Terms -- AP English Language and Composition

advertisement

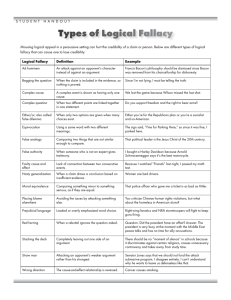

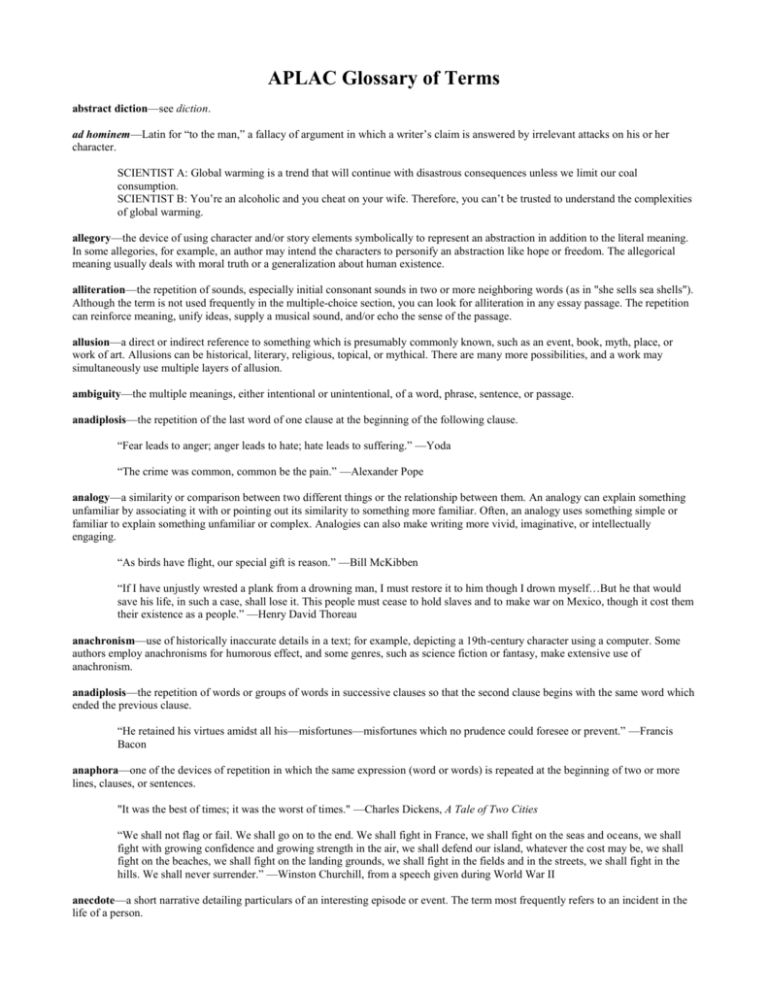

APLAC Glossary of Terms abstract diction—see diction. ad hominem—Latin for “to the man,” a fallacy of argument in which a writer’s claim is answered by irrelevant attacks on his or her character. SCIENTIST A: Global warming is a trend that will continue with disastrous consequences unless we limit our coal consumption. SCIENTIST B: You’re an alcoholic and you cheat on your wife. Therefore, you can’t be trusted to understand the complexities of global warming. allegory—the device of using character and/or story elements symbolically to represent an abstraction in addition to the literal meaning. In some allegories, for example, an author may intend the characters to personify an abstraction like hope or freedom. The allegorical meaning usually deals with moral truth or a generalization about human existence. alliteration—the repetition of sounds, especially initial consonant sounds in two or more neighboring words (as in "she sells sea shells"). Although the term is not used frequently in the multiple-choice section, you can look for alliteration in any essay passage. The repetition can reinforce meaning, unify ideas, supply a musical sound, and/or echo the sense of the passage. allusion—a direct or indirect reference to something which is presumably commonly known, such as an event, book, myth, place, or work of art. Allusions can be historical, literary, religious, topical, or mythical. There are many more possibilities, and a work may simultaneously use multiple layers of allusion. ambiguity—the multiple meanings, either intentional or unintentional, of a word, phrase, sentence, or passage. anadiplosis—the repetition of the last word of one clause at the beginning of the following clause. “Fear leads to anger; anger leads to hate; hate leads to suffering.” —Yoda “The crime was common, common be the pain.” —Alexander Pope analogy—a similarity or comparison between two different things or the relationship between them. An analogy can explain something unfamiliar by associating it with or pointing out its similarity to something more familiar. Often, an analogy uses something simple or familiar to explain something unfamiliar or complex. Analogies can also make writing more vivid, imaginative, or intellectually engaging. “As birds have flight, our special gift is reason.” —Bill McKibben “If I have unjustly wrested a plank from a drowning man, I must restore it to him though I drown myself…But he that would save his life, in such a case, shall lose it. This people must cease to hold slaves and to make war on Mexico, though it cost them their existence as a people.” —Henry David Thoreau anachronism—use of historically inaccurate details in a text; for example, depicting a 19th-century character using a computer. Some authors employ anachronisms for humorous effect, and some genres, such as science fiction or fantasy, make extensive use of anachronism. anadiplosis—the repetition of words or groups of words in successive clauses so that the second clause begins with the same word which ended the previous clause. “He retained his virtues amidst all his—misfortunes—misfortunes which no prudence could foresee or prevent.” —Francis Bacon anaphora—one of the devices of repetition in which the same expression (word or words) is repeated at the beginning of two or more lines, clauses, or sentences. "It was the best of times; it was the worst of times." —Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities “We shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills. We shall never surrender.” —Winston Churchill, from a speech given during World War II anecdote—a short narrative detailing particulars of an interesting episode or event. The term most frequently refers to an incident in the life of a person. APELC Glossary of Terms annotation—the taking of notes directly on a text; annotation is an essential skill in the close reading of a text. As you read a text, circle unknown words, identify main ideas and words, phrases, or sentences that appeal to you. Look for imagery and figurative language. Underline interesting or unusual syntax. In the margins, write notes, ask question, or use symbols to indicate important passages. Annotation should help you determine the meaning of a text, the rhetorical strategies the author’s uses, and how those devices affect the meaning. antecedent—the word, phrase, or clause referred to by a pronoun. The AP language exam occasionally asks for the antecedent of a given pronoun in a long, complex sentence or in a group of sentences. When the car starts making that horrible clunking noise, it needs to be taken to the mechanic. Car is the antecedent to which the pronoun it refers. antimetabole—a rhetorical device in which the same words or ideas are repeated in transposed order. “Eat to live, not live to eat.” —Socrates “We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock. Plymouth Rock landed on us.” —Malcolm X antithesis—opposition, or contrast of ideas or words in a parallel construction; the presentation of two contrasting ideas which are balanced by word, phrase, clause, or paragraphs. “To err is human; to forgive divine.” —Alexander Pope, “An Essay on Criticism” “Patience is bitter, but is has a sweet fruit.” —Aristotle aphorism—a terse statement of known authorship which expresses a general truth or a moral principle. (If the authorship is unknown, the statement is generally considered to be a folk proverb.) An aphorism can be a memorable summation of the author's point. “Dream as if you’ll live forever. Live as if you’ll die tomorrow.” —James Dean “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire.” apostrophe—a figure of speech that directly addresses an absent or imaginary person or a personified abstraction, such as liberty or love. It is an address to someone or something that cannot answer. The effect may add familiarity or emotional intensity. In his sonnet, “London, 1802,” William Wordsworth addresses John Milton (1608-1674) as he writes, "Milton! thou shouldst be living at this hour: / England hath need of thee." appeal to false authority—a fallacy of argument in which a claim is based on the expertise of someone who lacks appropriate credentials. This type of fallacy is commonly seen in advertising when celebrities are used to hock products with which they have no expertise. ACTOR: I’m not a doctor, but I play one on TV. You trust me when I say that Super Relief 2000 is the fastest acting, most effective medicine you can take to cure your most acute aches and pains. appositive—a word or group of words placed beside a noun or noun substitute to supplement its meaning or rename it. Nonrestrictive appositives (appositives that are inessential to the meaning of the sentence) are usually set off by commas, parentheses, or dashes. “The Otis Elevator Company, the world’s largest and biggest elevator manufacturer, claims that its products carry the equivalent of the world’s population every five days.”