun, moon and planets went into disorder, ... the four seasons stayed imperturbable." (日月星辰,亂 逆其行,...春夏秋冬,又(有)□常.) And the apparently paradoxical thing is repeated in part 2 of the chapter. (贏)絀 (失)□,卉木亡尚(常),是(?)【謂】夭(妖)。天地 乍(作) ,天 (棓) 將乍(作) (湯),降於其方。山陵其發(廢), 又(有) (淵)厥 (汩),是胃(謂)李。 The character was commonly accepted as " ". Later in 1986 Zheng Gang proposed that it should be " ". And newly discovered evidence in Shangbo Chu bamboos confirmed his hypothesis. In the Sui chapter "Li" 李 appears for three times. Except the first appearance in the citation above, the other two are: In line 2—3: 李歲□月,内(入)月七日、八日,□又(有) (霧) (霜)雨土, 不得其參職。 Elsewhere in line 7: 隹(惟)李 匿,出自黃 (淵),土身亡□,出内(入)□同,乍(作) 其下凶。 There exists quite a dilemma in the explanation of the "Li". The first two are successive in position, which were formerly understood as comets emanated by Jupiter. But for the last one the explanation does not make sense. Liu Xinfang 387 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) assumed that "Li" represented "Tianli", an alias of Mars (usually called Yinghuo, the Dazzling Deluder in Chinese astrological literature)47. The new assumption fits the last "Li" quite well, however in no way suits the former two. The first "Li" parallels "Yao" 夭 grammatically, with the "Tianbei" (the tine of Heaven) inserted between them. In accordance with the citations from the Divination of the Five Planets, Shiji and Hanshu formerly in this paper, "Yao" and "Tianbei" are special appellations for the emanated comets of Jupiter. If the first two "Li" represent Mars, it will be rather far-fetched to connect true Mars parallel with those ghostly apparitions of people's astrological imagination. The condition gets worse for the second "Li", for it is located right before "Sui" 歲, Jupiter as we know. It is grammatically possible for “Li” to be an adnominal of “Sui”, yet not for the case of Mars and Jupiter in their real sense. There is, furthermore, neither any internal clue to legalize the coexistence of the two planets according to the text. Thus neither of the two solutions can satisfy the three appearances simultaneously. The crux is, summarily, the three "Li" turn out to be of abstract or substantial character respectively in accordance of grammar and textual environment. Therefore, I incline to believe the condition is actually separate. The first two "Li", grouped together represent fancied emanations of Jupiter, and the remaining one indicates Mars. The usage of the appellation "Li" in astronomical sense in Han Dynasty allowed the separation, as a matter of fact. The name "Tianli" 天李 (the Plum of Heaven) of Mars, which mainly indicates the shape and orange luster is much more rarely seen in textual records in comparison with its phonic derivative "Tianli" 天理 (the Reason of Heaven), which had been politically and morally elaborated in later times. In the Chapter of Sky Patterns in Hanshu, the heavenly plum "Li" appeared: In July, the 4th year, the Dazzling Deluder (Mars) overtook the Year Star (Jupiter), and stayed in the Northeast of it. The two planets looked like successively posited Li (plums)48. Obviously in the record the plum Li had not been specially confined to indicate Mars. The description attests to the figurative nature of "Li", not particularly for Mars but also for other sparkling ball-like celestial bodies. The first two “Li” in the manuscript are likely to fall into this category as a common figuration of stars. To affirm that the first two "Li" like