AIS 102 American Indians and the U

advertisement

AIS 102 American Indians and the U.S. Political System - Fall 2004

Diana Ortiz

AIS 102

E-Mail: dortiz@palomar.edu or dmo77@hotmail.com

Required Texts:

Pevar, The Rights of Indians and Tribes, 3rd ed.

Canby, American Indian Law, 3rd.ed.

TIMELINE

August 22-29

Introduction and orientation; Indians/Indian Tribes

Canby: Chapter 1,

Pevar: pgs. 18-24; Chapter 15

August 30-September 5

Tribal Sovereignty/ Public Law 280

Canby Chapter 5, 8

Pevar: pgs. 122-128;

September 6-12

History and Development of Federal Policy

Canby, Chapter 2

Pevar, Chapter 1; 121-122, General Allotment Act

September 13-19

Tribal-Federal relationship; Freedom of Religion

Canby: Chapter 3, pgs. 313-324

Pevar, Chapters 3, 5

September 20-26

Modern Tribal governments - their structures and powers

Canby, Chapter 4

Pevar, Chapter 6

September 27-October 3

Tribal Gaming

Canby: Chapter 10

Pevar: Chapter 16

*October 4-17

MID-TERM

October 11-17

International Relationships; Indian Child Welfare Act; NAGPRA

Canby, pgs. 324-342

Pevar, Chapters 13, 14, 17

October 18-24

Indian lands and land claims; Native Hawaiians

Canby: Chapter 12

Pevar: pgs. 24-27

QUIZ/ASSIGNMENT: due Oct. 23

located in the quiz/exam folder

October 25-31

Treaty rights

Canby: Chapter 6

Pevar: Chapter 4

November 1-7

Hunting and fishing rights

Canby: Chapter 15

Pevar: Chapter 11

Novemebr 8-14

Water Rights

Canby: Chapter 14

Pevar: Chapter 12

November 15-21

Civil and Criminal Jurisdiction

Canby, Chapter 7

Pevar, 7, 8, 9

*November 24

Paper Due

November 29-December 5

Taxation And Regulation

Canby: Chapter 9

Pevar: Chapter 10

*December 6-17

FINAL EXAM

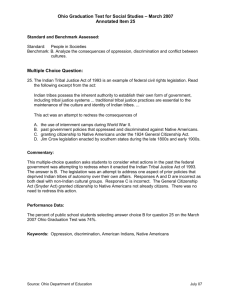

Lecture 1

American Government Review

Sources of Law

There are several sources of law in the United States:

Constitution

Statutes

Treaties

Case law – court interpretations of the law

We will be discussing all of these sources in this class.

Governmental Branches

The following is a review of the roles and functions of the three governmental branches. We will be

addressing topics this semester that involve all three branches.

The three branches of government are: Executive, Legislative and Judicial. The role of the Legislative

branch is to create law through the passage of statutes. The role of the Judiciary is to interpret law and the

role of the Executive is to implement law.

Legislature

Congress is comprised of the House of Representatives and the Senate. The House of Representatives has

435 members. The Senate has 100 members (2 from each state).

In California, the legislative branch is comprised of the Senate, with 40 members, and the Assembly, with

80 members. (As you will see during the semester, the state plays a very limited role in Indians affairs).

Executive

The President heads up the executive branch of the federal government. Beneath the President, are

numerous federal agencies, such as the EPA, Dept. of Interior and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. (The

Bureau of Indian Affairs is an agency within the Dept. of the Interior).

At the state level, the governor heads up the executive branch and also has numerous agencies beneath him.

Political Parties

Republicans hold a majority in both the Senate and the House of Representatives, and the current President

is Republican.

Does it make a difference which political party a political representative is from? Yes. The Democratic

Party generally supports taxation, regulation and social programs while Republicans support lower taxes,

particularly for corporations and the highest tax brackets, less social spending and less federal regulation. It

has been said that the Republican Party represents the wealthy. This is primarily due to their emphasis on

reduced social spending, such as subsidized housing and welfare.

When voting takes place on Capitol Hill, most politicians are expected to follow party lines. As you will

see, politics is not a pretty business, hence the old adage: there are two things that you don’t want to see

made - sausage and law. (In this class, we will not look at sausage, but we will be looking at law).

In addition, the president makes federal judicial appointments, but these must be confirmed by the Senate.

This gives the Senate power to block appointments. This is a ploy that was used by the Republican Senate

during the Clinton administration to ensure that Democratic judges were not appointed.

There is an increasing number of Indian Republicans, but since becoming U.S. citizens, Indians have been

predominantly Democrats. Why are there now more Indian Republicans? Some tribes have increasing

resources and depend less on government grants to provide governmental infrastructure. These resources

have also resulted in little or no need for welfare and similar social programs for tribal members. This has

occurred on reservations that previously suffered from severe poverty. This changes the needs of both the

tribe and the individual, and often changes their political ideology.

Creating Law

Some of you may remember the cartoon that featured a bill on the capitol steps, and sang a catchy little

tune about how laws are made. If you don’t, that’s okay, I’ll give you my version – but I’m sorry there is no

song to accompany this.

Laws start as bills and are launched by a committee that addresses that type of bill. For example, the Senate

Select Committee on Indian Affairs addresses all Indian issues in the Senate (The House Resources

Committee addresses Indian issue in the House of Representatives). A bill must be authored by at least one

legislative representative, and is often sponsored by more than one. (The ideas belong to the

representatives, but the bills are actually written by a department of the government, who do nothing but

write laws).

If the committee passes the bill, it then goes to the full legislative body. For example if the Senate Select

Committee on Indian Affairs passed a bill, it would then be heard on the floor of the Senate. If the Senate

passes it without changes, it then goes to the House of Representatives, where it once again must go to a

committee before being heard on the floor. If any changes are made to the bill while in the House of

Representatives, it must return to the Senate committee, then the Senate floor for approval of those

changes. This process can keep bills bouncing back and forth for quite some time before a statute is

actually passed, and the final version of the bill often has little in common with the original bill. Once

Congress passes a bill, it must be signed into law by the President. If the President vetoes a bill, it requires

a 2/3 vote of Congress for the bill to become law. It is therefore very difficult for a bill to become law

without the consensus of the President.

When you read a bill, you can tell where it originated by the letters preceding the bill number. If it begins

with “S” it originated in the Senate. If it begins with “HR”, it originated in the House of Representatives.

Similarly, state bills begin with “SB’ if they originated in the Senate, and “AB” if they originated in the

Assembly.

Judiciary

The role of the Judiciary is to interpret the law. Keep this in mind as the semester proceeds. At times it may

seem that the judiciary has lost sight of their role.

The federal judicial system consists of three levels. All cases are first heard in the District Court. If a party

is not happy, he or she may appeal to the Court of Appeals for the district in which the original action was

heard. There are 11 appellate judicial districts, known as circuits. In California, we are in the 9th Circuit.

Any decisions made by the 9th Circuit are only valid law in our region. There are many times when

different circuits come up with conflicting opinions, and therefore, conflicting law.

If a party is unhappy at the appellate level, they can apply to have the case heard by the U.S. Supreme

Court by filing what is know as a petition for certiorari. (There may be footnotes or citations to cases

throughout the semester that read “cert. denied”. This means that the Supreme court refused to hear the

case). The petition is simply a request for the Supreme Court to hear the case. The U.S. Supreme Court is

under no obligation to hear cases, and takes only those cases that they want to hear. They hear only cases

involving areas of federal law (as opposed to state law). They are suppose to take all cases in which there is

a conflict among the appellate courts, but this doesn’t always happen. (The current Supreme Court has

taken fewer cases than any court in history).

