Virginia's CP Outline

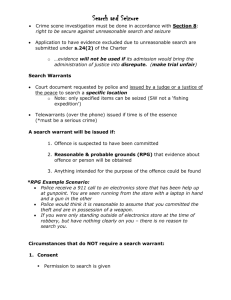

advertisement