Water In The Atmosphere \\mailmoc\mocfsa_workgrps\Courses

advertisement

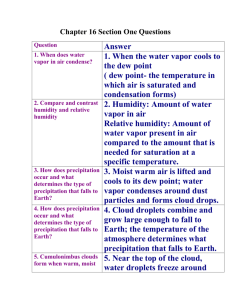

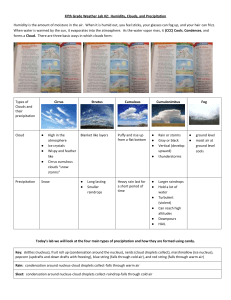

Met Office College - Course Notes Water in the atmosphere Contents 1. Introduction 2. Dew and frost 3. Raindrops 4. Snow 5. Hail 6. Lightning and thunder 7. Fog 8. Drizzle and snow grains Crown Copyright. Permission to quote from this document must be obtained from The Principal, Met Office College Page 1 of 10 Last saved date: 9 March 2016 FILE: MS-TRAIN-COLLEGE-WORK-D:\533580286.DOC 1. Introduction It need hardly be said that water is important – we would not be here if it were not for its existence. However, it is not only in sustaining life that it plays a prominent role but also in meteorology. The formation of clouds, precipitation processes, and the release or absorption of latent heat due to phase changes are integral to the atmospheric system. (By ‘water’ we are not restricting attention solely to the liquid phase but referring generally to H2O in its liquid, solid and gaseous forms.) Much of the weather we experience (particularly in the UK) is directly affected by water. But water is no ordinary substance – its behaviour is distinctive, even peculiar, particularly when phase changes are involved. It is these manifestations of water as we experience it that is the subject of these notes. In the following sections, each of the main contexts in which water makes its presence known will be discussed. 2. Dew and frost When a jug full of iced drink is taken out of a refrigerator, water droplets condense on the outside of the container (provided the jug is made of material which is a good conductor of heat, such as metal). This happens because the jug is at a lower temperature than the dew-point of the air. “Dew-point” is defined as the temperature at which the air, when cooled, will just become saturated (at constant pressure and constant ‘relative humidity mixing ratio’). On a summers day when the air temperature reaches 18 °C, the dewpoint might typically be 8 °C. By sunset the air temperature may have fallen to 12 °C (see Fig. 1) but the dew-point will still be around 8 °C. During the night the ground temperature continues to fall and if it reaches, say, 7 °C the temperature of the ground is below the dew-point (the saturation point) of the air and droplets of moisture begin to form this is dew. Due to the release of latent heat when the dew is formed, the fall in temperature slows down. Next morning, as the incoming solar radiation gathers strength, the dew will be evaporated. The grass will become reasonably dry and suitable for sitting upon during the day. However, in winter in calm weather the daytime evaporation may be so slow that dew may persist all day. Hoar frost is composed of tiny ice crystals “feathery” in appearance when well developed; the crystals are especially feathery when the dew point is below 0°C. It is formed by the same process as dew, but occurs when ground temperatures are below freezing-point. A ground frost may occur when the air temperature does not get down to freezing- Page 2 of 10 Last Saved Date: 9 March 2016 File: ms-train-college-work-d:\533580286.doc point. Consequently when the grass is covered in a white hoar frost at dawn it cannot be assumed that there has necessarily been an air frost. Temperature Dew forms when ground temp. falls to dewpoint Dew evaporates 2-3 hours after sunrise Midday Sunset Midnight Sunrise Midday Fig. 1. A simplified diurnal temperature curve. Possible points at which dew may form and evaporate are indicated. The actual time of dew formation and evaporation depends upon the amount of moisture in the air, the nature of the underlying surface, and other factors. Sometimes dew forms during the evening and subsequently freezes to become hoar frost with globular ice on the grass. There is a weather saying of some value: “Dew at night, the day will be bright”. To a certain extent this is self-evident, for dew tends to form on clear, calm nights which occur in anticyclonic (high pressure) weather. Such conditions also tend to give sunny days. 3. Raindrops The windscreen of a car is a superb place to view raindrops, and indeed all precipitation particles. Every second or two the windscreen wipers provide a fresh screen on which to view the next sample. Water drops larger than 0.5 millimetres in diameter are classed as rain, whereas smaller drops are described as drizzle. The difference is purely one of drop size rather than the intensity of precipitation. Usually drizzle comes from sheets of low shallow cloud, whereas rain is more likely from deeper clouds. Drizzle, with its many small drops, will cut down the visibility more than the equivalent amount of water