The judiciary is not considered a political body, but remember the President appoints Supreme Court

justices and the appointments are ratified by the Senate. Presidents tend to select justices that have similar

political views. Once appointed, the justices serve for life, or retirement whichever comes first. Thus, the

President’s political views can carry over into the courts long after he has left office.

Many of the current justices were appointed by conservative Presidents. We therefore have a conservative

court, which supports state’s rights and has not been particularly kind to Indian interests. (A recent study

indicated that the current U.S. Supreme Court upholds criminal rights more often than it upholds tribal

rights).

Political Power

What does it take to have political power? Money. Political campaigns are very expensive, and most

candidates are in need of funds. It is illegal to offer a large campaign contribution (or a small contribution)

in exchange for a vote on a specific issue. It is not illegal, however, to offer a campaign contribution and at

some later time, ask for a vote on a specific issue. The end result is that money buys political power so

gaming tribes are often politically powerful.

Keep these concepts in mind as we move forward throughout the semester.

TRIBAL SOVEREIGNTY

What is an Indian Tribe?

A tribe is a group of Indians recognized as constituting a distinct and historically continuous political entity

for at least some governmental purposes. There are both federally-recognized and non-recognized tribes.

Federal recognition allows tribes to build a governmental infrastructure and entitles tribes to federal grants

for medical services, housing, etc., but not all federally-recognized tribes have land. You will see when we

discuss termination, that in the 1950s many tribes lost their land and still remain landless.

Federal recognition may arise from a treaty, statute, executive order, administrative order, or from a course

of dealing with the tribe as a political entity. The BIA determines which tribes will be recognized, but it

was not until 1978 that they promulgated a set of rules setting forth the requirements for recognition. Prior

to 1978, this was done on a case by case basis. Since then, bills have been introduced in Congress, at

various times, which would take this task from the BIA and give it to an independent commission

appointed by the President. Congress has thus far not passed any such bill and it still remains within the

domain of the BIA.

Among the requirements for recognition are that:

1. The tribe must have a government that exercises power over its members; and

2. The tribal government continued to function as an autonomous entity throughout history until the

present; and

3. The tribe has been identified as an American Indian entity on a substantially continuous basis since 1900

(This can be demonstrated by using books, magazines, anthropologists, historians, etc.); and

4. The tribe occupies a specified territory or inhabits a community viewed as distinctly Indian.

If the BIA does not follow their own criteria, a tribe seeking recognition can appeal to an administrative

board, then to federal court. There is no right to contest the criteria for recognition – only the application of

the criteria to a particular tribe.

Example: (The following example is completely fictitious and is used for demonstrative purposes only).

The First People’s Tribe was a federally-recognized tribe in Orange County. In 1950, Orange County began

to flourish and the tribe began to intermarry. By 1960, there was little interest in tribal affairs. The

reservation was leased to Disneyland and the tribal members disbursed throughout the community. In 2000,

Proposition 1a was passed, which allows Indian tribes to have casinos. Descendants of the First People’s

Tribe now want to re-establish their tribal government and open a casino. Should the tribe still be federally

recognized?

No, the tribe would no longer have federal recognition. Once a tribe receives recognition, it can lose

recognition only by:

1. Voluntarily ceasing to function as a government; or

2. Congress can decide to no longer recognize the tribe.

In the example, the tribe ceased to function as a government, so they are no longer entitled to federal

recognition.

There are a few cases in New England where a state recognized a tribe but the federal government did not.

The states recognized tribes, took their land and gave tribes reservations and financial assistance as a

reward for siding with colonists in 1776. Some tries later petitioned for, and some have received, federal

recognition.

There have been many cases where the federal government has placed more than one tribe on a single

reservation and recognized this new tribe by another name. For example, the Blackfeet Tribe is comprised

of the Blackfoot, Bloods and Piegans – three distinct tribes. Their northern counterparts remain separate

tribes in Canada.

Who is an Indian?

Many of you are of mixed ancestry. Do you know exactly what fraction of ancestry you have from each

nationality? Most Indians know exactly how much “Indian blood” they have because it is required for

various purposes.

The textbooks discuss four definitions of “Indian”.

1. Tribal requirements

2. Federal jurisdiction

3. General meaning

4. Census Definition

Tribal Definition

Tribal enrollment is specifically within the jurisdiction of the tribe itself. Blood quantum required for tribal

enrollment varies from tribe to tribe. Some tribes, such as the Cherokee, have no blood quantum

requirement while others, such as the Mississippi Choctaw require that members have ¾ Indian blood

quantum. Other tribes have recently introduced a requirement that an individual must live on the

reservation to become enrolled.

When there is no blood quantum requirement, an applicant for enrollment must be able to trace their

ancestry to a tribal member, and in some cases the applicant’s mother or father had to be an enrolled

member of the tribe.

A tribe can change its requirements for enrollment at any time that it chooses. For example, Santa Clara

Pueblo required that the mother be an enrolled member of the Pueblo for her children to be enrolled. The

tribe later changed the requirement so the father had to be an enrolled member. Mrs. Martinez had a child

and attempted to enroll her child. The child had the requisite blood quantum, but since the father was not an

enrolled member, the child was ineligible for enrollment. (Mrs. Martinez sued the tribe in federal court in

an attempt to get her child enrolled, but she lost).

Federal Definition

To receive government services, in many cases, but not all, there is a requirement of ¼ Indian blood from a

federally-recognized tribe. The federal government does not consider members of non-federally-recognized

tribes to be Indians. As we will discuss in more detail later, in the 1950s, Congress terminated many tribes.

When the tribes were terminated, that is, no longer federally-recognized, the individual tribal members

were no longer considered Indians by the federal government, and were no longer eligible for federal

services.

Enrollment does not always determine jurisdiction. Often eligibility for enrollment is enough to consider an

individual a “member” of a federally recognized tribe for purposes of application of federal law.

General Definition

If you have 1/252 degree of Indian blood, does this make you an Indian under the general definition?

The general definition of an Indian is that:

1. The individual must have some degree of Indian blood; and

2. The individual must be recognized as an Indian by the relevant community.

In my example, you have met part one of the test because you have some Indian blood. Part two depends

on how the community recognizes you. If you are enrolled in a tribe with no blood quantum requirements,

you have clearly fulfilled the second part of the test. If you are not enrolled in a tribe, it may be a harder

matter to prove and your success may depend on the purpose for which you are using the identification.

One question for you to ponder is this: “Indian blood” defines who is and is not an Indian so if an

individual is ¼ Indian and receives a blood transfusion from a non-Indian, is he still ¼ Indian?

Census Definition

Does the census definition accurately reflect who is or is not an Indian?

The census considers anyone to be an Indian who claims to be an Indian. This often results in large

discrepancies between the other definitions of an Indian and the census definition. Indians living on the

reservation often do not respond to census requests, while other individuals who have some Indian blood,

but are not enrolled in a tribe, may report themselves as an Indian to census takers. For example, the 1990

census reports that the Blackfeet tribe has 32,234 members, while the tribe reports approximately 14,500

for the same period.

Indian Country

Indian Country will become more relevant later in the semester as we talk about Indian land holdings and

jurisdiction.

