American System and Bank of US

advertisement

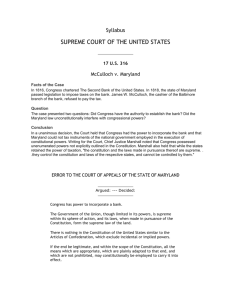

U.S. History Mr. Mintzes THE AMERICAN SYSTEM, BANK OF THE UNITED STATES AND AMERICA BEFORE ANDREW JACKSON The American System was a plan to strengthen and unify the nation. The American System was advanced by the Whig Party and a number of leading politicians including Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun and John Quincy Adams. The System was a new form of federalism that included: * * * * Support for a high tariff to protect American industries and generate revenue for the federal government Maintenance of high public land prices to generate federal revenue Preservation of the Bank of the United States to stabilize the currency and rein in risky state and local banks Development of a system of internal improvements (such as roads and canals), which would knit the nation together and be financed by the tariff and land sales revenues. It was based on the need to build an infrastructure that would improve transportation and allow the country to grow. Clay argued that the West, which opposed the tariff, should support it since urban factory workers would be consumers of western foods. In Clay’s view, the South (which also opposed high tariffs) should support them because of the ready market for cotton in northern mills. This last argument was the weak link. The South was never really on board with the American System and had access to plenty of markets for its cotton exports. Clay first used the term “American System” in 1824, although he had been working for its specifics for many years previously. Portions of the American System were enacted by Congress. The Second Bank of the United States was rechartered in 1816 for 20 years. High tariffs were maintained from the days of Hamilton until 1832. However, the national system of internal improvements was never adequately funded; the failure to do so was due in part to sectional jealousies and constitutional scruples about such expenditures. ERA OF GOOD FEELING The "Era of Good Feeling", a phrase first used in the Boston Columbian Sentinel newspaper on July 12, 1817 following the good-will visit to Boston of the new President James Monroe, is generally applied to describe the national mood of the United States from about 1815 to 1825. The period after the conclusion of the War of 1812 was marked by a lower level of concern over potential foreign intervention on the American continent, and a relative consensus over domestic policy illustrated in the lack of partisan factions. The Era reached its peak in the election of 1820, when President Monroe was re-elected with all but one electoral vote--a vote withheld only due to the voter's concern that George Washington should remain as the sole president elected unanimously. During that year, the bitter debate over slavery provoked by the application of the territory of Missouri to be admitted to the Union as a slave state was at least temporarily deferred with The Missouri Compromise, allowing Maine to split off as a separate state from Massachusetts and join the Union to counter the admission of Missouri, thus keeping the uneasy balance of slave and free states. The 1820 election also marked the effective end of the Federalist Party, which had lost popular support due to its opposition to the War of 1812, and opened a period where the Democratic-Republican Party initially established by Thomas Jefferson governed on the national level without substantial opposition. BANK OF THE UNITED STATES (1st and 2nd) In 1791, as part of his financial plan, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton proposed that Congress charter a Bank of the United States, to serve as a central bank for the country. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson opposed the notion on the grounds that the Constitution did not specifically give Congress such a power, and that under a limited government, Congress had no powers other than those explicitly given to it. Hamilton responded by arguing that Congress had all powers except those specifically denied to it in the Constitution, and that the "necessary and proper" clause of Article I invited a broad reading of the designated powers. President George Washington backed Hamilton, and the First Bank of the United States was given a 20-year charter. The charter expired in 1811. The First Bank of the United States, a private institution, was chartered by the Bank of England in 1791 and operated for 20 years as the government’s fiscal agent and depository of funds. Two thirds of the bank was owned by British interests. Political pressure by the DemocraticRepublicans prevented rechartering in 1811. However, the problems involved with waging war against Britain in 1812 pointed to the need for a central fiscal agent and sentiment for the BUS reemerged following the conflict. Second Bank of the United States In 1816, during the administration of President James Madison, the Democratic-Republicans reversed course and supported the creation of a Second Bank of the United States. It was patterned after the first and quickly established branches throughout the Union. The Second BUS's initial years were difficult and are largely remembered for its fraud and corruption. The Second BUS became a political issue again under President James Monroe, during the economic downturn accompanying the Panic of 1819. Many local state-chartered banks, eager to follow speculative policies, resented the cautious fiscal policy of the Second BUS and looked to state legislatures to restrict its operations. Critics again decried the bank’s mismanagement and conservative policies, and several states enacted legislation to restrict its activities by levying special taxes against it. The state of Maryland imposed a tax on the bank's operations, and when James McCulloch, the cashier of the Baltimore branch of the Second BUS, refused to pay the taxes, the issue quickly rose to the Supreme Court. In many ways, the opinion in that case represents a final step in the creation of the American federal government. In the case of McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), the state of Maryland argued that the federal government did not have the authority to establish a bank, because that power was not delegated to them in the Constitution. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall wrote the unanimous decision for the court that declared the tax imposed by the state of Maryland against the Second BUS was unconstitutional. To paraphrase Marshall, he conceded that the Constitution does not explicitly grant Congress the right to establish a national bank, but noted that the "necessary and proper" clause of the Constitution gives Congress the authority to do that which is required to exercise its enumerated powers. Thus, the court affirmed the existence of implied powers. The capstone of the creation of the American government was placed when the Supreme Court noted that: 1. The "necessary and proper" clause of the Constitution gives Congress the authority to do that which is required to exercise its enumerated powers in the case of McCulloch v. Maryland (1819). Thus, the court affirmed the existence of implied powers. 2. The Constitution and the laws made by the federal government are supreme. The federal government controls the states and cannot be controlled by them. A central banking system is central to American growth and independence. This became most evident during economic downturns and wars during the 18th and 19th centuries. America's modern central banking scheme, the Federal Reserve System was created by congress in 1913. The Second Bank of the United States provided a convenient way for the government to handle its affairs. The bank was created when James Madison and Albert Gallatin found the government unable to finance the country in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The War of 1812 had put the United States in significant debt, and the First Bank of the United States had closed in 1811. The debt of the nation led to an increase in banknotes among the new private banks, and as a result, inflation increased greatly. As a result, Madison and Congress agreed to form the Second Bank of the United States. After the war, despite the debt, the United States also experienced an economic boom, due to the devastation of the Napoleonic Wars. In particular, because of the damage to Europe's agricultural sector, the U.S. agricultural sector underwent an expansion. The Bank aided this boom through its lending, which encouraged speculation in land. This lending allowed almost anyone to borrow money and speculate in land, sometimes doubling or even tripling the prices of land. The land sales for 1819, alone, totaled some 55 million acres (220,000 km²). With such a boom, hardly anyone noticed the widespread fraud occurring at the Bank as well as the economic bubble that had been created.