falling as rain. Also heavy drizzle is more wetting than slight rain. In the early days of meteorology it was known that rising air would cool and its water vapour would condense into tiny droplets of water to form a cloud. Within the cloud the large drops would tend to grow by colliding and merging with the smaller ones (a process called coalescence) - this appeared to provide the explanation of how rain was Page 3 of 10 Last Saved Date: 9 March 2016 File: ms-train-college-work-d:\533580286.doc produced (see Fig. 2). During the 19th and early 20th centuries scientists became aware that the rate of growth of water droplets by this mechanism was too slow to account for the formation of large raindrops, though it did explain drizzle. Large drops: fall speed ~10m/s Small drops: negligible fall speed Fig. 2. A large rainfall falls rapidly and, with its large cross-sectional area, ‘sweeps up’ small droplets from its path. In 1933 Bergeron demonstrated that ice crystals could play an important part in the formation of raindrops. In certain conditions ice crystals form in clouds and rapidly increase in size at the expense of the neighbouring water droplets. Collisions between the ice crystals then lead to snowflakes. It is then possible to get large raindrops when the snowflakes melt as they fall through air which is above freezing. This process is responsible for most of the rain and snow over the British Isles. In the summer months large raindrops are often particularly noticeable when they fall from medium-level clouds on a hot afternoon. The first few drops may spread out on a path to the size of a 2p piece. Such “fullsize” raindrops are sometimes the precursor of thundery weather. 4. Snow Snow forms typically at temperatures well below freezing, say -10 °C , inside a cloud where ice crystals grow at the expense of tiny supercooled water droplets (i.e. droplets of water with temperature below freezing). This is the Bergeron-Findeisen process - the end result is snow. When snowflakes fall out of the bottom of the cloud, their rate of descent is slower than rain (perhaps by a factor of 5). If the snow reaches a level where the air is above freezing then obviously it will melt, but at the same time the air will be cooled. In practice, snow will often reach the surface with a temperature of 1 °C or 2 °C. Partly melted snow, called sleet, is likely at temperatures around 2°C or 3 °C. The notion that it can be too cold for snow is erroneous, Page 4 of 10 Last Saved Date: 9 March 2016 File: ms-train-college-work-d:\533580286.doc although heaviest falls do tend to occur with temperatures around freezing. Individual ice crystals can be the shape of prisms or plates or, with typical snowfalls, 6-pointed stars. The medium to large snowflakes normally seen in the British Isles are composed of many ice crystals which have collided and stuck together (aggregated) inside the cloud, and thus snowflakes may be 3 cm across. If 10 cm of fresh fallen snow is collected in a tall glass and allowed to melt, it is found that the water equivalent is about 1 cm. However, the result does vary with different snowfalls and also depends on how carefully the snow is collected. On the Scottish mountains almost any front or depression can give some snowfall in winter. The lowlands of England, though, need perhaps an approaching warm front or occluded front, or an active depression passing just to the south of the observer (see Fig. 3). A showery northerly is another possibility, with snow showers coming in from the sea. Cold fronts which, by their name, sound as if they should bring snow tend to be disappointing in this respect. However, sometimes rain will turn to snow behind the front before the precipitation ceases. On low ground in the British Isles, October is very early for snow and June is very late - though notable falls in eastern England occurred on 2nd June 1975 delaying cricket matches and causing raised eyebrows on the farm. Summer observations of “snow” usually turn out to be falls of Rain and possible snow Low Rain soft hail, but in meteorology virtually nothing is impossible. Fig. 3. If an active depression crosses the British Isles in winter then snow is possible to the north of its track, with rain to the south. Page 5 of 10 Last Saved Date: 9 March 2016 File: ms-train-college-work-d:\533580286.doc 5. Hail There are three different phenomena that could loosely be described as hail which affect the British Isles. Snow pellets are beautifully white but easily crushable between the fingers. They are occasionally called “soft hail”. Ice pellets are quite moderate in size and are composed of dear ice, sometimes conical in shape. Hailstones are whitish in appearance and vary greatly in size. If a hailstone