their counterpart "Yao" are fancied comets in Jupiter divinations, I would like to present two pieces of eternal evidence of the text. In the first place, the description "其行 絀逆□,卉木亡尚□ 宎" with the general address form Yao 宎 contained anticipated the conjoining phenomena Li, Tianbei and Yao in the sense of syntax. Secondly, the series of time conceptions as I have discussed before are astronomically meaningful to depict a stationary and retrograde section of the synodic period of Jupiter. Li, Tianbei and Yao were totally included in the process just like what was displayed in Jupiter divinations elsewhere. The "seven and eight days" represent the 388 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) process of stationary motion. The following fog, frost, rain of soil as well as excessive rain all echoed the hesitation of Jupiter. In modern astronomy the stationary motion lasts only one day according to the precision modern science concerns and handles with. However, in ancient China, even in medieval China several hundred years thereafter, the stationary motion was supposed to last more than a week49. For the naked-eye ancient observers, in roughly a week's time the variation of the apparent right ascension of Jupiter before its retrogression could hardly be recognized50. In the Divination of the Five Planets, where Niu indicated the stationary motion, the daunting eccentricity was also connected with excessive rain. The retrogression came as soon as the hesitation ended, and, in a nice correspondence, the following controversial "five months" in the text turned to delineate the retrograde motion. The retrograde period had always been separated into two sections as marked out by Jupiter's opposition to the sun in traditional Chinese astronomical records. The two sections were clearly defined as former and latter retrogressions in Tang times, while in the times of Shiji the division was also mentioned in a more obscure language. Early in times of Chu silk manuscript, the "Yiyue, eryue and sanyue" indicated the regression before opposition, and the “siyue, wuyue" the one after. Though separated, they still remained part of retrograde period, that is, time of abnormality boded ill. That is why the first three months was defined as the time of subversion, while the following two the time of chaos. Therefore, harbored by the whole process of stationary and retrograde motions the abnormal celestial bodies Li, Tianbei and Yao could be none other than comets adjunct to Jupiter's motion changes. The third Li will be discussed after the clarification of the key conception “ 匿”. 凡歲 匿,女(如)□□□隹(?)邦所五(?)天之行,卉木民人 以□四淺之尚(常)。□□上夭,三寺(時)是行。隹(惟)德匿之歲,三 寺(時)是行。隹(惟) 匿之歲,三寺(時)既(?)□, 之以 降。 It is time now to reconsider the conception of the most controversy 匿, which is also the one of the most significance in the chapter. The former debate focuses on whether " " should be "Ceni" 側匿 (an astronomical phenomenon) or "Deni" 德 匿 (the concealment of virtues)51. In terms of all the above analysis of the content of the chapter, the conception should be considered more astronomically in my view. "Ceni", cited from the record of moon observation "朔而月見東方謂之側匿" (If the moon is still visible when it comes to be Shuo 朔, the phenomenon is called Ceni), indicates the delay of the end of the cycle of moon phases. Meanwhile when the conception was employed to depict the movements of Jupiter, it correspondently represents the delay of the end of one synodic cycle of the planet, that