Missing the Net: The Law and Economics of Alberta's NHL Players Tax

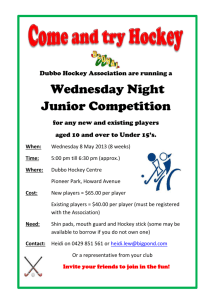

advertisement