is cut open a layered structure like an onion is sometimes apparent (see Fig. 4). Fig. 4. A large hailstone may consist of several layers of clear and opaque ice. Large hailstones fall from deep cumulonimbus clouds. The cloud base may be 2,000 feet above the ground with tops at 30,000 feet. Much of the cloud will be composed of supercooled water droplets. The way in which hailstones are formed is still the subject of some controversy. One theory is that they grow to a large size by repeated recirculation within the cloud and where updraughts are strong enough to support them. As the hailstone falls it will collect tiny water droplets which freeze and form a layer of ice. Perhaps the hailstone will then be caught in a vigorous updraught. As it is carried back higher into the cloud it collects more minute water or ice particles to form another layer of ice. Thus layers build up on the hailstone (made of alternate layers of clear and opaque ice) and the cycle may be repeated until the stone is so big that it falls to earth. Hail showers are quite common over the British Isles in westerly and northerly airstreams in spring, but really large hailstones tend to occur in the south and are very much a feature of the summer months. Some dramatic temperature falls accompany hailstorms with the transition from sunshine to hail-covered ground taking less than an hour. Strong gusts of wind may also occur, and so too may lightning and thunder. The largest hailstone recorded in the British Isles weighed 141 grams and occurred at Horsham, Sussex on 5 September 1958. Certainly anything approaching golf-ball size is remarkable, but hailstones can grow large enough to dent cars, shatter greenhouses and even injure Page 6 of 10 Last Saved Date: 9 March 2016 File: ms-train-college-work-d:\533580286.doc people. The USA, Canada, central Europe, the southern parts of the USSR, India and China all experience large hail. So too do land areas in the southern hemisphere. The world record quoted of 758 grams was from Kansas, USA with a diameter of 190 millimetres. 6. Lightning and thunder Lightning is one of the most impressive displays of atmospheric energy and yet - despite all the studies that have been carried out - the mechanism by which the electrostatic potential develops in the atmosphere is not fully understood. Lightning occurs when a charge builds up within a cloud (see Fig. 5). A difference in charge then exists between that region of the cloud and the ground, or between the cloud and another nearby. The charge is thought to build up on ice particles or water droplets. If the difference in potential becomes sufficiently great, “the spark jumps the gap” between cloud and ground or between neighbouring clouds. Intense heating along the discharge path causes very rapid expansion of the air —the ‘explosive expansion’ causes the thunder. When the path of the discharge can be seen the lightning is described as “forked”, but “sheet” lightning occurs when the flash is obscured by cloud. + + + + + + + + _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ + + _ _ _ + + _ _ _ Fig. 5. The distribution of charge within a typical cumulonimbus cloud. The discharge may be cloud-to-cloud or from cloud to ground. Since light travels at 300,000 kilometres per second the flash is seen almost instantaneously. Sound, on the other hand, travels 1 kilometre in 3 seconds (1 mile in 5 seconds). To find out how far away the thunder is, count the seconds as soon as the lightning is seen and continue until the thunder is heard. Then divide by 5 to get the storm distance in miles. In England and South Wales, thundery days occur mostly in the summer half-year when southerly or south-westerly winds at medium or high levels bring storms up from France. Such storms often occur at night. Inland areas of eastern England tend to be the most prone to Page 7 of 10 Last Saved Date: 9 March 2016 File: ms-train-college-work-d:\533580286.doc thunderstorms where they occur on 10 to 20 days per year. In Scotland, Northern Ireland and North Wales thunderstorms are less common and generally occur at any one site on fewer than 10 days per year. Also such storms may be one flash and a bang and they have gone. Lightning accompanied by snow can occur when big cumulonimbus clouds come racing in from the sea on to our northern coasts in winter. Thunderstorms tend to be quite frequent in parts of the tropics where deep cumulonimbus clouds are common. 