is, the very abnormality of the 14th month mentioned at the beginning of the Sui chapter. In addition, another totally new concept "Suiji" 歲季, appearing later in the text, seems to reinforce my point of view. The statement of "歲季乃□,寺雨進退,亡又尚恆, 恭(恐)民未知,曆以爲則毋童(動)" clearly informed us that the moves of "Suiji", the season of Sui literally, could not be mixed up in common calendars; If not understood by laymen, ill results would be imposed on them. To review the apparently 389 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) paradoxical statement of disordered heavenly bodies and imperturbable seasons, and the awareness to incorporate Jupiter ephemeris into calendars in the Divination of the Five Planets, I feel quite obliged to immediately link "Suiji", the season of Jupiter, with the synodic period of Jupiter. Consequently, it was Suiji that committed the eccentricity of Ceni, as the manuscript defined eternally. 隹李 匿,出自黃 (淵),土身亡□, 出内 同,乍(作)其下凶。 Of this sentence Liu Xinfang raised the assumption that it was about the Ceni of Mars, as for the third appearance of Li52. And Huangyuan 黃淵 (the yellow abyss) is understood to be the conceptual void where stars end their east-to-west journey and fall into, partly and literally for ancient Chinese named the zodiac as the yellow road. Moreover, Saturn also shows up in here in terms of Rao Zongyi53 and Liu Xinfang's analysis. The similar event of Mars and Saturn were raised to adjunct to the commentary of Jupiter's Ceni. The statement "出内 同,作其下凶" (The entry and entrance were the same. ...Ill results would also happen underneath) turns out to be a simple comparison between them. The question is why is the Mars and Saturn, but not Mercury or Venus or all of the five planets? Again for some astronomical reason, the problem can be satisfactorily solved. As we know, being the inferior planets, Mercury and Venus can never opposite the sun in their orbits. They come to be visible only as morning and evening stars. The distinct difference naturally tells them from the other three, which are grouped as superior planets. Possibilities for inferior planets. Mercury and Venus, as they 'pass in front of' the earth can only be seen at certain angles relative to the sun. Wherever the earth is in its orbit Venus & Mercury will be seen relatively close to the sun. Possibilities for superior planets. Mars, Jupiter & Saturn, as they 'pass behind' the earth can be seen at all angles relative to the sun. Figure 2: the Figure of Possibilities for Both Inferior and Superior Planets 54 Furthermore, a perfectly comparable record is available in the Divination of the Five Planets. Albeit the records of the other three planets were abundantly furnished with observational data, the ones for Mercury and Saturn strangely turned out to be purely astrological and extremely simple. According to Yabutti, the omission of Mercury might be the outcome of the difficulty to observe the planet for its proximity to the sun, and the omission of Saturn might be a matter of convenience for its extreme similarity to Jupiter55. The two points not only help us in understanding the selective appearance of planets in the manuscript, but the way and sequence they appeared to 390 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) be in. Summarily, along with the theme of the synodic period of Jupiter, the Sui chapter of Chu silk manuscript turns out to be orderly and reasonably organized. The manuscript is among the earliest attempts to make