Lecture 2

Tribal Sovereignty/P. L. 280

History of Tribal Sovereignty

Sovereignty is defined as the inherent right to self-govern. It is sovereignty that sets Indians apart from

other minority groups, and it is sacred among Indians.

A dichotomy existed from the time of the initial contact with Europeans. European powers believed in the

discovery doctrine. They believed they had rights to the whole world, even those areas inhabited by

indigenous peoples, subject only to an earlier European claim, because only European Christians could own

land. At the same time colonial powers, and later the federal government, dealt with the Indians through the

use of treaties – agreements between sovereign powers.

The first treaty recorded between English colonists and North American Indian confederacy is the 1608

treaty between the Jamestown colony and the Indian emperor, Powhatan. From this early point in the

relations between Indian tribes and European colonists, one can see that treaty relations involved a process

of cultural as well as diplomatic negotiation. In these early treaties, the scope of ill-defined concepts, such

as tribal sovereignty, and novel institutions, such as reservations, were first tested and practiced. Much of

the theory and practices of our modern federal Indian law is generated out of this early treaty-making era.

A law was passed in 1790 known as the Trade and Nonintercourse Act aka Trade and Intercourse Act. (The

law has nothing to do with sex). This law states that Indians cannot transfer land except to the federal

government. Two colonists (land speculators), by the name of Johnson and MacIntosh each received title to

land. One received title from the federal government and the other received an earlier title from a tribal

chief. To complicate the matter, the title from the tribal chief had been given before the American

Revolution, so England was still in charge of land transfers. In 1823, the two took the case to the Supreme

Court. The court said that Indians have not completely lost their land rights, what they have is the right to

occupy the land. When they cease to occupy the land, their rights to the land are extinguished. (How would

this affect a tribe, such as those in the plains, that subsisted by following the buffalo? A prediction would

be that if they leave the land, their rights cease at that point).

In 1831 and 1832, two other cases were decided by the court. (These cases and that discussed above have

become known as the Marshall trilogy, because they are three landmark decisions authored by Chief Justice

Marshall). In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, the Cherokee Nation argued that it was a foreign nation. Even

though Cherokee Nation v. Georgia was not decided by the Supreme Court due to lack of jurisdicition, it

remains a pivotal case in federal Indian law. The Court conncluded that Indian tribes are not foreign , at

least as that term is used in the U.S. Constitution, in describing the Court's original jurisdiction over

controversies between a state (Georgia) and foreign states (tribes). Rather, Justice Marshall's opinion for

the Court holds that tribes are "domestic dependent nations," whose relations with the U.S. resemble that of

a "ward to his guardian." This language gives birth to the "Trust Doctrine" in federal Indian law. This

fundamental doctrine governing the federal-tribal relationship holds that the U.S. has a trust responsibility

to act on behalf of Indian tribes.

The last of the Marshall trilogy, Worcester v. Georgia, involved several missionaries attempting to

Christianize the Indians. Georgia passed a law that required any non-Indians entering Indian Country

within the state to receive a permit from the state of Georgia. The missionaries had no such permit. At the

request of the tribe, the missionaries refused to get a permit, to allow the Supreme Court to decide if the

tribe was on equal footing with the state. As the case wore on, and the missionaries were sentenced to

perform hard labor for their crimes, several of the missionaries cooperated with the state. By the time the

case was decided there were only two missionaries who faced a sentence of hard labor. The U.S. Supreme

Court accepted the case and decided that tribes are on equal footing with the state and that state laws have

no force and effect in Indian Country.

The court’s decision in Worcester v. Georgia has been diluted over the years. In a 1973 case, McClanahan

v. Arizona Tax Commission, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that state law can intrude into Indian country

only if two conditions are met:

1. There is no interference with tribal self-government and

2. Non-Indians are involved.

Tribal Jurisdiction Over Non-Indians

Canby speaks of the “Montana Rule” which applies when looking at tribal powers over non-Indians. Tribes

have power to regulate non-Indian conduct, on non-Indian land within reservation boundaries, if

1. The non-Indian enters into consensual relationships with the tribe or its members; or

2. The conduct threatens or directly affects the tribe’s political integrity, economic security, or the health or

welfare of the tribe.

For example, if the telephone company provides telephone service on the reservation, they must comply

with tribal law, even if the service is provided to a non-Indian on his own land, if his land is within the

exterior boundaries of an Indian reservation. (As a practical matter, if tribal law is too restrictive, the

telephone company may choose not to conduct business on the reservation).

Congressional Power Over Tribal Sovereignty

Congress has what is known as plenary power over Indian affairs. (This means plenty of power). The U. S.

Constitution is the source of Congressional power and serves as its only restraint, subject to interpretation

by the courts.

Article I, Section 8, of the U.S. Constitution is known as the “Indian Commerce Clause” and states that

“The Congress shall have the power…to regulate commerce with the foreign nations, and among the

several states, and with the Indian tribes.”

In the late 1800s, Congress passed a law known as the Major Crimes Act, which gave the federal court

jurisdiction over Indian vs. Indian crimes, which it did not previously have. This law was challenged in

1886, in U.S. v. Kagama. Kagama was a member of the Hoopa tribe in Northern California. He was tried

for murder under the Major Crimes Act. He challenged Congress’ power to pass the act, claiming that it

had nothing to do with the regulation of trade. The United States made an interesting argument in this case.

They argued that if the federal government did not have the authority to punish murderers of Indians, even

other Indians, then there would be less trade to regulate. The court did not buy this argument, but they did

decide that the federal government had the power to pass the law, because if the federal government didn’t

have this power then only the tribes would have the power to punish murder of one Indian by another

Indian. (And it certainly couldn’t be left in the hands of Indians to punish their own tribal members).

This case and an additional case, Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, set the limits on Congressional power over

Indian affairs. Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock involved an 1867 treaty with the Kiowas and Comanches known as

the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek. Terms of the treaty stated that it could only be amended by a vote of

¾ of the adult Indian males occupying the land set aside for the tribes. Prior to the treaty, the tribes had

sustained themselves by hunting buffalo. When placed on a reservation, they were forced to rely on

government rations, which were insufficient, so the Indians were starving. At the same time, there was an

influx of non-Indian settlers, which created a demand for more land. The Cherokee Commission, an entity

created by the executive branch of the federal government, attempted to renegotiate the treaty to obtain an

additional 2,150,000 acres of land from the tribes.

The government agents acquired the signatures of 456 adult males. They certified that there were 562

eligible voters, thus giving them the assent they needed to modify the treaty. A tribal roll prepared less than

three months after the Commission certification showed that there were 725 adult males over the age of 18

and 639 over the age of 21, so the Commission did not have enough votes to amend the treaty.

Since fraud was committed, should the treaty amendment be valid?

The tribes sent a letter repudiating the signatures and spoke to the President, but the treaty amendment was

sent to Congress for ratification. Congress investigated the matter and both the Secretary of the Interior and

the Indian Affairs Commissioner asked Congress not to ratify the agreement. Congress then attached

ratification of the agreement as a rider to another bill, and passed the bill.

The tribes sued to stop enforcement of the agreement. The court said that congressional power is a political

power not subject to judicial control. Since Congress has the power to eliminate treaties entirely, they must

presume that Congress acted in good faith. The court further reasoned that if Congress were to be

controlled, it would eliminate their ability to act in case of emergency.

These decisions have given Congress virtually unfettered power over Indian affairs. The only area in which

the courts have restrained Congress is when land is taken without providing any compensation.

Sovereign Immunity

If you are at a tribal casino and the roof falls in on you, and breaks your back can you sue?