—Nick Paumgartne, “Up and Then Down.” The New Yorker, 2008 "I have had the great honor to have played with these great veteran ballplayers on my left--Murderers Row, our championship team of 1927. I have had the further honor of living with and playing with these men on my right--the Bronx Bombers, the Yankees of today." —Gary Cooper as Lou Gehrig, The Pride of the Yankees, 1942 argument—1. Spoken, written, or visual text that expresses a point of view; 2. The use of evidence and reason to discover some version of the truth, as distinct from persuasion, the attempt to change someone else’s point of view. assertion—a statement that presents a claim or thesis. assonance—the repetition of similar or identical vowel sounds in words that begin with differ consonant sounds and are close to one another within a sentence or within several sentences within a paragraph. “And the stars never rise, but I feel the bright eyes / Of the beautiful Annabel Lee; / And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side / Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride.” —Edgar Allan Poe, “Annabel Lee” 2 APELC Glossary of Terms assumption—a belief regarded as true, upon which other claims are based. asyndeton—a rhetorical device in which conjunctions between phrases in a sentence are eliminated, yet the sentence maintains grammatical accuracy. When an asyndeton is used in a series of words, phrases, or clauses, it suggest the series is somehow incomplete, that there is more the writer could have included. Asyndeton can also create ironic juxtapositions that invite readers in a relationship with the writer—because there may be no explicit connections between the words, phrases, or clauses, the reader is left to infer the author’s intent. Asyndeton can also quicken the pace of prose. “This villain among you who deceived you, who meant to betray you completely…” —Aristole, Rhetoric “I have found the warm caves in the woods, filled them with skillets, carvings, shelves, closets, silks, innumerable goods.” —Anne Sexton, “Her Kind” atmosphere—the emotional mood created by the entirety of a literary work, established partly by the setting and partly by the author's choice of objects that are described. Even such elements as a description of the weather can contribute to the atmosphere. Frequently atmosphere foreshadows events. Perhaps it can create a mood. audience—the person or persons to whom an argument is directed; the listener, viewer, or reader of a text. Most texts are likely to have multiple audiences. authority—the quality conveyed by a writer who is knowledgeable about his or her subject and confident in that knowledge. backing—in Toulmin argument, the evidence provided to support a warrant. bandwagon appeal (ad populum)—a fallacy of argument in which a course of action is recommended on the grounds that everyone else is following it. For example, if your friends get you to jump off a bridge by telling you that everyone else is jumping off the bridge, you would be guilty of “jumping on the bandwagon.” bathos—a literary term derived from a Greek word meaning “depth,” bathos is when a writer uses inconsequential and absurd metaphors, descriptions, or ideas in an effort to be overly emotional or passionate. Do not confuse bathos with pathos. While the term originally referred to blunders inadvertently committed by writers, comic writers have changed the meaning of the terms as they use it to refer to intentionally maudlin, or bathetic, writing. begging the question—a form of circular reasoning; a fallacy of argument in which a claim is based on the very grounds that are in doubt or dispute. Maria has never stolen anything. She can’t be the bicycle thief. cacophony—harsh, awkward, or dissonant sounds used deliberately in poetry or prose; the opposite of euphony. “‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves / Did gyre and gimble in the wabe; / All mimsy were the borogoves, / And the mome raths outgrabe.” —Lewis Carroll, “The Jabberwocky” cadence—the rising and falling rhythm of speech especially in free verse or prose. caricature—descriptive writing that greatly exaggerates a specific feature of a person’s appearance or a facet of personality. catharsis—purification or cleansing of the spirit through the emotions of pity and terror as a witness to a tragedy. chiasmus—a rhetorical device in which two or more clauses are balanced against each other by the reversal of their structures in order to produce and artistic effect. “The instinct of a man is to pursue everything that flies from him, and to fly from all that pursues him.” —Voltaire circular reasoning—a type of reasoning in which the proposition is supported by the premises, which is supported by the proposition, creating a circle in reasoning where no useful information is being shared. LOGICAL FORM: X is true because of Y. Y is true because of X. Piracy is wrong because it is against the law, and it’s against the law because it is wrong. circumlocution—the use of an unnecessarily large number of words to express an idea. “I was within a hair’s breadth of the last opportunity for pronouncement, and I found with humiliation that probably I would have nothing to say…” —Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest 3 APELC Glossary of Terms clause—a grammatical unit that contains both a subject and a verb. An independent, or main, clause expresses a complete thought and can stand alone as a sentence. A dependent, or subordinate, clause cannot stand alone as a sentence and must be accompanied by an independent clause. The point that you want to consider is the question of what or why the author subordinates one element to the other. You should also become aware of making effective use of subordination in your own writing. claim—a statement that asserts a belief or truth. claim of fact—a claim of fact asserts that something is true or not true. “The number of suicides and homicides committed by teenagers, most often young men, has exploded in the last three decades...” —Anna Quindlen claim of value—a claim of value argues that something is good or bad, right or wrong. “There’s a plague on all our houses, and since it doesn’t announce itself with lumps or spots or protest marches, it has gone unremarked in the quiet suburbs, and busy cities where it has been laying waste.” —Anna Quindlen claim of policy—a claim of policy proposes a change. “Yet one solution continues to elude us, and that is ending the ignorance about mental health, and moving it from the margins of care and into the mainstream where it belongs.” —Anna Quindlen closed thesis—a closed thesis is a statement of the main idea of the argument that also previews the major points the writer intends to make. The three-dimensional characters, exciting plot, and complex themes of the Harry Potter series make then not only legendary children’s books but also enduring literary classics. coherence—a principle demanding that the parts of any composition be arranged so that the meaning of the whole may be immediately clear and intelligible. Words, phrases, clauses within the sentence; and sentences, paragraphs, and chapters in larger pieces of writing are the units that, by their progressive and logical arrangement, make for coherence. colloquial/colloquialism—the use of slang or informalities in speech or writing. Not generally acceptable for formal writing, colloquialisms give a work a conversational, familiar tone. Colloquial expressions in writing include local or regional dialects. complex sentence—a sentence that includes one independent clause and at least one dependent clause. “If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer.” —Henry David Thoreau, Walden compound sentence—a sentence that includes at least two independent clauses. Compound sentences can be formed in three ways: 1. using coordinating conjunction (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so); 2. using a semicolon, either with or without conjunctive adverbs; 3. (on occasion) using the colon. “They may take our lives, but they will never take our freedom.” —Mel Gibson as William Wallace in Braveheart “Always go to other people’s funerals; otherwise, they won’t go to yours.” — Yogi Berra “Arguments are to be avoided: they are always vulgar and often convincing.” —Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest compound-complex sentence—a sentence with one complex sentence jointed to a simple sentence with a conjunction. “Those are my principle, and if you don’t like them…well, I have others.” —Groucho Marx conceit—a fanciful expression, usually in the form of an extended metaphor or surprising analogy between seemingly dissimilar objects. A conceit displays intellectual cleverness as a result of the unusual comparison being made. concession—an acknowledgment that an opposing argument may be true or reasonable. In a strong argument, a concession is usually accompanied by a refutation challenging the validity of the opposing argument. conclusion (peroratio)—the fifth part of the five-part argument structure of classical oration; the conclusion bring the argument to a satisfying close by summarizing the case and moving the audience to action. concrete diction—see diction. 