sense of the synodic period of Jupiter, though appearing rather obscure. It attested to the speculative interest emerged alongside the mythologies inherited from earlier times. At the end of this paper I would like again to review the discussion the nature of the manuscript as an organic whole. The manuscript included all the elements of early history, astronomical observation data, astrological concerns as well as related taboos. It was excavated in a middle-sized tomb owned by a Shi 士 56, common intellectual other than a vassal or a king who deserves the concern of countries and wars occupied the manuscript. Some researchers treated it like a tool of wizardry, which was supposed to protect the tomb owner from certain disasters. However, both the content and the physical appearance of the material makes it not that proper to be comparable with the manuscripts unearthed in Mawangdui Tomb or the almanacs Rishu 日書 which seemed more of practical handbooks. To take all of its advanced knowledge of planets, the refined language, calligraphy and appearance into account, I believe it is a piece of individual writing with a nature of classics though I cannot easily assume that the tomb owner is the very author. Served both as astronomers and astrologers in the sense of modern science, the officials or intellectuals in ancient times had gradually developed both expertise in observation and divination57. The Chu Silk Manuscript comes to show us some cross section of the development. The Calculation for the Analog Chart of the Apparent Orbit of the Jupiter The model is founded to imitate the relationship of the Sun, the Earth and Jupiter (without considerations for the eccentricity of Jupiter and the inclining angle of its orbit.) The Earth E and Jupiter J revolute the Sun S. Let the Sun occupies the origin of the coordinate. In the coordinate vector r1 points to the Earth E, and vector r2 points to Jupiter J.In the ancient observers’ eyes, the Sun and Jupiter revolted the Earth. Therefore the changes of vector r1, 2 are to demonstrate the conditions of Jupiter’s revolution about the Earth. 391 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) x1 r1 cos(1t ) r1 : y1 r1 sin( 1t ) x2 r2 cos( 2 t ) r2 : y 2 r2 sin( 2 t ) x2 x1 r2 cos( 2 t ) r1 cos(1t ) r1, 2 : y 2 y1 r2 sin( 2 t ) r1 sin( 1t ) The distance between the Sun and Earth: r1 = 1 astronomical unit, The distance between the Sun and Jupiter: r2 = 5.2astronomical unit. The angle speed of Jupiter’s revolution about the Sun: 2 2 = 1 = 365.256 *11.86 4331.936 The angle speed of Earth’s revolution about the Sun: 2 2 = 365.25 Suppose the direction of axis x is that of ecliptic longitude. The variation of the included angle between vector r1, 2 and axis x equals the change of apparent ecliptic longitude of Jupiter. L arctg ( r2 sin( 2 t ) r1 sin( 1t ) ) r2 cos( 2 t ) r1 cos(1t ) Put r1 , r2 , 1 and 2 into the equation. T ranges from 0 to 2000. The unit of time is day. And finally make the chart out of the values of L calculated from the equation. 致谢 女士对本科生科研的支持,尤其感谢他们对 感谢李政道先生及其夫人秦惠 新兴交叉学科的鼓励。 感谢导师朱凤瀚先生,感谢先生百忙之中指导我启动项目,并一直给我和风 细雨般的鼓励。 感谢导师荣新江先生,感谢先生在学术圣殿前为我开启大门,并给我一路教 诲和关爱,给我以学术为业的信仰。 感谢导师李零先生,先生睿智渊博,指点教诲之间,赐我诸多启示和反思。 一日为师,终身为父。 感谢东京大学易平君替我翻译日文文献。 392 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) 感谢物理学院吴焰立君和清华大学吴东君为我提供技术支持。 感谢同班同学孙正军君一直以来对我研究工作的关心和匡正。 感谢室友陈甜、廖娟和郑妙思诸君一直以来给我的支持、温情和友爱。 隆情高谊,理应感铭。 感谢爸爸妈妈。 