All sovereign powers have what is known as sovereign immunity. The doctrine of sovereign immunity

states that you cannot sue a sovereign without its consent. The federal government has what is known as the

Federal Tort Claims Act that sets out the procedures and circumstances under which the federal

government will accept liability for injuries on federal land. The state has a similar ordinance. In the case of

Indian tribes, consent to suit can come from either Congress or the tribe. In the example above, you cannot

sue for your injuries, unless the tribe allows you to sue. (In California, all gaming tribes must have what is

known as a Tort Claims Ordinance, which says if you can sue, and procedures for doing so).

Assume in the example above, that the tribe has not waived its sovereign immunity. This infuriates you so

you walk out of the tribal casino with a slot machine, valued at $10,000. The tribe sues you to recover their

slot machine, so you sue them for your injuries that have resulted in $100,000 in medical bills. Can you do

this?

There is a doctrine known as recoupment. Recoupment says that if a sovereign, in this case a tribe, sues

you, the tribe’s sovereign immunity is waived only to the extent that they sued you. So in my example, you

could only sue the tribe for $10,000 – the amount for which they sued you. If it was an old used slot

machine, and they only sued you for $500, you could only counterclaim against the tribe for $500.

P.L. 280

In 1953, during what is known as the termination era, Congress passed a law known as Public Law 83-280.

The purpose of P.L. 280 was to relieve the problem of lawlessness on California reservations.

There were problems with P.L. 280 from the beginning because the federal government did not appropriate

any money to repay the states for the services they were mandated to provide. At the same time, tribes

resented the intrusion into their sovereignty.

P.L. 280 gave 5 states extensive criminal and civil jurisdiction over Indian Country. Alaska was added later

which now makes six states where Congress imposed P.L. 280 jurisdiction without state or tribal consent.

These are known as the “mandatory states.” P.L. 280 was amended in 1968 so that both tribes and the state

must consent to state jurisdiction, but this only affects the imposition of state jurisdiction under P.L after

1968. The mandatory states were unaffected by this amendment. There is also a provision for retrocession –

which is returning jurisdiction from the state to the tribes. The problem with retrocession is that the state

must request that the federal government grant jurisdiction back to the tribes – the request does not come

from the tribe itself.

Civil Jurisdiction

Courts have diluted the grant of civil jurisdiction under P.L. 280. If you read the act literally it seems to

have few limits on state jurisdiction, but Courts have stated that Congress seems to have added the civil

portion of P.L. 280 as an afterthought. This is due to the lack of legislative history attached to the bill, as

there usually is. Since there is no legislative history, the courts have interpreted the act as they see fit.

As Canby indicates, county and local ordinances do not apply on Indian reservations. Does this mean there

is no building code on Indian reservations? Yes, building codes are county law. Unless the tribe adopts a

building code, there is no building code applicable to Indian reservations. (Under the current gaming

compact, a code must be adopted for casino construction).

If suit is brought in state court against an individual Indian, state law will apply, but tribal ordinances and

customs have full force and effect if they are not inconsistent with state laws.

Lecture 3

Federal Policy

There are 2 basic views regarding Indian tribes:

1. Indian tribes are here to stay and need a land base which needs to be protected.

2. Tribes should disappear and their members absorbed into mainstream society.

The result is that for the last two hundred and twenty-five years federal policy regarding Indian affairs has

been pendulum-like, swinging back and forth between assimilation and self-determination. This shift does

not occur instantly, it rather resembles a continuum:

Assimilation____________________________________________Self-determination

The textbooks divide the history of federal Indian policy into several eras.

1. Colonial Period – ended in 1820

Initially, European powers dealt with Indians through the use of treaties. After the American Revolution,

the federal government continued this practice for two reasons: Non-Indian settlers needed land, and war

weary from the American Revolution, the federal government wanted to ensure peaceful relations with

Indians.

European powers, and later the federal government, took the role of a protector of the Indians from the

settlers who wanted land. The U.S. Constitution gave Congress power over Indian affairs, so Congress

passed a series of Trade and Intercourse Acts that made interactions with Indians subject to federal control.

2. Removal (1820-1850)

Generally, the non-Indian community believed that Indians would assimilate, become christianized and live

in the European tradition. There were those, however, including Thomas Jefferson and his followers, who

didn’t believe Indians and non-Indians could live together. Jefferson therefore urged voluntary removal of

Indians to their own territory west of the Mississippi River.

Indians were moved from the southeast U.S. to Oklahoma, many of them dying along the way. This

resulted in what has become known as the “trail of tears.” The move was termed “voluntary”, but under the

circumstances, tribes were left with little choice other than to leave their homelands. By 1849, the eastern

U.S. was almost entirely free of Indian tribes. The Bureau of Indian Affairs was then moved from the War

Dept. to the Dept. of Interior.

3. Movement to Reservations (1850-1887)

Non-Indians began to move westward. The federal government created a policy of restricting tribes to

reservations. Tribes were moved entirely or were granted portions of their land, with the bulk of the land

going to the federal government through treaties that were often coerced or fraudulently induced.

When Indians were placed on reservations, Indian agents supervised their adaptation of non-Indian ways.

Organized religions tried to christianize Indians and reservations were divided among the churches. There

are many Baptist churches on reservations; however in the west, Catholic churches are dominant. Some

traditional religious dances and ceremonies were outlawed at this time, to encourage christianization of the

Indians.

One of the most significant events of this era, in a legal sense, occurred in 1883. The U.S. Supreme Court

issued an opinion in a case known as Ex Parte Crow Dog. Crow Dog killed Spotted Tail on the Lower

Brule Sioux Reservation. Both Crow Dog and Spotted Tail were members of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe.

The district court in the Dakota territory sentenced Crow Dog to death for the murder of Spotted Tail. Crow

Dog claimed that the laws of the U.S. did not apply and that the district court had no jurisdiction to try him.

He then applied to the Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus. (This is a request that is made when an

individual is being illegally held against his will).

There was a law that applied in Indian Country which stated that general laws of the United States applied

to punish crimes committed anywhere in the exclusive jurisdiction of the U.S., including Indian Country.

The act provided for an exception when an Indian had been punished by the local law of the tribe, or in any

case when a treaty provision gave the tribe exclusive jurisdiction over such offenses.

The argument made in support of jurisdiction was that pursuant to a treaty, the U.S. had jurisdiction. The

treaty provided that “If bad men among the Indians shall commit a wrong or depredation upon the person

or property of any one, white, black, or Indian, subject to the authority of the Untied States,” the Indians

will turn them over to the United States to be punished. The court said it is clear that this was not meant to

apply to a crime committed by an Indian against another Indian.

Next, the U.S. relied on treaty language that said, “Congress shall, by appropriate legislation, secure to the

tribe “an orderly government.” The court said this meant self-government - the tribe could maintain peace

and order through use of their own laws and customs. The court further said that Indians should be judged

by their own law not by “one which measures the red man’s revenge by the maxims of the white man’s

morality.” (In this case, peacemakers of the tribe negotiated with the families of Spotted Tail and Crow

Dog for compensation for Spotted Tail’s death. Crow Dog and his family gave Spotted Tail’s family $600,

eight horses and one blanket to compensate them for the loss of Spotted Tail).

It is said that by the time the court’s decision reached the Dakota Territory, Crow Dog had a noose around

his neck. Non-Indian authorities had no choice but to let him go.