7. Fog The official definition of fog is a visibility of below 1000 metres. This limit is sensible for aviation purposes but for the general public and motorist an upper limit of 200 metres is more realistic. Severe disruption to transport occurs when the visibility falls below 50 metres. Useful labels for these three categories are aviation fog, thick fog and dense fog (see Table 1). The reduction in visibility is due to tiny water droplets suspended in the air. In industrial areas where there are many pollution particles on which the water droplets can grow the thickest fogs tend to occur. Freezing fog is composed of supercooled water droplets (i.e. ones which remain as liquid water even though the temperature is below freezingpoint). One of the characteristics of freezing fog is that rime - composed of feathery crystals of ice - is deposited on the windward side of vertical surfaces such as lamp-posts, fence posts, overhead wires, pylons and transmitting masts. Dense fog Thick fog Aviation fog Mist or haze Severe disruption to most transport Road, rail and aircraft on the ground delayed All aircraft landings affected to some extent Shipping and light aircraft affected Zero 50 m 200 m 1000 m 5000 m Table 1. Difficulties for transport caused by various categories of poor visibility. Away from coasts the most common type of fog is “radiation fog”. It forms overnight when the ground loses heat by radiation and cools. The ground in turn cools the nearby air to saturation point. Liquid water droplets form as continued cooling occurs, but instead of falling out as dew it is held in suspension by light winds in the form of fog. Often the fog remains patchy and is confined to low ground, but sometimes it Page 8 of 10 Last Saved Date: 9 March 2016 File: ms-train-college-work-d:\533580286.doc becomes more dense and widespread through the night. Ideal conditions for the formation of this type of fog are light winds, clear skies and long nights. Consequently the months of November, December and January are inclined to fogginess, particularly the inland areas of England and the lowlands of Scotland in high pressure conditions. After dawn, thin fog tends to disperse because it is “burnt off’ by the incoming solar radiation. Some of the solar radiation penetrates the fog and reaches the ground. The ground heats up, as does the layer of air near the ground. Eventually the air reaches a temperature where the minute fog droplets evaporate and the visibility improves. However, in winter thick fogs can be very persistent due to the lack of insolation. Some coastal regions of the British Isles suffer from “sea fog” which forms when moist air is cooled to saturation point by travelling over a cooler sea. The wind may then take the fog into coastal regions. This type of fog tends to occur in spring and summer and particularly affects coasts in the south-west and the North Sea coasts. Meteorologists often call this “advection fog” because it is blown by the wind. 8. Drizzle and snow grains Drops of drizzle usually fall from a low-level sheet of stratus or stratocumulus. They tend to form by small water droplets in the cloud merging. When the droplets are too heavy to be supported by the updraught in the cloud they fall as drizzle. The mechanism causing the air to rise and to form cloud is turbulence rather than convection, so generally there is a good wind blowing when drizzle occurs. Beneath the clouds the air needs to be moist to prevent any drizzle evaporating before it reaches the ground. Thus “drizzle weather” is associated with very moist air, low cloud (usually with a cloud base less than 800 feet) and probably at least a moderate to fresh breeze. In airmass terminology, drizzle can occur in a tropical maritime airstream, so it is especially likely on south-west facing coasts. An alternative to the turbulence mechanism is uplift over a hill or two, so south-west facing hills tend to be affected by drizzle. Cornwall, Devon, western Wales and north-west Scotland tend to receive more than their share of drizzle. Also in the cold season drizzle sometimes occurs in an easterly airstream coming in from the North Sea or up the Thames estuary. With a typical cloud base of, say, 400 feet and cloud tops at 2,000 feet, subtle changes in the depth of this relatively shallow cloud layer can make a substantial difference to the weather. To put it another way, Page 9 of 10 Last Saved Date: 9 March 2016 File: ms-train-college-work-d:\533580286.doc drizzle is difficult to forecast in detail, particularly in an easterly airstream. The mid-winter equivalents of drizzle are snow grains; these are small compared with snowflakes. Snow grains are often angular in shape and so small that accumulations on the ground are usually negligible. The breeze may well blow an hour’s worth of snow grains into the roadside gutter, but it still does not amount to much. However, an outbreak of light snow grains can turn to “proper” snow. Page 10 of 10 Last Saved Date: 9 March 2016 File: ms-train-college-work-d:\533580286.doc