4 APELC Glossary of Terms confirmation (confirmatio)—the third part of the five-part argument structure of classical oration; usually the major part of the text, the confirmation includes the proof needed to make the writer’s case. The rhetor offers detailed support for the claim, including both logical reasoning and factual evidence. connotation—the nonliteral, associative meaning of a word; the implied, suggested meaning. Connotations may involve ideas, emotions, or attitudes. consonance—the repetition of identical consonant sounds within two or more words in close proximity, as in boost/best; it can also be seen within several compound words, such as fulfill and ping-pong. “Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking / Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore— / What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt and ominous bird of yore / Meant in croaking “Nevermore.”” —Edgar Allan Poe, “The Raven” context—the entire situation in which a piece of writing takes place, including the writer’s purpose(s) for writing; the intended audience; the time and place of writing; the institutional, social, personal, and other influences on the piece of writing (whether it’s, for instance, online or on paper, in handwriting or print); and the writer’s attitude toward the subject and the audience. counterargument—an opposing argument to the one a writer is putting forward. Rather than ignoring a counterargument, a strong writer will usually address it through the process of concession and refutation. counterargument thesis—a thesis statement in which a summary of a counterargument, usually qualified by although or but, and precedes the writer’s opinion. Although the Harry Potter series may have some literary merit, its popularity has less to do with storytelling than with merchandising. cumulative (loose) sentence—an independent clause followed by a series of subordinate constructions (phrases or clauses) that gather details about a person, place, event, or idea. Contrast with a periodic sentence. “I write this at a wide desk in a pine shed as I always do in these recent years, in this life I pray will last, while the summer sun closes the sky to Orion and to all the other winter stars over my roof.” —Annie Dillard, An American Childhood declarative sentence—a sentence in the form of a statement. “Friends and fellow citizens, I stand before you tonight under indictment for the alleged crime of having voted at the last presidential election, without having a lawful right to vote.” —Susan B. Anthony, On Woman’s Right to Vote deduction—deduction is a logical process whereby one reaches a conclusion by starting with a general principle or universal truth (a major premise) and applying it to a specific case (a minor premise). The process of deduction is usually demonstrated in the form of a syllogism: MAJOR PREMISE: Eating fruit is healthy. MINOR PREMISE: Bananas are a type of fruit. CONCLUSION: Eating bananas is good for my health. denotation—the strict, literal, dictionary definition of a word, devoid of any emotion, attitude, or color. dialect—the use of words, phrases, grammatical constructions and sounds that capture everyday (or colloquial) language; dialect shows the actual way people speak, which often differs markedly from standard English. diatribe—a bitter, sharply abusive denunciation, attack, or criticism. diction—related to style, diction refers to the writer's word choices, especially with regard to their correctness, clearness, or effectiveness. For the AP exam, you should be able to describe an author's diction (for example, formal or informal, ornate or plain) and understand the ways in which diction can complement the author's purpose. Diction, combined with syntax, figurative language, literary devices, etc., creates an author's style. Abstract diction refers to language that describes concepts rather than concrete images (ideas and qualities rather than observable or specific things, people, or places). For example, terms such as love, peace, justice, and intelligence are abstract as they cannot be seen, felt, smelled, tasted, or heard—in other words, they cannot be perceived by the five senses. Words that describe the observable or “physical” are examples of concrete diction. Powerful writing/speaking avoids abstract language and, instead, includes concrete language that allows the audience to better perceive the writer’s experience. discourse—written or spoken communication or debate. 5 APELC Glossary of Terms double entendre—a figure of speech or a particular way of wording that is devised to be understood in either of two ways, having a double meaning. NURSE: God ye good morrow, gentlemen. MERCUTIO: God ye good den, fair gentlewoman. NURSE: Is it good den? MERCUTIO: ‘Tis no less, I tell you; for the bawdy hand of the dial is now upon the prick of noon. NURSE: Out upon you! What a man are you! dysphemism—a figure of speech which is defined as the use of disparaging or offensive expressions instead of inoffensive ones, such as croaked, kicked the bucket, and bit the dust for deceased. either/or fallacy (false dilemma)—a fallacy of argument in which a complicated issue is misrepresented as offering only two possible alternatives, one of which is often made to seem vastly preferable to the other. You either with God, or you are against him. enthymeme—in Toulmin argument, a statement that links a claim to a supporting reason: The bank will fail (claim) because it has lost the support of its largest investors (reason). In classical rhetoric, an enthymeme is a syllogism with one term understood but not stated: Socrates is mortal because he is a human being. (The understood term is: All human beings are mortal.) epigram—a pithy saying or remark expressing an idea in a clever and amusing way. “I can resist anything except temptation.” —Oscar Wilde, The Importance of Being Earnest epigraph—a phrase, quotation, or poem that is set at the beginning of a document or component. The epigraph may serve as a preface, as a summary, as a counter example, or to link the work to another text. epiphany—a sudden, intuitive perception of or insight into the reality or essential meaning of something. epistolary—relating to, or denoting, the writing of letter or literary works in the form of letters. epitaph—a phrase or statement written in memory of a person who has died, especially as an inscription on a tombstone. epithet—an adjective or descriptive phrase expressing a quality characteristic of the person mentioned. In the Odyssey, Homer refers to Odysseus as “master mariner,” “man of many resources,” and “the great glory of the Achaeans.” epistrophe—a rhetoric device that uses repetition at the end of successive clauses; the opposite of anaphora. “They saw no evil, they spoke no evil, and they heard no evil.” equivocation—a logical fallacy in which an ambiguous term is used in more than one sense, making the argument misleading. DRIVER: The sign said fine for parking here, and since it was fine, I parked there. ethos—Greek for character, the self-image a writer