The BIA had been lobbying Congress for many years to get federal criminal jurisdiction extended into

Indian Country. Congress reacted to this case by giving the BIA what they wanted. The Major Crimes Act

was passed, which granted criminal jurisdiction over certain crimes to the federal government. This marked

the beginning of the next shift in federal policy towards assimilation.

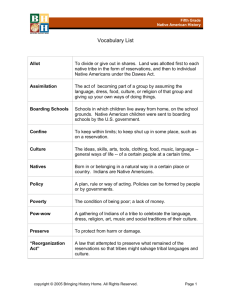

3. Allotment and Assimilation (1887-1928)

Those friendly to Indians realized that there was hopeless poverty on reservations. Other non-Indians

resented the reservation system because there were tracts of land that were completely unavailable to

settlers.

In 1887, the General Allotment Act, also known as the Dawes Act, was passed. Under the plan, Congress

thought they could assimilate the Indians in a single generation. It was supported by those sympathetic to

the plight of Indians, who believed that Indians could be given plots of land, become middle-class farmers

and assimilate into mainstream society.

The Act authorized the President, whenever he believed it was advantageous to the Indians, to allot

reservations into farm-size parcels, according to a formula dictated by Congress. The act called for 160

acres of land to be given to the head of each family. 80 acres was to be given to all other tribal members.

These quantities were doubled if land was only suitable for grazing, but later all quantities of land to be

distributed were cut in half.

There were many problems with the Allotment Act, as you will see from the external links. One of the

problems with allotments is that it didn’t provide for future generations. The land was divided at a specific

point in time among those who were alive at that time.

The Allotment Act provided that allotments were to be held in trust by the federal government for 25 years.

This meant that the federal government owned the land for the benefit of the individual tribal member. The

purpose of the 25-year period was to give Indians time to learn proper farming and business methods.

During this period, the land was not subject to state law including taxation, but at the end of the 25-year

period, title to the land was given to the individual Indian and state law applied, including taxation. Many

allottees lost their land because they could not pay the taxes.

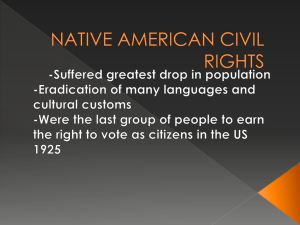

Indians living on reservations were not considered U.S. citizens until 1924; however, under the Allotment

Act, upon receiving an allotment, an Indian became a U.S. citizen and was subject to state criminal and

civil law. In 1906 the Allotment Act was amended so that Indians became citizens when the trust period

expired and they received title to their land.

Each reservation had a federally appointed Indian agent. The agents withheld rations and annuities for

individuals who wouldn’t work their land. For many tribes, agriculture was not a natural way of

subsistence. Plains Indians were hunters, traditionally following the buffalo. Indians in Washington and the

Great Lakes were fishermen. Even the withholding of food and money was insufficient to convert many

Indians to a life of farming.

In 1891, the Allotment Act was amended to allow the Secretary of the Interior to lease the land of any

allottee who couldn’t benefit from or improve his allotment. If the agent didn’t like the way an allotment

was being used, he could lease it to whomever he wanted. After 1891, leasing became a common

occurrence.

A further problem is that the Allotment Act subjected allotted land to state intestacy laws if the allottee died

without a will. Most Indians didn’t have wills. Under state law, if a person dies without a will, the property

will pass to his or her spouse. If there is no spouse, the property passes to his or her children. In the 1800s,

it was common to have large families. If an Indian died without a spouse, each child would receive an

undivided interest in the parent’s property. For example, if a man dies leaving 10 children, each child will

receive a 1/10th share of the allotment. If each of those children has 10 children and dies without a will,

those children will inherit a 1/100th interest in the land. These interests are undivided. That is, each of the

100 people doesn’t get an acre of land; they all receive a 1/100 th interest in the entire parcel. To do anything

with the land, there must be agreement of all 100 owners. Getting 100 family members to agree on

anything is a tumultuous task (at least in my family). This has resulted in many allotments being unused.

This problem still exists today.

By the mid-1920s, the federal government realized that assimilation was not going to work and the shift

began towards reorganization.

4. Reorganization (1934 - 1953)

The Merriam Report was prepared at the direction of the Secretary of the Interior to assess conditions on

Indian reservations. The report stated that the Congressional purpose behind the Allotment Act was to

make farmers out of the Indians, but the act provided for instruction and training in agriculture, which did

not occur. The report further outlined procedures for improving Indian services and made recommendations

for expenditures of funds.

Congress was outraged when they received the Merriam Report. The general belief was that the report was

slanted in favor of the bureaucratic apparatus of the BIA. The Senate Committee on Indian Affairs

therefore conducted their own investigation. Several years later, after the senators made many trips to

reservations and observed the poverty firsthand, they came up with basically the same results.

In 1934, the Indian Reorganization Act, (IRA), also known as the Wheeler-Howard Act, was passed to

rectify conditions on the reservations. The Act promised expanded social programs, federal funding of

projects and put an end to allotments. It also extended the trust period indefinitely for existing allotments

that were still in trust. In addition, it authorized the Secretary of the Interior to restore to tribal ownership

any excess lands the federal government acquired from the tribes under the Allotment Act, as long as the

land was still held by the government.

The IRA allowed tribes to organize for their common welfare and adopt a constitution and bylaws to be

approved by the Secretary of the Interior. The BIA sent a model constitution and bylaws to all tribes. The

constitution and bylaws had to be approved by the majority of adult Indians residing on the reservation

within two years. Benefits to tribes if they organized pursuant to the IRA were that, the tribe had the right

to:

1. Employ legal counsel, subject to BIA approval

2. Prevent the sale, disposition, lease or encumbrance of lands or other tribal assets without their consent

3. Negotiate with federal, local and state governments

4. Receive appropriations

5. Form Tribal Corporations

181 tribes voted to accept the act and 77 tribes specifically rejected the act, including the Navajo tribe.

Tribal governments were bolstered under the IRA, but not in the traditional sense. The new governments,

created at the direction of the BIA, often had little resemblance to the tribal governments that once existed,

but even using this federal model, this era of supporting tribal governments only lasted until 1953.

Termination and Relocation (1953 - 1961)

This period began towards the end of World War II. Domestic budgets were reduced to support the war

effort and many federal agencies were reduced or closed. Many Indians left the reservation to work in

factories or join the armed forces. The federal government began a policy of paying Indians to leave

reservations and move to selected cities to support the war effort. In California, Los Angeles and Oakland

were selected as cities for relocation.

In 1948, Congress wanted to transfer responsibility for Indians to the states as soon as possible. At the same

time, the National Council of Churches issued a report recommending that Indians be given full citizenship

by eliminating a lot of the legislation that bound them to the federal government. Conservatives wanted

federal budget cuts and believed that Indians could make it on their own once freed from government

control, while liberals took a civil rights position and thought they could help the Indians by lifting

discriminatory legislation.

In 1947, the Senate Civil Service Committee asked the acting Indian Commissioner to bring them a list of

tribes that could function on their own, and concentrate on those that could do so within a reasonable time.

Tribes chosen for termination were based on four factors: (1) degree of assimilation of the tribe; (2)

economic conditions and available resources; (3) willingness of the tribe to dispense with federal services;

and (4) willingness and ability of the states to provide public services. In 1948, under pressure from

Congress, the BIA began to assemble this data on all federally-recognized tribes.

