Kidney Biopsy Teaching Case

advertisement

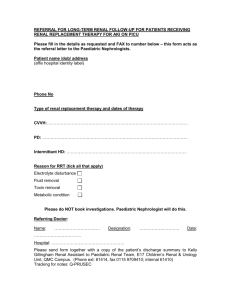

Clinical Neprology Case Report Peculiar Renal Endarteritis in a patient with Acute Endocapillary Proliferative Glomerulonephritis Takehiko Kawaguchi, Asami Takeda, Yoshiaki Ogiyama, Yukako Yamauchi, Minako Murata, Taisei Suzuki, Yasuhiro Otsuka, Keiji Horike, Daijo Inaguma, Kunio Morozumi Department of Nephrology, Japanese Red Cross Nagoya Daini Hospital, Nagoya, Japan Corresponding Author: Takehiko Kawaguchi, MD, MPH, PhD Department of Nephrology Japanese Red Cross Nagoya Daini Hospital Tel: +81-52-832-1121 Fax:+81-52-832-1130 kawatake45@gmail.com Running Title: Renal Endarteritis with Acute Glomerulonephritis Character Count: 12,179 (including spaces, limit 24,000) ABSTRACT Acute glomerulonephritis (AGN) is one of the most common renal diseases which are often associated with infections, often resulting in diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis (GN). This report reviews an interesting case in which renal endarteritis coexisted in AGN with diffuse endocapillary proliferation. The discussion highlights important pathological findings and clinical aspects in acute endocapillary proliferative GN with renal endarteritis. Coexisting endarteritis should be in the differential diagnosis of AGN in patients with persistent clinical courses. Key Words: acute glomerulonerphritis (AGN) - diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis (DPGN) renal endarteritis 1 CASE REPORT Clinical History A previously healthy 41-year-old woman presented to a clinic with one week history of general fatigue and slight fever after traveling to Hokkaido, the northern part of Japan. There was no history of upper respiratory symptoms and gross hematuria. The patient denied rashes, arthralgia, myalgia, and weight loss. Oral antibiotics (cefcapene, 3rd generation cephem) and non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) were prescribed at the clinic for a few days, but these drugs did not improve the symptoms. She presented with the subsequent peripheral edema and 5 kg weight gain to the emergency room of our hospital, and in view of acute kidney injury (AKI) with proteinuria and edema she was admitted for workup. On physical examination, she was 1.57 meters tall (5 feet 2 inches) and weighed 48.1kg (106 pounds) (43.1kg, 95 pounds, before the onset of symptoms) with body mass index of 19.5 kg/m2. Heart rate was 73 beats/min and regular, and blood pressure was 107/64 mm Hg. Body Temperature was 37.1℃. Except for pretibial pitting edema, the remaining physical examination findings were unremarkable. She had normal heart sounds with no murmurs. Lungs were clear to auscultation. Her abdomen was soft and non-tender. No lymphadenopathy or organomegaly was noted. Neurological and musculoskeletal findings were unremarkable. There was no skin rash, erythema, or purpura. Electrocardiogram and chest radiograph showed no abnormalities. Abdominal ultrasonography showed normal-sized kidney without obstruction. 2 Laboratory Data Laboratory tests showed the following values: hemoglobin, 10.2 g/dL; white blood cell count, 3,900/μL; platelets, 107,000/μL; blood urea nitrogen, 35.6 mg/dL (12.7mmol/L); serum creatinine, 2.1 mg/dL (181 μmol/L), with an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 22 mL/min/1.73m2; albumin, 2.98 g/dL; total protein, 5.75 g/dL; and microscopic hematuria and proteinuria (protein, 1.6g/gCr); C-Reactive protein (CRP), 1.04 mg/dL; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), 52 mm/h; immunoglobulin G, 1,047 mg/dL; immunoglobulin A, 299 mg/dL; immunoglobulin M, 136 mg/dL; complement components, C3, 66 mg/dL (normal, 69 to 128 mg/dL); C4, 25 mg/dL (normal, 14 to 36 mg/dL); CH50, <12 U/mL (normal, 25 to 48 U/mL); antistreptolysin-O (ASO) titer, 66 IU/mL (normal, less than 166 IU/mL); antistreptokinase (ASK) titer, 5,120 (normal, less than 640); positive antinuclear antibodies (×40); positive SSA titers 251 (range, 0 to 0.9); negative anti-SSB; negative anti–double-stranded DNA antibody titers, negative antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), negative cryoglobulin. Serological tests for hepatitis B, C, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were negative. Serum immunoassays for Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Human herpes virus 6 (HHV6), Parvovirus B19, were negative, while Herpes Simplex virus (HSV) IgM/IgG were positive (IgM 3.52, (normal, less than 0.80), IgG 52.5 (normal, less than 2.0)). Kidney Biopsy A percutaneous kidney biopsy was performed on admission day 4 to determine the cause of AKI 3 with urinary abnormality and edema. On light microscopy, 73 glomeruli were present, of which 2 was globally sclerosed. Any glomeruli show significant endocapillary proliferative features and marked infiltration of mononuclear (MN) cells, not polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes (Fig 1-A), some of which presented mitotic changes (Fig 1-A, arrow head). They also showed mesangiolysis with loss of tethering of the capillary walls of the glomerular basement membrane to mesangium (Fig 1-A, thin arrow). There were no crescents or adhesions. Glomerular basement membranes did not show spikes or pinholes, and capillary walls showed no double contours. There was no tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis. Interlobular