Native American – The dates for this period are very unclear

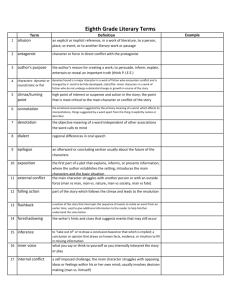

advertisement