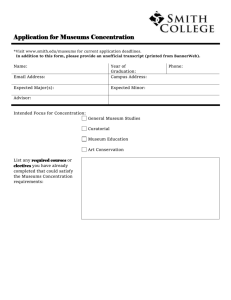

6 Museum-studies courses

advertisement