artery and its branch showed endarteritis mainly with MN leukocytes, not PMN cells (Fig 1-B). In addition, fibrinoid necrosis was noted in the walls of the branch of the artery (Fig 1-B, thin arrow). There was no evidence of thrombosis or emboli. In immunohistochemical studies, KP1 positive cells, derived from monocytes, were dominant both in endocapillary proliferation and in endarteritis, with minor CD3 positive cells, from T cells (Fig 1-C, D). Immunofluorescent (IF) studies showed a “full house” deposition (positive for C3, C4, C1q, IgG, IgA, and IgM) with a fine granular pattern both in the mesangium and in the peripheral capillary walls (Fig 2). No arteries or arterioles showing vasculitis were included in the IF sample, while peroxidase antiperoxidase (PAP) methods showed no deposition of any immunoglobulin in the same artery with endarteritis in the LM sample, suggesting pauci-immune type with no immune complex. Electron microscopy (EM) showed endocapillary proliferation, and many subendothelial deposits (Fig 3, arrow head), with no subepithelial hump. No organized structures of curved microtubular aggregates, typical of 4 cryoglobulin deposits, were found at super high magnification (×27,000). Diagnosis Diffuse endocapillary proliferative glomerulonephritis (GN), immune complex mediated, with focal endarteritis, pauci-immune type. Clinical Follow-up It was firstly decided to closely follow up the patient with symptomatic management of edema and fever, and no immunosuppressive or antibiotic agents were added because the biopsy suggested acute endocapillary proliferative GN, which was supposed to be self-limiting. One week after the biopsy, serum creatinine and urinary protein level had decreased and peripheral edema had ameliorated. Additionally, hypocomplementamia was improved. However, fever with headache continued and serum inflammatory markers had gradually increased (CRP, 4.81 mg/dL; ESR, 104 mm/h). As blood, urine and spinal fluid cultures ruled out the present bacterial infection, the subsequent elevated inflammation may be attributed to vasculitis as observed on the biopsy specimen. The patient was treated orally with prednisone 20mg per day. After the initiation of the treatment she made a remarkable recovery with no fever and decreased inflammation (CRP, 0.37 mg/dL; ESR, 31 mm/h), and discharged on day 15. During the outpatient follow-up, prednisone was tapered and off in 6 weeks, with no relapsing the general and renal symptoms (Cr, 0.76 mg/dl; CRP, < 0.2mg/dl; C3, 81 mg/dL; 5 C4, 19 mg/dL; CH50, 23.9 U/mL; ASK titer, 1,280). DISCUSSION We presented an interesting kidney biopsy case of acute endocapillary proliferative GN with renal endarteritis. Based on the occurrence after a feverish event, hypocomplementemia, and its relatively benign clinical course, this case was clinically expected to be post infectious acute GN (PIAGN), although the pathogen or infectious site was not clearly identified by an extensive serological and radiological workup. This case showed diffuse endocapillary proliferative change, one of the most typical histological features of PIAGN. Not only streptococcus but also various pathogens are known to cause AGN with diffuse endocapillary proliferation [1][2]. Glomerular subepithelial humps, often seen in post streptococcal acute GN (PSAGN), were not found in this case, but glomerular humps may be less prominent in non-PSAGN and more intramembranous or subendothelial deposits can be found [3]. However, some pathological features in the case were inconsistent with typical PSAGN or PIAGN; MN cells infiltration in endocapillary proliferative change and a “full house” deposition in IF study. PMN leukocytes usually dominate in early stages of endocapillary proliferation in PSAGN or PIAGN [4][5], but MN leukocytes were dominant in this case. A “full house” deposition in immunofluorescence study was also inconsistent with typical PSAGN or PIAGN, characterized mainly by IgG and C3 deposition. IF patterns vary enormously according to the causative antigens of AGN, but full house deposition of PIAGN were previously described in a very few reports [6][7]. In 6 spite of no typical clinical symptoms of oral or genital lesions, the serum immunoassay, positive HSV IgM antibody, may suggest the possibility of the acute HSV infection, but the association between HSV and the renal pathological changes was unclear. HSV-induced endocapillary proliferative GN has never been described bibliographically, while the previous report suggested the relationship between HSV infection and giant cell arteritis, not renal endarteritis [8]. Renal endarteritis itself is a rare finding coexisting in acute GN (AGN). Small arteritis or endarteritis often coexists in the secondary GN associated with systemic disease, such as lupus nephritis (LN) [9], cryoglobulinemic glomerulopathy [10], and hypocomlementemic urticarial vasculitis. However, clinical examinations and laboratory findings ruled out these systemic diseases. Though this case showed diffuse global endocapillary proliferation with a “full house” deposition in IF study, resembling the pathology in LN class IV according to International Society of Nephrology / Renal Pathology Society [ISN/RPS], the patient did not meet criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus from the American College of Rheumatology. Cryoglobulinemic glomerulopathy was also considered in the differential diagnosis of the endarteritis, but no organized structure of cryoglobulin was found in the EM sample. Additionally, the endarteritis was pauci-immune type with no immune deposit. Given the MNC infiltrates in endarteritis, the same type of inflammatory infiltrates as those in endocapillary proliferative lesion, the pathogenesis of the endarteritis and the endocapillary proliferation may possibly be identical. However, it may be difficult to categorize this clinicopathology into any established type of GN. 7 Further investigations are required to clarify the pathophysiological relationship between the GN and its coexisting endarteritis. The renal prognosis of this case was as excellent as that of typical PIAGN. An initial episode of acute renal failure with PIAGN is not necessarily associated with a bad prognosis [11]. The management is generally supportive, with salt restriction and diuretics to control of edema, and, if necessary, treatment of high blood pressure and electrolyte abnormalities. Treatment of PIAGN remains empirical because of the absence of therapeutic clinical trials, and immunosuppressive treatment is rarely recommended. In this case, however, fever and elevated inflammation was not self-limiting. This case was characterized by endarteritis coexisting in acute endocapillary proliferative GN, and we may attribute the inflammation and the subsequent fever to the coexisting endarteritis observed on the biopsy specimen. Some cases of clinically diagnosed PIAGN with a persistent course should be recommended to undergo renal biopsy to confirm the diagnosis, in some of which corticosteroids or other immunosupressants may be considered for coexisting vasculitis. In summary, we described a peculiar renal endarteritis in a patient with AGN with endocapillary proliferation. Renal endarteritis is a rare finding coexisting in AGN and not consistent with the typical pathological feature of common PSAGN or PIAGN. Coexisting endarteritis should be in the differential diagnosis of AGN in patients with persistent clinical courses. Further studies are needed to identify the cause and the pathogenesis of renal endarteritis with endocapillary proliferative GN. 8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Research Support: None Financial Conflict of Interest: None 9 REFERENCES 1. Schena FP. Renal manifestations in bacterial infections. Contrib Nephrol 1985;48:125. 2. Zarconi J, Smith MC. Glomerulonephritis: Bacterial, viral, and other infectious causes. Postgrad Med 1988;84:239. 3. Nadasdy T, Silva FG. Acute postinfectious glomerulonephritis and glomerulonephritis caused by persistent bacterial infection. In: Jennette JC, Olson JL, Schwartz MM, Silva FG ed. Heptinstall’s Pathology of the Kidney. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007:357. 4. Jones D. Inflammation and repair of the glomerulus. Am J Pathol 1951;27:991. 5. Jones DB. Glomerulonephritis. Am J Pathol 1953;29:33. 6. Smet AD, Kuypers D, Evenepoel P, et al. ‘Full house’ positive immunohistochemical membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis in a patient with portosystematic shunt. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2001;16:2258. 7. Lee LC, Lam KK, Lee CT, Chen JB, Tsai TH, Huang SC. “Full house” proliferative glomerulonephritis: an unreported presentation of subacute infective endocarditis. J Nephrol 2007;20:745. 8. Powers JF, Bedri S, Hussein S, Salomon RN, Tischler AS. High prevalence of herpes simplex virus DNA in temporal arteritis biopsy specimens. Am J Clin Pathol 2005;123:261. 9. Appel GB, Pirani CL, D’Agati V. Renal vascular complications of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Soc Nephrol 1994;4:1499. 10. D’Amico G, Fornasieri A. Cryoglobulinemic glomerulonephritis; A membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis induced by hepatitis C virus. Am J Kidney Dis 1995;25:361. 11. Ferrario F, Kourilsky O, Morel-Maroger L. Acute endocapillary glomerulonephritis in adults: A histologic and clinical comparison between patients with and without initial acute renal failure. Clin Nephrol 1983;19:17. 10 Figure Legends Figure 1. Light microscopy. (A) Endocapillary proliferation with mesangiolysis (arrow) and mitosis (arrow head) (periodic acid-Schiff staining; original magnification ×200) (B) Endarteritis in the interlobular artery, and fibrinoid necrosis (arrow) in the branch of the artery (Elastica-Masson Staining; original magnification ×100) (C) (D) Expression of JC70a (a), KP1 (b), CD3 (c), L26 (d), in glomeruli (C) and interlobular artery (D). KP1 positive cells, derived from monocytes, were dominant both in endocapillary proliferation and in endarteritis, with minor CD3 positive cells, from T cells. L26 cells, from B cells were rarely present. (immunohistochemical staining; original magnification ×200 (C), ×100 (D) ) Figure 2. Immunofluorescence microscopy. A “full house” deposition (positive for C3, C4, C1q, IgG, IgA, and IgM) with a fine granular pattern both in the mesangium and in the peripheral capillary walls. (original magnification ×200 ) Figure 3. Electron microscopy. Electron dense deposits in subendothelial space, with no subepithelial deposits or no organized structures (original magnification ×10,000 ). 11