creates to define a relationship with readers. In arguments, most writers try to establish an ethos that suggests authority and credibility. Ethos is established both by who you are and what you say. eulogy—a speech or writing in praise of a person (or thing), especially one recently dead or retired. euphemism—from the Greek for "good speech," euphemisms are a more agreeable or less offensive substitute for a generally unpleasant word or concept. The euphemism may be used to adhere to standards of social or political correctness or to add humor or ironic understatement. Saying "earthly remains" rather than "corpse" is an example of euphemism. euphony—a succession of harmonious sounds used in poetry or prose; the opposite of cacophony. evidence—material offered to support an argument. exclamatory sentence—a type of sentence that expresses strong feelings by making an exclamation. Exclamatory sentences are ended with an exclamation mark. “I can’t believe it! Reading and writing actually paid off!” —Homer Simpson, The Simpsons exigence—an issue, problem, or situation that causes or prompts someone to write or speak. expletive—an offensive word or phrase (such as “Damn it!”) that people sometimes say when they are angry or in pain. 6 APELC Glossary of Terms exposition—in essays, one of the for chief types of composition, the others being argumentation, description, and narration. The purpose of exposition is to explain something. In drama, the exposition is the introductory material, which creates the tone, gives the setting, and introduces the characters and conflict. extended metaphor—a metaphor developed at great length, occurring frequently in or throughout a work. faulty analogy—a logical fallacy in which a comparison between two objects or concepts is inaccurate or inconsequential. MEDICAL STUDENT: “No one objects to a physician looking up a difficult case in medical books. Why, then, shouldn’t students taking a difficult exam be permitted to use their textbooks.” figurative language—writing or speech that is not intended to carry literal meaning and is usually meant to be imaginative and vivid. figure of speech—a device used to produce figurative language. Many compare dissimilar things. Figures of speech include apostrophe, hyperbole, irony, litotes, metaphor, metonymy, oxymoron, paradox, personification, simile, synecdoche, synesthesia, and understatement. first-hand evidence—evidence based on something the writer knows, whether it’s from personal experience, observations, or general knowledge of events. fragment, sentence—a sentence fragment fails to be a sentence because it does not contain an independent clause and cannot stand on its own. Running high up the jagged mountain peak in an attempt to see the sunrise. generic conventions—this term describes traditions for each genre. These conventions help to define each genre; for example, they differentiate an essay and journalistic writing or an autobiography and political writing. On the AP language exam, try to distinguish the unique features of a writer's work from those dictated by convention. genre—the major category into which a literary work fits. The basic divisions of literature are prose, poetry, and drama. However, genre is a flexible term; within these broad boundaries exist many subdivisions that are often called genres themselves. For example, prose can be divided into fiction (novels and short stories) or nonfiction (essays, biographies, autobiographies, etc.). Poetry can be divided into lyric, dramatic, narrative, epic, etc. Drama can be divided into tragedy, comedy, melodrama, farce, etc. On the AP language exam, expect the majority of the passages to be from the following genres: autobiography, biography, diaries, criticism, essays, and journalistic, political, scientific, and nature writing. hasty generalization—a fallacy in which a faulty conclusion is reached because of inadequate evidence. Smoking isn’t bad for you; my great aunt smoked a pack a day and lived to be 90. homily—this term literally means "sermon," but more informally, it can include any serious talk, speech, or lecture involving moral or spiritual advice. hortative sentence—sentence that exhorts, urges, entreats, implores, or calls to action. “Let both sides explore what problems unite us instead of belaboring those problems which divide us.” —John F. Kennedy hyperbole—a figure of speech using deliberate exaggeration or overstatement. Hyperbole often creates a comic effect; however, a serious effect is also possible. Often, hyperbole produces irony. "I was helpless. I did not know what in the world to do. I was quaking from head to foot, and could have hung my hat on my eyes, they stuck out so far." —Mark Twain, "Old Times on the Mississippi" idiom—an express that cannot be understood from the meanings of its separate words but that has a different meaning of its own. Idioms are not interpreted literally—the phrase is understood as to mean something quite different from what the words literally imply. A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush. Don’t look a gift horse in the mouth. imagery—the sensory details or figurative language used to describe, arouse emotion, or represent abstractions. On a physical level, imagery uses terms related to the five senses; we refer to visual, auditory, tactile, gustatory, or olfactory imagery. On a broader and deeper level, however, one image can represent more than one thing. For example, a rose may present visual imagery while also representing the color in a woman's cheeks and/or symbolizing some degree of perfection (It is the highest flower on the Great Chain of Being). An author may use complex imagery while simultaneously employing other figures of speech, especially metaphor and simile. In addition, this term can apply to the total of all the images in a work. On the AP exam, pay attention to how an author creates imagery and to the effect of this imagery. 7 APELC Glossary of Terms imperative sentence—sentence used to command or enjoin. “Carpe diem. Seize the day, boys. Make your lives extraordinary.” —Robin Williams as John Keating in Dead Poets Society induction—from the Latin inducere, “to lead into,” a logical process whereby the writer reasons from particulars to universals, using specific cases in order to draw a conclusion, which is also called a generalization. Regular exercise promotes weight loss. Exercise lowers stress levels. Exercise improves mood and outlook. inference/infer—to draw a reasonable conclusion from the information presented. When a multiple-choice question asks for an inference to be drawn from a passage, the most direct, most reasonable inference is the safest answer choice. If an inference is implausible, it's unlikely to be the correct answer. Note that if the answer choice is directly stated, it is not inferred and is wrong. As we have seen in the multiple-choice selections that we have been trying, you must be careful to note the connotation—negative or positive—of the choices. innuendo—an allusive or indirect remark or hint, typically suggestive, derogatory, or disparaging. “Graze on my lips, and if those hills be dry / Stray lower, where the pleasant fountains lie.” —William Shakespeare, Venus and Adonis interrogative sentence—a sentence that asks a direct question and ends in a question mark. “Where do you want to go today?” —tagline from Microsoft’s first global advertising campaign, 1996 introduction (exordium)—in classical oration, the first part of the five-part structure; a rhetor introduces the subject or problem to an audience while trying to win their attention and good will. invective—an emotionally violent, verbal denunciation or attack using strong, abusive language. inverted sentence—English is an S-V-O language, that is, it usually follows a