Ralph Waldo Emerson - Unitarian Coastal Fellowship

advertisement

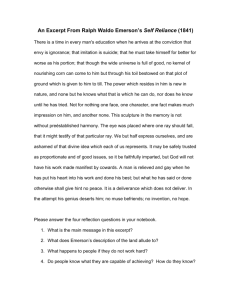

Ralph Waldo Emerson: Profile of a Moral Exemplar Unitarian Coastal Fellowship March 23, 2014 ©Rev. Sally B. White Ralph Waldo Emerson: Profile of a Moral Exemplar. Ralph Waldo Emerson was a leader of the Transcendentalist movement in American literature and philosophy. Some say he was the most important American cultural figure of the nineteenth century. And he was a Unitarian minister. What is the legacy, and the relevance to us, of this Unitarian forbear? Today’s is another in an occasional series of sermons examining moral and spiritual exemplars. Reading I’d like to preface the sermon with another reading from our hymnbook. These words are Emerson’s, from the essay “The Oversoul,” published in 1841. Let us learn the revelations of all nature and thought; that the Highest dwells within us; that the sources of nature are in our own minds. As there is no screen or ceiling between our heads and the infinite heavens, so there is no bar or wall in the soul where we, the effect, cease and God, the cause, begins. I am constrained every moment to acknowledge a higher origin for events than the will I call mine. There is deep power in which we exist and whose beatitude is accessible to us. Every moment when the individual feels invaded by it is memorable. It comes to the lowly and simple; it comes to whosoever will put off what is foreign and proud; it comes as insight; it comes as serenity 2 and grandeur. The soul’s health consists in the fullness of its reception. For ever and ever the influx of this better and more universal self is new and unsearchable. Within us is the soul of the whole, the wise silence, the universal beauty, to which every part and particle is equally related; the eternal One. When it breaks through our intellect it is genius; when it breathes through our will, it is virtue; when it flows through our affections, it is love. [STLT #531; The Oversoul] Sermon: I was sixteen when I first encountered Ralph Waldo Emerson. He spoke to something deep within me, and offered me a profoundly empowering and affirming vision of the universe and my own place in it. The encounter resonates still; and it likely had something to do with the fact that I am here this morning, with you, in this Unitarian Universalist church, and serving this congregation as minister. At the time, Emerson had been dead for 84 years. That fact is important; we’ll come back to it later. But for now, I’ll tell you it wasn’t a séance, or a dream, or an out-of-body experience. I was a sophomore in high school, studying American literature in English class. We were “up to” the 1840s and the Transcendentalists: Thoreau and his “Walden.” Emerson and “The Oversoul.” Two things stand out in my memory. 3 First was a fleeting glimpse of an idea connected to The Oversoul: that every person is animated by a spirit, a soul, which is a fragment of the spirit or the soul that animates the whole universe. That universal “oversoul”, is infinite and eternal; is before us and after us; is fully present in us; and when our small and bounded lives end, our own particular fragment or spark rejoins the whole. Nothing of soul or spirit is ever lost. There is a great balance, an unalterable completeness that takes different forms as days and years and ages roll on, and that is ever whole. I remember the term – oversoul – and the sense that what Emerson was saying meant that I am continuous with something larger than myself; something that includes me and contains me and sustains me, but not a personality, not a being who instructs or directs. And this idea was one that I had not before heard articulated, but in that moment I recognized it. I had a sense of rightness, of truth; a sense that Emerson said what I knew. And that sense of recognition, and of memory – Emerson writes about that, too. It’s there in his words in the reading before the sermon: “There is deep power in which we exist and whose beatitude is accessible to us. Every moment when the individual feels invaded by it is memorable.” I also remember a swelling pride. Emerson, and Thoreau, and all the Transcendentalists, were Unitarians. It was written right there in black and white in my English book. I noticed it particularly because I was a Unitarian, too. And at sixteen, I knew full well that Unitarian Universalism was less familiar and less well understood than the religions of my friends who were Catholic, or Methodist, or Presbyterian. At sixteen I knew how it felt when people told me they’d never heard of Unitarian Universalism, and when they asked what kind of church it was, and when I tried to find words 4 to express what we believed and what I believed and what my religion meant to me. How exciting to be able to say that I was a part of the church of these famous people, important thinkers, shapers of American literature and culture. This sense of pride in our forbears and famous fellow-members is not unique to me; the pamphlet “We Are Unitarian Universalists” that we offer to visitors who want to know more about Unitarian Universalism includes a short list of UUs we boast about– and Ralph Waldo Emerson is one! I think most people know something about Emerson even if they don’t connect him with Unitarianism – that’s why we can – and do – brag about him in our literature. My own story is atypical: I was familiar with Unitarian Universalism before I encountered Emerson. Reading about him came to me as an affirmation of my Unitarian Universalist identity. But far more fundamental is the affirmation that Emerson would surely say is primary: that my own essential nature is continuous with the essential nature of the universe, and therefore I participate in all that is true. And therefore, I can know what is true by paying attention to what I know. In 1831, when he was only 28, Emerson realized: “my own mind is the direct revelation I have from God.” [Robert D. Richardson, Jr. Emerson:The Mind on Fire. p. 117]. It is not easy, and it is not common among people, to know one’s own mind. In 1841, in an essay called “Self Reliance,” he wrote, “A [person] should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across [their] mind from within…” And then he completes the thought: …”more than the luster of the firmament of bards and sages.” Second-hand wisdom is derivative; it is dull and dead. Surely it is easier to accept as true 5 what someone else tells you is true, but the point is not ease, it is insight. It is experience. And it is experience refined in conversation with others, for each of views the world from a slightly different perspective; each of us hears the direct revelation – from God, or of God – each of us hears and understands slightly differently, and it is important for us first to observe, and then to reflect, and then to test our insights against the insights of others. The great end of all of this is the unfolding