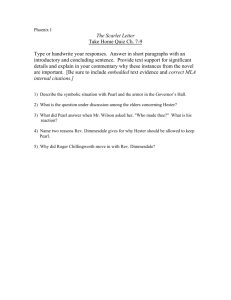

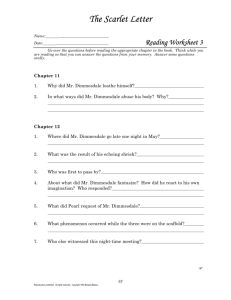

Chapter Three

advertisement