subject-verb-object construction. Inversion is a reversal of the normal word order, especially the placement of a verb ahead of the subject. “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” —J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit irony/ironic—the contrast between what is stated explicitly and what is really meant. The difference between what appears to be and what actually is true. In general, there are three major types of irony used in language; (1) In verbal irony, the words literally state the opposite of the writer's (or speaker's) true meaning; (2) In situational irony, events turn out the opposite of what was expected. What the characters and readers think ought to happen is not what does happen; (3) In dramatic irony, facts or events are unknown to a character in a play or piece of fiction but known to the reader, audience, or other characters in the work. Irony is used for many reasons, but frequently, it's used to create poignancy or humor. isocolon—a rhetorical device that involves a succession of sentences, phrases, and clauses of grammatically equal length creating parallelism. The device can create pleasing rhythms, and the parallel structures it creates may reinforce a parallel substance in the speaker’s claims. “It takes a licking, but it keeps on ticking!” —advertising slogan of Timex watches jargon—the special language of a profession or group. The term jargon usually has pejorative associations with the implication that jargon is evasive, tedious, and unintelligible to outsiders. juxtaposition—placement of two things closely together to emphasize similarities or differences. “The nations of Asia and Africa are moving at jet-like speed toward gaining political independence, but we still creep at horseand-buggy pace toward gaining a cup of coffee at a lunch counter.” —Martin Luther King kairos—the opportune moment; in arguments, the timeliness of an argument and the most opportune ways to make it. litotes—a figure of speech consisting of an understatement in which an affirmation is expressed by negating its opposite. “We made a difference. We made the city stronger, we made the city freer, and we left her in good hands. All in all, not bad, not bad at all.” —Ronald Reagan, Farewell Address to the Nation, 1989 logical fallacy—logical fallacies are potential vulnerabilities or weaknesses in an argument. They often arise from a failure to make a logical connection between the claim and the evidence used to support it. 8 APELC Glossary of Terms logos—Greek for “embodied thought.” Speakers appeal to logos, or reason, by offering clear, rational ideas and using specific details, examples, facts, statistics, or expert testimony to back them up. loose sentence (cumulative sentence)—a type of sentence in which the main idea (independent clause) comes first, followed by dependent grammatical units such as phrases and clauses. If a period were placed at the end of the independent clause, the clause would be a complete sentence. A work containing many loose sentences often seems informal, relaxed, and conversational. Generally loose sentences create loose style. malapropism—from French mal a propos (inappropriate), the use of an incorrect word in place of a similar sounding word that results in a nonsensical and humorous expression. “There’s no stigmata connected with going to a shrink.”—Little Carmine in The Sopranos metaphor—a figure of speech using implied comparison of seemingly unlike things or the substitution of one for the other, suggesting some similarity. Metaphorical language makes writing more vivid, imaginative, thought provoking, and meaningful. metonymy—a term from the Greek meaning "changed label" or "substitute name," metonymy is a figure of speech in which the name of one object is substituted for that of another closely associated with it. A news release that claims "the White House declared" rather that "the President declared" is using metonymy. The substituted term generally carries a more potent emotional impact. modifier—an adjective, adverb, phrase, or clause that modifies a noun, pronoun, or verb. The purpose of a modifier is usually to describe or focus. Sprawling and dull in class, he came alive in the hallways. mood—this term has two distinct technical meanings in English writing. The first meaning is grammatical and deals with verbal units and a speaker's attitude. The indicative mood is used only for factual sentences. For example, "Joe eats too quickly." The subjunctive mood is used to express conditions contrary to fact. For example, "If I were you, I'd get another job." The imperative mood is used for commands. For example, "Shut the door!" The second meaning of mood is literary, meaning the prevailing atmosphere or emotional aura of a work. Setting, tone, and events can affect the mood. In this usage, mood is similar to tone and atmosphere. narrative—the telling of a story or an account of an event or series of events. narration (narratio)—in classical oration, the second part of the five-part argument structure; provides factual information and background material on the subject at hand or establishes why the subject is a problem that needs addressing. The narratio puts an argument in context by explaining what happened, when it happened, who is involved, and so on. non sequitur—Latin for “it does not follow,” a fallacious argument in which its conclusion does not follow from its premises. RALPH WIGGUM: Martin Luther King had a dream. Dreams are where Elmo and Toy Story had a party and I was invited. Yay! My turn is over! PRINCIPAL SKINNER: One of your best, Ralphie. —"The Color Yellow," The Simpsons, 2010 objectivity—an impersonal presentation of events and characters. It is a writer’s attempt to remove himself or herself from any subjective, personal involvement in a story. Hard news journalism is frequently prized for its objectivity, although even fictional stories can be told without a writer rendering personal judgment. occasion—the time and place a speech is given or a piece is written. onomatopoeia—a figure of speech in which natural sounds are imitated in the sounds of words. Simple examples include such words as buzz, hiss, hum, crack, whinny, and murmur. If you note examples of onomatopoeia in an essay passage, note the effect. open thesis—an open thesis is one that does not list all the points the writer intends to cover in an essay. The popularity of the Harry Potter series demonstrates that simplicity trumps complexity when it comes to the taste of readers, both young and old. oxymoron—from the Greek for "pointedly foolish," an oxymoron is a figure of speech wherein the author groups apparently contradictory terms to suggest a paradox. Simple examples include "jumbo shrimp" and "cruel kindness." This term does not usually appear in the multiple-choice questions, but there is a chance that you might find it in an essay. Take note of the effect which the author achieves with this term. pacing—the speed or tempo of an author’s writing. Writers can use a variety of devices (syntax, polysyndeton, anaphora, meter) to change the pacing of their words. An author’s pacing can be described as fast, sluggish, stabbing, vibrato, staccato, measured, etc. 9 APELC Glossary of Terms paradox—a statement that appears to be self-contradictory or opposed to common sense but upon closer inspection contains some degree of truth or validity. “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others,” —George Orwell, Animal Farm paralipsis (also spelled paralepsis)—a rhetorical strategy (and logical fallacy) of emphasizing a point by seeming to pass over it. "Let's pass swiftly over the vicar's predilection for cream cakes. Let's not dwell on his fetish for Dolly Mixture. Let's not even mention his rapidly increasing girth. No, no—let