1 For a general survey of the literatures on the study of the Chu silk manuscript, see Li Ling Changsha zidanku zhanguo chuboshu yanjiu (Bejing: Zhonghua shuju, 1985); and “Changsha zidanku zhanguo chuboshu yanjiu buzheng”, in the Conference on the Celebration of a Decade of the Society of Ancient Chinese Character Scripts study (Changchun: 1986); and in Guwenzi yanjiu (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2000), Vol.20, pp.154--178; Zeng Xiantong “Chuboshu yanjiu shuyao”, in Rao Zongyi and Zeng Xiantong Chudi chutu wenxian sanzhong yanjiu (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1993), pp.362—404. For a recent overview of new researches from 1990 to 2003, see Xu Xueren “Changsha zidanku zhangguo chuboshu yanjiu wenxian yaomu” (http://www.jianbo.org/Mlhc/2003/xuxueren03.htm). 2 The view was first suggested in Dong Zuobing “Lun changsha chutu zhi zengshu”, Dalu zazhi, 1955:10,pp.173--177. And it gradually comes to be the major theme to discuss the structure of the manuscript. See Chen Mengjia “Zhanguo chuboshu kao”, Kaogu xuebao, 1984:2, pp.137--158; Li Ling “Chuboshu yu shitu”, Jianghan kaogu, 1991:1, pp.59--62 and Zhongguo fanshukao (Beiing: Dongfang Press, 2000), pp.189--190; and Chen Maoren “You chuboshu zhitu fangshi lun qi xingzhi”, in Xianqian lianghan luncong, ed. the Department of Chinese Literature in Furen University (Taibei: Hongye Press, 1999), pp.299--341. 3 Shang Chengzuo, “Zhanguo chuboshu shulue”, Wenwu, 1964:9, p.19. 4 Li Xueqin, “Lun chuboshu zhong de tianxiang”, Hunan kaogu jikan (1982 )Vol.1; also in Jianbo yiji yu xueshu shi (Taibei: Shibao, 1994), p.42. 6 It is both astronomical and astrological tradition to divide the zodiac, in its sense of convenience, a perfect cycle into averagely twelve parts. As to mark the motions and orbit of Jupiter, each one-twelfth-of-the-cycle serves as a station of the planet. In traditional Chinese star wisdom the period of revolution of Jupiter was supposed to be solid twelve years. Consequently the planet measures out year by year, as a chronometer, the twelve zodiacal positions occupied by the sun in successive months – reinforcing the solar cycle, as it were, at a slower pace. Actually the complete passage of the ecliptic by Jupiter takes a little less than twelve years, 11.86 years exactly – a fact to which popular astrology was blind. Whenever Jupiter exceeds some station according to people’s twelve-year-a-cycle reason, however predictable this advent, it is supposed to portend ill fortune for the place, person or political agency. The eccentric phenomenon is named “Shici” (missing the station) in traditional astrological literature. 5 See Rao Zongyi “Chuboshu zhi neihan jiqi xingzhi shihuo”, in Chudi chutu wenxian sanzhong yanjiu (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1993), pp.303—318; and Zheng Gang, “Chuboshu zhong de xingsuijinian he suixingzhan”, in Jianbo yanjiu (Beijing: Falv Press, 1996), Vol.2, ed. Li Xueqin, pp.59--68. 7 Li Ling, “Changsha zidanku boshu yanjiu buzheng”, p.164. 8 Li Ling, “Changsha zidanku boshu yanjiu buzheng”, p.163. 9 Liu Xiaolu, "Zhongguo bohua yanjiu 50 nian", Zhonggu wenhua yanjiu 1995: the winter volume, pp. 126. 10 Shang Chengzuo, "Zhanguo chuboshu shulue", p.19. 11 Rong Zongyi, "Chuboshu zhi shufa yishu", Chudi chutu wenxian sanzhong yanjiu, p.341. 12 Li Ling, "Changsha zidanku chuboshu yanjiu buzheng", p.162. 