In 1952, House Resolution 108 was passed declaring that “at the earliest possible time, all of the Indian

tribes and the individual members thereof located within the States of California, Florida, New York and

Texas, should be freed from federal supervision and control...” ( Resolutions are statements of policy only

and have no legal effect). After receiving reports from the BIA regarding the social and economic status of

tribes, Congress passed a series of acts terminating tribes. These included the California Rancheria Act that

terminated 31 California tribes. After passage of the acts, the BIA was given a period of time to implement

complete termination of federal services to the tribes. The shortest period of time allowed was less than 1

year and the longest was 12 years.

The overwhelming majority of Indians were opposed to termination, but in San Diego County there was a

division among Indians as to whether tribes should support termination. The Mission Indian Federation, an

Indian organization that had been around for many years, was now led by Purl Willis, a non-Indian. Willis

argued in favor of termination. The argument made was that many Indians were now living off-reservation,

and yet services were provided as if all Indians still lived on reservations. Willis argued that termination

would free the Indians. It was time for them to be treated like all citizens. At the same time, a few Indians,

including Max Mazetti from Rincon, led the local opposition to termination. The argument for the

opposition was that Indians were not prepared to submit to state jurisdiction, including state taxes and

property taxes. The fear was that many Indians would lose their land if they were forced to pay taxes.

The primary argument in favor of termination in San Diego County was an economic one. All federal

health services for California Indians ended in 1955. The closest Indian hospital in San Diego County was

Soboba Indian Hospital in Hemet. This hospital was closed and many Indians tried to use the county

hospital but were denied treatment. The federal government also stopped federal support for individual

Indians with the expectation that county and state governments would carry on this function. San Diego

County refused to pay welfare benefits to Indians living on reservations until a lawsuit was filed and

decided in favor of the Indians. This lack of benefits left many Indians with no way of supporting

themselves. It was in this climate that P.L. 280 was passed.

In 1958, the Secretary of the Interior casually announced that no other tribes would be terminated without

their consent, but it was not until 1970, that the termination policy was formally repudiated. At that time, it

was President Nixon who asked Congress to officially repeal the termination policy.

Tribal Self- Determination (1968)

There was plenty of social change in the 1960s. It was the time of the Viet Nam War, the peace movement,

free love and the occupation of Alcatraz by Indians. Suddenly, it was cool to be Indian.

This era was marked by a reversal of Federal Indian policy. The new goal was to strengthen tribal

governments and once again try to make them self-sufficient. Farming failed, BIA domination through the

Indian Reorganization Act failed, total assimilation through termination failed and now the federal

government was ready to try something new.

In 1968, the Indian Civil Rights Act was passed which purported to provide individuals with protections

not previously afforded to them. The Bill of Rights serves to restrain state and federal governments but

does not apply to tribal governments since they predate the Constitution. The Indian Civil Right Act

provides for most of the rights asserted under the Bill of Rights, but not all of them.

The Indian Civil Rights Act includes a provision that requires consent from both tribes and states before

asserting jurisdiction pursuant to P.L. 280. The Act also includes a provision which provides for the

retrocession of P.L. 280 jurisdiction at the request of the state – not the tribe - so if a tribe wants to retain

jurisdiction over its own criminal and/or civil actions, it must have state approval.

In 1975, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act was passed. The act took control of

federal programs from the BIA and gave it to the tribes. At the request of tribes, the Secretary of the

Interior was directed to enter into contracts with tribes, and organizations designated by tribes, for the

administration of health, education and construction programs. The act also gave preference for American

Indians when hiring for contracts affecting Indians.

In 1982, the Indian Tribal Government Tax Status Act was passed. This act gives tribes many tax

advantages that are given to states, including the right to issue tax-exempt bonds to finance government

projects.

In 1983, President Reagan reaffirmed the policy of strengthening tribal governments, with the additional

goal of reducing their economic dependence on the federal government.

Current Policy

As you previously read, federal policy shifts between self-determination and assimilation. There are several

factors occurring in recent years that seem to indicate that the tide is shifting yet again.

The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act represents an intrusion on tribal sovereignty previously seen only in

laws affecting the sale of alcohol on reservations. Gaming compacts negotiated between tribes and states

contain varying degrees of applicability of state laws, but all compacts apply some measure of state law to

Indian tribes that did not previously exist.

The BIA’s budget has been drastically reduced since about 1995. In addition, several bills have been

proposed in the last few years that erode tribal sovereignty.

There is a bill that has been raised in at least two congressional sessions that would impose corporate

income tax on tribal governments for casino income. This is unprecedented. State, city, county and tribal

governments have never paid income tax on their earnings. The state of California pays no federal taxes on

their lottery income, yet this bill would impose such a tax on tribes. The bill has been defeated every time it

has been proposed, but it is almost certain to be raised again.

A bill has also been proposed a few times to use means testing in determining federal allocations to tribes.

This would take into account a tribe’s income from all economic development in determining how much

federal aid to give the tribe. Proponents claim that tribes, particularly wealthy gaming tribes, should not

receive appropriations from the federal government because they do not need the money. Opponents claim

that the federal government has a trust responsibility to the tribes, as enunciated in the Marshall trilogy,

regardless of income. This is the price the federal government should pay for taking tribal lands. Some fear

that means testing is the beginning of termination. This bill has also been defeated every time it has been

proposed but is sure to be raised again.

Yet another bill which has been proposed several times is Slade Gorton’s bill to eliminate tribal sovereign

immunity. This bill has thus far not passed, and Gorton was not re-elected to the senate in 2000, so it is

uncertain if this bill will be raised again. The U.S. Supreme Court has included in its opinions an invitation

to Congress to eliminate tribal sovereign immunity.

Indian housing has taken a new turn. Prior to 1994, Indians were unable to obtain mortgages on

reservations because they do not own the land. There is now a program in place, known as HUD Section

184 loans, which enable Indians to obtain federally-guaranteed mortgages to build, buy or renovate houses

on the reservation. Traditional Indian housing programs have also changed. The Dept. of Housing and

Urban Development (HUD) funds Indian housing authorities and builds houses for low-income individuals

to either buy or rent. Up until the last few years, these housing authorities have been subsidized. Low

income housing on reservations is still subsidized but the new housing laws require that Indian housing

authorities act as businesses. At the same time, it allows tribal housing authorities more flexibility by

allowing them to determine how they will allocate federal monies.

The Republican-controlled congress has had a policy of federal de-regulation and granting power to the

states. At the same time, there is a conservative U.S. Supreme Court who are consistently affirming and

expanding state rights, while limiting tribal rights.

While many Indians still live in poverty on isolated reservations, others are sophisticated, have money and

know how to use it for political gain. Some tribes, as well as individual Indians, are in a position to make

sizable campaign contributions, which equates to political power. Tribes have more political power now

than ever before in history. With the power of the tribes pitted against the conservative congress and court,

it will be interesting to see where federal policy goes in the future.

Lecture 4

Federal – Tribal Relationship/Freedom of Religion

Federal Trust Responsibility

The federal government has what is known as a “trust responsibility” to Indian tribes. This trust

responsibility was first enunciated in 1831 by Chief Justice Marshall in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia when

the court said that Indian tribes are domestic dependent nations, and that the relationship of tribes to the

federal government is that of a ward to its guardian. (It has turned out to be an abusive guardian).

This doctrine further evolved in 1886 in U.S. v. Kagama, when the court said, “Indians are the wards of the

nation… communities dependent on the United States for their daily food…” When Indians were placed on

reservations, their means of subsistence was disrupted, and in many cases completely eliminated. The

Plains Indians followed the buffalo, but when placed on reservations, they could no longer hunt for

subsistence. This did indeed make Indians dependent on the federal government for food.