us instead turn directly to his recent work on self-control and abstinence." —Tom Coates, Plasticbag.org, Apr. 5, 2003 parallelism—also referred to as parallel construction or parallel structure, this term comes from Greek roots meaning "beside one another." It refers to the grammatical or rhetorical framing of words, phrases, sentences, or paragraphs to give structural similarity. This can involve, but is not limited to, repetition of a grammatical element such as a preposition or verbal phrase. A famous example of parallelism begins Charles Dickens's novel A Tale of Two Cities: "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity…" The effects of parallelism are numerous, but frequently they act as an organizing force to attract the reader's attention, add emphasis and organization, or simply provide a musical rhythm. parody—a work that closely imitates the style or content of another with the specific aim of comic effect and/or ridicule. As comedy, parody distorts or exaggerates distinctive features of the original. As ridicule, it mimics the work by repeating and borrowing words, phrases, or characteristics in order to illuminate weaknesses in the original. Well-written parody offers enlightenment about the original, but poorly written parody offers only ineffectual imitation. Usually an audience must grasp literary allusion and understand the work being parodied in order to fully appreciate the nuances of the newer work. Occasionally, however, parodies take on a life of their own and don't require knowledge of the original. pathos—Greek for “suffering” or “experience.” Speakers appeal to pathos to emotionally motivate their audience. More specific appeals to pathos might play on the audience’s values, desires, and hopes, on the one hand, or fears and prejudices, on the other. periodic sentence—a sentence that presents its central meaning in a main clause at the end. This independent clause is preceded by a phrase or clause that cannot stand alone. The effect of a periodic sentence is to add emphasis and structural variety. It is also a much stronger sentence than the loose sentence. "To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men, that is genius." —Ralph Waldo Emerson, "Self-Reliance" persona—Greek for “mask.” The face or character that a speaker shows to his or her audience; the voice or figure of the author who tells and structures the story and who may or may not share of the values of the actual author. personification—a figure of speech in which the author presents or describes concepts, animals, or inanimate objects by endowing them with human attributes or emotions. Personification is used to make these abstractions, animals, or objects appear more vivid to the reader. “Oreo: Milk’s favorite cookie.” —slogan on Oreo’s packaging persuasion—a form of argument; the act of seeking to change someone else’s point of view through appeals to reason or emotion. point of view—in literature, the perspective from which a story is told. There are two general divisions of point of view and many subdivision within those: (1) the first person narrator tells the story with the first person pronoun, "I," and is a character in the story. This narrator can be the protagonist, a participant (character in a secondary role), or an observer (a character who merely watches the action); (2) the third person narrator relates the events with the third person pronouns, "he," "she," and "it." There are two main subdivisions to be aware of: omniscient and limited omniscient. In the "third person omniscient" point of view, the narrator, with godlike knowledge, presents the thoughts and actions of any or all characters. This all-knowing narrator can reveal what each character feels and thinks at any given moment. The "third person limited omniscient" point of view, as its name implies, presents the feelings and thoughts of only one character, presenting only the actions of all remaining characters. This definition applies in questions in the multiple-choice section. However on the essay portion of the exam, the "point of view" carries an additional meaning. When you are asked to analyze the author's point of view, the appropriate point for you to address is the author's attitude. polemic—Greek for “hostile,” an aggressive argument that tries to establish the superiority of one opinion over all the others. Polemics generally do not concede that opposing opinions have any merit. polysyndeton—from a Greek word meaning “bound together,” a stylistic device in which several coordinating conjunctions are used in succession in order to achieve an artistic effect. “Let the whitefolks have their money and power and segregation and sarcasm and big houses and schools and lawns like carpets, and books, and mostly–mostly–let them have their whiteness.” —Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings 10 APELC Glossary of Terms post hoc ergo propter hoc—this fallacy is Latin for “after which therefore because of which,” meaning that it is incorrect to always claim that something is a cause just because it happened earlier. One may loosely summarize this fallacy by saying that correlation does not imply causation. LOGICAL FORM: 1. A occurs before B. 2. Therefore A is the cause of B. ATHLETE: I had been doing pretty poorly this season. Then my girlfriend gave me this neon laces for my spikes and I won my next three races. Those laces must be good luck...if I keep on wearing them I can't help but win! precedents—actions or decisions in the past that have established a pattern or model for subsequent actions. premise—a statement or position regarded as true and upon which other claims are based. propaganda—the spread of ideas and information to further a cause. In its negative sense, propaganda is the use of rumors, lies, disinformation, and scare tactics in order to damage or promote a cause. prose—one of the major divisions of genre, prose refers to fiction and nonfiction, including all its forms. In prose the printer determines the length of the line; in poetry, the poet determines the length of the line. pun—a play on words in which a humorous effect is produced by using a word that suggests two or more meanings or by exploiting similar sounding words having different meanings. Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana. A horse is a very stable animal. purpose—the goal the speaker wants to achieve; the goal of an argument. Purposes include entertaining, informing, convincing, exploring, and deciding, among others. qualifier—words or phrases that limit the scope of a claim, making it less absolute: usually, in a few cases, under these circumstances, etc. qualified argument—an argument that is not absolute. It acknowledges the merits of an opposing view, but it develops a stronger case for its own position. qualitative evidence—evidence supported by reason, tradition, precedent or logic. quantitative evidence—quantitative evidence includes things that can be measured, cited, counted, or otherwise represented in numbers—for instance, statistics, surveys, polls, census information. rapport—a harmonious or sympathetic relationship established between speaker and audience; built through friendly introductions, complimenting, showing respect, and conveying optimism. rebuttal—in the Toulmin model, a rebuttal gives voice to possible objections. Writers need to anticipate such conditions in shaping their arguments. red herring—a type of fallacy that is an irrelevant topic introduced in an argument to divert the attention of the audience from the original issue. A student is caught cheating by his professor and says, “I know I was wrong to cheat, but my parents are going to be so disappointed. They’re going to kill me.” refutation—a denial of the validity of an opposing argument. In order to sound