13 Li Dongsheng suggested in his "Lun woguo gudai wuxing huihe zhouqi he hengxing zhouqi de ceding" (Ziran kexue shi yanjiu, 1987:3, pp.224—237) that as early as in Pre-Qin period the conceptions of synodic and stellar periods had already come into formulation. He drew the conclusion from the ancient astrological materials cited by thus kept in the Kai Yuan zhan jing. However, this type of sources in Kai yuan zhan jing, though abundantly existed, should be cautiously treated for part of them had come through revisions and adjustments and no longer 393 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) showed up in their original ancient appearance. Therefore, the conclusion of Western Han can be more reliable. 14 It is translated from the original text unscrambled by the research group of Mawangdui Han Tomb. See Zhongguo tianwenxueshi wenji Vol.1 (Beijing: Science Press, 1978), pp.1--13. 15 See the original text, pp.9—10. 16 Shiji (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1967) 27.1313. 17 Shiji.27.1312. 18 Shiji.27.1350. 19 Huangdi neijing, the Wenyuange sikuquanshu edition, (Taibei: Shangwu, 1967) pp.232--233. 20 Shiji.27.1350. 21 Shiji.27.1312. 22 Hanshu.26.1280. 23 Hanshu.24.1005. 24 the original text, p.2. 25 See both the Shiji.27.1314 and Hanshu.26.1277. 26 Hanshu.26.1281. 27 Shiji. 27. 1314. 28 There used to be some debate on the real meaning of "chen chu dong fang" description. He Youqi questioned the explanation offered by the collators of the text. See “Shi lun wuxinzhan de shidai he neirong”, Xueshu yanjiu 1979:1, pp.79--87; and “Ping qianjia jian guanyu taisui taiyin de yichang zhenglun”, Xueshu yanjiu, 1979:5, pp.102--108. Later Chen Jiujin wrote to defend the original explanation. See "Guanyu suixing jinian ruogan wenti", Xueshu yanjiu, 1980:6, pp.82--87. 29 To test the credibility of the timing departure, Yabutti employed ancient data from Planetary, Lunar, and Solar Positions, 601 B.C. to A. D.by B. Tuckerman to compare the ecliptic longitude of the sun and Jupiter in different records, and successively demonstrated that the first "chen chu dongfang" happened in the first year of Qinshihuang reign was only fabrication of astrologers. See “Guanyu mawangdui sanhao hanmu chutu de wuxingzhan”, Kexueshi yicong, 1964:1, p.54. 30 For the analysis of the structure of the chart, see Yabutti "Guanyu mawangdui sanhao hanmu chutu de wuxingzhan", p.54. Also see Xi zongze "Zhongguo tianwenxueshi de yige zhongyao faxian ---- mawangdui hanmu boshu zhong de wuxingzhan", Zhongguo tianwenxueshi wenji, pp.14--33; and Chen Jiujin "Cong mawangdui wuxingzhan de chutu shitan woguo gudai de suixingjinian wenti", pp.34--46. 31 All the photographs of the manuscript as raw materials for this paper are obtained from Rong Zongyi and Zeng Xiantong Chudi chutu wenxian sanzhong yanjiu, the picture part: pp. 65—102. 32 Zheng Gang, “Chuboshu zhong de xingsuijinian he suixingzhan”, pp.59—68. 33 Li Xueqin, "Lun chuboshu zhong de tianxiang", p.40. 34 Shang Chengzuo, "Zhanguo chuboshu shulue", p.19. 35 See Edward H. Schafer Pacing the Void -- T'ang Approaches to the Stars, (LA: University of California Press, 1977), p.55. 36 For a brief introduction of these fragmentary manuscipt, see Shang Zhifu "Ji Shangchengzuo jiaoshou cang changsha zidanku chuguo can boshu", Wenwu, 1992:11, pp.32--35; and in the same volume Rong Zongyi "Changsha zidanku wenzi xiaoji", pp.34--35; and Li Xueqin "Shi lun changsha zidanku chuboshu canpian", pp.36--39. For the intoduction of the month appellations, see Li Ling "Du jizhong chutu faxian de xuanzelei gushu", Jianbo yanjiu Vol.3,ed. Li Xueqin and Xie Guihua, (Guangxi: Jiaoyu, 1998), pp.96--104. 