of the powers that lie within us from birth – from before birth. Education, development, self-consciousness, self-expression – becoming who we are, and knowing ourselves to be entirely real and ideal, body and soul, temporal and eternal, and, like the rose, perfect in every moment of our existence. This is the irony of my encounter with Emerson: it came not through direct experience of the man and his ideas but through reading his writings – greatly excerpted for a high-school English book, and then reflected upon not by Emerson himself, but instead by an editor whose name is lost to me. This is the irony of reading those writings more than eighty years after his death, and more than 125 years after they were first written. And it is the irony of Emerson’s life that he himself is honored and remembered as a bard and a sage. Ralph Waldo Emerson was born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1803. His grandfather had been a chaplain to the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War; Ralph’s father, a Unitarian minister, died when Ralph was not quite eight. He went to Harvard, which was more like a preparatory school than today’s colleges, and graduated in 1821 at the age of eighteen. There was a strong presumption that he – and his brothers – would also go 6 into ministry; two of his brothers instead became lawyers. After graduation Ralph (who now called himself Waldo) taught school for several years. And he read. He read philosophy: Plato and Socrates, and contemporary Scottish and English and French philosophers; he read Goethe; he read the Bible, and the contemporary criticism of the Bible, and theology; he read poetry, especially the English romantic poets – Blake, Coleridge, Wordsworth. He read science: botany and geology and astronomy and natural philosophy; he read . And he journalled. He took notes on all he read, and he recorded his reactions, his responses, his thoughts and feelings about the steady stream of new ideas he sought out and took in. There now exist 16 volumes of published “Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks” and more than 50 unpublished notebooks; in later years, he indexed his journals and later yet, he indexed the indexes. Here is where he recorded the germination and the growth of all his ideas. In 1829, when he was 26, Emerson was ordained to the Unitarian ministry at the Second Church in Boston. That fall, he married Ellen Tucker. Less than two years later, Ellen died of tuberculosis. Her death devastated Waldo, and deeply affected his sense of how he would and how he could live his life. Parish ministry had offered him the stability and respectability to establish a home and a family, but it demanded of him a conventionality and tactfulness that began to feel like hypocrisy. In October 1832, he resigned the ministry of Second Church, having concluded that, “in order to be a good minister, it was necessary to leave the ministry.” [Emerson:The Mind on Fire. p. 126] But Emerson was a powerful public speaker. For several years after resigning his pulpit, he preached occasionally or for months at a time in 7 various New England churches. And in 1834 he began a new career as a lecturer. He would create a series of talks on a subject – a series on “Biography,” for example, profiled Quaker George Fox as an exemplar of the sentiment of religion Martin Luther as an exemplar of reform, Michelangelo of art, Milton of poetry. For nearly 50 years – until his death in 1882 – Emerson delivered as many as 80 lectures per year; perhaps 1500 lectures in his lifetime. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Waldo_Emerson]. The writings in his journals and notebooks found their way into the lectures; the lectures were re-worked into essays. Over the course of his life, Emerson published two collections of essays, two books of poetry, and at least six books based on lecture series. In 1835 he married again; this marriage, to Lydia Jackson (whom he called Lydian) lasted the rest of his life. The couple had four children, three of whom lived to adulthood. And they settled in Concord, Massachusetts, west of Boston. Not only books, but also letters and conversations and decades-long friendships fed Emerson’s ever-seeking mind. Three times he visited Europe, including England and Scotland; he met Coleridge, Wordsworth, and the Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle. William Ellery Channing was a mentor when Emerson was young; Channing’s nephew Ellery was a neighbor and friend in Concord, as was Henry David Thoreau. He knew Nathaniel Hawthorne and Walt Whitman and Oliver Wendell Holmes. He traveled in the United States lecturing; he met Abraham Lincoln. And he was the founder and the heart of the circle of New England Unitarian thinkers and dreamers known as the Transcendentalists. This group, which 8 included Bronson Alcott (Louisa May’s father) and Thoreau and Channing and Theodore Parker and (informally) Margaret Fuller and perhaps a dozen more were ultimately struggling to bring to birth a uniquely American mind and worldview. Transcendentalism is taught in the high schools as a literary movement, but in truth it was a religious upheaval – young Unitarians agitating for a religion of experience rather than of revelation and scripture. (It was Emerson addressing the graduates at Harvard Divinity School and telling them to preach not the Bible but [your] life, - life passed through the fire of thought.” [Conrad Wright. Three Prophets of Religious Liberalism. P. 103]. Young Americans agitating for and American experience, rooted in the wide landscape of the American continent and not the ancient history of Europe and England. Young dreamers critiquing not only the religion of their teachers and preachers and fathers, but critiquing also the politics and the social structure that follow from that old and backward-looking religion. [Perry Miller. The Transcendentalists. pp. 8-15]. Historian Perry Miller says of Transcendentalism that on the one hand, “America adopted it and made it orthodox,” and on the other “it consumed, shattered and destroyed its adherents.” I would say that Emerson, who lived to be 79 years old, never abandoned Transcendentalism, but that his powers ripened in an irony that saw him become famous, become one of those bards or sages he had long ago warned about. Emerson, whose grandfather took part in the American Revolution, lives on in this age of virtual reality and virtual relationships by virtue of his writings that still inspire, and still challenge. “Fundamental perceptions are intuitive and inarguable;” he wrote, “all important truths, whether of physics 9 or ethics, must at last be self-evident.” And, “The days are gods. That is, everything is divine.” On this day, take a moment now, in silence, to consider all that we have heard this morning, spoken and unspoken. The bell will lead us into silence, and music will lead us out. Bell Silence Music Amen.