As a result of this history of dealing with tribes, the duty owed to tribes by the federal government is known

as a fiduciary duty. This duty arises when the federal government has taken over control of tribal assets

such as money, land, timber, etc. This is the highest level of responsibility that can be owed to another and

means that the federal government must act within the best interests of the tribes. For example, if you

invest money in a mutual fund, the manager of that mutual fund owes a duty to use the utmost care in

managing the fund. In the case of tribes, if the federal government has control over tribal assets they are

like the mutual fund manager, they must use the utmost care in managing the tribe’s assets. Does this

always happen? No. As you will see from the external links, the BIA has grossly mismanaged tribal assets.

The federal government’s trust responsibility arises from statutes, treaties, agreements, executive orders

and the government’s historical relations with tribes. This means that the federal government has a duty to

protect federally-recognized tribes, but the federal government cannot be required to do a specific act

unless a treaty, statute, agreement, executive order or course of dealing clearly imposes or implies the

obligation. For example, courts have made the federal government litigate to protect tribal lands and

resources since management of tribal land and resources is under the control of the BIA. There was also a

case where the BIA was held liable for funds that were supposed to be paid to tribal members and were

instead paid to a tribal government that BIA officials knew were misappropriating the funds. More recently,

Indians have sued for money that appears to have been “lost” by the BIA. (Cobell v. Norton). The Cobell

case has been working its way through the court system for a few years and is not yet over.

If the federal government has a trust responsibility, how can Congress pass laws terminating tribes?

As Canby pointed out, the trust responsibility is enforceable against executive agencies, such as the Dept.

of Interior and the BIA, but the Supreme Court in Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock decided that congressional

policy towards Indians is not a subject for the courts. Congress is restrained only by the U.S. Constitution,

which in the case of Indians only discusses trade. This means that Congress can terminate the trust

relationship anytime it wants to, but tribes cannot terminate this relationship.

There is another problem in carrying out the trust responsibility when litigation is involved. When there are

legal disputes, the Dept. of Solicitor represents Indian interests until the case goes to court - then the Dept.

of Justice takes over. The Dept. of Justice often handles conflicts on the other side - against Indians, so you

have a single law firm, the Dept. of Justice, providing representation to Indians as both plaintiffs and

defendants. Since the BIA owes a duty to tribes, and the Dept. of Justice must enforce this duty, this has

sometimes created a situation where one federal agency is suing another. This results in the federal

government, in effect, suing itself.

A recent example of the conflict of interest that exists in the Dept. of Justice arose in the state of

Washington. The governor refused to negotiate gaming compacts with Washington tribes. A few tribes

were offering gaming without state compacts, in violation of federal law, so the U.S. attorney filed suit in

federal court to seize the tribes’ slot machines and close the casinos. The court decided that the U.S.

attorney should be acting in the best interests of the tribe and suing the state for refusing to negotiate a

compact, rather than taking action against the tribe for operating illegal gambling devices.

To take care of these conflicts, former President Nixon wanted to establish a separate legal agency for

handling representation of Indian interests. It seems like a good idea, but to date, this hasn't happened.

Religious Freedom

American Indian religions vary significantly from other western religions such as Christianity. Traditional

religion was not historically classified as a religion subject to protection by the First Amendment to the

U.S. Constitution. One of the goals in the 1800s was to “Christianize” Indians and lead them to civilization.

As late as 1921, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs stated that “The sun-dance, and all other similar

dances and so-called religious ceremonies are considered ‘Indian offences’ under existing regulations, and

corrective penalties are provided.”

In modern America, there are still problems encountered by followers of American Indian traditional

religions. One of these problems is that traditional religions are connected to the land. Some ceremonies

must be practiced in specific sacred areas at specific times of the year. In 1978, Congress passed the Native

American Religious Freedom Act (42 U.S.C. section 1996) to protect access to sites. The Act states:

That henceforth it shall be the policy of the United States to protect and preserve for American Indians their

right of freedom to believe, express, and exercise the traditional religions of the American Indian, Eskimo,

Aleut, and Native Hawaiians, including but not limited to access to sites, use and possession of sacred

objects, and the freedom to worship through ceremonials and traditional rights.

Three tribes in Northern California have sacred sites in the Six Rivers National Forest, which have been

traditionally used for ceremonial purposes. The Forest Service proposed to build a road through the forest

linking two towns. In Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association, the court found that the

ceremonies were an integral part of traditional religious belief. The ceremonies could be practiced only at

the particular sites in the national park and disturbing the natural state of the land would make the

ceremonies virtually impossible. What did the court decide? The court said that the government can use its

own land any way that it sees fit, regardless of whether or not Indians are negatively impacted, as long as

the government doesn’t coerce individuals into violating their religious beliefs or penalize their religious

activity, so the Indians lost in this case. The major problem with the American Indian Religious Freedom

Act is that it is only a declaration of policy. It contains no remedy for violations of the law.

There is federal land in Wyoming, known as Devils Tower National Monument. Devil’s Tower is a sacred

site for a number of tribes. It also provides some of the best rock climbing in the country. The Dept. of the

Interior tried to balance these competing interests. The most significant tribal ceremonial activities at

Devil’s Monument occur during the month of June, so the National Park Service closed Devil’s Tower

National Monument to commercial rock climbers during the month of June. A group of rock climbers sued

the National Park Service claiming that the June closures violated the First Amendment by favoring Indian

religions over other religions. How do you think the court decided in this case?

The court found that the closure violated the First Amendment to the constitution in that it supported

American Indian religion, so the National Park Service posted a notice asking climbers to voluntarily

refrain from rock climbing during the month of June. The climbers sued once again claiming that the

voluntary notice favored American Indian religions. What do you think the court decided this time? The

climbers pushed it too far this time. The court said that the voluntary request did not violate the climbers’

constitutional rights.

Courts have also rejected Indian attempts to prevent the federal government from building dams and

flooding sacred places and refused to block the development of a ski area on a sacred mountain.

The American Indian Religious Freedom Act contains a provision that directs the President to require

federal agencies to review their policies and procedures and identify changes needed to comply with the

federal policy stated in the American Indian Religious Freedom Act. From 1978-1979, a task force

identified 522 instances, affecting 70 tribes, where changes needed to be made. None of the task force’s

recommendations have been adopted.

There are also a number of cases in recent years regarding prisoners’ rights to religious freedom. Courts

have decided that prisoners have no right to use sweat lodges, since the use of sweat lodges must be

balanced against the need for prison security. It is up to each prison administration to determine if they

want to allow or prohibit the use of sweat lodges.

Peyote use is another area of religious freedom that has been addressed by Congress and the courts. The

Native American Church has religious ceremonies that include peyote use. There was a case in 1990 in

which two drug and alcohol counselors were members of the Native American Church and ingested peyote

during religious ceremonies. Word got back to their employers and they were fired. Oregon law classified

peyote as a controlled substance and provided for criminal penalties for its use and possession. (The case

originated in Oregon). The men applied for unemployment but were denied unemployment benefits, so

they sued – not for being fired, but to receive unemployment benefits. The Supreme Court held that

employees could be denied state benefits, including unemployment compensation, for using peyote on their

own time in religious ceremonies.