37 See Chen Mengjia "Zhanguo chuboshu kao", Kaogu xuebao, 1984:2, p.140. 38 See Dong Zuobing "Yinli zhong jige zhongyao wenti", Shiyusuo jikan, 1934:4, the 3rd division, pp.331--353. 39 See Liu Xinfang "Chuboshu lungang", Huexue Vol.2 (Guangzhou: Zhongshan University Press, 1996), pp.53--60; also in his own collection Zidanku chumu chutu wenxian yanjiu (Taibei: Yiwen yinshuguan, 2002). 40 The unscrambled and revised text of the manuscript is collected in the Zhongguo fangshu gaiguan, the volume of astrology, ed. Li Ling, (Beijing: Renmin zhongguo Press, 1993), pp.10--11. 41 Li Ling, Changsha zidanku zhanguo chuboshu yanjiu, p.51. 394 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) 42 See Qian Baozong "Hanren yuexing yanjiu", Qianbaozong kexueshi lunwen xuanji, ed. Zhongguokexueyuan zirankexueshi yanjiusuo, (Beijing: Science Press, 1983), pp. 175--192; and formerly published in Yanjing xuebao, Vol.17, 1935. 43 Chen Jiujin "Jiudaoshu jie", Ziran kexueshi yanjiu, 1982:2, pp.131--135. 44 Li Ling, Changsha zidanku zhanguo chuboshu yanjiu, p.51. 45 Chang Yuzhi Shangdai zhouji zhidu, (Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue Press, 1987), pp.227--291. Or else see the Yinshang lifa yanjiu, (Jilin: wenshi Press, 1998), p.305. 46 Liu Xinfang, "Chuboshu lungang", p.56. 47 Liu Xinfang, "Chuboshu lungang", p.56. 48 Hanshu.26.1279. 49 See Niu Weixing And Jiang Xiaoyuan "Qiyaorangzaijue muxing libiao yanjiu", Zhongguo kexueyuan shanghai tianwentai niankan, 1997:8, pp.241--249; also in their own collection Tianwen xixuedongjian ji,(Shanghai: Shanghai shudian Press,2000), pp.130--142. 50 Take the stationary motion happened on November 3rd, 2001 for example, the hour angle right on the day is 7h08m02.073s. From October 30th to November 5th, the hour angle lingers between 7h07m56.245s and 7h08m02.073s. The range of changes is confined into 2s. The data are drawn from 2001nian Zhongguo tianwen nianli (Beijing: Science Press, 2002). 51 For a brief surey of the debate, see Liu Xinfang "Chuboshu 'deni' yiji xiangguan wenzi de shidu", Huaxue Vol.5, (Guangzhou: Zhongshan university Press, 2001), pp.130—142. 52 See Liu Xinfang "Chuboshu 'deni' yiji xiangguan wenzi de shidu", Huaxue Vol.5, p. 133. 53 See Rao Zongyi "Chuboshu xinzheng", Chudi chutu wenxian yanjiu, p.261. 54 The chart is quoted from http://www.ucl.ac.uk/sts/gregory/msc/handouts/ho06-a&c.doc. See Yabutti “Guanyu mawangdui sanhao hanmu chutu de wuxingzhan”, p.54. See Hunan Museum "Changsha zidanku zhanguo muguomu", Wenwu, 1974:2, pp. 36--43. 57 See Li Xueqin "Heguanzi yu liangzhong boshu", Daojia wenhua yanjiu Vol.1, (Shanghai: Shanghai guji Press, 1992); also in Jianbo yiji yu xueshu shi, p.95. Also see Wang Mengou "Yinyang wuxingjia yu xingli ji zhanshi", Shiyusuo jikan, Vol. 43, the 3rd division, 1973, pp. 489--532. 55 56 作者简介:左娅,女,1982 年 6 月 16 日出生于湖北省武汉市,2000 年因连续两 次获全国中学生英语口语竞赛特等奖、湖北省第二名保送入北京大学历史学系学 习至今。本科学习期间,对中国古代科技史,特别是天文学史抱有浓厚兴趣。 2000—2001 学年获侨心奖学金,校三好学生;2001—2002 学年获宝钢奖学金。 感悟与寄语:尽最大可能地投入去做一件事,追寻一次真相,承受并享受一次独 立探索新知的全过程,是最难忘的经历之一。因为投入的不仅仅是时间和精力, 还有开始时的憧憬和希望、过程中的激动和焦灼、结束时开始的下一轮希望。 我热爱智慧和知识纯粹存在着的学术世界,绝非虚言,因为它是这样一个美丽新 世界。 指导教师简介: 朱凤瀚先生,男,1947 年 7 月出生于北京,江苏淮安人。现任中国历史博 物馆馆长,北京大学历史系博士生导师。主要研究先秦史、中国古文字(甲骨文、 金文)和中国古代青铜器。 荣新江先生,男,1960 年生于天津。现任北京大学历史系教授、博士生导 师。主要研究方向为汉唐中西文化交流、唐五代西北民族史、西域史、敦煌吐鲁 番文书、敦煌古籍整理。 395 Series of Selected Papers from Chun-Tsung Scholars,Peking University(2003) 李零先生,男,山西武乡人,1948 年生,北京大学中文系教授、博士生 导师。主要研究方向为简帛文献与学术源流, 《孙子兵法》研究,中国方术研究, 《左传》,中国古代文明史,海外汉学研究,中国古代兵法。 396