DOC110.47 KBSusan_Szenasy_1.plain_doc

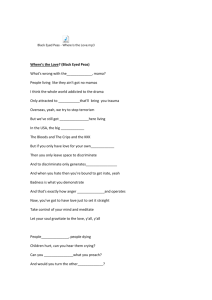

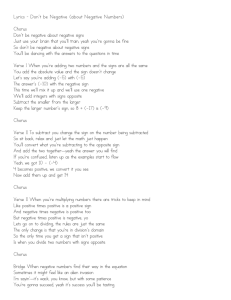

advertisement