reasonable, refutations often follow a concession that acknowledges that an opposing argument may be true or reasonable. refutation (refutatio)—in classical oration, the fourth part in the five-part argument structure; addresses the counterargument—the rhetor recognizes and refutes opposing claims of evidence. It is a bridge between the writer’s proof and conclusion (peroratio). repetition—the duplication, either exact or approximate, of any element of language, such as a sound, word, phrase, clause, sentence, or grammatical pattern. reservation—in the Toulmin model, a reservation explains the terms and conditions necessitated by the qualifier. rhetor—the speaker who uses elements of rhetoric effectively in oral or written text. 11 APELC Glossary of Terms rhetoric—from the Greek for "orator," this term describes the principles governing the art of writing effectively, eloquently, and persuasively. rhetorical appeals—rhetorical techniques used to persuade an audience by emphasizing what they find most important or compelling. The three major appeals are to ethos (character), logos (reason), and pathos (emotion). rhetorical modes—this flexible term describes the variety, the conventions, and the purposes of the major kinds of writing. The four most common rhetorical modes and their purposes are as follows: (1) The purpose of exposition (or expository writing) is to explain and analyze information by presenting an idea, relevant evidence, and appropriate discussion. The AP language exam essay questions are frequently expository topics; (2) The purpose of argumentation is to prove the validity of an idea, or point of view, by presenting sound reasoning, discussion, and argument that thoroughly convince the reader. Persuasive writing is a type of argumentation having an additional aim of urging some form of action; (3) The purpose of description is to re-create, invent, or visually present a person, place, event, or action so that the reader can picture that being described. Sometimes an author engages all five senses in description; good descriptive writing can be sensuous and picturesque. Descriptive writing may be straightforward and objective or highly emotional and subjective; (4) The purpose of narration is to tell a story or narrate an event or series of events. This writing mode frequently uses the tools of descriptive writing. These four writing modes are sometimes referred to as modes of discourse. rhetorical (Aristotelian) triangle—a diagram that illustrates the interrelationship among the speaker, audience, and subject in determining a text. sarcasm—from the Greek meaning "to tear flesh," sarcasm involves bitter, caustic language that is meant to hurt or ridicule someone or something. It may use irony as a device, but not all ironic statements are sarcastic, that is, intended to ridicule. When well done, sarcasm can be witty and insightful; when poorly done, it's simply cruel. satire—a work that targets human vices and follies or social institutions and conventions for reform or ridicule. Regardless of whether or not the work aims to reform human behavior, satire is best seen as a style of writing rather than a purpose for writing. It can be recognized by the many devices used effectively by the satirist: irony, wit, parody, caricature, hyperbole, understatement, and sarcasm. The effects of satire are varied, depending on the writer's goal, but good satire, often humorous, is thought provoking and insightful about the human condition. second-hand evidence—evidence that is accessed through research, reading, and investigation. It includes factual and historical information, expert opinion, and quantitative data. semantics—the branch of linguistics that studies the meaning of words, their historical and psychological development, their connotations, and their relation to one another. sesquipedalian—from a Latin word meaning “words that are a foot and a half long,” it is a stylistic device defined by the use of words that are very long and have several syllables. “O! they have lived long on the alms basket of words. / I marvel thy master hath not eaten thee for a word; /for thou art not so long by the head as / honorificabilitudinitatibus: thou art easier / swallowed than a flap-dragon….” —William Shakespeare, Love’s Labours Lost shift—a change in tone or mood, accompanied by a change in nuance. The focus may shirt and it is frequently introduced with but or so. simile—A figure of speech used to explain or clarify an idea by comparing it explicitly to something else, using the words like, as, than, or as though. “Zoos are pretty, contained, and accessible…Sort of like a biological Crabtree & Evelyn basket selected with you in mind.” —Joy Williams simple sentence—a sentence with only one independent clause. “Children are all foreigners.” —Ralpho Waldo Emerson slang—an informal nonstandard variety of speech characterized by newly coined and rapidly changing words and phrases. speaker—the person or group who creates a text. This might be a politician who delivers a speech, a commentator who writes an article, an artist who draws a political cartoon, or even a company that commissions an advertisement. stance—a speaker’s attitude toward the audience (differing from tone, the speaker’s attitude toward the subject). straw man fallacy—a fallacy of argument in which a speaker attributes an easily refuted position to his or her opponent, one that the opponent wouldn’t endorse, and then proceed to attack the easily refuted position (straw man) believing you have undermined the opponent’s actual position. 12 APELC Glossary of Terms BOB: The government should put more money into health and education and less into the defense budget. SUE: I can’t believe you hate our country so much that you want to leave it vulnerable to terrorist acts by cutting military spending. Your lack of patriotism is no reason to divert funds from the defense budget. stream of consciousness—a narrative technique that gives the impression of a mind at work, jumping from one observation, sensation, or reflection to the next, usually expressed in a flow of words without conventional transitions. James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, and William Faulkner commonly use stream of consciousness in their writing. style—the consideration of style has two purposes: (1) An evaluation of the sum of the choices an author makes in blending diction, syntax, figurative language, and other literary devices. Some authors' styles are so idiosyncratic that we can quickly recognize works by the same author (or a writer emulating that author's style). Compare, for example, Jonathan Swift to George Orwell or William Faulkner to Ernest Hemingway. We can analyze and describe an author's personal style and make judgments on how appropriate it is to the author's purpose. Styles can be called flowery, explicit, succinct, rambling, bombastic, commonplace, incisive, or laconic, to name only a few examples. (2) Classification of authors to a group and comparison of an author to similar authors. By means of such classification and comparison, we can see how an author's style reflects and helps to define a historical period, such as the Renaissance or the Victorian period, or a literary movement, such as the romantic, transcendental or realist movement. subject—the topic of the text; what the text is about. subject complement—the word (with any accompanying phrases) or clauses that follow a linking verb and complements, or completes, the subject of the sentence by either (1) renaming it or (2) describing it. The former is technically a predicate nominative, the latter a predicate adjective. subjectivity—a personal presentation of evens and characters, influenced by the author’s feelings and opinions. subordinate clause—like all