Congress reacted to this case by passing the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. The act specifically stated

that it was being passed in response to the Supreme Court’s decision and granted protection for sacramental

peyote use by Indians. The law provided that Indians ingesting peyote during church ceremonies were not

subject to criminal drug penalties for such use. The Supreme Court had the final say; however, and in 1997,

the court declared the act unconstitutional, so the court’s opinion in Employment Division, Dept. of Human

Resources of Oregon v. Smith is the current law regarding this subject.

Lecture 5

Tribal Governments

There were numerous tribal governments in America when the earliest settlers arrived, but there were no

institutions resembling that to which the settlers were accustomed, so they believed that no governments

existed. In fact, the Iroquois had a very advanced governmental structure, which later served as a model for

the American colonies.

One of the primary societal differences at the time of early contact was that tribes typically had oral

societies, reducing nothing to writing, while Anglo societies relied on the written word. Why wouldn’t

tribes have written societies? In many cases, tribes were nomadic. It would be difficult to haul file cabinets

full of documents with them when they moved from one encampment to another.

Ancient systems of government were disrupted as tribes were removed to western lands and placed on

reservations. The federal government took over most of the decision-making and internal control of tribes.

Only a few tribes, including New Mexico pueblos, escaped this fate. In some cases, the federal government

placed groups of Indians together on single reservations, even sometimes groups who were enemies,

because they shared a common language, even though they were from distinct political groups.

As you previously learned, the goal of federal policy during the allotment era was to assimilate Indians and

destroy tribal governments in a single generation. By the 1920s, very little was left of traditional tribal

structures. The Indian Reorganization Act strengthened tribal government, but not in the traditional sense.

Tribal governments were strengthened and encouraged, but only so far as they adopted the Anglo model

distributed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The model, as you saw earlier, required Secretary of

Interior approval of most activities, including enrollment. The BIA used this approval to control tribal

affairs. It was not uncommon for BIA representatives to regularly attend tribal government meetings.

Tribes that organized pursuant to the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) have standard constitutions and are

governed by a General Council, consisting of all adult members of the tribe, and a Tribal Council, which is

elected. The powers given to the Tribal Council vary from tribe to tribe. Many California tribes, who did

not adopt the IRA, have an IRA governmental structure, but they do not have a constitution or bylaws.

These tribes are governed by custom and tradition. The Tribal Council in this type of government retains

only those powers delegated by the General Council. Since there is no constitution, these powers can

change either by ballot or at any duly called meeting of the General Council. It is therefore much easier to

change the delegation of power when a tribe is following customs and tradition, than one that has adopted a

constitution.

Not all tribes have IRA or IRA-like governments. For example, the Mississippi Choctaw Tribe is governed

by a chief who reports to an elected tribal council on a quarterly basis.

There have been significant changes in tribal governments in the past 200 years. Traditionally, the role of

government was to adjudicate disputes. Tribal governments have now become more bureaucratic, with

some tribes using powers of taxation and regulation of various matters that affect the tribe. Tribal

governments more closely resemble state and federal governments, than traditional governmental

structures; however, tribal bureaucracy has not risen to the level of state and federal bureaucracy, partially

because their constituency is much smaller.

In many tribes, tribal leaders work full-time jobs and are not compensated for their positions on the tribal

council. It is still uncommon to find college-educated tribal council members. Although some tribes are

now developing junior colleges on their reservations, for many tribes the closest college is located some

distance from the reservation. Even if an individual is willing to leave his or her home to attend school,

what will happen after graduation? Job opportunities on many reservations are very limited so there are

often no jobs, and no prospects, at home to which the graduate can return. The choice then has to be made

whether to leave one’s culture to pursue a career, or forego the career and stay close to the culture.

Indian Judicial Systems

Traditional justice systems varied by tribe. Often the tribal chief, religious leaders or some type of council

served as the judicial body. Disputes were mediated. The role of the “judge” was to help the parties come to

an agreement between themselves and enforce tribal custom to keep harmony within the tribe. The goal of

punishment was to compensate for harm done, not to punish the criminal. Religious custom and tradition

were the basis for Indian justice and the “judge” often offered to compensate the injured party himself just

to keep harmony within the tribe. Banishment from tribes was very rare.

In contrast to traditional Indian justice systems, Anglo systems of justice are adversarial. There is always a

winner and a loser and harmonious relations are generally irrelevant. The goal of punishment in Anglo

systems is to punish those who break laws, often by putting them in prison and removing them from

society.

Courts of Indian Offenses - CFR Courts

In the early 1800s, Indians were being pushed west to reservations. The BIA was part of the War Dept. and

law and order was in the hands of the U.S. military. In 1849, the BIA became part of the Dept. Of Interior

and was placed under civilian control. Indian agents were responsible for law and order on reservations, but

some tribes retained some responsibility for law and order pursuant to treaties - mainly Indian vs. Indian

offenses.

Courts of Indian Offenses, or CFR courts, were created by the BIA to deal with law and order on

reservations and by 1883, the Courts of Indian Offenses were a regular part of BIA activities. The courts

were administered using specific rules published by the BIA in the Code of Federal Regulations, hence the

name, CFR courts. This marked the beginning of the evolution of separate branches of power within tribal

governments.

The legal status of these courts is unclear - only one federal case discussed the courts and it said that they

were merely educational and disciplinary instruments used by the U.S. government to improve the

condition of the dependent tribes. What about the separation of powers in the federal government? The BIA

is an executive agency that developed and implemented courts – a judicial function.

Allotment policies, beginning in 1887, increased the need for CFR courts because traditional forms of

government were disrupted. Families were divided to assimilate more quickly and these courts banned

some religious dances and ceremonies in the name of law and order. Indian judges staffed these courts but

Indian agents, who were generally non-Indians working for the BIA, selected the judges. The agents often

rewarded those Indians who were assimilating.

At their peak, CFR courts operated on about 2/3 of the reservations in the United States. Under the Indian

Reorganization Act, tribes could take back their judicial functions but the courts have continued in

existence on some reservations because some tribes lack resources to develop their own court systems.

Modern Tribal Courts

Tribal courts have extensive jurisdiction over civil matters within their boundaries and some criminal

jurisdiction. The Indian Civil Rights Act limits the maximum penalty that can be imposed by a tribal court

in criminal matters to one year in jail and/or a $5,000 fine. The result is that tribal courts generally only

hear misdemeanor offenses.

The Indian Reorganization Act allowed tribes to re-establish their own tribal justice systems. Establishment

of a tribal court system allowed tribes to use their customs and traditions in deciding matters before the

court, but after the allotment era, most tribes weren’t in a position to recreate what they once had. Some

traditional methods of dealing with disputes could not be revitalized because they depended on religious

ceremonies that were long since forgotten. In addition, by this time, many tribal members were Christians

and did not practice traditional justice that involved religious ceremonies so modern tribal courts often

followed a BIA model.

Most tribes now have courts and tribal codes that have been passed by their legislative bodies and approved

by the Secretary of Interior. The Tribal Justice Act was passed in 1994, which encourages development of

tribal courts. There are, however, a limited number of tribal courts in California. This can be attributed to

several factors. P.L. 280, by its grant of jurisdiction to the state, provides state forums for dispute resolution

and criminal prosecution. Even if tribes had tribal courts, matters could still be heard in state court, unless

jurisdiction is retroceded. Another obstacle to the development of tribal courts is the relatively small size of

California tribes. Few tribes have more than 1,000 tribal members, others have less than 100 tribal

members, and more than a few tribes have less than 20 tribal members. Federal resource allocations are