clauses, this word group contains both a subject and a verb (plus any accompanying phrases or modifiers), but unlike the independent clause, the subordinate clause cannot stand alone; it does not express a complete thought. Also called a dependent clause, the subordinate clause depends on a main clause, sometimes called an independent clause, to complete its meaning. Easily recognized key words and phrases usually begin these clauses: although, because, unless, if, even though, since, as soon as, while, who, when, where, how, and that. sweeping generalization—occurs when a writer asserts that a claim applies to all instances instead of some. Children should be seen and not heard. Mozart was a child when he composed his first symphony; therefore, Mozart should not be seen or heard. syllogism—from the Greek for "reckoning together," a syllogism (or syllogistic reasoning or syllogistic logic) is a deductive system of formal logic that presents two premises (the first one called "major" and the second, "minor") that inevitably lead to a sound conclusion. MAJOR PREMISE: All men are mortal. MINOR PREMISE: Socrates is a man. CONCLUSION: Therefore, Socrates is mortal. A syllogism's conclusion is valid only if each of the two premises is valid. Syllogisms may also present the specific idea first ("Socrates") and the general second ("All men"). symbol/symbolism—generally, anything that represents itself and stands for something else. Usually a symbol is something concrete— such as an object, action, character, or scene--that represents something more abstract. However, symbols and symbolism can be much more complex. One system classifies symbols in three categories: (1) Natural symbols are objects and occurrences from nature to represent ideas commonly associated with them (dawn symbolizing hope or a new beginning, a rose symbolizing love, a tree symbolizing knowledge). (2) Conventional symbols are those that have been invested with meaning by a group (religious symbols such as a cross or Star of David; national symbols, such as a flag or an eagle; or group symbols, such as a skull and crossbones for pirates or the scales of justice for lawyers). (3) Literary symbols are sometimes also conventional in the sense that they are found in a variety of works and are generally recognized. However, a work's symbols may be more complicated as is the whale in Moby Dick and the jungle in Heart of Darkness. On the AP exam, try to determine what abstraction an object is a symbol for and to what extent it is successful in representing that abstraction. synecdoche—a figure of speech in which a part is used to represent a whole. Synecdoche is usually treated as a type of metonymy, the difference between the two being that while metonymy uses something adjacent or additional for the object implied (i.e. Oval Office for president), while synecdoche using an integral part of the whole (i.e. wheels for car). synesthesia—when one kind of sensory stimulus evokes the subjective experience of another. Ex: The sight of red ants makes you itchy. In literature, synesthesia refers to the practice of associating two or more different senses in the same image. Red Hot Chili Peppers’ song title, “Taste the Pain,” is an example. 13 APELC Glossary of Terms synthesis—the combination of two or more ideas in order to create something more complex in support of a new idea. syntax—the way an author chooses to join words into phrases, clauses, and sentences. Syntax is similar to diction, but you can differentiate them by thinking of syntax as the groups of words, while diction refers to the individual words. In the multiple-choice section, expect to be asked some questions about how an author manipulates syntax. In the essay section, you will need to analyze how syntax produces effects. tautology—the repetitive use of phrases or words which have similar meanings; it is expressing the same thing two or more times. Tautology is a type of fallacy which basically just repeats the premise. FOOTBALL FAN: The Patriots are favored to win this season since they’re the preferred team. text—while this term generally means the written word, in the humanities it has come to mean any cultural product that can be “read”— meaning not just consumed and comprehended, but investigated. This includes fiction, nonfiction, poetry, political cartoons, fine art, photography, performances, fashion, cultural trends, and much more. theme—the central idea or message of a work, the insight it offers into life. Usually theme is unstated in fictional works, but in nonfiction, the theme may be directly stated, especially in expository or argumentative writing. thesis—in expository writing, the thesis statement is the sentence or group of sentences that directly expresses the author's opinion, purpose, meaning, or position. Expository writing is usually judged by analyzing how accurately, effectively, and thoroughly a writer has proved the thesis. tone—similar to mood, tone describes the author's attitude toward his material, the audience, or both. Tone is easier to determine in spoken language than in written language. Considering how a work would sound if it were read aloud can help in identifying an author's tone. Some words describing tone are playful, serious, businesslike, sarcastic, humorous, formal, ornate, sardonic, and somber. transition—a word or phrase that links different ideas. Used especially, although not exclusively, in expository and argumentative writing, transitions effectively signal a shift from one idea to another. A few commonly used transitional words or phrases are furthermore, consequently, nevertheless, for example, in addition, likewise, similarly and on the contrary. More sophisticated writers use more subtle means of transition. trope—an artful variation from expected modes of expression of thoughts and ideas., a figure of speech involving a “turn” or change of sense—a use of the word in a sense other than its proper or literal one. Common types of tropes include: metaphor, synecdoche, metonymy, personification, hyperbole, litotes, irony, oxymoron, onomatopoeia, etc. truism—a statement that is obviously true and says nothing new or interesting. Actions speak louder than words. Don’t yell fire in a crowded theatre. understatement—the ironic minimizing of fact, understatement presents something as less significant than it is. The effect can frequently be humorous and emphatic. Understatement is the opposite of hyperbole. undertone—an attitude that may lie under the ostensible tone of the piece. Under a cheery surface, for example, a work may have threatening undertones. William Blake's "The Chimney Sweeper" from the Songs of Innocence has a grim undertone. voice—refers to two different areas of writing. One refers to the relationship between a sentence’s subject and verb (active and passive voice). The second refers to the total “sound” of a writer’s style. warrant—in the Toulmin model, the warrant expresses the assumption necessarily shared by the speaker and the audience. wit—in modern usage, intellectually amusing language that surprises and delights. A witty statement is humorous, while suggesting the speaker's verbal power in creating ingenious and perceptive remarks. Wit usually uses terse language that makes a pointed statement. Historically, wit originally meant basic understanding. Its meaning evolved to include speed of understanding, and finally (in the early seventeenth century), it grew to mean quick perception including creative fancy and a quick tongue to articulate an answer that demanded the same quick perception. zeugma—a trope, one word (usually a noun or main verb) governs two other words not related in meaning. “He carried a strobe light and the responsibility for the lives of his men.”—Tim O’Brien, The Things They Carried 14